Team:Calgary/Project/HumanPractices/Killswitch/Regulation

From 2012.igem.org

| (223 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

CONTENT= | CONTENT= | ||

<html> | <html> | ||

| - | < | + | |

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2012/8/8c/UCalgary2012_FRED_Killswitch_Regulation_Low-Res.png" style="float: right; padding: 10px; height: 200px;"></img> | ||

<div align="justify"> | <div align="justify"> | ||

| - | <h2> | + | <h2> Tight Regulation </h2> |

| + | <p>Inducible kill systems are not new to iGEM. Looking through the registry, there are several constructs such as the inducible BamHI system contributed by Berkley in 2007 (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_I716462">BBa_I716462</a>) and <a href="http://partsregistry.org/Image:UoflBamHIdatasheet.png">tested by Lethbridge in 2011</a>. This uses a <i>BamHI</i> gene downsteam of an arabinose-inducible promoter. Another example is an IPTG inducible Colicin construct (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K117009">BBa_K117009</a>) submitted by NTU-Singapore in 2008. One major problem with these systems however is a lack of tight control. As was demonstrated by the Lethbridge 2011 team, this part has leaky expression when inducer compound is not present. The frequently used lacI promoter has similar problems when not used in conjunction with strong plasmid-mediated expression of lacI. This can be seen in our electrochemical characterization of the UidA hydrolase enzyme (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902002">BBa_K902002</a>) shown here. Tight control is not only a problem for kill switch application, but for any application requiring strict regulation. As such, we decided that expanding the registry repertoire of control elements would be useful for our system as well as a variety of other applications. Therefore we added a new level of regulation in addition to the promoter, a riboswitch.</p> | ||

| + | <h2> Introducing the Riboswitch </h2> | ||

| + | <p>Riboswitches are small pieces of mRNA which bind ligands to modify translation of downstream genes. These sites are engineered into circuits by replacing traditional ribosome binding sites with riboswitches. The riboswitch is able to bind its respective ligand to inhibit or promote binding of translational machinery (Vitreschak <i>et al</i>, 2004). Riboswitches can be used in tandem with an appropriate promoter to enable tighter control of gene expression. Given this opportunity for control, and that ligands for riboswitches are often inexpensive small ions, these methods might be a feasible solution for controlling the kill switch in our industrial bioreactor.</p> | ||

| - | < | + | </html> [[File:UofC_RIBOSWITCH.png|thumb|350px|centre|Figure 1: A simple diagram illustrating the riboswitch and the three metabolite, magnesium, manganese and molybdenum, we have tested.]] <html> |

| - | <p> | + | <p>We explored 3 different riboswitches, each responsive to a different metabolite (magnesium, manganese or molybdate co-factor) that would be inexpensive to implement into a bioreactor environment. Additionally, we also investigated a repressible and inducible promoter, responsive to glucose and rhamnose respectively.</p> |

| + | <p>The general approach taken to build the system was constructing the promoter with the respective riboswitch followed by the kill genes. </p> | ||

| + | <h2>Magnesium riboswitch</h2> | ||

| + | <p>The magnesium riboswitch that we looked at is repressed in the presence of magnesium ions. This system has two control components – a promoter and a riboswitch. Normally the magnesium (mgtA) promoter (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902009">BBa_K902009</a>) and the magnesium (mgtA) riboswitch (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902008">BBa_K902009</a>) are activated if there is a deficiency of magnesium in the cell (Groisman, 2001). The sequence of the <i>mgtA</i> promoter and riboswitch was obtained from Winnie and Groisman. A lack of magnesium activates other genes in <i>E. coli </i>to allow influx of magnesium into the cell. The two proteins in the cascade that activate the system are <i>PhoP</i> (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902010">BBa_K902010</a>) and <i>PhoQ</i> (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902011">BBa_K902011</a>). <i>PhoQ</i> is the trans-membrane protein which gets activated in the absence of magnesium and phosphorylates <i>PhoP</i>. <i>PhoP</i> in turn binds to the mgtA promoter and transcribes genes downstream (Groisman, 2001).</p> | ||

| - | <p> | + | <h2>Manganese riboswitch</h2> |

| + | <p> Manganese is an essential micronutrient. It is an important co-factor for enzymes and it also reduces oxidative stress in the cell (Waters <i>et al</i>. 2011). Despite being an important micronutrient, it is toxic to cells at high levels. MntR protein detects the level of manganese in the cell and acts as a transcription factor to control the expression of manganese transporter such as MntH, MntP and MntABCDE. In order to regulate these genes <i>mntR</i> (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902030">BBa_K902030</a>) binds to the mntP promoter (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902073">BBa_K902073</a>). The manganese homeostasis is also controlled by the manganese riboswitch <i>mntPrb</i> (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902074">BBa_K90274</a>). The sequences of the <i>mntP</i> promoter and the <i>mntP</i> riboswitch was obtained from the Waters et al, 2011.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | [[File:Ucalgary2012 KillswitchstuffsystemsAandB.png|thumb|800px|left|Figure 2: '''A)''' MgtA pathway in <i>E. coli</i>. <i>PhoQ</i> is the transmembrane receptor which, upon detecting low magnesium concentrations, phosphorylates <i>PhoP</i> which acts as a transcription factor, transcribing genes downstream of the MgtA promoter necessary for bringing magnesium into the cell. There is a second level of control with the magnesium riboswitch. In the presence of high magnesium the riboswitch forms a secondary structure which does not allow the ribosome to bind to the transcript, thus inhibiting translation. '''B)''' In the presence of manganese, the <i>MntR</i> protein represses the <i>mntH</i> transporter, preventing the movement of manganese and also upregulating the putative efflux pump. Genes downstream of the mntP promoter are thus transcribed in the presence of manganese. The addition of the <i>MntR</i> protein in this system allows for tighter regulation of the system.]]<html> | ||

| - | + | <h2> The Moco Riboswitch </h2> | |

| - | <h2> | + | |

| - | <p>The | + | <p>The molybdenum cofactor riboswitch (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902023">BBa_K902023</a>) is an RNA element which responds to the presence of the metabolite molybdenum cofactor (MOCO) (Regulski et al, 2008). This RNA element is located in the <i>E.coli</i> genome just upstream of the <i>moaABCDE</i> operon (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902024">BBa_K902024</a>), containing the MOCO synthesis genes. MOCO is an important co-factor in many different enzymes. The MOCO riboswitch has 2 regions: an aptamer domain and the expression platform. When MOCO is present in the cell it will bind to the aptamer region in the riboswitch causing an allosteric change. This allosteric change affects the expression platform by physically hiding the ribosome binding site which prevents translation.</p> |

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | + | </html> | |

| - | < | + | [[File:Moco_riboswitchCalgary2012.jpg|thumb|750px|center|Figure 3: This picture depicts the MOCO RNA motif which is upstream of the <i>moaABCDE</i> operon. ]]<html> |

| - | < | + | <h2> Building the Systems </h2> |

| - | <p>( | + | <p> Using these riboswitches, we wanted to design a system where we would place our kill genes downstream, and then supplement our bioreactor with the appropriate ions to keep the systems turned off. We biobricked and submitted DNA for the the <i>mgtaP</i> (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902009">BBa_K902009</a>) and mntP promoter (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902073">BBa_K902073</a>) as well as their respective riboswitches (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902008">BBa_K902008</a>) (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902074">BBa_K902074</a>) and the MOCO riboswitch (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902023">BBa_K902023</a>). In addition, we also biobricked some of the regulatory proteins: <i>PhoP</i> (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902010">BBa_K902010</a>), <i>PhoQ</i> (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902011">BBa_K902011</a>), <i>mntR</i> (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902030">BBa_K902030</a>) and the Moa Operon (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902024">BBa_K902024</a>). Our final system would inovolve constitutive expression of these necessary regulatory elements upstream of our riboswitches and kill genes. An example of the manganese system is shown in Figure 4. </p> |

| - | < | + | </html>[[File:U.Calgary.2012_10.02.2012_Final_Construct_1.png|thumb|600px|center|Figure 4: Final construct for the manganese system. The circuit includes a TetR promoter, RBS, mntR, double terminator, mntP promoter, mntP riboswitch, <i>S7</i>, mntP riboswitch and <i>CViAII</i>.]]<html> |

| + | |||

| - | < | + | <a name="killswitch"></a><h2> Characterizing the riboswitches </h2> |

| - | < | + | <h3> GFP testing</h3> |

| - | < | + | </html>[[File:MgtA circuits Ucalgary1.png|thumb|150px|right|Figure 5: In these sets of circuits, <i>TetR</i>-RBS-K082003 serves as a positive control and the <i>mgtAp-mgtArb</i> serves as a negative control.]]<html> |

| - | <p> | + | <p> In order to test the control of these promoters and riboswitches, we constructed them independently and together upstream of GFP (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K082003">BBa_K082003</a>) with an LVA tag. Figure 5 shows these circuits for the mgtA system. Identical circuits were designed for all three systems, however only the top two were needed for the MOCO riboswitch system.</p> |

| - | <p> | + | <p>We then tested the aforementioned circuits by growing cells containing our circuits with varying concentrations of their respective ions. Our detailed protocols can be found <a href="https://2012.igem.org/Team:Calgary/Notebook/Protocols/mgcircuit">here</a>. We then measured fluorescent output, normalizing to a negative control not expressing GFP.</p> |

| - | < | + | <h3> Results </h3> |

| - | <p></ | + | <p>So far, we have been able to obtain results for our magnesium system, as can be seen in Figure 6. </html> |

| - | < | + | [[File:Magmesium graph ucalgary2.png|thumb|500px|left|Figure 6: This graph represents the relative fluorescence units from the mgtA promoter riboswitch construct as well as the riboswitch construct under the TetR promoter (BBa_R0040). We can see a decrease in the level of GFP output with increasing concentrations of magnesium. There is much steeper decrease in the GFP output in the construct with the magnesium promoter and riboswitch compared to the construct with just the riboswitch alone.]]<html></p> |

| + | |||

| + | <br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br> | ||

| - | |||

| - | <p> | + | <p>As the graph shows, there is a much larger decrease in the GFP output when the mgtA promoter and riboswitch are working together as compared to the <i>mgtA</i> riboswitch alone under the control of TetR promoter (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_J13002">BBa_J13002</a>). This suggests that having both the promoter and the riboswitch together provides a tighter control over the genes expressed downstream. This also suggests that the magnesium riboswitch alone is sufficient in reducing gene expression downstream of a constitutive promoter.</p> |

| - | <p></ | + | <p> It is important to consider however that the control elements of the system, <a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902010"><i>PhoP</i> </a> and <a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902011"> <i>PhoQ</i></a>, that were described above were not present in the circuits tested and therefore there is GFP expression in at the inhibitory concentration (10 mM MgCl<sub>2</sub>). We believe that having the regulatory elements would give us better control and limit the leakiness.</p> |

| - | < | + | |

| - | <p> | + | <p>Although the magnesium system is highly regulated, it is not a suitable system for the purposes of our bioreactor. The tailings are composed of very high concentration of magnesium, as high as 120 mM (Kim <i>et al</i>. 2011). As can be seen, this would inhibit the system. Therefore, if our bacteria were to escape into the tailings, the kill genes would not be activated and the bacteria would be able to survive. However, we feel that this could still be an incredibly useful system for other teams for both killswitch and non-killswitch-related applications, making it still a valuable contribution to the registry. </p> |

| + | <h3> Kill Gene Testing </h3> | ||

| + | <p> While building our systems with GFP in order to test their control, we also constructed them with our kill genes. This was delayed substantially however due to problems in their synthesis. Specifically, the micrococcal nuclease that arrived from IDT had a 1bp point mutation which changed an isoleucine residue into a lysine. Initially, our systems resulted in no killing of cells. Therefore we had to mutate this residue using <a href="https://2012.igem.org/Team:Calgary/Notebook/Protocols/mutagenesis"> site-directed mutagenesis</a>. Once completed, we were able to begin testing. With our GFP data collected, we moved on to characterizing the mgtA control system upstream of our <i>S7</i> kill gene (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902019">BBa_K902019</a>). To test the circuits, we incubated cells expressing our construct with varying concentrations of magnesium. We then measured both Colony Forming Units (CFU) and OD 600. For a detailed protocol, see <a href="https://2012.igem.org/Team:Calgary/Notebook/Protocols/mgtacircuit">here</a>.</p> | ||

| + | <h3> Results </h3> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </html>[[File: 24 hour assay with mgtap-rb-S7-1.png|thumb|750px|center| Figure 7: This shows the OD600 values of mgtA circuits with S7 both mutated and unmutated. The negative control consists of <i>mgtAp-mgtArb</i>.]]<html> | ||

| + | <p> Figure 7 shows that the mgtAp-mgtArb-S7 (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902018">BBa_K902018</a>) starts acting approximately 4 hours after induction. However, it also shows that 10mM MgCl<sub>2</sub> is not enough salt to inhibit the entire system because there is no difference in OD600 measurement at 4hr time point between 10mM and the 0mM concentrations. This test needs to be repeated with higher concentrations of Mg<sup>2+</sup> however this data suggests that the mutagenesis was successful and <i>S7</i> is active and killing the cells at approximately 4hr which does not necessarily reflect solely upon the activity of <i>S7</i> but also on the response time of the mgtA system.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <h2>An alternative: a glucose repressible system</h2> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Based on the problem with the magnesium system in relation to tailings pond conditions, we wanted to find an alternative. We found a promoter that was induced by rhamnose and repressed by glucose. This seemed to be a very suitable candidate for controlling the kill switch in the bioreactor since the promoter was shown to be tightly repressed by glucose. We could supplement the bioreactor with glucose to inhibit expression of the kill genes in the bioreactor. Escape of bacteria into the tailings ponds would cause expression of the kill genes due to lack of glucose in the surrounding environment. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p>This promoter, known as <i>pRha</i> (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902065">BBa_K902065</a>), is responsible for regulating genes related to rhamnose metabolism and contains a separate promoter on its leading and reverse strands (see Figure 8). <i>RhaR</i> (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902069">BBa_K902069</a>) and <i>RhaS</i> (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902068">BBa_K902068</a>) serve to regulate expression of the rhamnose metabolism operon <i>rhaBAD</i>. The <i>RhaR</i> transcription factor is activated by L-rhamnose to up-regulate expression <i>rhaSR</i> operon. In turn, the resulting <i>RhaS</i> activates the <i>rhaBAD</i> operon to generate the rhamnose metabolism genes (Egan & Schleif, 1993).</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </html>[[File:NativeRhamnosePromoter_Calgary2012.jpg|thumb|600px|center|Figure 8: The rhamnose metabolism genes as they exist in Top Ten <i>E. coli</i>]] | ||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </html>[[File:PrhaFinal.png|thumb|600px|center|Figure 9: The rhamnose metabolism genes native to <i>E. coli</i>]] | ||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <p>Our kill system is different from the native rhamnose system with the <i>rhaR</i> and <i>rhaS</i> control genes. We have constitutively expressed <i>RhaS</i> to overcome dependency on rhamnose to cause activation of the kill switch. While <i>RhaS</i> is continuously present, the system is shut off in the presence of glucose. However, in the outside environment glucose levels are lower such that <i>RhaS</i> is able to activate the kill genes.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <a name="Prha_results"></a> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>Building the system</h3> | ||

| + | <p>Our team had <i>pRha</i> promoter (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902065">BBa_K902065</a>) commercially synthesized as per the sequence given by Jeske and Altenbuchner (2010). The <i>rhaS</i> (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902068">BBa_K902068</a>) and <i>rhaR</i> (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K902069">BBa_K902069</a>) genes were amplified via PCR from Top 10 <i>E. coli</i> using Kapa HiFi polymerase. </p> | ||

| + | <p>We tested the unoptimized rhamnose system using a fluorescent output. </html> [[File:Calgary_RhaGFPFinal.png|thumb|600px|centre|Figure 10: This has Prha-RBS-GFP that was incubated under different conditions. We can see a large increase with 0.2% rhamnose, 0.5% rhamnose whereas there is no GFP expression in the cells incubated with glucose.]] <html> </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p> Figure 10 shows that the rhamnose system works as expected. The system is turned off with 0.2% glucose whereas GFP is significantly upregulated with 0.2% rhamnose and even more with 0.5% rhamnose. In this system we do not have the RhaS constitutively expressed and therefore GFP may not be expressed in the the control without either glucose or rhamnose. But, we are currently working on building this circuit and will be characterizing the RhaS with Prha and Prha by itself using GFP as a reporter. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p>Additionally, we also tested the rhamnose system with micrococcal nuclease in the presence of glucose and rhamnose in both Top10 cells as well as glyA knockout from the Keio knockout collection on the <a href="https://2012.igem.org/Team:Calgary/Project/Synergy">Synergy Page</a> to compare the GlyA knockout alone, GlyA knockout with killswitch, Top10 with killswitch. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p> | ||

| + | <h2> The Glycine Auxotroph </h2> | ||

| + | <p> The idea of using an auxotropic system was initially considered, however due to the pricing of this system we felt it to be inappropriate for a large scale bioreactor. Auxotrophic systems that we had looked into included the 5-fluoro-orotic acid and histidine, which were both found to be expensive. This idea was reconsidered when our <a href="https://2012.igem.org/Team:Calgary/Project/OSCAR/FluxAnalysis">Flux Variability Analysis</a> showed that the Petrobrick system can be optimized with glycine added to the media. The production of hydrocarbons increased by a factor of 3 with our glycine media when compared to Washington’s production media. This finding justified our introduction of a glycine auxotrophic system as the increased efficiency of the Petrobrick in addition to another safety feature far outweighed the cost of implementing the system. This is feasible because glycine is not readily found in the environment and is relatively inexpensive to supplement on a large scale. </p> <p> We used a knockout strain JW2535-1 from the Keio collection in which the gene responsible for the synthesis of glycine was knocked out. The bacteria become dependent on glycine in the environment. The JW2535-1 knockout strain used works directly on glyA which is a component of the glycine hydroxymethyltransferase by mutating the glyA into Kan which overall prevents the bacteria’s growth. A glycine assay was set up to determine concentrations of glycine needed for the survival of the bacteria. The bacteria were grown on minimal media plate with glycine concentrations ranging from 1 nM to 100 mM. When zero glycine was added to the media there was some bacterial growth over time. This system will therefore need to work in conjunction with the kill switch system as another layer of security to reduce possibility of escapers. Please see our <a href="https://2012.igem.org/Team:Calgary/Project/Synergy">Synergy Page</a> for more information. </p> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

}} | }} | ||

Latest revision as of 04:23, 17 December 2012

Hello! iGEM Calgary's wiki functions best with Javascript enabled, especially for mobile devices. We recommend that you enable Javascript on your device for the best wiki-viewing experience. Thanks!

Regulation/Expression Platform

Tight Regulation

Inducible kill systems are not new to iGEM. Looking through the registry, there are several constructs such as the inducible BamHI system contributed by Berkley in 2007 (BBa_I716462) and tested by Lethbridge in 2011. This uses a BamHI gene downsteam of an arabinose-inducible promoter. Another example is an IPTG inducible Colicin construct (BBa_K117009) submitted by NTU-Singapore in 2008. One major problem with these systems however is a lack of tight control. As was demonstrated by the Lethbridge 2011 team, this part has leaky expression when inducer compound is not present. The frequently used lacI promoter has similar problems when not used in conjunction with strong plasmid-mediated expression of lacI. This can be seen in our electrochemical characterization of the UidA hydrolase enzyme (BBa_K902002) shown here. Tight control is not only a problem for kill switch application, but for any application requiring strict regulation. As such, we decided that expanding the registry repertoire of control elements would be useful for our system as well as a variety of other applications. Therefore we added a new level of regulation in addition to the promoter, a riboswitch.

Introducing the Riboswitch

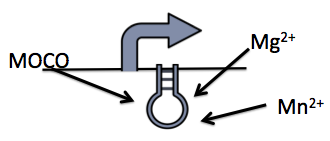

Riboswitches are small pieces of mRNA which bind ligands to modify translation of downstream genes. These sites are engineered into circuits by replacing traditional ribosome binding sites with riboswitches. The riboswitch is able to bind its respective ligand to inhibit or promote binding of translational machinery (Vitreschak et al, 2004). Riboswitches can be used in tandem with an appropriate promoter to enable tighter control of gene expression. Given this opportunity for control, and that ligands for riboswitches are often inexpensive small ions, these methods might be a feasible solution for controlling the kill switch in our industrial bioreactor.

We explored 3 different riboswitches, each responsive to a different metabolite (magnesium, manganese or molybdate co-factor) that would be inexpensive to implement into a bioreactor environment. Additionally, we also investigated a repressible and inducible promoter, responsive to glucose and rhamnose respectively.

The general approach taken to build the system was constructing the promoter with the respective riboswitch followed by the kill genes.

Magnesium riboswitch

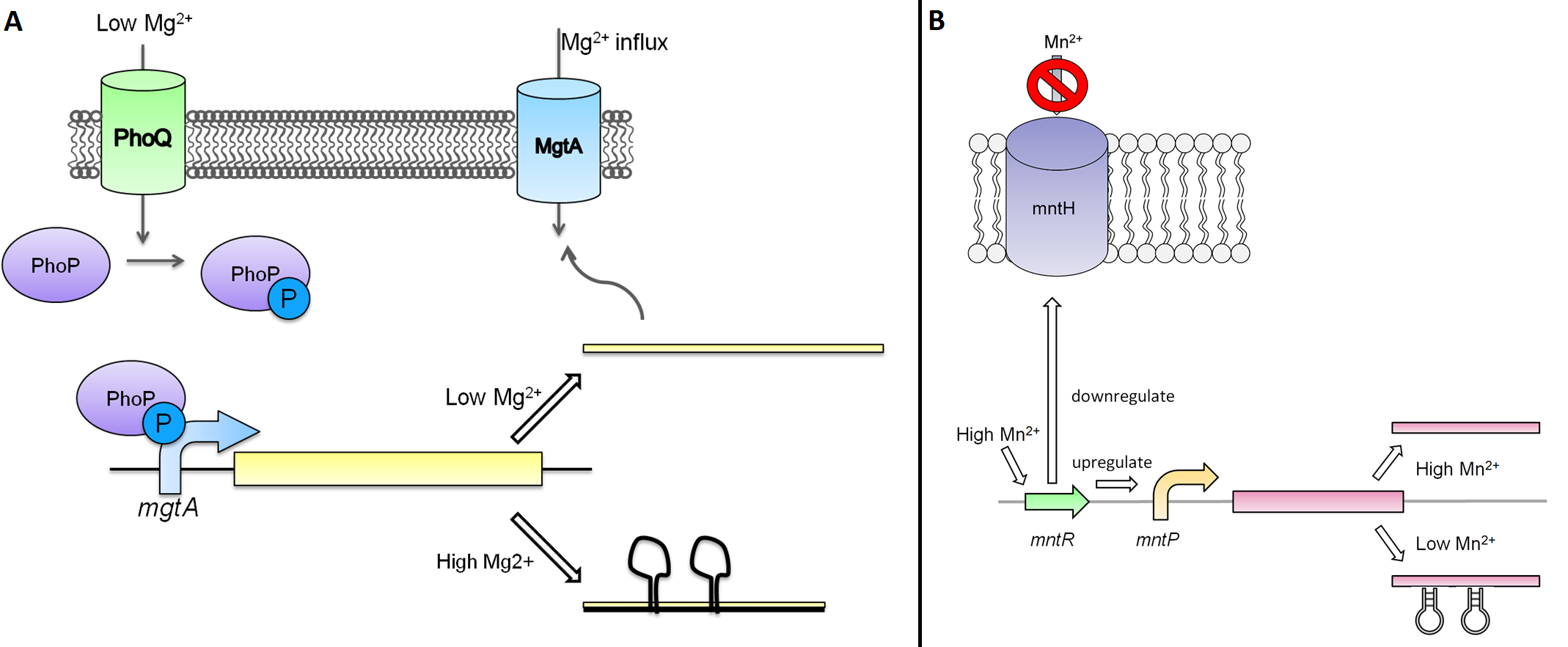

The magnesium riboswitch that we looked at is repressed in the presence of magnesium ions. This system has two control components – a promoter and a riboswitch. Normally the magnesium (mgtA) promoter (BBa_K902009) and the magnesium (mgtA) riboswitch (BBa_K902009) are activated if there is a deficiency of magnesium in the cell (Groisman, 2001). The sequence of the mgtA promoter and riboswitch was obtained from Winnie and Groisman. A lack of magnesium activates other genes in E. coli to allow influx of magnesium into the cell. The two proteins in the cascade that activate the system are PhoP (BBa_K902010) and PhoQ (BBa_K902011). PhoQ is the trans-membrane protein which gets activated in the absence of magnesium and phosphorylates PhoP. PhoP in turn binds to the mgtA promoter and transcribes genes downstream (Groisman, 2001).

Manganese riboswitch

Manganese is an essential micronutrient. It is an important co-factor for enzymes and it also reduces oxidative stress in the cell (Waters et al. 2011). Despite being an important micronutrient, it is toxic to cells at high levels. MntR protein detects the level of manganese in the cell and acts as a transcription factor to control the expression of manganese transporter such as MntH, MntP and MntABCDE. In order to regulate these genes mntR (BBa_K902030) binds to the mntP promoter (BBa_K902073). The manganese homeostasis is also controlled by the manganese riboswitch mntPrb (BBa_K90274). The sequences of the mntP promoter and the mntP riboswitch was obtained from the Waters et al, 2011.

The Moco Riboswitch

The molybdenum cofactor riboswitch (BBa_K902023) is an RNA element which responds to the presence of the metabolite molybdenum cofactor (MOCO) (Regulski et al, 2008). This RNA element is located in the E.coli genome just upstream of the moaABCDE operon (BBa_K902024), containing the MOCO synthesis genes. MOCO is an important co-factor in many different enzymes. The MOCO riboswitch has 2 regions: an aptamer domain and the expression platform. When MOCO is present in the cell it will bind to the aptamer region in the riboswitch causing an allosteric change. This allosteric change affects the expression platform by physically hiding the ribosome binding site which prevents translation.

Building the Systems

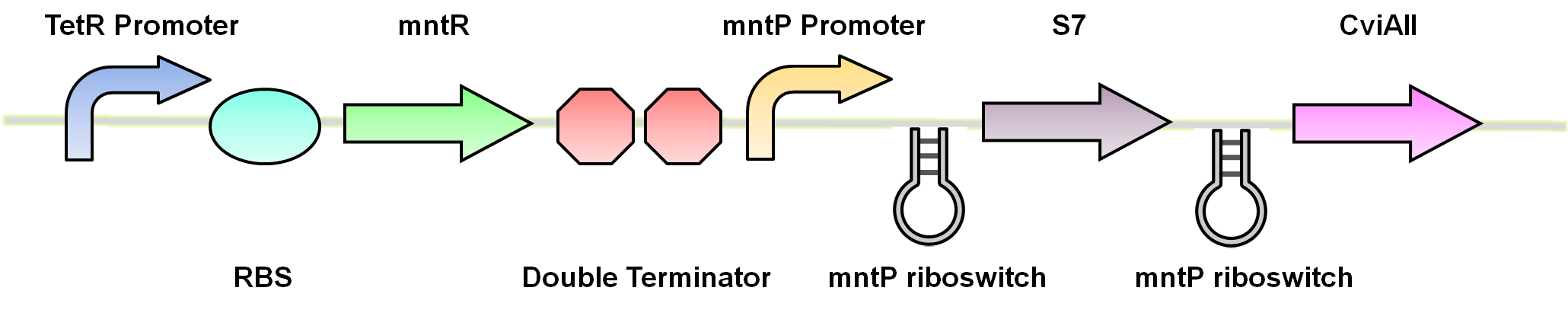

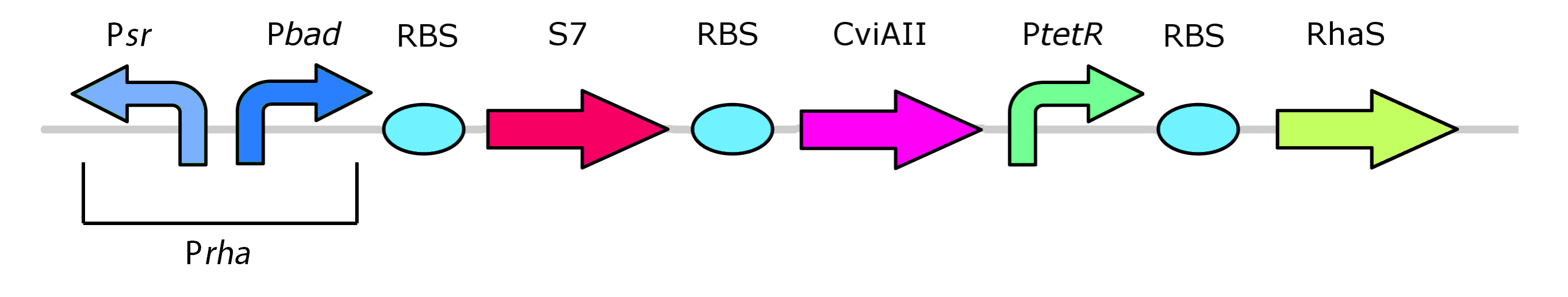

Using these riboswitches, we wanted to design a system where we would place our kill genes downstream, and then supplement our bioreactor with the appropriate ions to keep the systems turned off. We biobricked and submitted DNA for the the mgtaP (BBa_K902009) and mntP promoter (BBa_K902073) as well as their respective riboswitches (BBa_K902008) (BBa_K902074) and the MOCO riboswitch (BBa_K902023). In addition, we also biobricked some of the regulatory proteins: PhoP (BBa_K902010), PhoQ (BBa_K902011), mntR (BBa_K902030) and the Moa Operon (BBa_K902024). Our final system would inovolve constitutive expression of these necessary regulatory elements upstream of our riboswitches and kill genes. An example of the manganese system is shown in Figure 4.

Characterizing the riboswitches

GFP testing

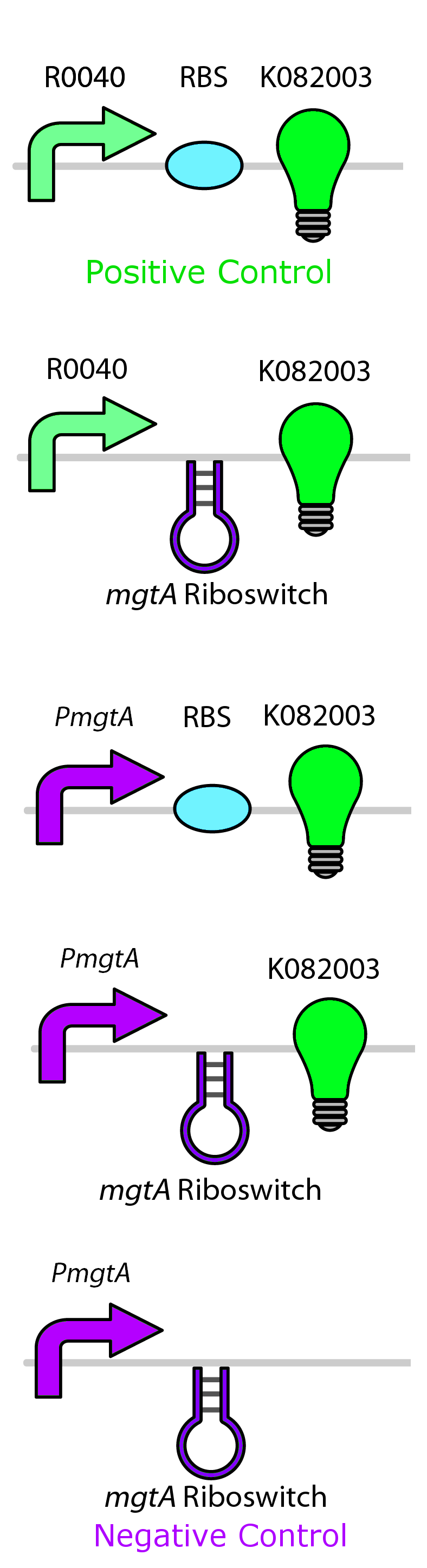

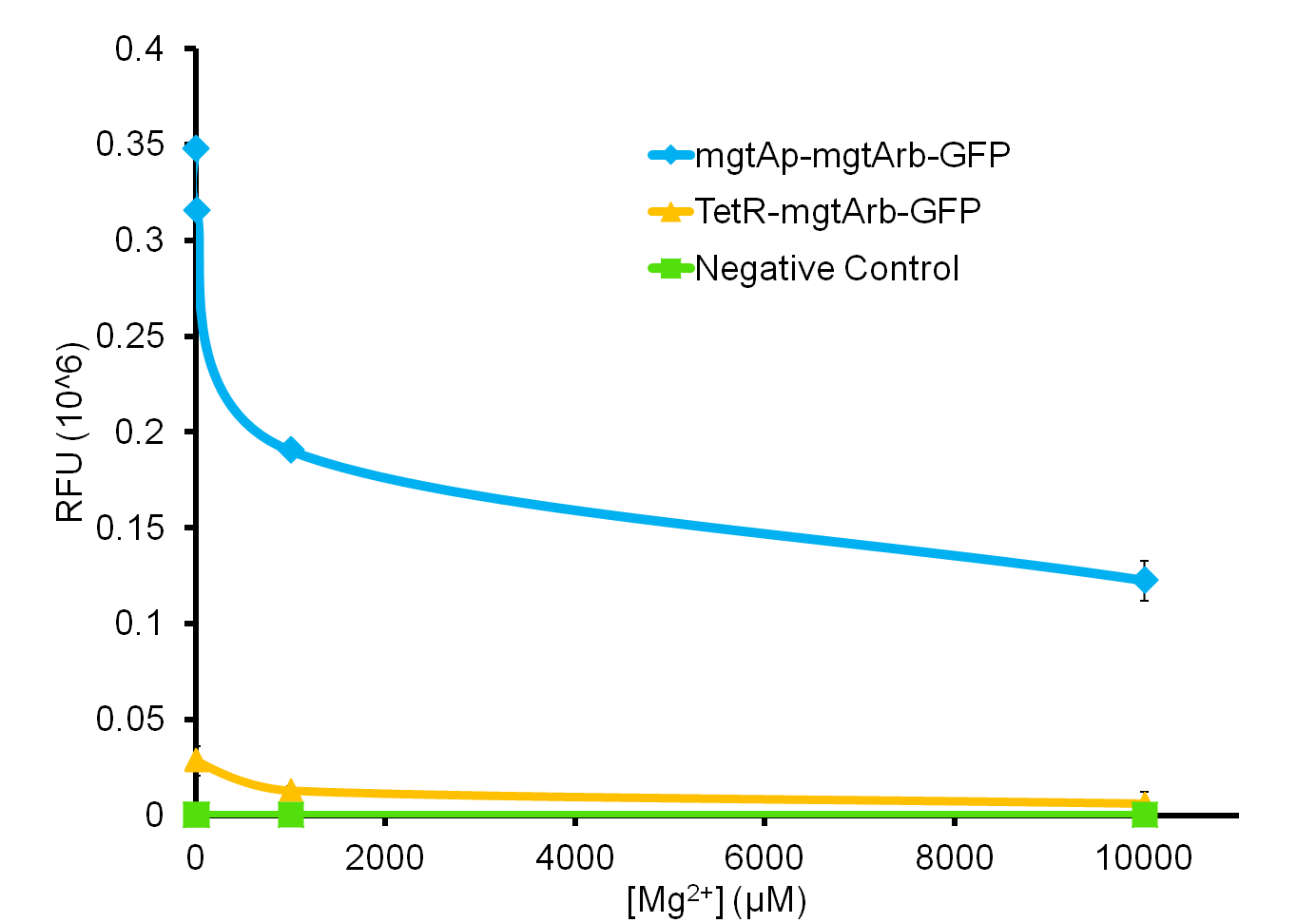

In order to test the control of these promoters and riboswitches, we constructed them independently and together upstream of GFP (BBa_K082003) with an LVA tag. Figure 5 shows these circuits for the mgtA system. Identical circuits were designed for all three systems, however only the top two were needed for the MOCO riboswitch system.

We then tested the aforementioned circuits by growing cells containing our circuits with varying concentrations of their respective ions. Our detailed protocols can be found here. We then measured fluorescent output, normalizing to a negative control not expressing GFP.

Results

So far, we have been able to obtain results for our magnesium system, as can be seen in Figure 6.

As the graph shows, there is a much larger decrease in the GFP output when the mgtA promoter and riboswitch are working together as compared to the mgtA riboswitch alone under the control of TetR promoter (BBa_J13002). This suggests that having both the promoter and the riboswitch together provides a tighter control over the genes expressed downstream. This also suggests that the magnesium riboswitch alone is sufficient in reducing gene expression downstream of a constitutive promoter.

It is important to consider however that the control elements of the system, PhoP and PhoQ, that were described above were not present in the circuits tested and therefore there is GFP expression in at the inhibitory concentration (10 mM MgCl2). We believe that having the regulatory elements would give us better control and limit the leakiness.

Although the magnesium system is highly regulated, it is not a suitable system for the purposes of our bioreactor. The tailings are composed of very high concentration of magnesium, as high as 120 mM (Kim et al. 2011). As can be seen, this would inhibit the system. Therefore, if our bacteria were to escape into the tailings, the kill genes would not be activated and the bacteria would be able to survive. However, we feel that this could still be an incredibly useful system for other teams for both killswitch and non-killswitch-related applications, making it still a valuable contribution to the registry.

Kill Gene Testing

While building our systems with GFP in order to test their control, we also constructed them with our kill genes. This was delayed substantially however due to problems in their synthesis. Specifically, the micrococcal nuclease that arrived from IDT had a 1bp point mutation which changed an isoleucine residue into a lysine. Initially, our systems resulted in no killing of cells. Therefore we had to mutate this residue using site-directed mutagenesis. Once completed, we were able to begin testing. With our GFP data collected, we moved on to characterizing the mgtA control system upstream of our S7 kill gene (BBa_K902019). To test the circuits, we incubated cells expressing our construct with varying concentrations of magnesium. We then measured both Colony Forming Units (CFU) and OD 600. For a detailed protocol, see here.

Results

Figure 7 shows that the mgtAp-mgtArb-S7 (BBa_K902018) starts acting approximately 4 hours after induction. However, it also shows that 10mM MgCl2 is not enough salt to inhibit the entire system because there is no difference in OD600 measurement at 4hr time point between 10mM and the 0mM concentrations. This test needs to be repeated with higher concentrations of Mg2+ however this data suggests that the mutagenesis was successful and S7 is active and killing the cells at approximately 4hr which does not necessarily reflect solely upon the activity of S7 but also on the response time of the mgtA system.

An alternative: a glucose repressible system

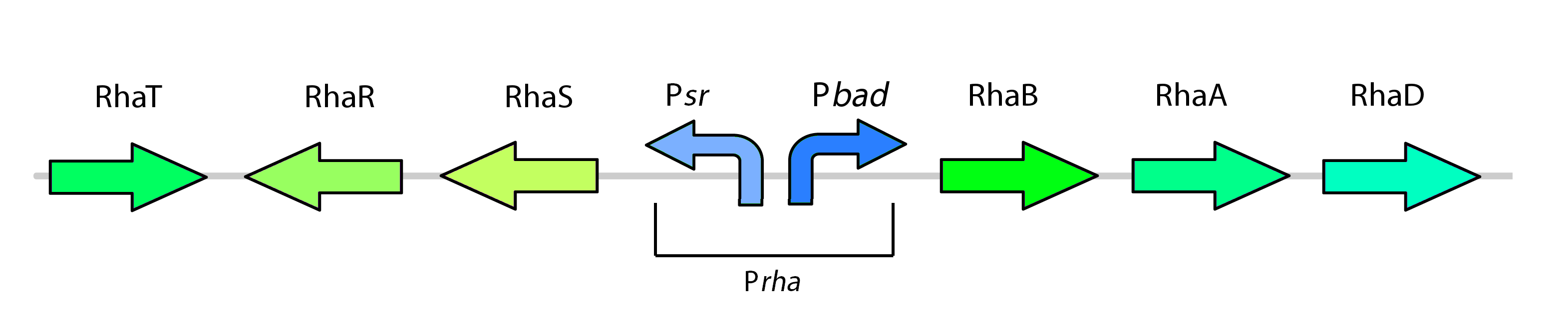

Based on the problem with the magnesium system in relation to tailings pond conditions, we wanted to find an alternative. We found a promoter that was induced by rhamnose and repressed by glucose. This seemed to be a very suitable candidate for controlling the kill switch in the bioreactor since the promoter was shown to be tightly repressed by glucose. We could supplement the bioreactor with glucose to inhibit expression of the kill genes in the bioreactor. Escape of bacteria into the tailings ponds would cause expression of the kill genes due to lack of glucose in the surrounding environment.

This promoter, known as pRha (BBa_K902065), is responsible for regulating genes related to rhamnose metabolism and contains a separate promoter on its leading and reverse strands (see Figure 8). RhaR (BBa_K902069) and RhaS (BBa_K902068) serve to regulate expression of the rhamnose metabolism operon rhaBAD. The RhaR transcription factor is activated by L-rhamnose to up-regulate expression rhaSR operon. In turn, the resulting RhaS activates the rhaBAD operon to generate the rhamnose metabolism genes (Egan & Schleif, 1993).

Our kill system is different from the native rhamnose system with the rhaR and rhaS control genes. We have constitutively expressed RhaS to overcome dependency on rhamnose to cause activation of the kill switch. While RhaS is continuously present, the system is shut off in the presence of glucose. However, in the outside environment glucose levels are lower such that RhaS is able to activate the kill genes.

Building the system

Our team had pRha promoter (BBa_K902065) commercially synthesized as per the sequence given by Jeske and Altenbuchner (2010). The rhaS (BBa_K902068) and rhaR (BBa_K902069) genes were amplified via PCR from Top 10 E. coli using Kapa HiFi polymerase.

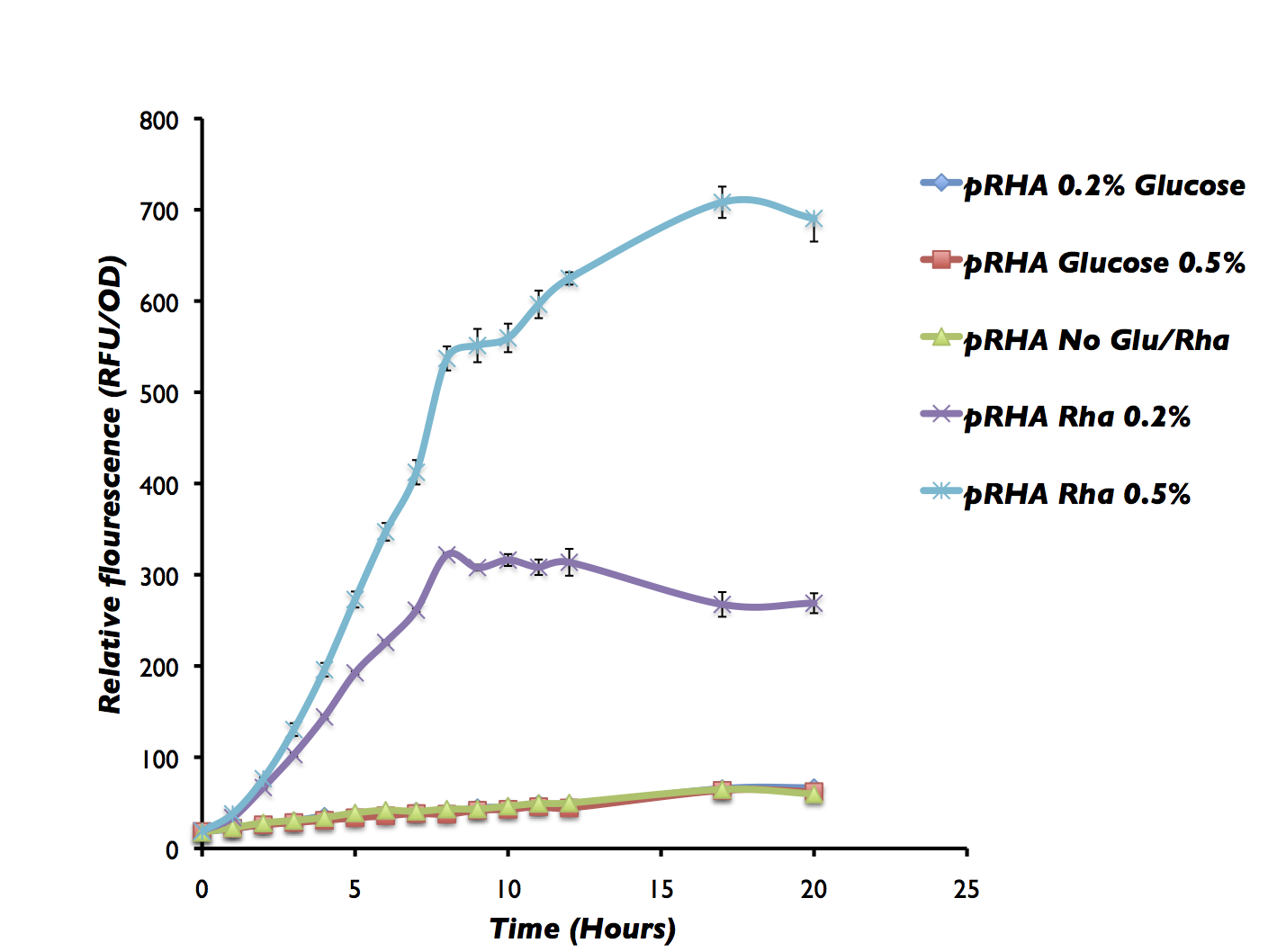

We tested the unoptimized rhamnose system using a fluorescent output.

Figure 10 shows that the rhamnose system works as expected. The system is turned off with 0.2% glucose whereas GFP is significantly upregulated with 0.2% rhamnose and even more with 0.5% rhamnose. In this system we do not have the RhaS constitutively expressed and therefore GFP may not be expressed in the the control without either glucose or rhamnose. But, we are currently working on building this circuit and will be characterizing the RhaS with Prha and Prha by itself using GFP as a reporter.

Additionally, we also tested the rhamnose system with micrococcal nuclease in the presence of glucose and rhamnose in both Top10 cells as well as glyA knockout from the Keio knockout collection on the Synergy Page to compare the GlyA knockout alone, GlyA knockout with killswitch, Top10 with killswitch.

The Glycine Auxotroph

The idea of using an auxotropic system was initially considered, however due to the pricing of this system we felt it to be inappropriate for a large scale bioreactor. Auxotrophic systems that we had looked into included the 5-fluoro-orotic acid and histidine, which were both found to be expensive. This idea was reconsidered when our Flux Variability Analysis showed that the Petrobrick system can be optimized with glycine added to the media. The production of hydrocarbons increased by a factor of 3 with our glycine media when compared to Washington’s production media. This finding justified our introduction of a glycine auxotrophic system as the increased efficiency of the Petrobrick in addition to another safety feature far outweighed the cost of implementing the system. This is feasible because glycine is not readily found in the environment and is relatively inexpensive to supplement on a large scale.

We used a knockout strain JW2535-1 from the Keio collection in which the gene responsible for the synthesis of glycine was knocked out. The bacteria become dependent on glycine in the environment. The JW2535-1 knockout strain used works directly on glyA which is a component of the glycine hydroxymethyltransferase by mutating the glyA into Kan which overall prevents the bacteria’s growth. A glycine assay was set up to determine concentrations of glycine needed for the survival of the bacteria. The bacteria were grown on minimal media plate with glycine concentrations ranging from 1 nM to 100 mM. When zero glycine was added to the media there was some bacterial growth over time. This system will therefore need to work in conjunction with the kill switch system as another layer of security to reduce possibility of escapers. Please see our Synergy Page for more information.

"

"