Team:Calgary/Project/OSCAR/Decarboxylation

From 2012.igem.org

Hello! iGEM Calgary's wiki functions best with Javascript enabled, especially for mobile devices. We recommend that you enable Javascript on your device for the best wiki-viewing experience. Thanks!

Decarboxylation

Why Decarboxylation?

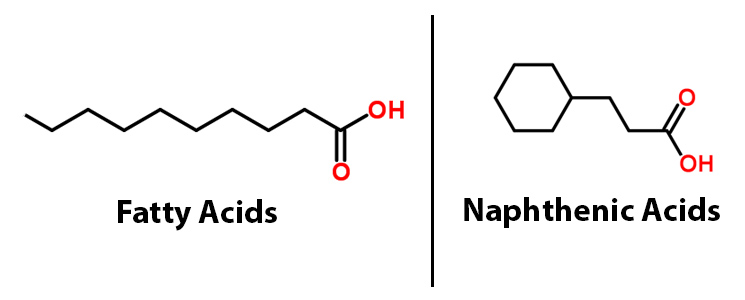

Among the toxins found in the tailing ponds, naphthenic acids (NAs) are among the most harmful and the most common. Though there is great diversity within the NAs class of compounds, all share the common chemical feature of a carboxylic acid group. The carboxyl group is the primary cause for their toxicity, allowing these chemicals to traverse cell membranes and react with cellular materials (Frank et al. 2009). NAs are recalcitrant (not easily degraded), potentially harmful to the surrounding ecosystem (Clemente & Fedorak, 2005) and corrosive to extraction and transport equipment of petroleum materials (Slavcheva et al. 1999). Corrosion of pipelines leads to higher maintenance costs as well as the grim possibility of these and other toxins leaking into the environment. There is a need for methods to degrade NAs that are not prohibitively expensive or that would result in production of other hazardous chemicals.

The main goal of OSCAR is to turn toxins like these into useable hydrocarbons by removing the carboxylic acid group(s) (Behar & Albrecht, 1984). Since NAs from petroleum deposits are a variable mixture, an enzymatic process with broad specificity is necessary. With the removal of the carboxylic acid moiety, we aim to produce alkanes suitable for use as fuel. The goal of this subproject was to find one or more suitable pathways to accomplish the decarboxylation of compounds such as NAs with the broadest specificity.

The PetroBrick

The 2011 Washington iGEM team developed the PetroBrick (BBa_K590025.), a BioBrick consisting of two primary genes. These include acyl-ACP reductase (AAR), which reduces fatty acids bound to ACP to fatty aldehydes, and a second gene called aldehyde decarbonylase (ADC), which subsequently cleaves the entire aldehyde group and results in a hydrocarbon chain (Sukovich, 2010). Essentially this allows for hydrocarbons to be produced from glucose. What we realized though, is that the fatty acids that the PetroBrick targets, have a very similar structure to NAs.

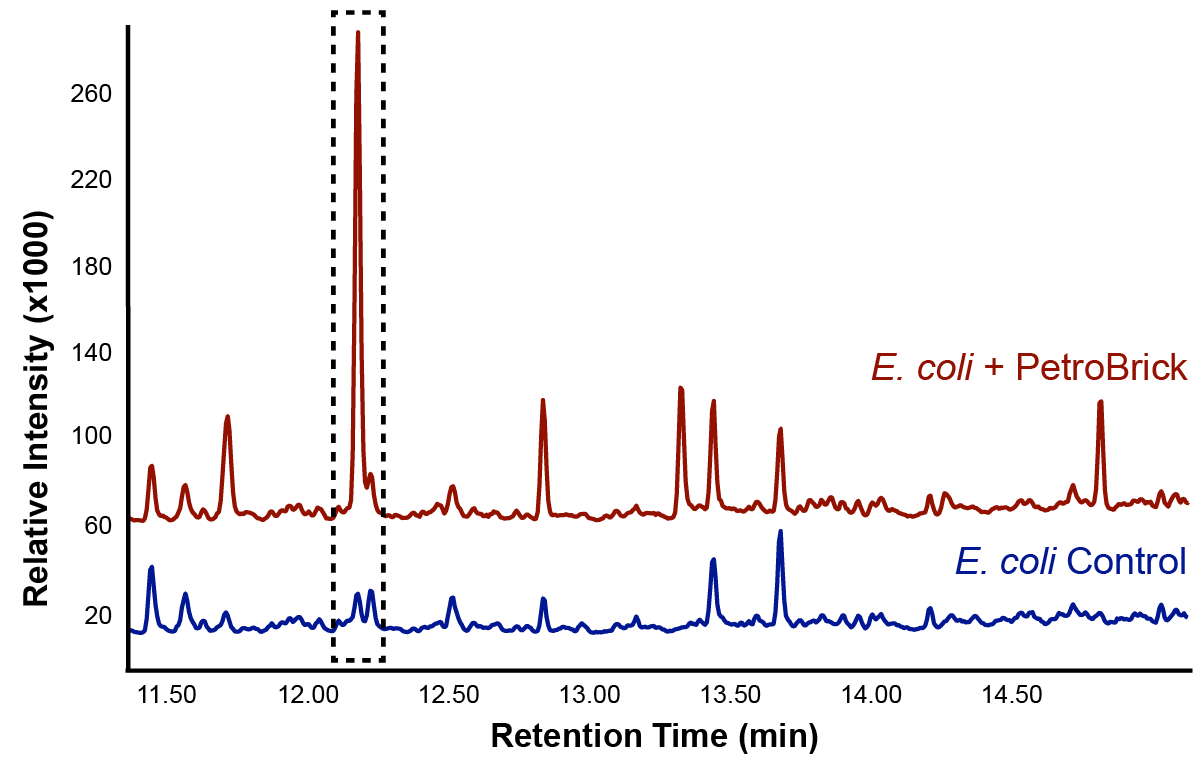

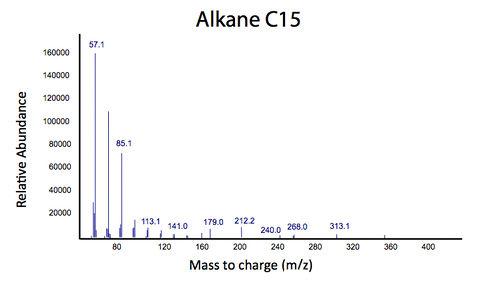

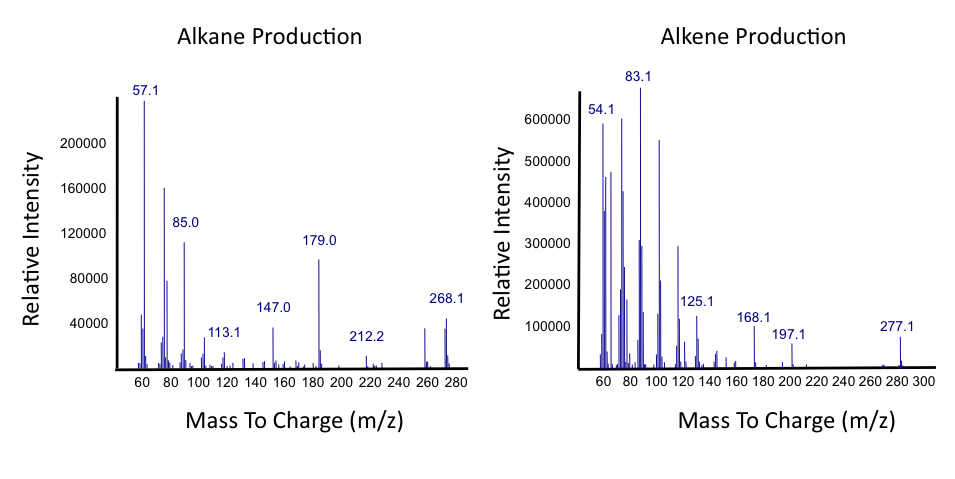

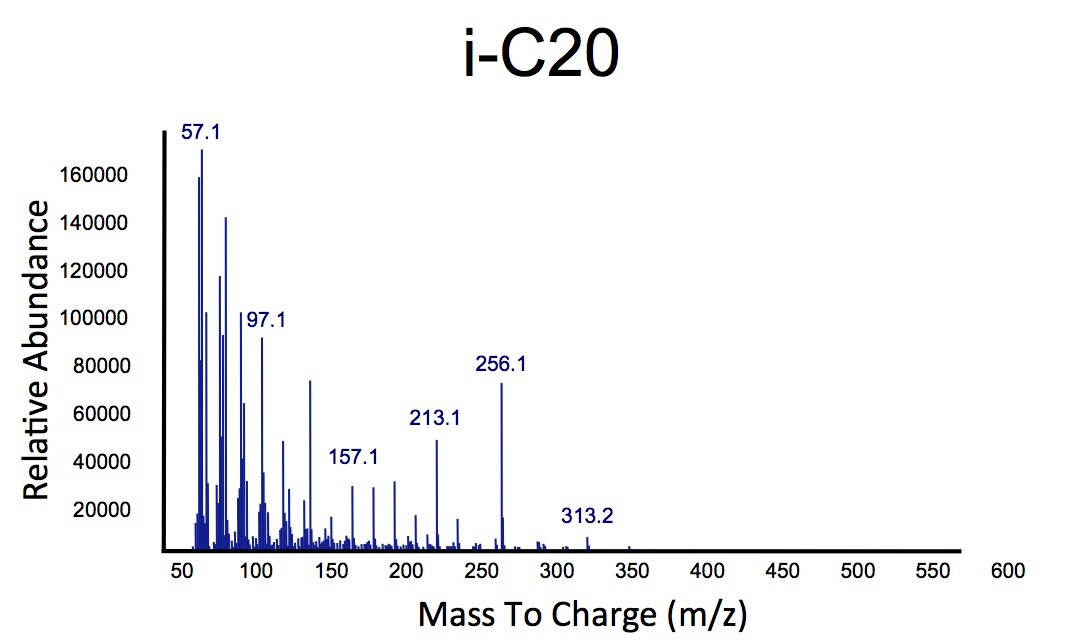

We predicted that the PetroBrick may have the potential to turn NAs in to hydrocarbons and be a perfect solution to remediating NAs! First though, we needed to show that the PetroBrick did in fact work as expected. We had some difficulty with the DNA from the registry and had to request the constructs directly from the Washington team. Once we had the PetroBrick, we needed to verify that the PetroBrick would work in our hands as it did for the 2011 Washington team. Figures 2 and 3 demonstrate the function of the PetroBrick.

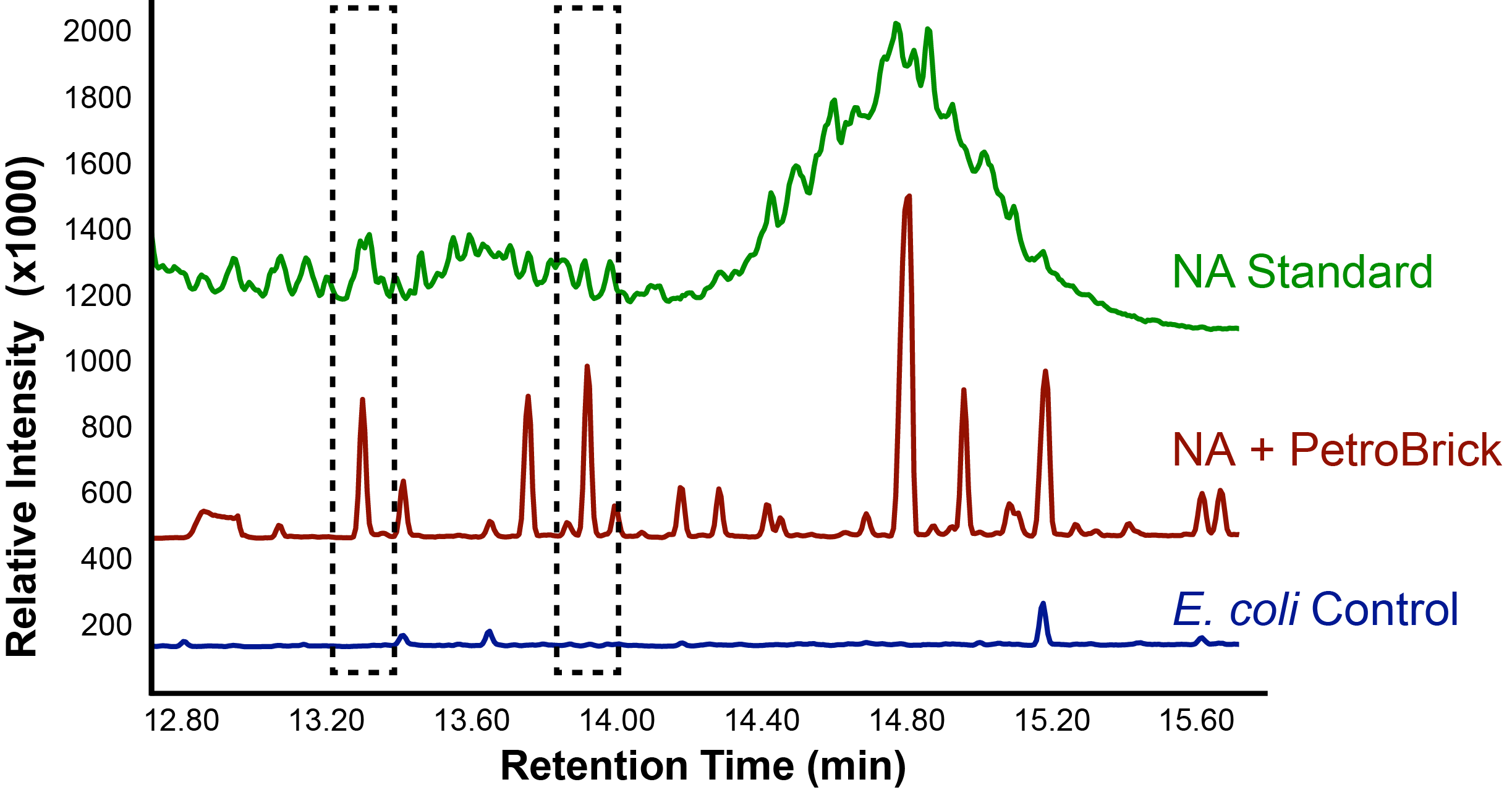

With the PetroBrick able to successfully produce alkanes, we next wanted to test the PetroBrick on NAs to see if they could be selectively converted into alkanes! This experiment used commercial NA fractions, which included a large number of different complex NA compounds.

Successful conversion of NAs into hydrocarbons!

Results from Figure 4 and 5 indicate that hydrocarbons were successfully produced from E. coli that contained the PetroBrick construct, as analysed by GC-MS. In Figure 2, E. coli containing the PetroBrick had larger hydrocarbon peaks than the E. coli without the PetroBrick. Not only was the PetroBrick able to degrade NAs into alkanes, the PetroBrick could produce alkenes (Figure 3), indicating that the PetroBrick worked as expected!

Nocardia Carboxylic Acid Reductase (CAR)- Can we do better?

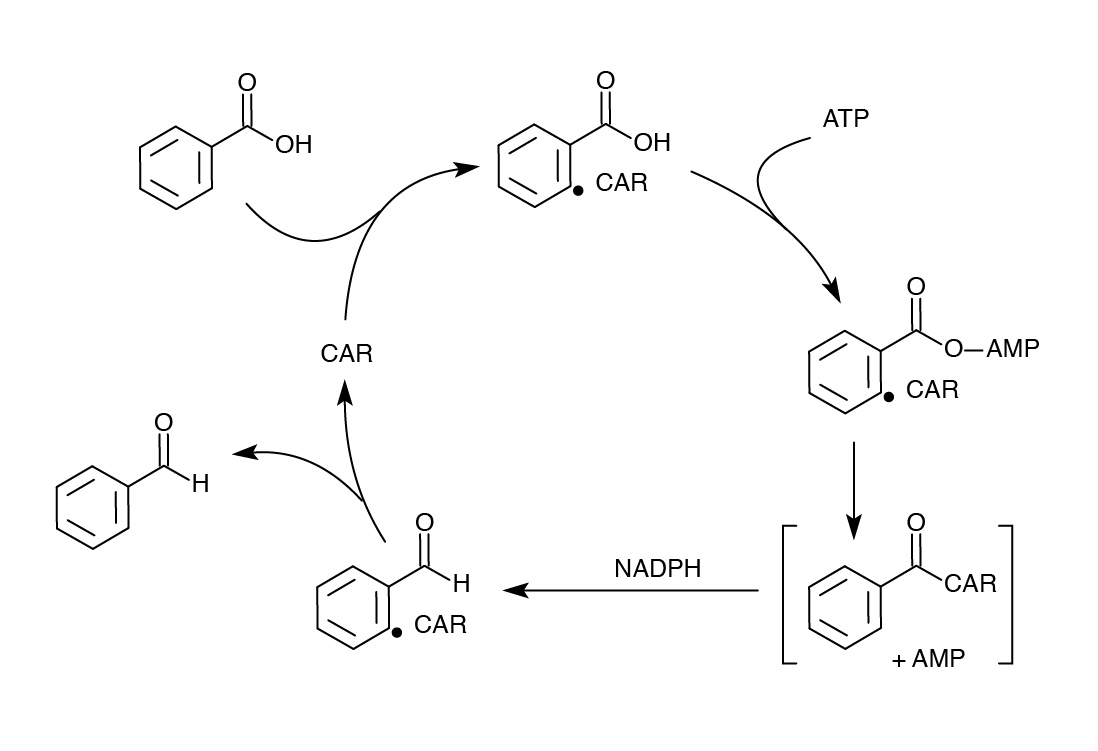

Although we successfully used the PetroBrick to remove carboxyl groups from NAs, we wanted to improve on our results to get a higher yield and/or possibly target other compounds. One of our original concerns in using the PetroBrick to decarboyxlate NAs was that the first enzyme AAR only targeted fatty acids bound to ACP, and non-compatibility with NAs. Therefore, we searched for another enzyme carboxylic acid reductase (CAR) from N. iowensis known to perform a similar task as AAR - converting fatty acids to aldehydes, but with much lower specificity (He et al. 2004). Unlike AAR, CAR does not require covalent attachment to ACP, and likely to have broader substrate specificity. The use of CAR did require a second gene from N. iowensis called Nocardia phosphopantetheinyl transferase (npt) to append a 4’- phosphopantetheine prosthetic group to CAR required for its full function (Venkitasubramanian et al., 2006).

Another enzyme with the potential to remove carboxyl groups from NAs is olefin-forming fatty acid decarboxylase (oleT) from Jeotgalicoccus sp. ATCC 8456. OleT of the cytochrome P450 family acts on fatty acids, but does have low substrate specificity (Rude et al. 2011). Using oleT was beneficial because this single enzyme could do the job of the entire PetroBrick! Given that our decarboxylation approach was valid, we started testing and comparing oleT to the PetroBrick.

Progress so far

Genes car and npt were cloned from the host organism N. iowensis (NRRL 5646). car was ligated into the pET vector and verified by a restriction digest while npt was cloned into pSB1C3 (BBa_K902061) and similarly verified.

car was cloned into pET47b+ plasmid to remove six illegal cut-sites (one XbaI site, two EcoRI sites, and three NotI sites), as it was unsuitable for the BioBrick construction vectors. We first attempted to use a multi-site mutagenesis derived from the QuikChange® Multi-Site Directed Mutagenesis Kit, but had little success. Instead, a more time-consuming but effective series of conventional single-site mutagenesis procedure was used with the KAPA Hi-Fi polymerase. The XbaI and EcoRI sites were eliminated first so that car can be moved from the pET Vector and ligated into the PSB1C3 vector (BBa_K902062).

The oleT was successfully amplified from the Jeotgalicoccus sp. ATCC 8456.

Like car, oleT was inserted in a pET47b+ (Novagen) vector before placing it into a BioBrick vector, as two illegal cut sites adjacent to one another needed to be mutagenized. This part is now being ligated into pSB1C3. We are currently in the process of constructing all three parts under control of a tetR promoter and ribosomal binding site (BBa_J13002), and then constructing these composite parts together as outlined below.

Final testing constructs

Final testing constructs are nearly complete. These are illustrated in Figure 7 and will allow us to compare the three different approaches. Unfortunately, Washington only sent us the PetroBrick and not the two individual components, we will have to compare a combination of the PetroBrick and car/npt to the PetroBrick alone and to oleT.

Testing OleT

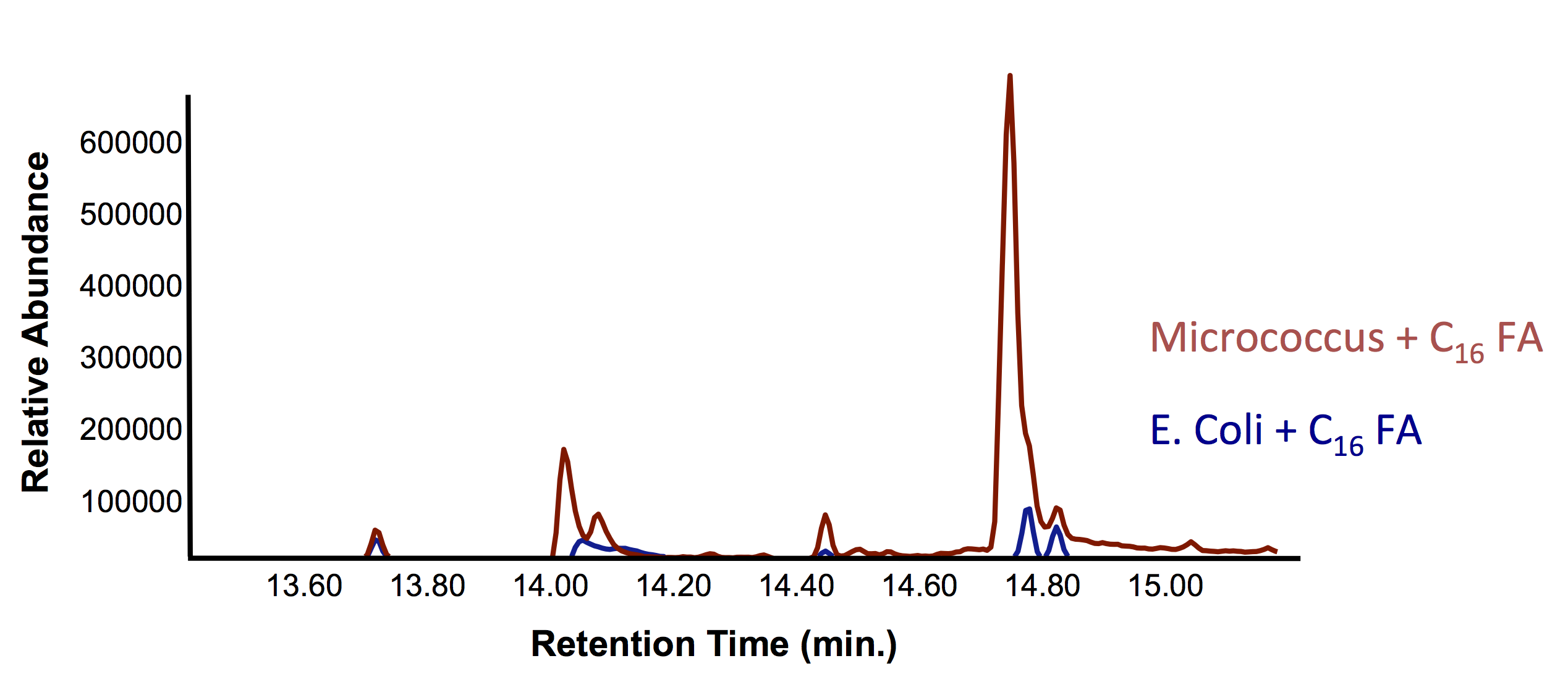

One major stumbling block in testing out oleT is that it has been very difficult to ligate it into a vector, which has prevented us from submitting it as a BioBrick. As such, we chose to try some assays on the host organism: Jeotgalicoccus sp. ATCC 8456. This way we could at least validate that this gene was functional before we had our BioBricks. We started by trying to verify the results by Rude et al., 2011, namely that OleT could convert fatty acids into alkenes. We grew up cultures based on this protocol and used GC-MS to analyze any alkene production (Figure 8 and 9).

Formation of alkanes by Jeotgalicoccus sp. ATCC 8456

Based on the additional peak we saw in the gas chromatograph, we could show that our E. coli can produce alkenes with the oleT. This is may be an improvement over the PetroBrick since OleT is only one enzyme instead of two; however, future testing is still needed. Now that we have validated the function of OleT in producing alkenes, the next step is to test it out on complex naphthenic acids in order to compare it to the PetroBrick. This testing is still underway.

"

"