Team:Valencia Biocampus/Modeling

From 2012.igem.org

Modeling

Mathematical modeling: Introduction

Mathematical modeling plays a central role in Synthetic Biology. One of its mayor abilities: to predict the behavior of a biological circuit. Therefore, it is an important bridge between the ideas and concepts on the one hand, and biological experiments on the other.

The main idea is to interact with the experimental part of the project in two ways. On the one hand to characterize the constructed biobricks, and identify parameters of the models thus allowing to a better understanding of the biology behind. On the other hand, to direct the way in which experiments are performed, so as to verify a prediction done from the modeling world.

The first step, with a little knowledge, was to develop a mathematical model based on a system of differential equations. Then, the equations were implemented using a set of reasonable values, taken from the literature, for the model parameters. This way, we could validate the feasibility of the project. Here, one of the main characters of the play came into the "cheaters". We saw the “cheaters” could appear from an original population of “normal” microorganisms. This lead us to perform several experiments to measure the metabolic burden that arises when cells carrying a synthetic plasmid want to effectively synthetize the desired protein, as compared with cells that are NOT producing the protein. This could lead to increase the fitness of the “cheaters”.

Then we started the characterization of each part created in the lab. Some of the mathematical model parameters were estimated thanks to several experiments we performed within the project (others were derived from literature) and they were used to predict the final behavior of each construction.

Experimental procedures for parameter estimation are discussed and simulation experiments performed, using ODEs with MATLAB and Global optimization algorithm for MINLP's based on Scatter Search (SSm by Process Engineering Group IIM-CSIC).

Modeling Bacteria

Let´s get a closer look to the modeling of our Bacteria constructions.

Are you hungry?

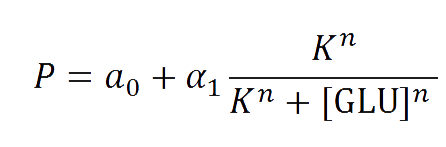

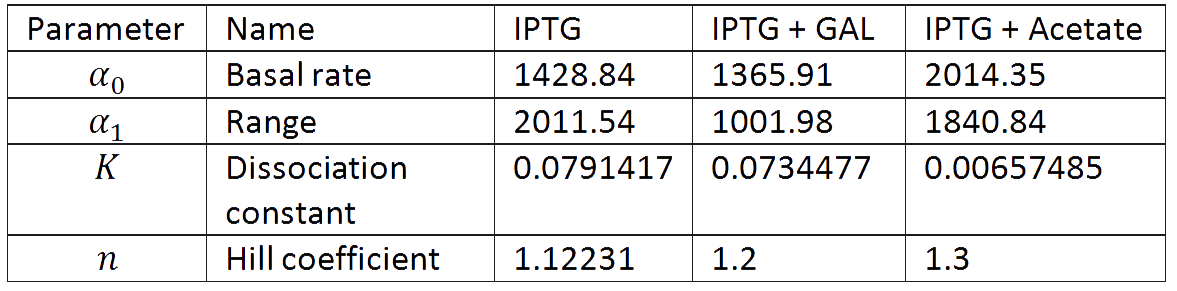

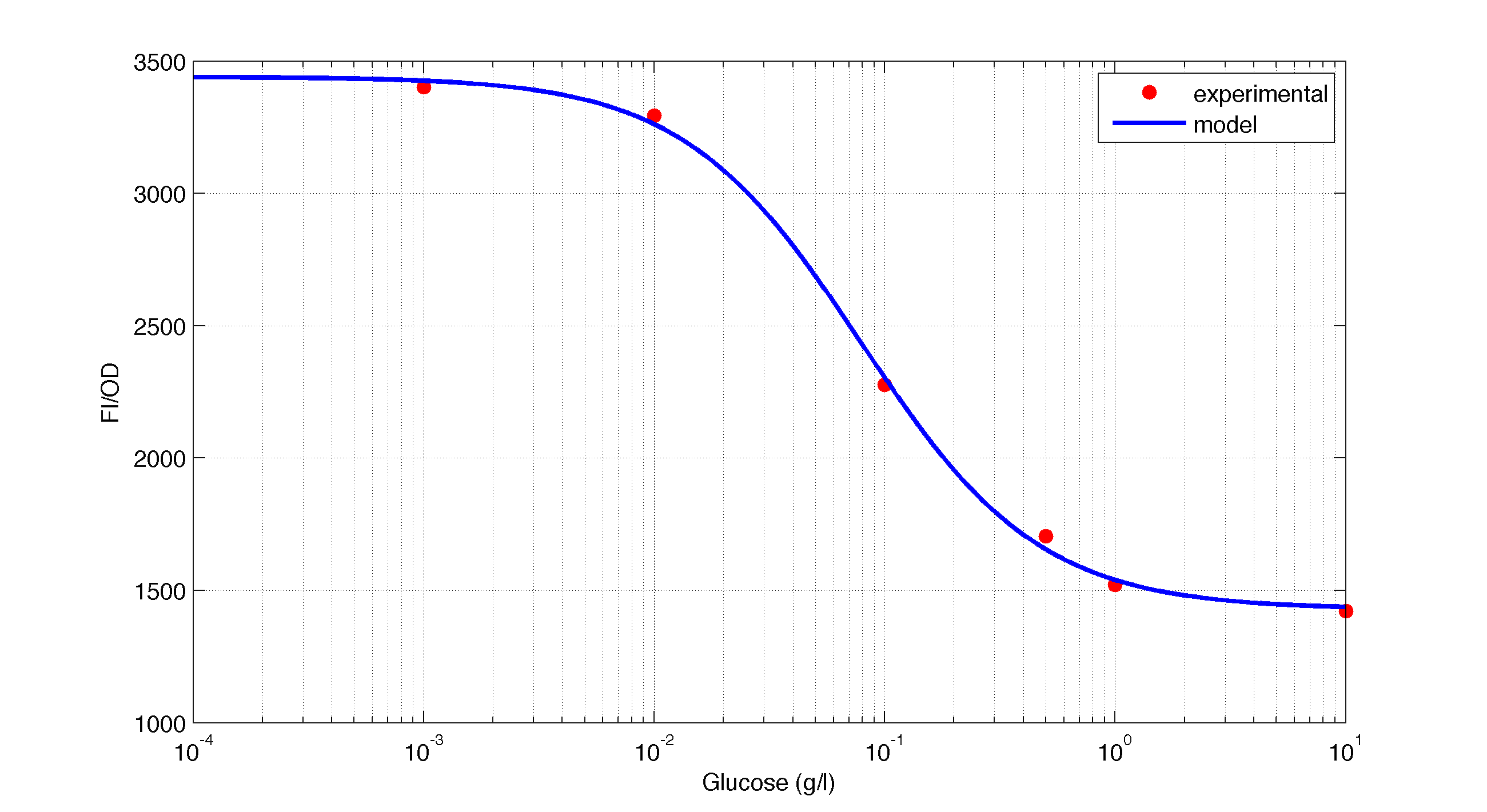

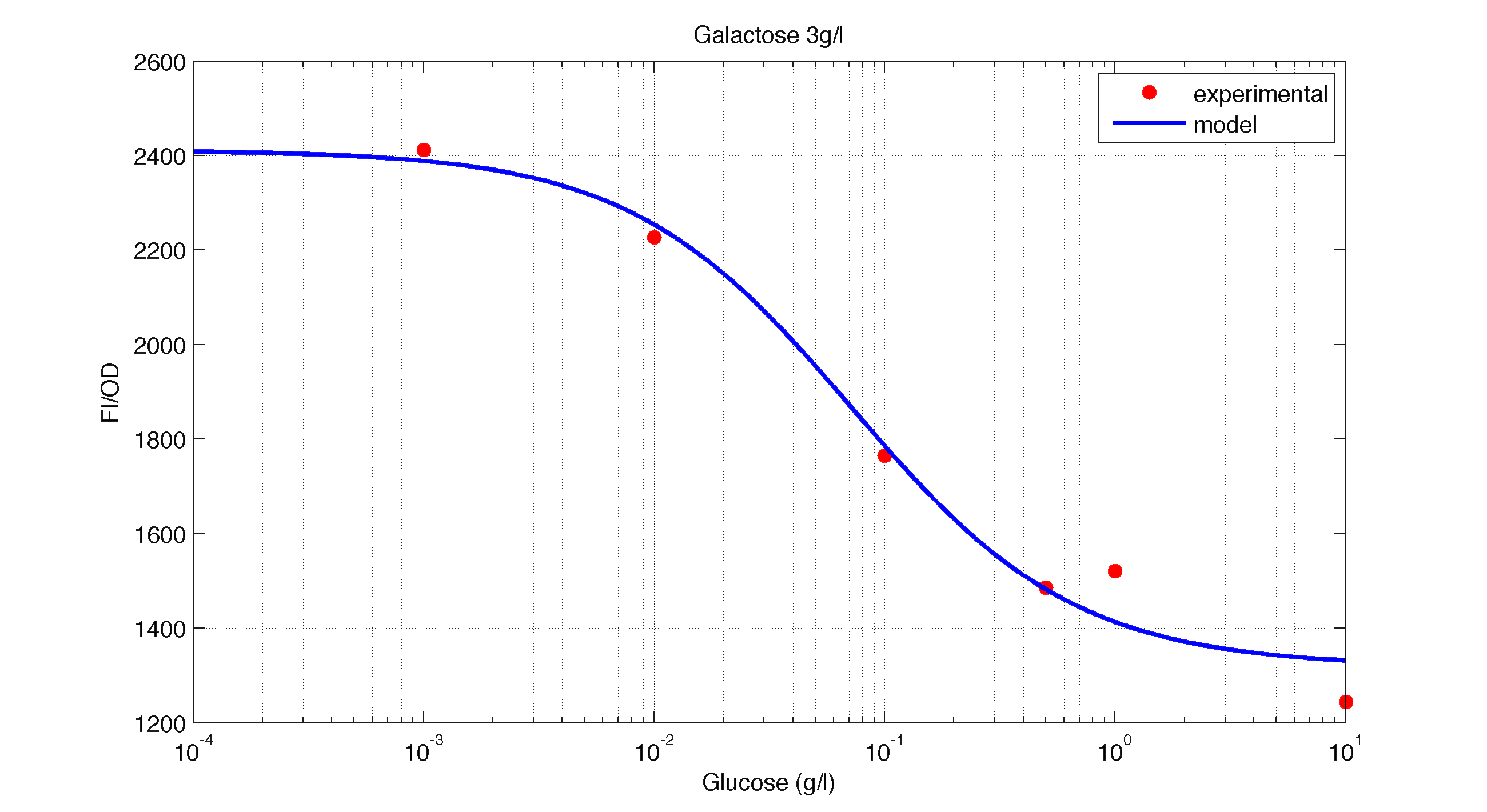

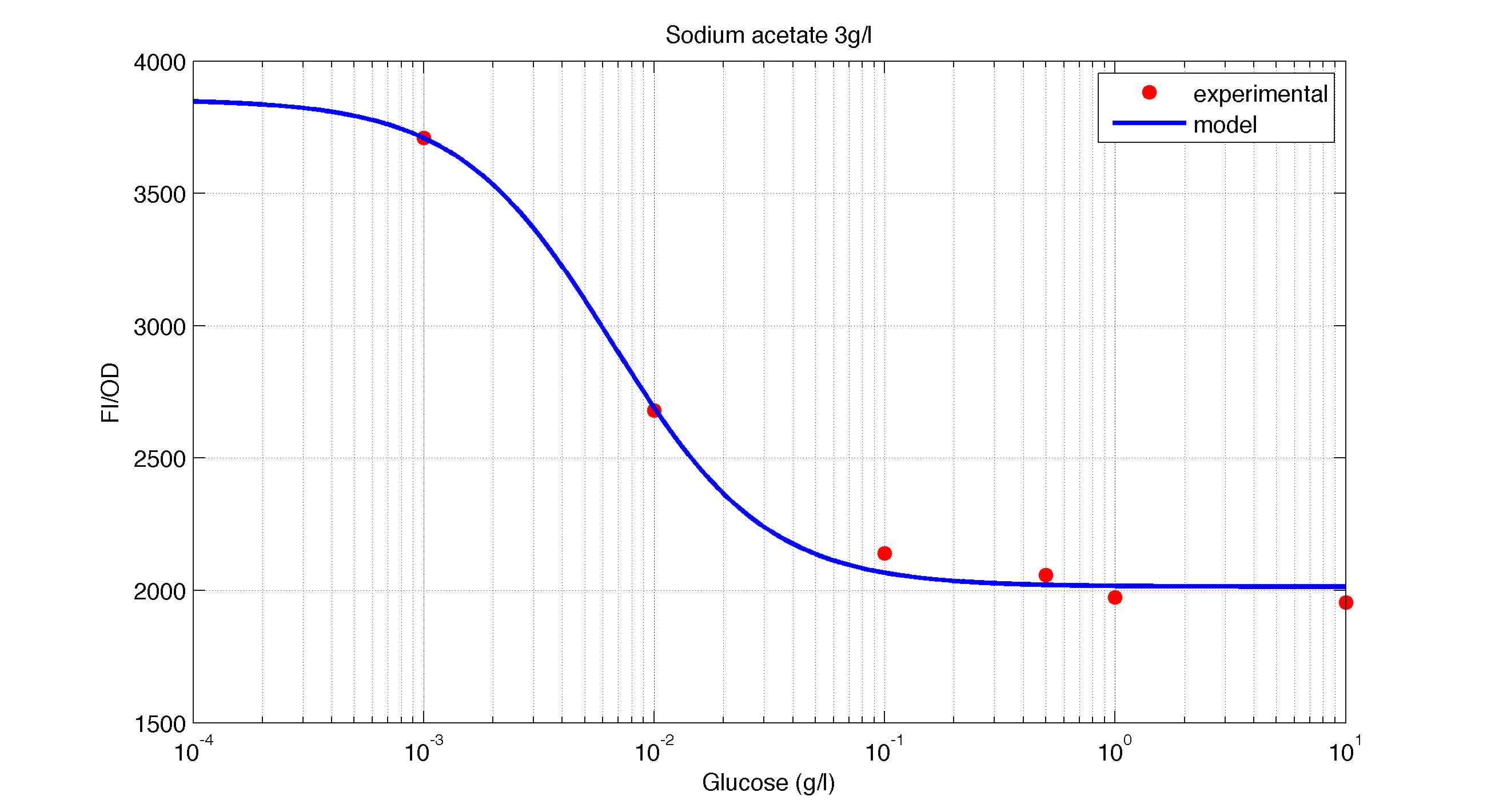

The first model we did addressed our glucose-sensitive construction. We carried out three different experiments changing the carbon source, to see its influence. First we used glucose (1) as the only carbon source. Then we added galactose (2) as an extra carbon source. Finally we put sodium acetate (3) as an extra carbon source instead of galactose. The use of alternatives to glucose is explained because in previous tests we observed that low concentrations of glucose compromised cell growth. With the experimental data we fitted the following repressible Hill-like function.

And we estimated the following parameters for the 3 different conditions.

In figures 1, 2 and 3 we plot the models and experimental data for the three experiments with glucose (1), added galactose (2) and added sodium acetate (3) respectively. IPTG was added to all the experiments to induce expression.

| Figure 1. Model and experimental data for different glucose concentrations. |

| Figure 2. Model and experimental data for different glucose concentrations with 3 g/l of Galactose added to the medium. |

| Figure 3. Model and experimental data for different glucose concentrations with 3 g/l of Sodium Acetatee added to the medium. |

It is interesting to notice how the Hill coefficient increases when adding Galatose and Acetate. From here we can hypothesize that having another source of carbon makes the promoter more sensitive to changes in the glucose concentration, as the slope of the Hill function gets larger. Also the constant K decreases, which tell us that less glucose is necessary to de-activate the promoter when there is another carbon source.

Compare this results with Are you hungry? results.

Are you hot?

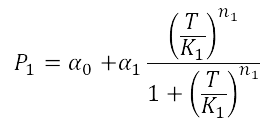

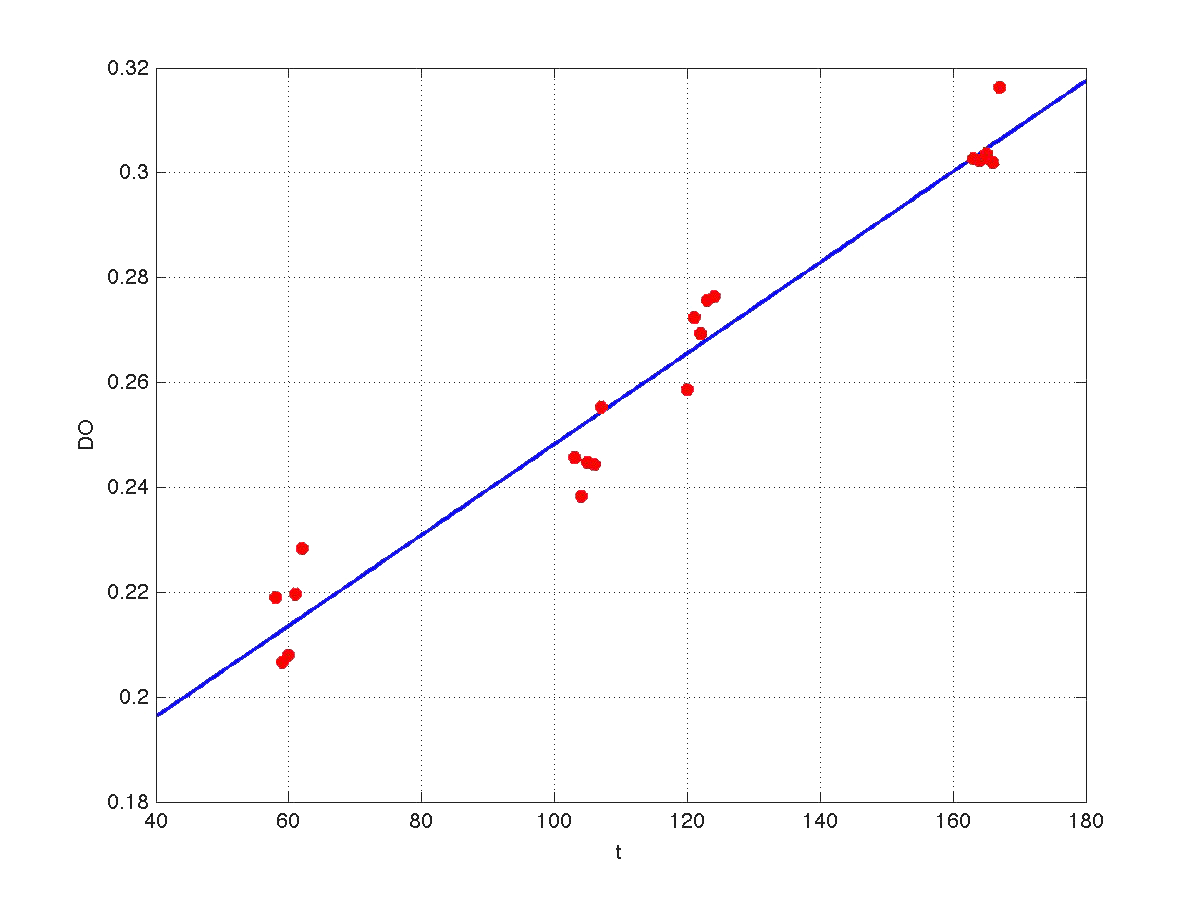

When analyzing the Heat Shock promoter, we decided to model the static transfer function of the Fluorescent Intensity as a result of the Temperature following the Hill-like equation:

In order to estimate the parameters of this model we performed a heat shock experiment.

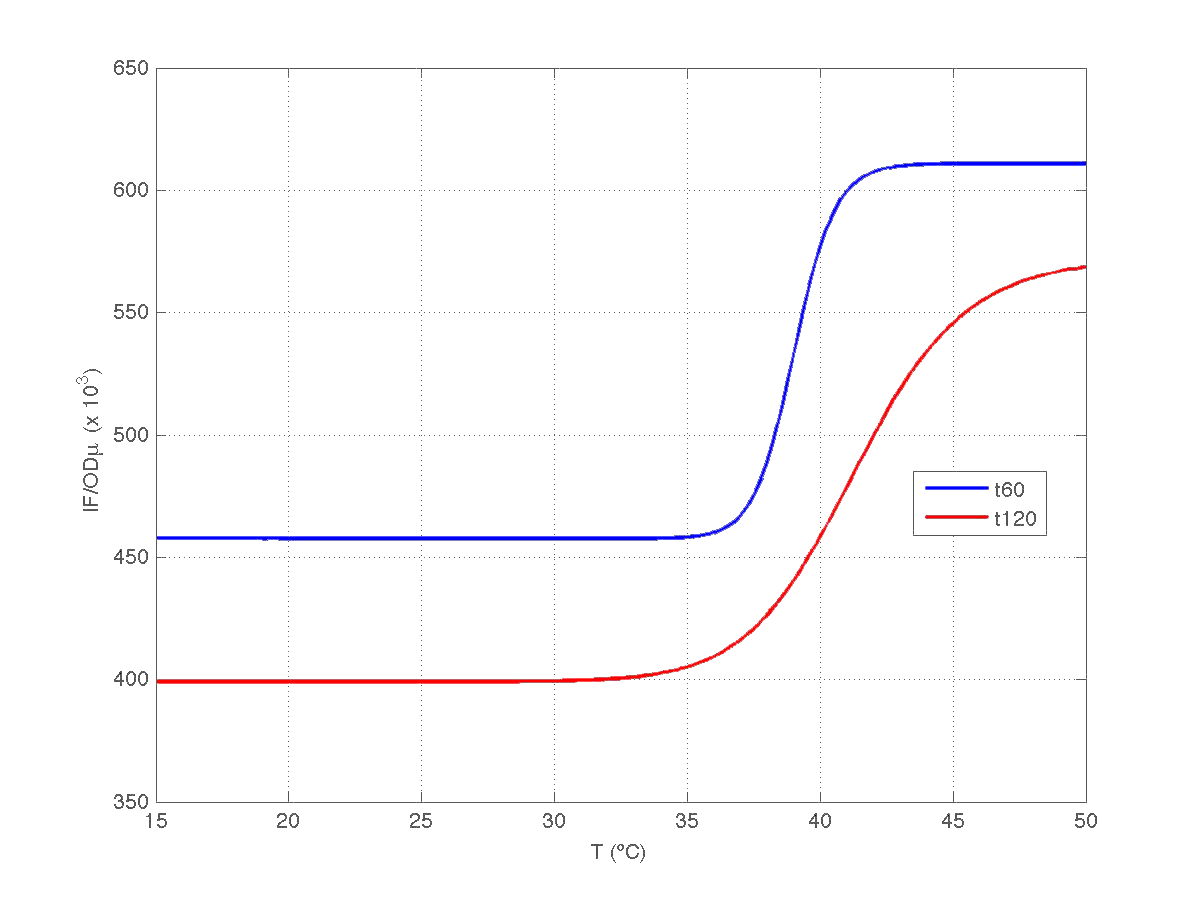

Our first analysis corresponds to a heat shock applied during 10 minutes at different temperatures, ranging from 20ºC to 51ºC. For each temperature three samples were tested. Fluorescence Intensity (FI) and optical density (OD) were measured at t1=60 min and t2=120 min after the application of the heat pulse had finished.

The first practical problem we encountered was the lack of enough heating coats. To try to solve it we took the culture and we split the experiments in two batches. FI and OD were measured at t1=60 min, and t2=120 min for batch number 1, while for batch number 2 the heat shock was delayed 40 min with respect to the first batch. Therefore, measurements for batch no.2 were taken at t1=100 min, and t2=160 min respectively.

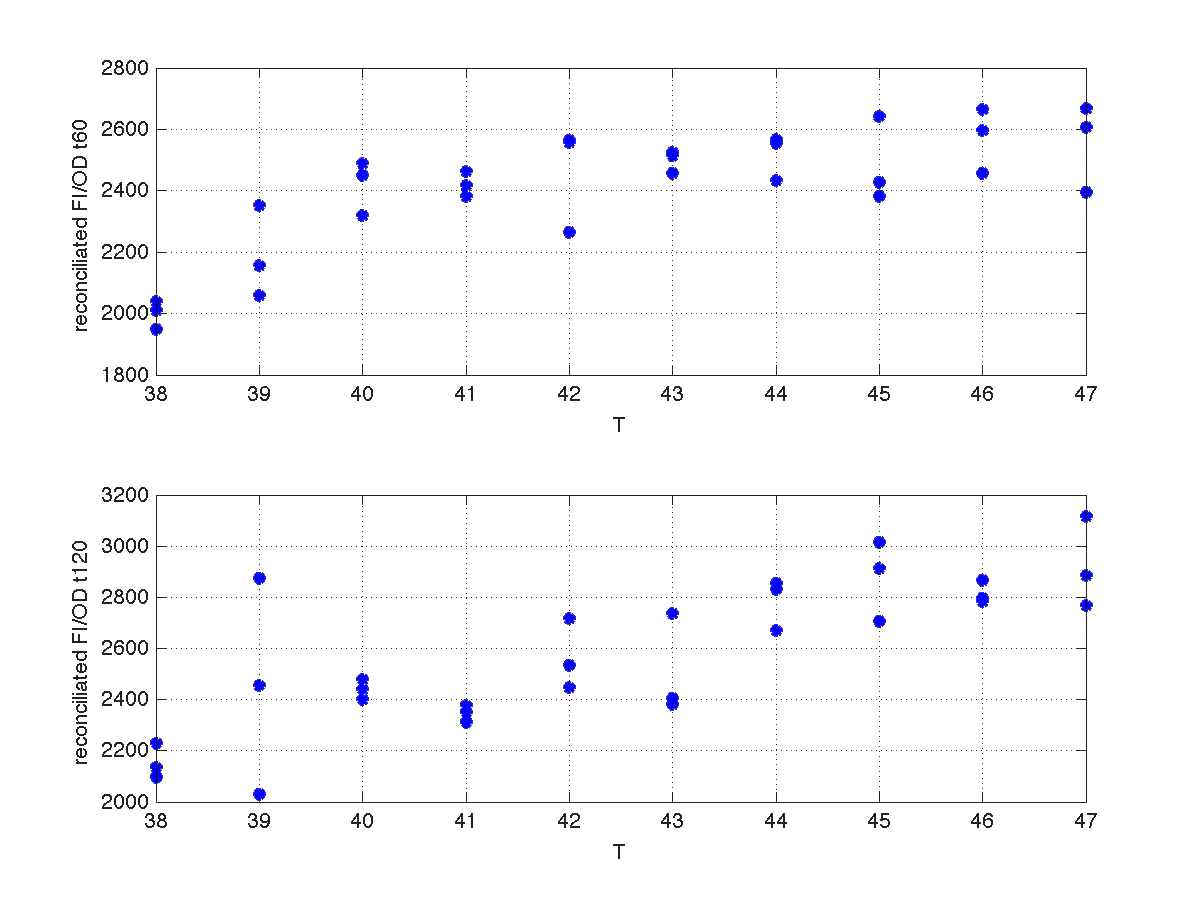

During the 40 min delay, the microorganism was growing. Therefore, the heat shock in batch no. 2 was applied to a larger population than in the case of batch no.1. Consequently, the measurements of FI and DO gave much higher values. This fact affects the ratio FI/DO, were the two batches can be clearly distinguished (see figure 4).

| Figure 4. Raw data from the heat shock experiment. |

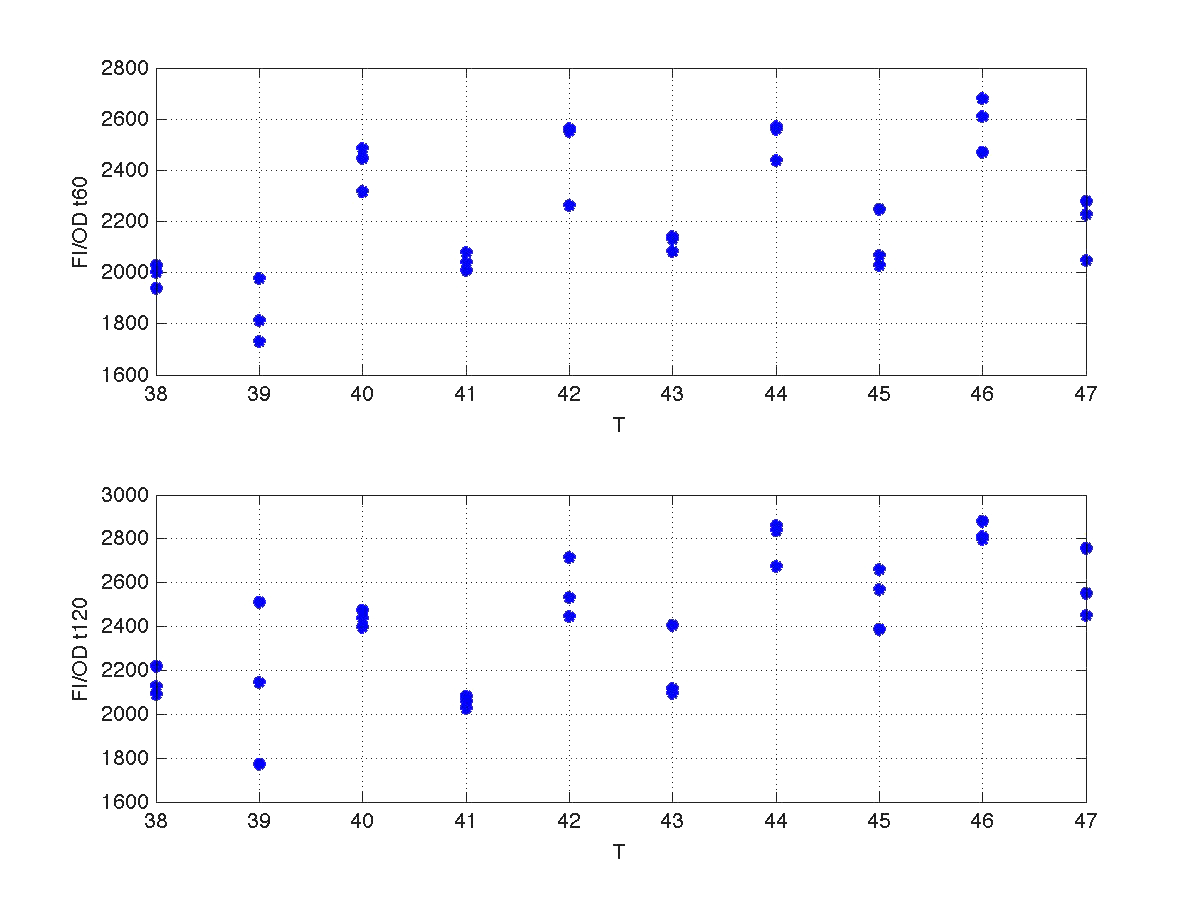

Our first modeling work was aimed to obtain data reconciliation. To this point, we assumed that, during this 40 min delay, the only thing that happened was that cells grew. Growth was approximately linear in the range analyzed, as seen in figure 1 (blue data). We fitted a simple model DO=p1+p2*t. The result can be seen in figure 5, were: p1 = 0.161573 p2 = 0.000866314 Therefore, the above ratio FI/DO can be compensated by multiplying data by the fractions (p1+p2*t100)/(p1+p2*t), and (p1+p2*t160)/(p1+p2*t). Actually, what we did was to compensate all measurements to the same time base. The reconciled results can be seen in figure 6.

| Figure 5. Model fitting for OD w.r.t. time. |

| Figure 6. Recoinciled data for t=60min and t=120min. |

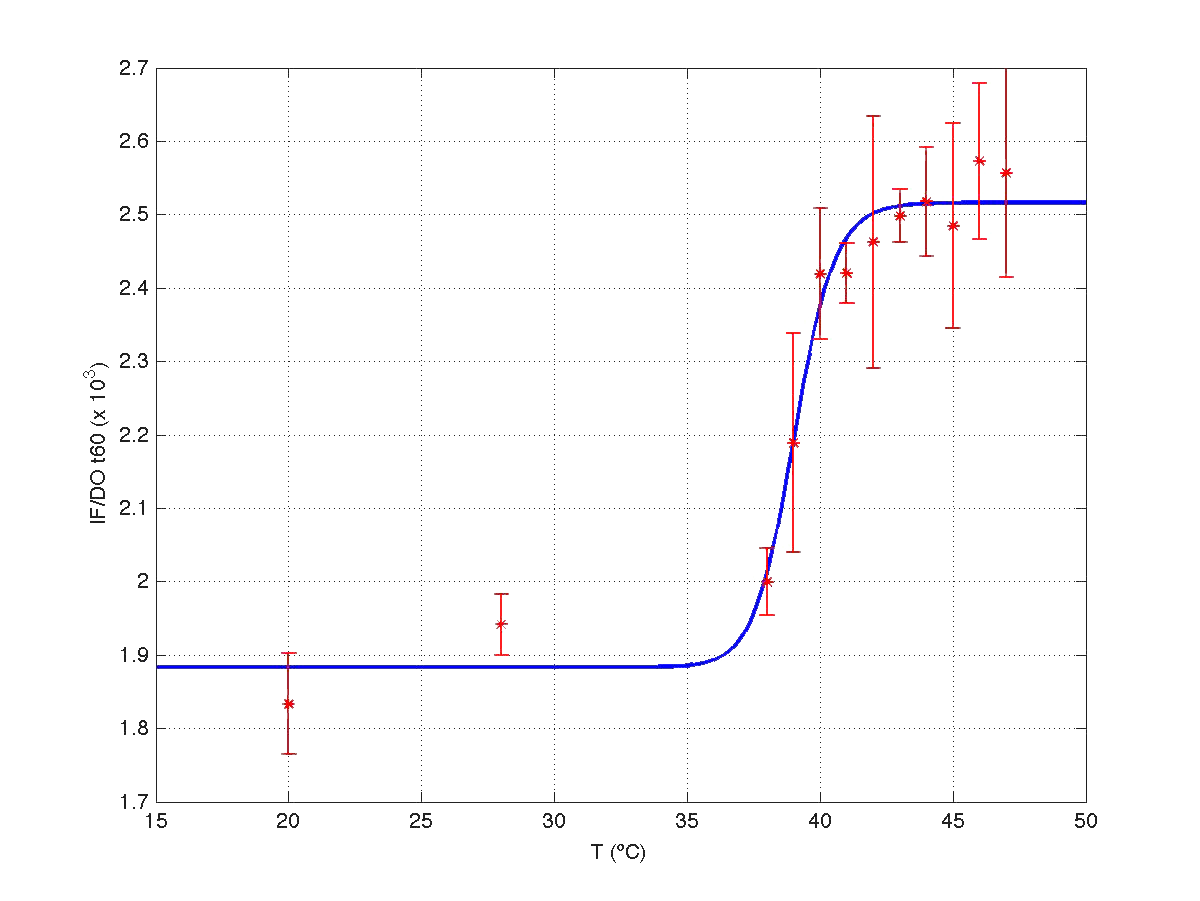

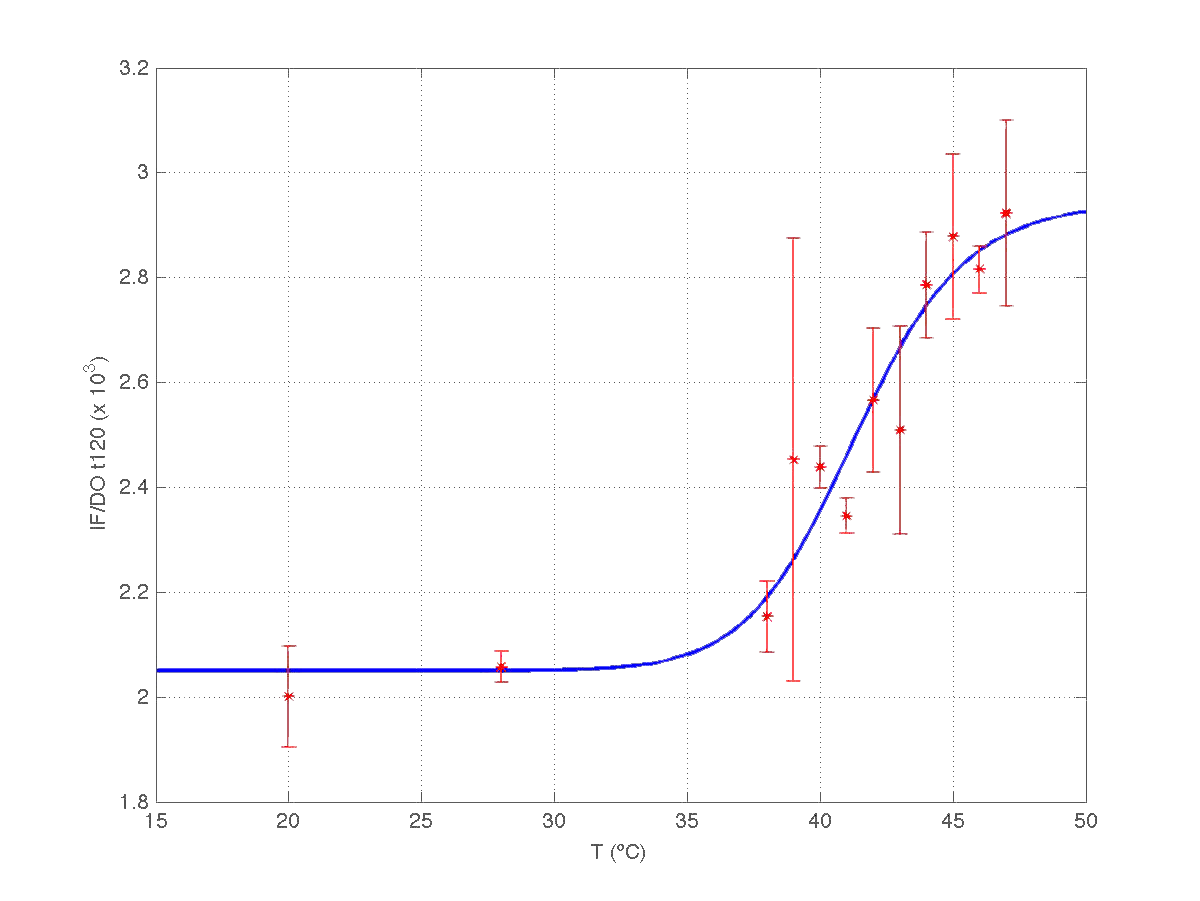

Once we had all data reconciled, we fitted them to a static model relating the ratio between fluorescence intensity (FI) and the culture optical density (OD) with the temperature applied during the heat shock.

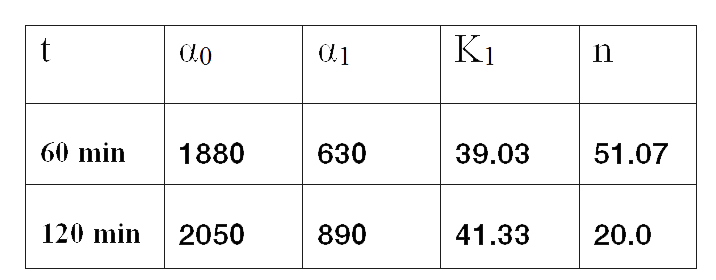

Since the model is nonlinear with respect to parameters K1 and n, we applied a global optimization algorithm based on stochastic search. Actually we applied it to fit the data at t=60 min, and t=120 min independently. The estimated parameters were:

The results can be seen in figures 7 (t60), and 8 (t120) respectively.

| Figure 7. Model and experimental data for t=60min. |

| Figure 8. Model and experimental data for t=120min. |

Compare this results with Are you hot? results.

One question of interest is whether the increment observed in the ratio IF/OD is caused by an incement of fluorescence during the time elapsed, or it is caused by a varying dilution effect due to a decrease in the specific groth rate during that period [1].

To answer this question notice that the absolute growth rate can be obtained from the regression model OD(t)= p1+p2*t obtained above. Notice t is expressed in minutes in our model. Indeed, the specific growth rate at time instant t can be roughly estimated as mu(t)= [dOD(t)/dt]/OD(t). This gives mu(t) = p2*60/(p1+p2*t) if mu(t) expressed in h^(-1).

Therefore, we took our models and weighted them by mu(t60) and mu(t120) respectively. The result can be seen in figure 6. Indeed, the increment observed in fluorescence from t=60 to t=120 minutes could have been caused by a dillution effect. Of course, the main point to keep is that the ratio IF/OD (or, alternatively IF/OD*mu(t)) increases with temperature. So...our construction works!

| Figure 9. Model IF/OD*mu(t) w.r.t. temperature for t=60min, and t=120min. |

[1] S. Klumpp, Z. Zhang, T. Hwa, Growth Rate-Dependent Global Effects on Gene Expression in Bacteria, Cell 139, 1366-1375, 2009

Modeling Yeast

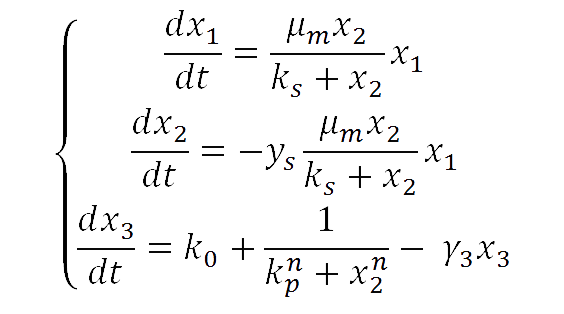

For our yeast construct: How long have you been fermenting? We propose a phenomenological model to explain the relationship between glucose concentration and fluorescent protein production. The following model was assumed:

where

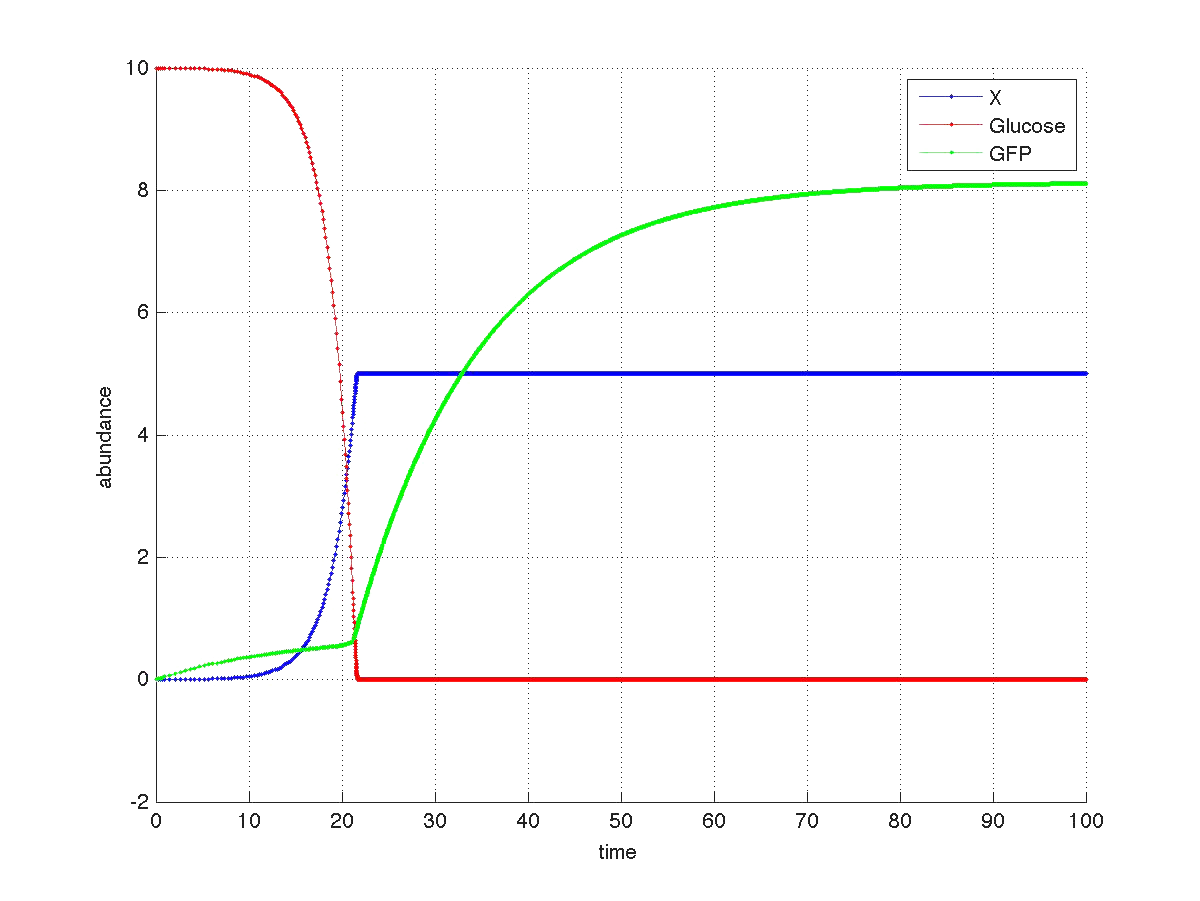

The graph below shows a simulated theoretical time evolution for the three variables.

As observed in the figure, once the glucose is depleted, the concentration of fluorescent protein increases from a basal value. Compare this results with Yeast fluorescence results

"

"