Team:Calgary/Project/FRED/Detecting

From 2012.igem.org

Hello! iGEM Calgary's wiki functions best with Javascript enabled, especially for mobile devices. We recommend that you enable Javascript on your device for the best wiki-viewing experience. Thanks!

A Transposon-Mediated Mutant Library for Toxin Detection

This year, our team wanted to identify a novel responsive element capable of detecting and quantifying different tailings ponds toxins (e.g. naphthenic acids, NAs) in solution. While numerous studies have begun to identify species of bacteria capable of surviving and sensing a variety of toxic compounds (e.g. NAs), the degradation pathways have not yet been fully characterized. Therefore, we needed to design and implement novel approaches to efficiently isolate the genetic elements that detect and potentially lead to the breakdown of these toxins.

Transposons: What, How, Why?

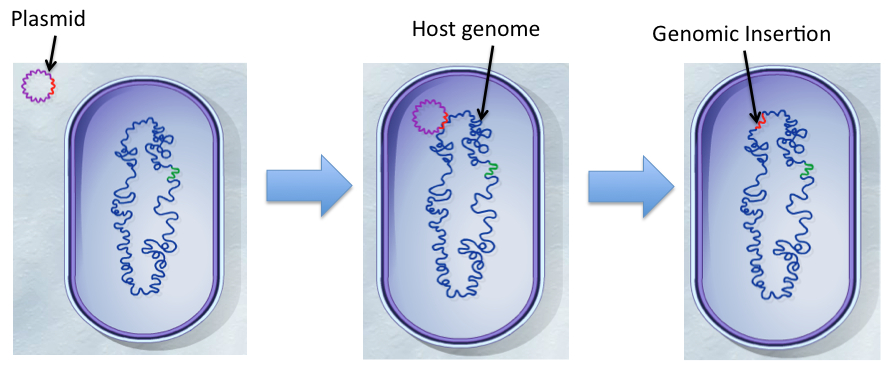

The transposable element (TE), Tn5, is a conservative transposon that can insert a segment of genes bordered by specific 19bp insertion sequences from one part of the genome (e.g. plasmid vector) randomly to another location like a chromosome (Reznikoff, 2008). The transposition event is catalyzed by a transposase enzyme encoded by tnp gene included in the TE. Using the appropriate selective pressure, the insertion can be maintained permanently in the genome.

By inserting a vector construct containing the TE with selectable markers (such as tetracyclin resistance and lacZ) into an organism with a desirable phenotype, we can find out what genetic elements (e.g. genes and promoters) are responsible for that particular function. This can happen via a random insertion of a TE containing a promoterless reporter gene downstream of promoter elements that creates a transcriptional fusion, providing activity in response to specific environmental stimuli. Using a bipartite-mating (conjugation) method to transfer the TE vector into the organism of choice is an efficient method for creating the massive number of mutants required.

Due to the complexity of biological systems, our team focused our efforts on utilizing a system for identification of promoter elements that respond specifically in the presence of environmental stimuli. Our hypothesis requires that the organisms we use respond specifically to particular toxins and result in upregulation of metabolic genes with little background effect in the cell. We recognize that any number of biological molecules may play a role in toxin sensing, such as enzymes, transcription factors, and even RNA elements (e.g. riboswitches). However, the identification of a promoter sequence takes us further in that we can better understand the degradation mechanism by elucidating the genes involved.

Toxin-Degrading Organism Used

Pseudomonas spp. have been isolated from oil sands tailings ponds and shown to biodegrade model and tailings-associated NAs and nitrogen- and sulfur-containing heterocyclic aromatic compounds (Ramos-Padrón et al. 2010; Herman et al., 1994; Del Rio et al., 2006; Gieg & Whitby, unpublished, 2012). This suggests that there exists systems that detect and up-regulate transcription specifically in response to these toxins.

We wanted to use a commercially available strain of Pseudomonas fluorescens characterized for a response to toxins found in tailings pond water (TPW). The P. fluorescens PF-5 strain (Paulsen et al., 2005) is reported to survive in and degrade a commercial mixture of naphthenic acids (Acros) (Gieg & Whitby unpublished, 2012). Moreover, the genome sequence is available for this strain with annotations (Pseudomonas Genome Database V2, http://pseudomonas.com/). This allows us to use sequencing data from the mutants and identify where in the genome the TE insertion occurred, and what genes (if present) are located downstream of it.

Method Design

Mutant Library Generation

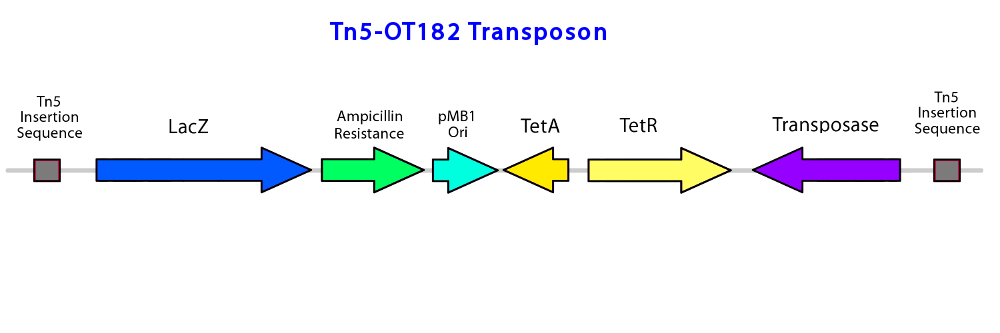

To construct the promoter library, a pOT182 vector construct (containing a IR-lacZ-Amp-pMB1ori-TetA-TetR-Tnp-IR transposable element) is introduced into commercially purchased E. coli SM10 donor strain.

The plasmid contains a RP4 mob conjugation region and a p15A origin of replication (ori), and is engineered to only replicate in E. coli. The TE construct is transferred from the E. coli donor strain to the recipient P. fluorescens PF-5 using bipartite mating via conjugation (enabled by the RP4 mob region). A random genomic library of transposon insertions is created in P. fluorescens, and selected by isolating the recipients that have a genomic TE insertion on Pseudomonas Isolation Agar/PIA with tetracycline. If a promoter element is fused upstream of the TE construct, then promoter activation will turn on the expression of lacZ, which can be detected by the degradation of a colorless compound, X-Gal, to an insoluble blue pigment product (an indoxyl compound) (Juers et al., 2012). If the fused promoter is activated in response to a stimulus, then the lacZ enzyme will be produced in response. Mutant strains sensitive to the particular toxic stimulus will appear as blue colonies on the selective plate.

Mutant Strain Characterization

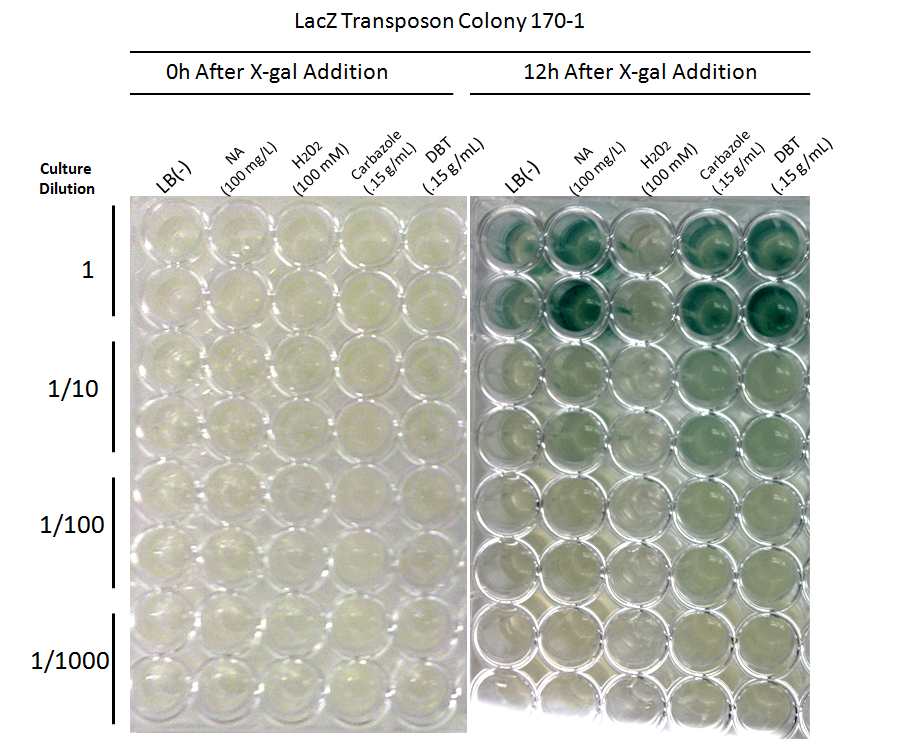

Mutants generated are characterized for their roles in the response to toxins with dose response experiments, and compared to general stress-inducing agents (e.g. H2O2) and compounds such as fatty acids to ensure the specificity of the response. These measurements help to determine thresholds of detection, robustness of the signal, and specificity of response. The dose response curves will also assess the usefulness of correlating the concentration of NA to the level of response, and the possibility of measuring NA concentrations in a sample, rather than simply by presence/absence.

Self-Cloning and Sequencing

Last, self-cloning techniques are used to identify the upstream and downstream sequences from the TE insertion (Merriman and Lamont, 1993). The TE used is a self-cloning construct because it contains all the elements required for plasmid replication (i.e. origin of replication) and selection (Tet resistance). Genomic DNA from a desirable mutant is isolated, and restriction digested with BglII (a restriction enzyme that does not cut within the TE but numerous times within the genome). The resulting fragments may contain the TE construct with flanking sequences. The genomic fragments are circularized by self-ligation and transformed into E. coli. Plasmids from the transformed cells contain the TE construct with the upstream and downstream flanking sequencing connected by the BglII restriction site. Sequencing primers designed against the 19 bp recognition sequence in the TE to sequence the isolated plasmids.

For a detailed protocol, please consult our methods section.

Results

Detection by Mutant Pseudomonas fluorescens PF-5

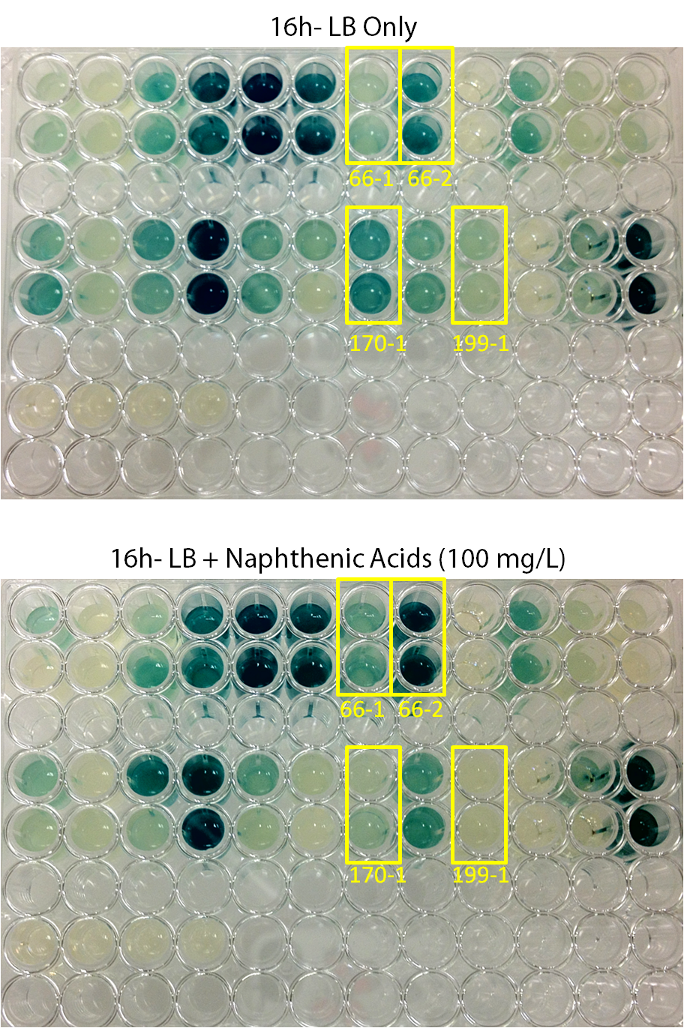

After mating experiments and plating on selective media (Pseudomonas isolation agar, with tetracycline and naphthenic acids), 24 responsive (blue) colonies were found. Screens were conducted on these blue colonies found on selective plates comparing a response in LB and LB with 100mg/L naphthenic acids (both with X-Gal). When results were observed it was found that 4 mutant strains are differentially regulated in response to naphthenic acids: 66-1, 66-2, 170-1, and 199-1. These colonies were further screened to test the specificity of their responses.

Screens involving the use of different toxins at environmentally relevant concentrations were performed to determine if the sensing response was specific to naphthenic acids, or if a sensory response to general toxins had been found. In addition, hydrogen peroxide was used as one testing condition to determine if the response is simply stress-induced.

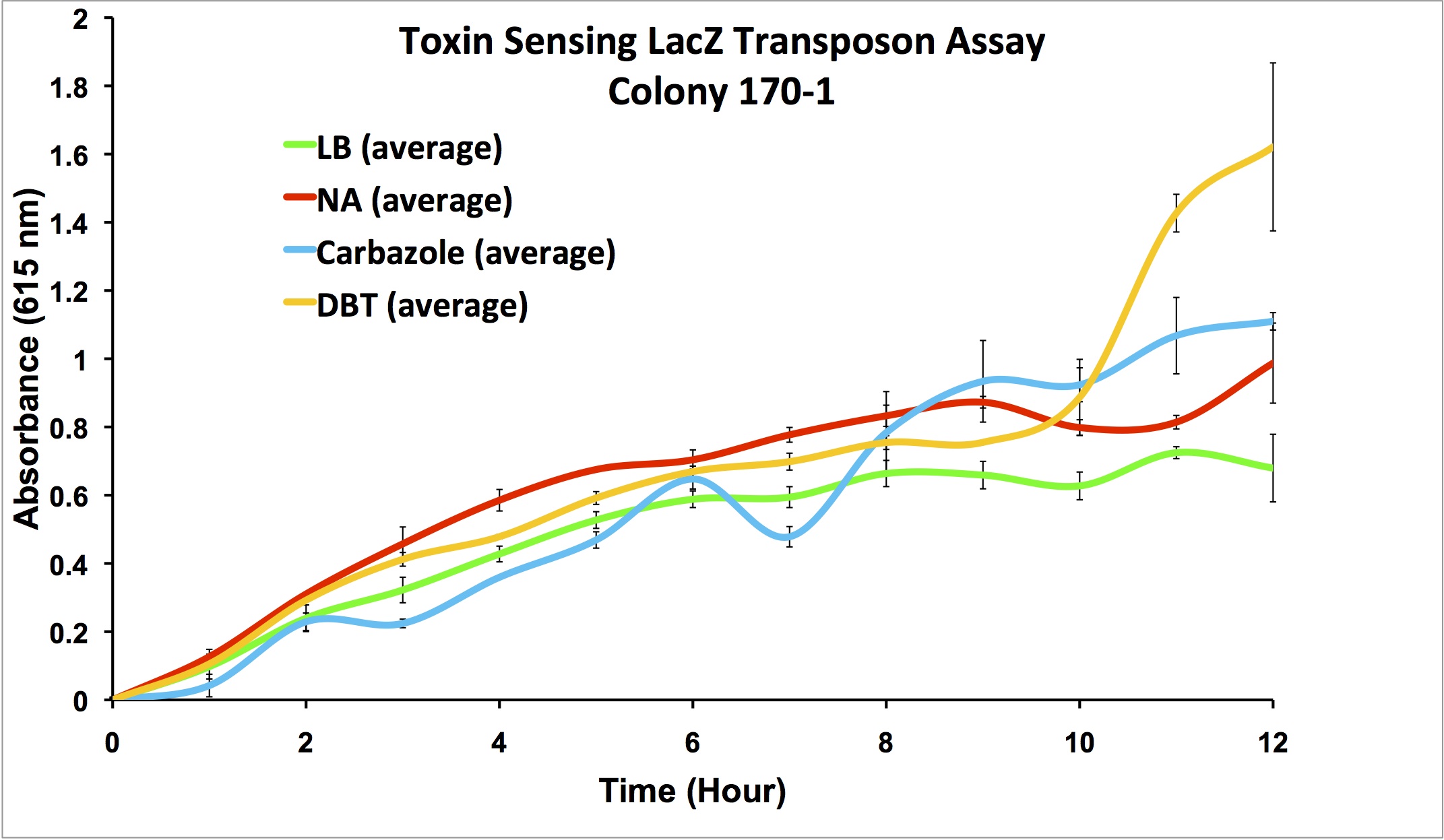

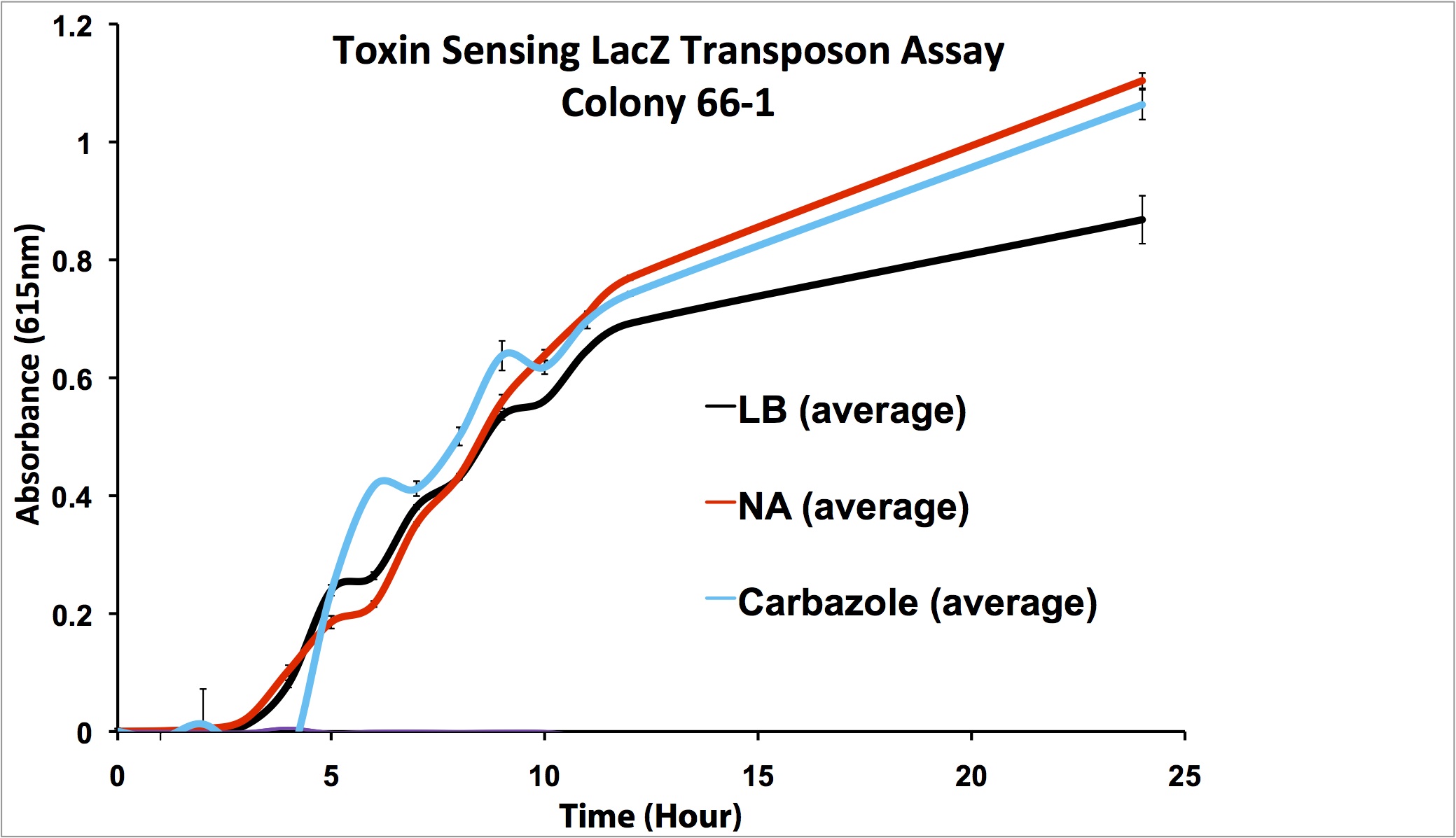

From these screens, it was seen that both colony 66-1 and colony 170-1 appear to respond to toxins when compared to a response in LB media. In order to test the specificity of this response, an additional screen was performed using varying concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (to rule out activation by a general stress response in the cell) in addition to decanoic acid at a comparable concentration to that of the naphthenic acids used (to rule out activation due to sensing fatty acid compounds). The results of this can be seen below.

These results show that colony 66-1 gives a response to naphthenic acids and other toxins that is not simply a response to fatty acids or a general stress response. Unfortunately, colony 170-1 does not show a useful reporter response.

Promoter Constructs Isolated

To determine the location of the transposon insertion, we utilized the self-cloning properties of the transposon. By digesting the genome, religating, and transforming the ligated genomic fragments into E. coli, plasmids containing the transposon and flanking gene sequences were isolated. These plasmids have been isolated and sent for sequencing. However, we are having difficulty with getting sequencing reactions to produce a read. The results so far are a promising step towards finding a sensory element for our reporter system that would allow for the detection of various toxins in tailings ponds. In tandem as we await sequencing results, our next steps will be to test these strains in conjunction with our electrochemical detector.

"

"