Team:Calgary/Notebook/Desulfurization

From 2012.igem.org

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

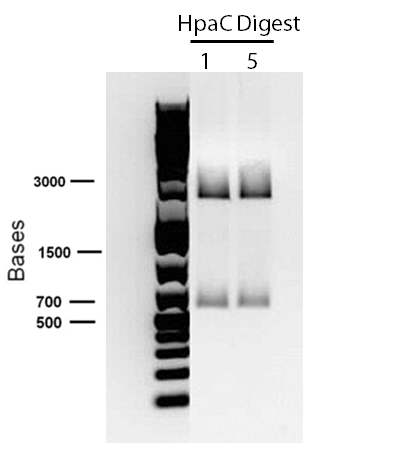

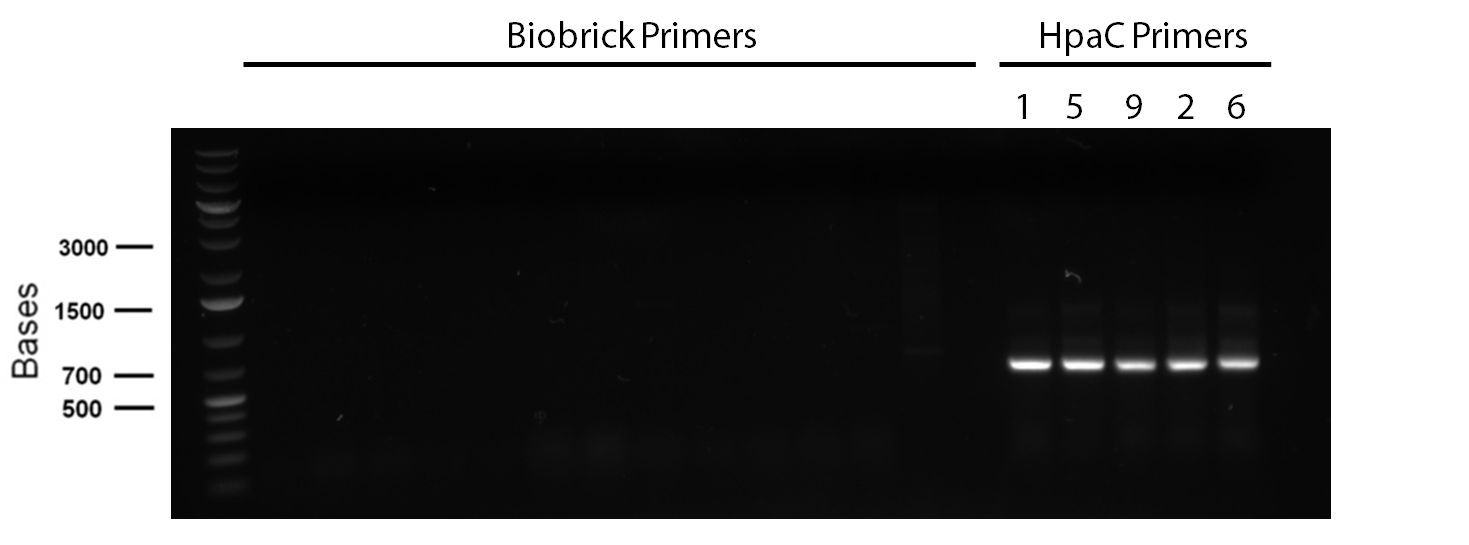

<p> In order to confirm the <i>hpaC</i> biobrick construction, two sets of colony PCR were performed, choosing white colonies from the 3 plates we grew last week (white colonies indicate a loss of the RFP generator in the pSB1C3 backbone, and therefore allow for weeding out of the colonies which are simply the original plasmid vector). These reactions were carried out both with <i>hpaC</i> primers and with standard biobrick primers designed against the plasmid backbone. After running them on the gel we saw equal bands for the PCR reactions performed using <i>hpaC</i> primers (However, a PCR using biobrick primers was performed later and the same results were obtained). Colonies 1(-) and 5(-) were used to make overnight cultures, which were then miniprepped the following day to obtain the plasmid DNA of the putative <i>hpaC</i> biobrick. Digestions were performed on the miniprep products using EcoRI and PstI to look for part size as further verification for the genes presence in the plasmid. The results were good and two bands were observed on each column (one for vector and the other for hpaC)). <i>hpaC</i> was sent in for sequencing. </p> | <p> In order to confirm the <i>hpaC</i> biobrick construction, two sets of colony PCR were performed, choosing white colonies from the 3 plates we grew last week (white colonies indicate a loss of the RFP generator in the pSB1C3 backbone, and therefore allow for weeding out of the colonies which are simply the original plasmid vector). These reactions were carried out both with <i>hpaC</i> primers and with standard biobrick primers designed against the plasmid backbone. After running them on the gel we saw equal bands for the PCR reactions performed using <i>hpaC</i> primers (However, a PCR using biobrick primers was performed later and the same results were obtained). Colonies 1(-) and 5(-) were used to make overnight cultures, which were then miniprepped the following day to obtain the plasmid DNA of the putative <i>hpaC</i> biobrick. Digestions were performed on the miniprep products using EcoRI and PstI to look for part size as further verification for the genes presence in the plasmid. The results were good and two bands were observed on each column (one for vector and the other for hpaC)). <i>hpaC</i> was sent in for sequencing. </p> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

| + | |||

</html>[[File:UCalgary2012_04.06.2012-desulfurisation_hpacverification.jpg|thumb|700px|center|Figure 2: HpaC verification cPCR. HpaC gene was inserted into the pSB1C33 vector and E. coli cells were transformed. In order to confirm that pSB1C3 contains the hpaC gene, two sets of colony PCR's were conducted. One with biobrick primers, and the other with hpaC primers. Bands indicate successful amplification at the approximate size of the hpaC gene (517 bp)]] | </html>[[File:UCalgary2012_04.06.2012-desulfurisation_hpacverification.jpg|thumb|700px|center|Figure 2: HpaC verification cPCR. HpaC gene was inserted into the pSB1C33 vector and E. coli cells were transformed. In order to confirm that pSB1C3 contains the hpaC gene, two sets of colony PCR's were conducted. One with biobrick primers, and the other with hpaC primers. Bands indicate successful amplification at the approximate size of the hpaC gene (517 bp)]] | ||

Revision as of 02:37, 2 October 2012

Hello! iGEM Calgary's wiki functions best with Javascript enabled, especially for mobile devices. We recommend that you enable Javascript on your device for the best wiki-viewing experience. Thanks!

Desulfurization Journal

Week 1 (May 1-4)

During this week, literature search was performed.

Week 2 (May 7-11)

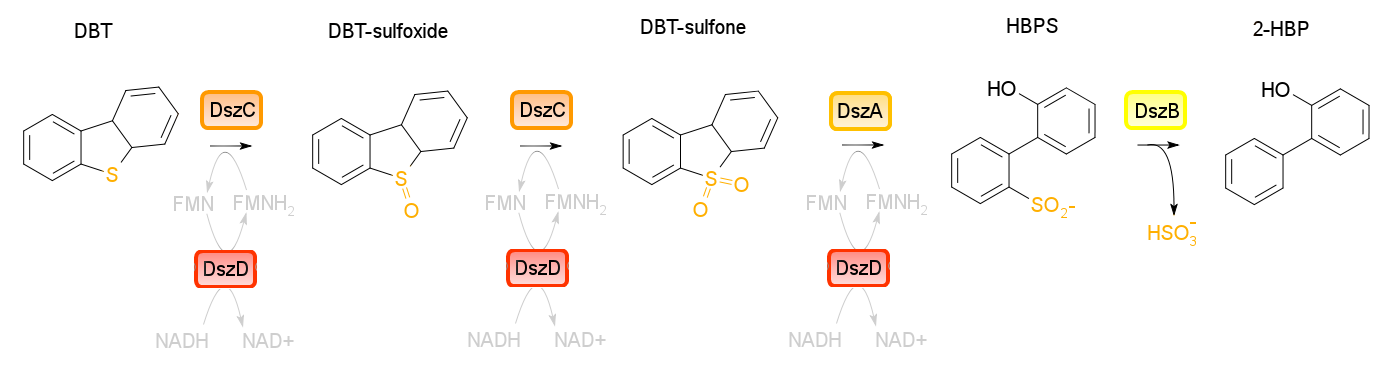

Along with the rest of the team, this week was dedicated to familiarizing ourselves on the protocols that will be utilized during this years project; specifically the polymerase chain reaction, gel verification, preparation of overnight cultures, as well as developing a procedural flowchart to transform competent cells with registry biobricks. With regards to our sub-group specific goals, we reviewed the current available literature around various industrial and laboratory approaches to desulfurization of organic groups, especially in the petroleum industry. This included a comparison of non-biological processes such as conventional hydrodesulfurization, which is currently employed in petroleum product refinery stages, and how a biological approach would supplement and perhaps even offer several advantages over these methods. Current limitations to biological desulfurization, however, include such factors as biocatalyst stability, enzyme specificity, desulfurization rate, and a need for a carbon source to regenerate co-factors. We also identified the enzyme desulfinase (DszB) as being one of the bottlenecks in the desulfurization 4S pathway. Overall, our goals moving forward involve determining the specific pathways involved in the desulfurization process as well as the reaction conditions we would want to employ, and identifying specific model compounds in addition to dibenzothiophene (DBT) that we could use to test the effectivity of our biosystem in order to determine its functionality in the conversion of naphthenic acids to economically valuable hydrocarbons.

Week 3 (May 14-18)

Building on the previous week's literature review, the 4S pathway was recognized as the preferred biological mechanism that we would explore in devising a desulfurization biosystem. Of specific interest is the dsz operon consisting of the genes for dszA, dszB, and dszC which selectively and non-destructively remove the sulfur from the hydrocarbon structure, and therefore preserves the carbon skeleton. In addition to these, another dsz gene exists. dszD, which codes for a FMN:NADH reductase, is an essential component of the pathway, but not part of the operon. Instead, it is encoded on the chromosome. The enzyme produced by this gene is required to regenerate the FMNH2 consumed by the reactions carried out by DszA and DszC. Rhodococcus erythropolis IGTS8 is the most studied model organism in investigations of the 4S pathway, and has been shown in many different research endeavors to be capable of converting DBT to 2-HBP.

An alternative to the DszD gene is HpaC, an oxidoreductase encoded in the E. coli W genome. This enzyme has been shown to increase the rate of desulfurization. Following this, other protocols added to our growing lab methods 'toolkit' were a restriction digest protocol, PCR purification, and finally, DNA construction digest. Aims moving forward include obtaining strains of the R. erythropolis , while also executing a timeline devised to biobrick, test, and incorporate the genes necessary in the above processes in a biobrick circuit.

Week 4 (May 22-25)

This week was kicked off with a project development meeting with Emily and David, and we devised a protocol for biobricking the hpaC gene. Additionally, methods to place the genes coding for the 4 enzymes, DszA,B,C and HpaC into a single construct were explored. Within the lab, the PCR performed on the resuspended pUC18-hpaC was not successful initially. Furthermore, we ordered the substrates/compounds that we intend to use for desulfurization tests. Once the substrates and the Rhodococcus strain arrive we are going to test how effectively the bacteria can desulfurize different sulphur-containing compounds that resemble naphthenic acids. Finally, we came across a paper where a team had developed an improved efficiency DszB through site-directed mutagenesis in 2007. This was through a point mutation to the gene, converting a tyrosine at position 63 to a phenylalanine residue. A member of this team was contacted to request the plasmid that contains the mutated gene. The conversion step carried out by DszB is the major bottleneck in the 4S pathway and if a strain or sample containing this mutation was obtained, it would significantly bolster our later testing efforts on DBT, as well as other compounds such as thiophane.

Week 5 (May 28 - June 1)

Since we wanted to make sure we would not run out of pUC18(plasmid containing the hpaC gene), we transformed some E.coli cells with it. We grew them on plates containing ampicillin (A), kanamycin (K), tetracycline (T) and chloramphenicol (C) antibiotics and they only grew on A. Therefore pUC18 has A resistance. We did a three sets of PCR with primers designed against hpaC, one using 1/10 dilution of pUC18, the other using 1/100 dilution of pUC18 and one with the colonies we had just obtained by transforming the E.coli cells. The PCR worked and we saw bands of the same size for all three sets of PCR. (Unfortunately, the picture we saved is not a good one since some of the bands faded away under UV due to prolonged exposure. Following this, PCR purification was performed to obtain the pure hpaC with biobrick prefix and suffix attatched to gene, which would allow us to insert the sequence into a biobrick standard backbone. 3 sets of digestion, ligation, and transformation (using pairs of X&P enzymes, E&S enzymes and E&P enzymes) were carried out in order to insert the hpaC gene into the pSB1C3 vector. All the sets grew successfully. Following the above successes with hpaC, the arrival of our Rhodococcus strain afforded us the opportunity to begin investigation of the Dsz operon using the primers current in our possession. This strain is an environmental isolate that has been shown to be an active desulfurizer. The gram-positive nature of the strain also dictated we explore various lysing strategies before the genes encoding the Dsz enzymes could be amplified for further purification and biobrick construction steps. PCR was carried out using dszA primers on three different treatments {microwave, lysate buffer, and a control} which yielded banding pattern around 1200 base pairs for the lysate treatment (2%SDS and 10% tritonX-100, plus heat for 5mins at 98C).

Week 6 (June 4 - June 8)

In order to confirm the hpaC biobrick construction, two sets of colony PCR were performed, choosing white colonies from the 3 plates we grew last week (white colonies indicate a loss of the RFP generator in the pSB1C3 backbone, and therefore allow for weeding out of the colonies which are simply the original plasmid vector). These reactions were carried out both with hpaC primers and with standard biobrick primers designed against the plasmid backbone. After running them on the gel we saw equal bands for the PCR reactions performed using hpaC primers (However, a PCR using biobrick primers was performed later and the same results were obtained). Colonies 1(-) and 5(-) were used to make overnight cultures, which were then miniprepped the following day to obtain the plasmid DNA of the putative hpaC biobrick. Digestions were performed on the miniprep products using EcoRI and PstI to look for part size as further verification for the genes presence in the plasmid. The results were good and two bands were observed on each column (one for vector and the other for hpaC)). hpaC was sent in for sequencing.

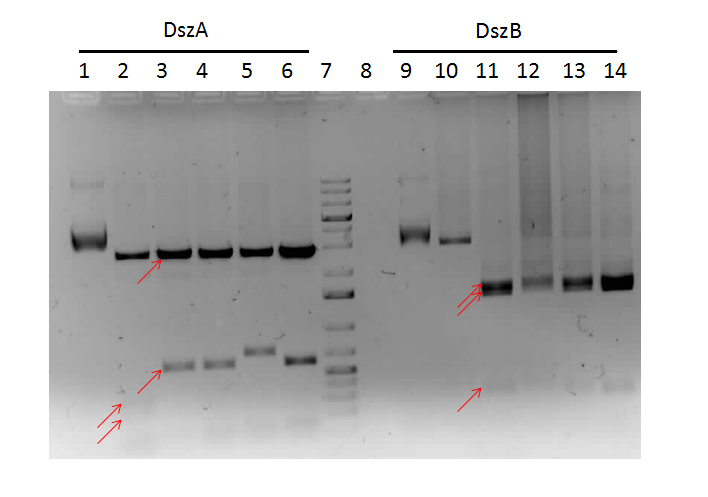

PCR reagents were prepared to re-test/confirm previous results of dszA amplification following two different lysing treatments (microwave + lysate buffer). This time, all three genes were amplified and gel verification showed clear banding patterns around 500bp range for all three genes for the microwave treatment. Remaining PCR products were run on a gel and extracted for further purification steps; however, presence of any genetic material were not confirmed through nanodropping which raised concerns about the composition of the purified products, the success of the initial amplification step, or perhaps even the lysis treatment. Further experimentation will have to be carried out to troubleshoot.

Week 7 (June 11 - June 15)

This week, we focused on amplifying dsz genes from our Rhodococcus strain for construction into biobricks. We also wanted to purify the PSB1C3-hpaC and pUC18-hpaC plasmids to replenish our current stocks. For the dsz aspect, we were able to successfully grow extra plates of Rhodococcus strain which was used to inoculate PCR tubes. The PCR did not go well, with significant streaking and false positives with similar banding pattern to previous gels run in the previous week. A final gel verification of a random sample of a tube of PCR products from dszA,B,C respectively and two negative control treatments involving master mix only and the lysed cells only illustrated the lack of discrepancy between the supposed successful amplification and the lysed cells (with lysate buffer) alone. Because of this we decided to take a different approach involving plasmid isolation carried out before PCR, rather than applying the PCR reagents directly to a lysed culture sample.

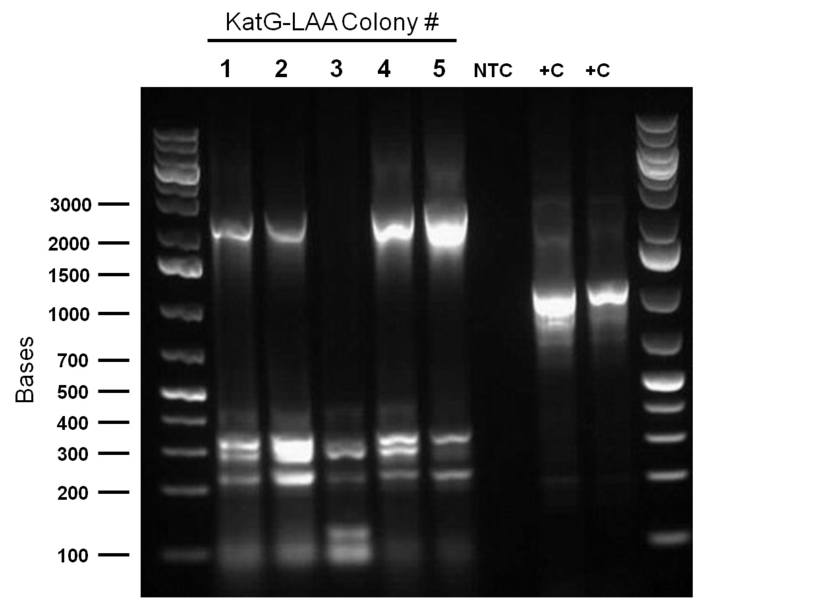

PSB1C3-hpaC verification through sequencing was successful, confirming the construction of our first biobrick. Subsequently, O/N cultures of the plasmid containing cultures were prepared and stored in glycerol at -80C. Furthermore, verification of catalase gene part (KatG-LAA, BBa_K137068), which was sent as a culture stab from the parts registry was initiated. Our newly identified biobricked-hpaC was used as a positive control, but the banding pattern was not very conclusive.

Week 8 (June 18 - June 22)

PCR was reattempted on Rhodoccocus that was lysed using two different dilutions of the lysate buffer, but the gel verification confirmed the previous failure in using this approach. An alternative that involved preparation of an overnight culture of the Rhodococcus cells followed by a plasmid purification was followed. The plasmid purification eventually yielded plasmid samples with concentrations of 98.6ng/uL to 182.7ng/uL (4 samples obtained overall). Additionally, the catalase biobrick was used to transform some stock competent cells, and samples of some colonies were subsequently PCR'ed. Although, the gel verification showed some potential contamination, and the required banding patterns at around 2200bp was not obtained.

Week 9 (June 25 - June 29)

PCR was attempted to amplify the genes of the dsz operon utilising an adapted PCR protocol with purified Taq polymerase that had been isolated from the host organism. Eventually, some banding pattern was obtained between 1200 and 1500 base pairs when a gradient thermocycler was used with melting temperatures ranging betweeen 55C to 65C. This was assumed to be indicative of successful amplification of dszB; however, further purification and gel verification results were inconclusive and no yield was obtained when placed tested using a nanodrop machine.

Week 10 (July 2-July 6)

Top 10 E.coli cells were transformed with BBa_R0011 (IPTG inducible promoter in psb1C3 backbone), and resulting colonies were tested using cPCR. Colony PCR was performed on cells containing the catalase biobrick. Catalase is 2217bp long but since biobrick primers add about 200bp, bands of 2400 bp were expected if the part was present in the biobrick. These bands were observed, indicating that the KatG-LAA gene was most likely present.

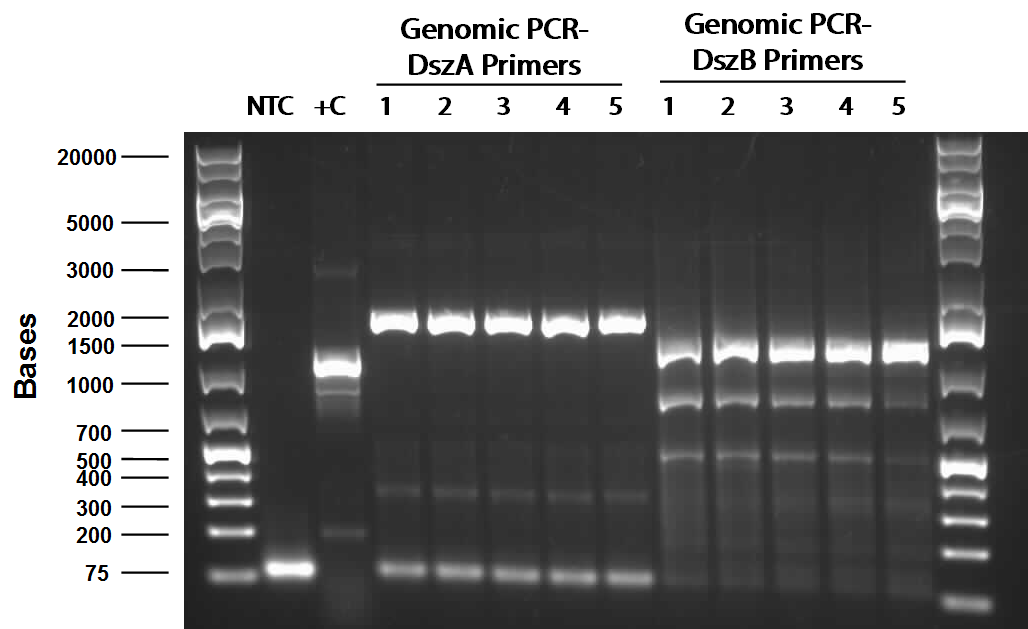

PCR using Phusion high fidelity polymerase was carried out on dszA, dszB, and dszC in a gradient thermocycler. Amplification of non-specific bands was present for dszA and dszB, however strong banding for the desired size of the gene was observed for both (around 1500 for dszA, 1100 for dszB

Examining the sequences of the dszABC genes led to the discovery that all 4 had multiple illegal enzyme cut-sites in them that we have to eliminate before biobrick composite part construction can occur. dszA has four PstI cut sites, dszB has a PstI and a NotI and dszC has a PstI cut site. The Stratagene QuickChange mutagenesis procedure is going to be used to eliminate illegal cut sites with the only alteration being that Kapa HiFi polymerase would be used during the process. Primers needed for the mutagenesis were designed based on the procedure mentioned above.

Week 11 (July 9-July 13)

Following successful amplification of the dsz operon genes in the previous week, the genes were constructed into the PSB1C3 vector. Colony PCR verifications were observed to be positive. Furthermore, the insertion of part J13002 (pTetR) in front of the previously biobricked hpaC was attempted. Overnight cultures were also prepared using two colonies each for J13002 and R0011 (an IPTG inducible promoter that we hope to build in front of B0034). These cultures were then miniprepped to yield the respective parts.

Additionally, katG-LAA was built into a PSB1C3 backbone. The construction and availability of all these parts will be critical in the construction of our overall circuit for biodesulfurization. Colonies which looked good on cPCR were used to prepare overnight cultures, and were miniprepped and sent in for sequencing verification the following day. On the side, M9 minimal media was also prepared to carry out growth experimentation and overall desulfurization capability of Rhodococcus when exposed to DBT. The various growth treatments were M9 Media and glucose only, M9+glucose+DBT, M9+glucose+MgSO4+/-DBT, M9+glucose+MgCl2+/-DBT. 0.008g of FeCl2.4H2O was also added to each of the tubes. Samples were then inoculated with colonies of the Rhodococcus.

Week 12 (July 16 -July 20)

This week, while awaiting sequencing verification results which were required before we could begin the construction process, the desulfurization team initially aided in some of the tasks related to the other hydrocarbon groups. The success of the construction of BBa_J13002 with hpaC was also explored by using forward and reverse primers of R0040 (the promoter component of the composite part J13002). However, the eventual gel verification was inconclusive and sequencing results finally indicated an unsuccessful ligation. Additionally, the minimal media M9 preparation had been contaminated in the previous effort so this process was repeated to create tubes of each of the growth condition treatments detailed previously, and two repeats, one with an extra filtration step and one without was used to prepare the cultures.

Week 13 (July 23 - July 27)

Mutagenic primers were redesigned after the initial ones were found to have premature stop codons. As part of the redesign process in constructing our overall gene circuits for desulfurization, a backbone switch of R0011 into a chloramphenicol (Chlor) resistant vector was necessary. The subsequent transformed products were plated on a Chlor plate and selected colonies were used to prepare O/N cultures, then minipreped before finally being digested with enzymes EcoRI and PstI. The resulting gel verification images were inconclusive as they did not show the required banding pattern around 50bp. Meanwhile, colony PCR was run on colonies transformed with katG-LAA constructed into a PSB1C3 backbone, as well as the hpaC+J13002 construct. katG was shown to have been successfully amplified, so overnight cultures were prepared and subsequently miniprepped. On the other hand, the construct was not successful so a third attempt was carried out. Colony PCR treatments that used either R0011 forward primers or B0034 primers were used and the overall constructs were made either on a chlor-resistant, or ampicillin-resistant vectors. Preliminary images of the gel verification appeared to have confirmed the construct, although sequencing verification will be the final indicator of overall success.

Week 14 (July 30 - August 3)

Sequencing results from the previous week's constructs were available confirming that we constructed KatGLAA in a chlor-resistant backbone. However, switching the plasmid backbone of R0011 to PSB1C3 was not successful. The construction of J13002+hpaC was finally sent in for sequencing. Site-directed mutagenesis of the dsz operon was also initiated: dszA has four PstI cut sites; dszB has a PstI and a NotI site; dszC has two PstI cut sites. Site directed mutagenesis was started this week to change a single base pair in these genes in a way that eliminates the cut site but preserves the amino acid codons, so as to not mutate the protein coding sequence. Ohshiro 2007 demonstrated that replacing the Tyr residue at position 63 of dszB gene with a Phe increases the activity of the enzyme. Therefore we want to introduce the same mutation into our dszB.

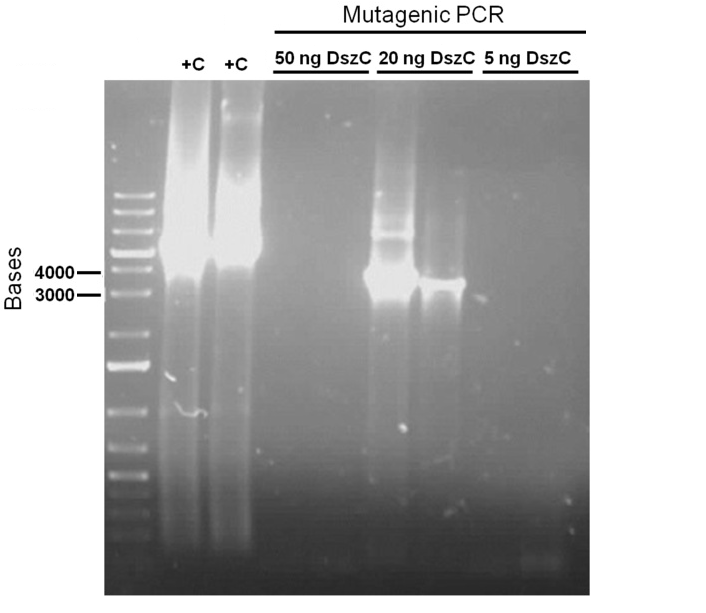

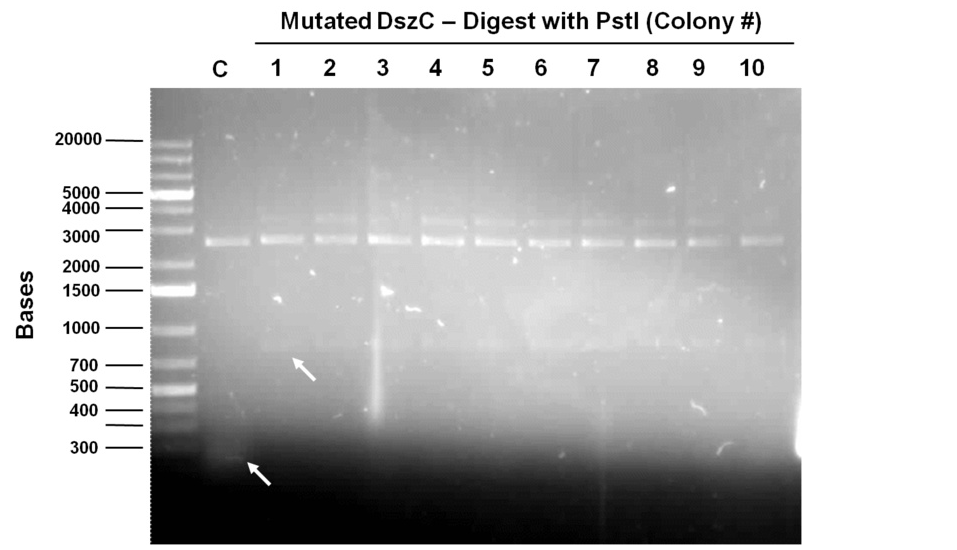

For the first attempt at mutagenesis we chose to mutate the second PstI site in dszC (PstI2). As a positive control for the procedure, we also performed the mutagenic PCR on a plasmid containing the β-galactosidase gene with a point mutation where the PCR would cause it to regain its function. For both mutagenesis protocols we used the Kappa Hifi kit. After confirming that the PCR worked by running some produce on a gel, the PCR products were DpnI digested, the purpose of which is to degrade the unmodified parental DNA (DpnI degrades methylated DNA only). Control PCR products were plated on an ampicillin plate containing IPTG and X-gal. The colonies that grew on the control plates were blue indicating that the mutagenesis had worked for the β-galactosidase gene. Minipreps of the O/N culture of dszC mutants were digested with PstI enzyme and the results indicated that the mutagenesis was successful.

Attempts to simultaneously perform all the mutations in dszC genes in one step using the Knight procedure failed (http://openwetware.org/wiki/Knight:Site-directed_mutagenesis/Multi_site). What enables simultaneous mutations is that Taq ligase closes the gaps in PCR products after each cycle. In the protocol it instructs to use Taq ligase buffer only for the PCR/ligation protocol. We suspected that the reason this procedure did not work might be that the Kappa polymerase is not functional in Taq ligase buffer. Therefore we did some experiments on the controls in Taq ligase kit and kappa polymerase kit to find out which buffer that Kappa polymerase and Taq ligase both work best in. The result was that both enzymes work best in a buffer made of half Taq ligase buffer and half Kappa polymerase buffer.

Week 15 (August 6 - August 11)

Sequencing results for J13002/hpaC returned negative, so a 3-part ligation method was used to retry this construction. The following parts were ligated with the restriction enzymes indicated in brackets after each: J13002(EcoRI/SpeI) + HpaC (XbaI/PstI) + PSB1K3 (EcoRI/PstI). Also, the more conventional construction (only 1 insert) of J13002(SpeI/PstI) + HpaC(XbaI/PstI) was reattempted. Furthermore, 3-way ligations were also attempted for B0034+KatGLAA+PSB1K3, and R0011+B0034+PSB1C3, as well as the two-way contruction of just KatGLAA after the B0034. After plating these transformations, colony PCRs were carried out and samples that gave an indication of being successful on the gels were used to prepare O/N cultures followed by miniprep. With regards to the site-directed mutagenesis side of the experimentation, dszA-PstI1 (the first PstI cut site in dszA) , dszB-PstI and dszC(PstI2 mutated)-PstI1 mutagenesis were performed following the procedure explained in the previous week. The gel below shows the successful result of digest confirmation (Fig. 8). Multisite mutagenesis (Knight method) was repeated using the modified buffer (half Taq ligase buffer and half Kappa buffer). However it was not successful again. We also tried doing multisite mutagenesis using Pfu Turbo polymerase and following the Knight procedure without any buffer modifications. No successful results were observed.

Week 16 (August 12 - August 18)

The progress in mutagenesis of dsz genes was continued from the previous week: dszB(PstI mutated)-Y63F and dszA(PstI1 mutated)-PstI3 mutagenesis. The gel below shows the digest confirmation.

We attempted a different approach to speed up the turnover time of the mutagenesis PCR. Briefly, after the PCR mutagenesis the PCR products were purified and then incubated with T4 polynucleotide kinase (PNK) and ligase. After heat inactivating the ligase and T4 PNK, the products were DpnI digested. Subsequently another round of DNA purification was performed. However, the results were unsatisfactory after the digest confirmation.

Sequencing results came back. dszA (PstI1 and PstI3 mutated) and dszB(PstI and Y63F mutated) were good. However dszC (PstI1 and PstI2 mutated) had an insertion next to the PstI1 cut site. Mutagenesis was repeated on the dszC(PstI2 mutated). dszB(PstI and Y63F mutated)-NotI and dszA(PstI1 and PstI3 mutated)-PstI4 mutagenesis were also performed.

To investigate the desulfurisation capability of the Rhodococcus sp. from which we cloned the dsz operon, a desulfurization assay was prepared by inoculating different treatments of M9 media. We also prepared some solutions that will be needed for analysis in the following week: a conditioning agent composed of 100ml of 95% ethanol, 50ml glycerol, 30ml of 12M HCl (aq) and 70g of NaCl(s) was prepared. The assay relies on the turbidity of a sample containing sulphate ions which are precipitated (hence the turbidometric nature of the assay) upon adding BaCl2(s), therefore if the dsz pathway is active, we expect a more turbid solution to form than in control samples.

Elsewhere, B0034 was constructed with dszC and of the colonies that grew on the plate of the transformed products, colony PCRs were performed. The gel image gave an indication of a successful construct, however, further analysis through sequencing showed that the constructions were not successful, and so the constructions were restarted.

Week 17 (August 19 - August 25)

This week, progress was made in determining the desulfurization activity of our Rhodococcus strain as measured by the sulfate release using a turbidometric assay. We encountered several challenges in our prescribed protocol as the concentrations that we used to prepare the standard curve may have been too dilute, or the composition of out conditioning agent may have been flawed. Additionally, steps were taken to determine the decomposition of DBT to 2-HBP through Gas Chromatograph-Mass Spectroscopy (GC-MS) analysis, but due to a preparation error, the DBT was added to a growth solution of M9 media prematurely and the autoclaving process decomposed the DBT releasing a yellow colouration into the solution. These two approaches in determining the desulfurization capability of the dsz operon will be further investigated.

Since the dszC second mutagenesis had proven to be unsuccessful last week, the dszC(PstI2 mutated)PstI1 mutagenesis was repeated. Also dszA(PstI1,3,4 mutated) PstI2 mutagenesis was performed. dszA and dszC were sent for sequencing on Wednesday. dszB was sent for sequencing on Friday. Sequencing results of dszA and dszC were back by Friday. dszC was successful. However, dszA contained an insertion next to the binding site of PstI4 cut sit, so the last two mutations must be redone. dszB(PstI and Y63F mutated)-NotI-mutagenesis was also repeated in case the result of the sequencing was not successful. These constructions were repeated. J13002-dszB and B0034-dszC constructions were attempted, however they were not successful as indicated by colony PCR. Constructions of J13002/hpaC were carried out and also came back negative in sequencing, however B0034/katG-LAA was sequence confirmed.

Week 18 (August 26 - September 1)

dszB sequencing results came back as successful. dszA(PstI1,3 mutated)-PstI2-mutagenesis was performed and sent for sequencing. Also dszA(PstI1,2,3 mutated)-PstI4-mutagenesis was performed, and this was also sent for sequencing.

Constructions of J13002/dszB and B0034/dszC were attempted, verification digested, and sent for sequencing. Sequencing results for these constructs came back as positive, along with successful mutagenesis of dszA

At this point, all of the dsz genes have been successfully made biobrick compatible, and hpaC has been biobricked. We have also successfully constructed B0034 with katG-LAA to be used in the optimization circuit, as well as J13002/dszB and B0034/dszC.

Constructions of J04500 with hpaC, dszB, and katG-LAA were performed. As well, attempts to construct J13002/dszB/B0034/dszC as well as J13002/hpaC, B0034/dszA, and J13002/katG-LAA were also carried out. These parts are intended as construction intermediates towards building the final systems, as well as providing a way of testing the genes functionality (namely, to test HpaC for oxidoreductase activity and to test if over-expression of KatG in the cell will increase its ability to survive H2O2 stress). Transformations of all these constructions were carried out at the end of the week.

Week 19 (September 2- September 8)

Confirmation digests on colonies of the previous constructions that gave bands of the expected size with cPCR were performed. Positive results were found for colonies of J04500/hpaC, J04500/dszB, and B0034/dszA. Sequencing was sent, and results indicated that the constructions of J04500/hpaC were successful, meaning that after many months of trying we FINALLY have a promoter in front of the hpaC gene and can proceed to test the parts functionality. Attempts to construct hpaC with the evil TetR promotor (J13002) were abandoned, as it was believed that this construction was failing due to toxicity of over-expressing the protein, and it was determined that this part was not necessary after all. J04500/dszB also worked, though this was less exciting. B0034/dszA came back as a bad read despite looking very good on the confirmation digest gel, so this part will be resent for sequencing. Constructions of J04500/katG-LAA were reattempted, and confirmation digests for this part looked good, and so samples were sent for sequencing.

Week 20 (September 9- September 15)

Construction attempts on J13002/dszB/B0034/dszC, J04500/dszB/B0034/dszC, and J04500/hpaC/B0034/katG-LAA were performed. Colonies grew for the constructions, however further confirmation results were dissapointing (only 2 clones of J13002/dszB/B0034/dszC appeared to have been successful). These clones were sent for sequencing, and constructions were reattempted.

However, when sequencing came back, somehow reads indicated that these clones were in fact a gene from the Denitrogenation project (which is 990bp and a completely different band then what we saw on the gel). We believe, somewhere, something has gone very wrong- further investigation into this will be carried out. In the meantime, the above constructions were reattempted., and B0034/dszA was re-prepped in case a contaminant in the plasmid stock was to blame for the bad reads found in this batch of sequencing as well as the last. In addition, plasmid switches of multiple sequence confirmed parts into a pSB1C3 backbone were carried out.

Week 21 (September 16- September 22)

Colonies for the transforms of J13002/dszB/B0034/dszC, J04500/dszB/B0034/dszC, and J04500/hpaC/B0034/katG-LAA have been few and far between, and cPCR results are always discouraging. Sequencing results for other sections of the project have once again come back very confusing, and further research continues into the source of this madness.

Week 22 (September 23- September 29)

Attempts to construct J13002/dszB/B0034/dszC, J04500/dszB/B0034/dszC, and J04500/hpaC/B0034/katG-LAA continue. In the meantime, J04500-KatG was tested for functionality. In order to do this, cultures of J04500-KatG were grown up overnight in LB media. A strain carrying J04500 only was used as a negative control. The following morning, 20 µL of each culture was inoculated into 3 mL of LB with various concentrations of hydrogen peroxide; 0 mM, 1 mM, 5 mM, and 10 mM. These cultures were then allowed to grow overnight, and culture turbidity was observed. It was found that the negative control exhibited no growth after 12h at 1 mM peroxide, however cultures with induced expression of catalase were turbid after 12 h of growth at this concentration (Fig. 10). This demonstrated the ability of the catalase to protect the cells from excessive peroxide concentrations.

"

"