Team:Calgary/Project/OSCAR/Desulfurization

From 2012.igem.org

m |

|||

| (104 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

CONTENT=<html> | CONTENT=<html> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2012/5/5e/UCalgary2012_OSCAR_Desulfurization_Low-Res.png" style="float: right; padding: 10px;"></img> | ||

<h2>Why Remove Sulfur?</h2> | <h2>Why Remove Sulfur?</h2> | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | + | <p align="justify"> | |

| - | + | Sulfur is the third most abundant element in crude oil (Ma, 2010), and when sulfur containing hydrocarbons are burned they release S0<sub>2</sub> and S0<sub>3</sub> gasses into the atmosphere. Not only does this reduce the efficiency and value of our product, but it also contributes to global warming, acid rain, and various health issues due to the pollution (Reichmuth <i>et al</i>., 2000). Strict regulation on sulfur in fuels are now in place and low-sulfur gasoline is mandated across all of Canada (Source: Environment Canada). To upgrade the quality of our fuel we need to remove the sulfur but keep the hydrocarbon backbone.</p> | |

| - | + | ||

| + | <h2>Our Vision</h2><p align="justify"> | ||

| + | Though a few pathways for biodesulfurization exist in the microbial world, most involve the destruction of part of the carbon skeleton (an example would be the Kodama pathway)(Soleimani <i>et al</i>., 2007). This would effectively reduce the quality of our product. With this in mind the pathway we have chosen is the 4S pathway found in <i>Rhodococcus spp</i>. It has been characterized and shown to remove sulfur from the model substrate dibenzothiophene (DBT) and convert it to 2-hydroxybiphenyl (2-HBP) in a non-destructive manner. DBT and its derivatives make up 70% of the organic sulfur compounds found in crude oil (Ma 2010), and are also some of the most difficult to remove through chemical means. By using the 4S pathway we will be able to upgrade our fuel and remove recalcitrant compounds at the same time. | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

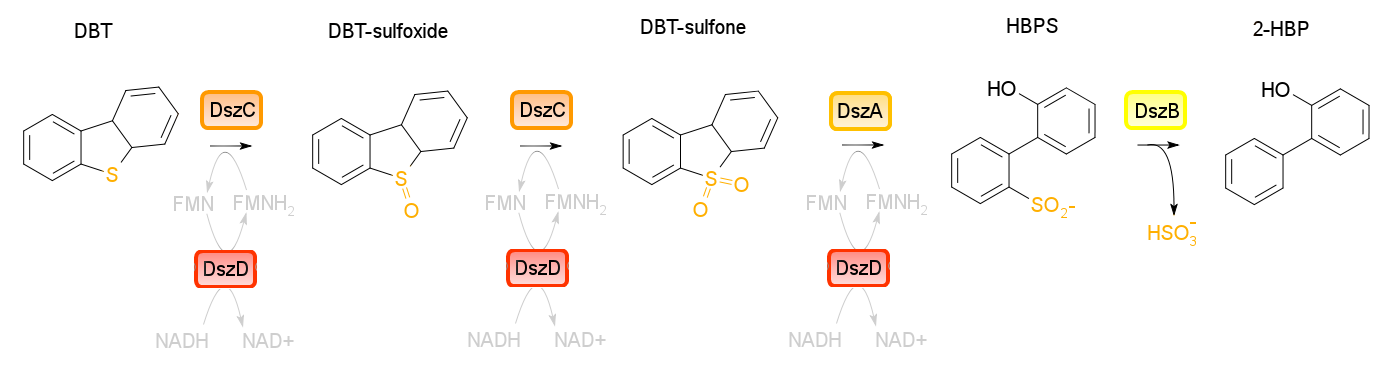

| - | </html>[[File:Ucalgary_team_sulfur_4s_enzyme_pathway_diagram.png|center| | + | </html>[[File:Ucalgary_team_sulfur_4s_enzyme_pathway_diagram.png|center|750px|thumb|Figure 1: The 4S Desulfurization Pathway, showing the desulfurization of the model compound DBT by DszA, DszB, DszC, and DszD.]]<html></p> |

<h2>4S pathway</h2> | <h2>4S pathway</h2> | ||

| - | <p> | + | <p align="justify"> |

| - | Four enzymes are involved in the 4S pathway, 3 of which are directly involved in the conversion of DBT to 2-HBP. Dibenzothiophene monooxygenase (DszC) is responsible for the first two steps of the pathway, converting DBT to DBT-sulfoxide and finally to DBT-sulfone (DBTO<sub>2</sub>) through the addition of oxygen to the sulfur atom. DBT-sulfone monooxygenase (DszA) then carries out the next step in the pathway, producing 2-hydroxybiphenyl-2-sulfinic acid (HBPS) through addition of a final oxygen to the heteroatom. This causes cleavage of the chemical bonds at the | + | Four enzymes are involved in the 4S pathway, 3 of which are directly involved in the conversion of DBT to 2-HBP. Dibenzothiophene monooxygenase (DszC) is responsible for the first two steps of the pathway, converting DBT to DBT-sulfoxide and finally to DBT-sulfone (DBTO<sub>2</sub>) through the addition of 2 oxygen atoms to the sulfur atom. DBT-sulfone monooxygenase (DszA) then carries out the next step in the pathway, producing 2-hydroxybiphenyl-2-sulfinic acid (HBPS) through addition of a final oxygen to the heteroatom. This causes cleavage of the chemical bonds at the sulfur, breaking the ring and converting the compound from a 3-ring structure to a 2-ring structure. HBPS is then converted to the final product of the 4S pathway by HBPS desulfinase (DszB), producing 2-HBP. At this point, the sulfur has been released from the hydrocarbon in the form of sulfite.</p><p align="justify"> |

| - | The first three steps of the 4S pathway | + | The first three steps of the 4S pathway require FMNH<sub>2</sub> and subsequently reduces the reductive power of the cell. WIn order to regain this power an oxidoreductase (DszD) uses NADH to recycle the FMNH<sub>2</sub>, allowing the reaction to proceed. Without DszD the desulfurization pathway would grind to a halt.</p><p align="justify"> |

| - | + | The <i>dszA</i>,<i>B</i>, and <i>C</i> genes form an operon on the pSOX plasmid of <i>R. erythropolis</i>, while <i>dszD</i> is found in the chromosome. Naturally this pathway is slow, however using synthetic biology approaches this process can be optimized.</p> | |

<h2>Our Approach</h2> | <h2>Our Approach</h2> | ||

| - | < | + | <a name="Degradation"></a><h3>1) Find the genes!</h3> |

| - | <p><i> | + | <p align="justify">We isolated the plasmid containing the <i>dsz</i> genes from a desulfurising environmental isolate of <i>Rhodococcus</i> using a <a href="https://2012.igem.org/Team:Calgary/Notebook/Protocols/plasmidminiprep">modified miniprep procedure</a>. As the native promoter has been shown to be repressed by various sulfur-containing compounds (Li <i>et al</i>., 1996), we designed primers for just the coding sequences of the <i>A, B, </i> and <i>C</i> genes. As these genes all have some illegal cutsites in them we constructed them into the PSB1C3 vector and started our <a href="https://2012.igem.org/Team:Calgary/Notebook/Protocols/mutagenesis">mutagenesis protocol</a>.</p> |

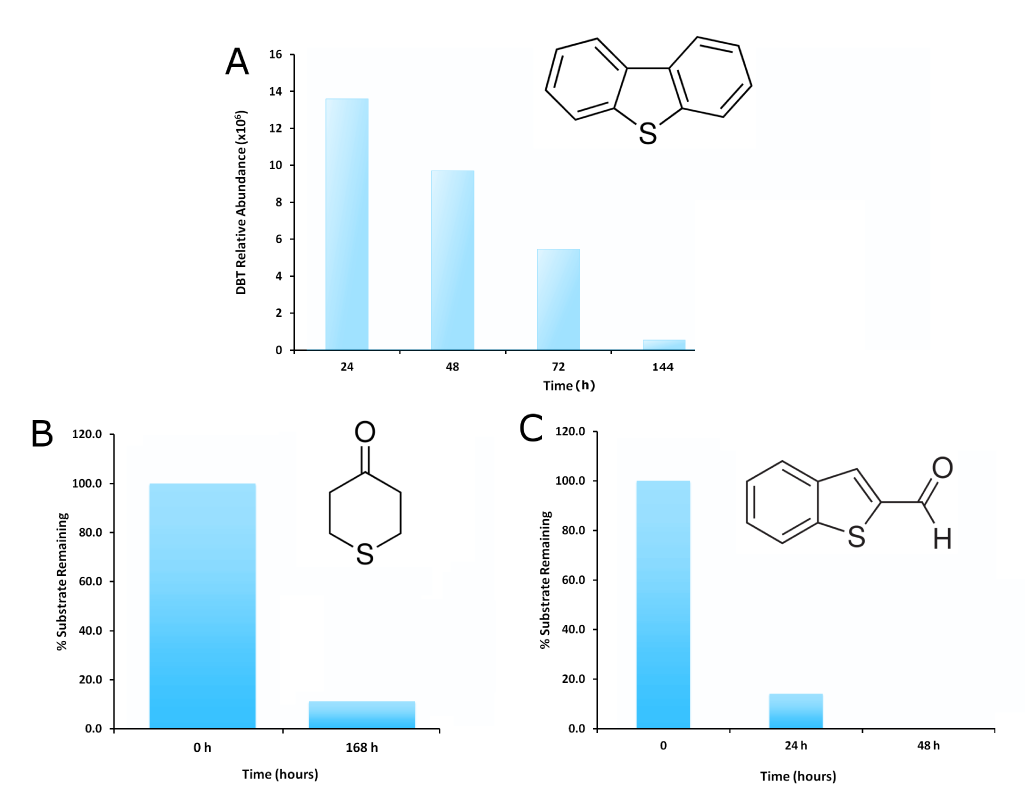

| - | + | <p align="justify"> We performed an experiment to measure the desulfurization rate of select organosulfur compounds by our <i>Rhodococcus</i> strain (Figures 4-6 below). These experiments monitored the degradation of the compounds by our strain over time. We discovered that the <i>dsz</i> operon is capable of desulfurizing a wider range of compounds than just the commonly studied DBT. This shows that this pathway could be a promising solution for degradation of a wide variety of sulfur containing toxins, including those that resemble naphthenic acids. </p> | |

| - | < | + | <p align="justify"></html>[[File:Ucalgary2012 DBTGCMS time points.PNG|center|850px|thumb|Figure 2: <i>Rhodococcus</i> cells were grown in a modified M9 media containing 0.125mM DBT with no sulfur containing compounds (refer to desulfurization assay protocol for details). Samples were taken out at different time points and were run through the GC/MS to detect the amount of DBT. The control only contained modified M9 but no bacteria and it was run through the GC/MS after 6 days of incubation. ]]<html></p> |

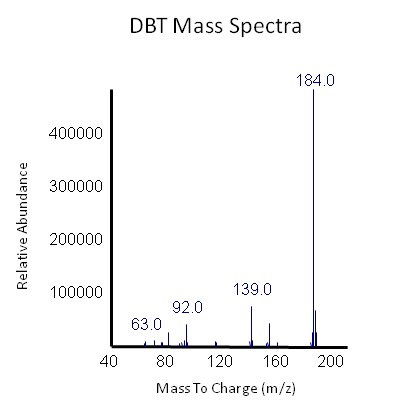

| - | <p> | + | <p align="justify"></html>[[File:Ucalgary2012 DBT GCMS.PNG|center|850px|thumb|Figure 3: The peak in this mass spectrum demonstrates presence of DBT based on its molecular weight of 184 g/mol. This peak is based on the average of our samples at retention time of 13.9 minute (refer to previous graph).]]<html></p> |

| - | + | <p align="justify"> | |

| - | + | </html>[[File:Ucalgary2012-SulfurfigureDBTandothersdegradation.png|center|800px|thumb|Figure 19: <i>Rhodococcus</i> cells were grown in a modified M9 media containing 0.125mM of the indicated compound ('''A:''' dibenzothiophene, '''B:''' tetrahydro-4h-thiopyran-4-one, and '''C:''' benzo[b]thiophene-2-carboxyaldehyde) with no other sulfur containing compounds present in the media (refer to desulfurization assay protocol for details). Samples were taken out at different time points and were run through GCMS to detect the amount of compound remaining. Samples were normalized to a control containing modified M9 but no bacteria, run through the GCMS at the last time point to account for abiotic breakdown. Degradation is seen for DBT as well as other sulfur-containing compounds resembling naphthenic acids, indicating that the pathway may have wider substrate specificity than previously thought.]]<html> | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| + | <h3>2) Mutagenesis: Biobrick Compatability and Increasing DszB Activity </h3> | ||

| + | <p align="justify">In total the <i>dszABC</i> genes had 7 PstI sites and 1 NotI site that needed to be mutated for the biobrick standard. The primers were designed such that the site was removed without the amino acid being changed. In addition, a point mutation of Y63F in DszB increased the activity of the protein (Oshiro <i>et al</i>., 2007), and was included in the mass mutagenesis we undertook. Mutagenesis was performed as described in <a href="https://2012.igem.org/Team:Calgary/Notebook/Protocols/mutagenesis">this protocol.</a></p> | ||

| + | |||

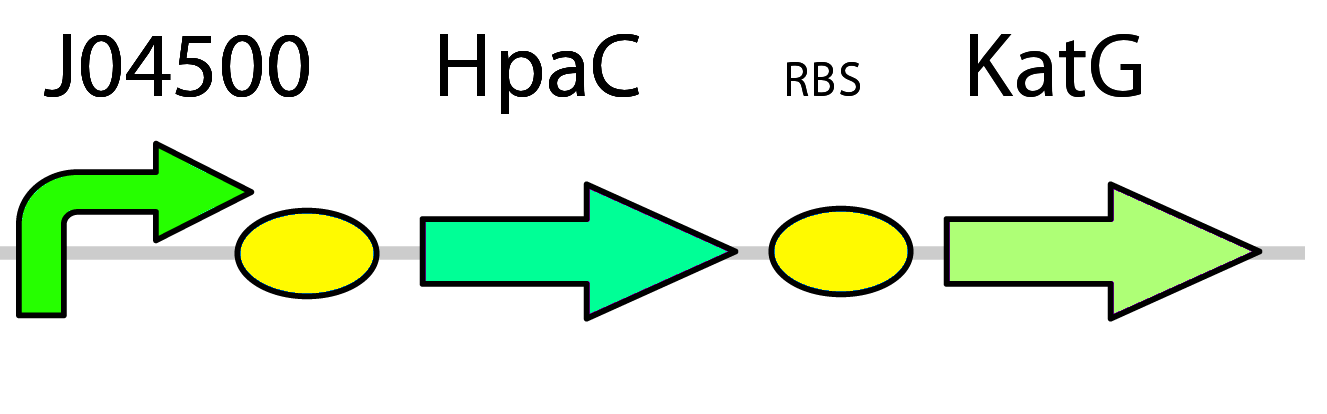

| + | <a name="catalase"></a><h3>3) Replacing DszD with HpaC & Introducing Catalase </h3> | ||

| + | <p align="justify"> | ||

| + | As FMNH<sub>2</sub> is consumed in the first three steps of the pathway it needs to be regenerated or the process will grind to a halt. This usually falls to the <i>dszD</i> gene, however it has been shown that the <i>hpaC</i> gene from <i>E. coli</i> performs the same function more efficiently (Gala´n <i>et al</i>., 2000). One problem arises from this though, as high levels of FMNH<sub>2</sub> cause the production of toxic hydrogen peroxide inside the cell (Gala´n <i>et al</i>. 2000). To address this issue we have included a catalase gene (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K902060"> <i>P<sub>lacI</sub>-katG-LAA</i></a>) that will remove the peroxide that would be toxic to the cell.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p align="justify"></html>[[File:Ucalgary_sulfur_constructs_KatandHpaC.PNG|center|250px|thumb|Figure 7: Diagrammatic representation of the full "optimization circuit", consisting of the oxidoreductase HpaC and a catalase (KatG).]]<html></p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>Results</h3> | ||

| + | <p align="justify">To show that catalase activity increased <i>E. coli</i> survivability in peroxide we cultured the inducible catalase against a catalase-free control with varying levels of peroxide. After growing overnight the negative didn't grow in any culture except in the absence of peroxide, while the catalase cultures could tolerate peroxide. This is shown below.</p><p align="justify"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | </html>[[File:J04500-K137068 KatG assay sulfurucalgary.png|center|600px|thumb|Figure 8: Catalase Assay. Overnight cultures of P<sub>lacI</sub> and P<sub>lacI</sub>-KatGLAA were innoculated into 0 mM, 1 mM, 5 mM, and 10 mM peroxide. Cultures were grown overnight and turbidity was observed. It was found that at 1 mM of peroxide, cultures with just the lacI promotor perished, however when KatG-LAA was expressed, the cells survived.]]<html></p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <p align="justify">To test the action of HpaC to use NADH to recycle FMN into FMNH<sub>2</sub> cell lysates were exposed to NADH and it's absorbance at 340nm (Kamali <i>et al</i>., 2010) was measured over time. Both native HpaC expression and an induced <a href="http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K902058"><i>P<sub>lacI</sub>-RBS-hpaC</i></a> system were tested as well as a negative control. The results are shown below.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p align="justify"> </html> | ||

| + | [[File:Ucalgary2012 HpaC assaycumulativeforthedatapage.png|center|850px|thumb|Figure 9: HpaC Assay with '''A)''' 2 mL cell lysate and '''B)''' 100 µL cell lysate. Cultures of P<sub>lacI</sub>-hpaC and P<sub>lacI</sub>-dszB were grown up overnight in LB with appropriate antibiotics. The following morning, cells were subcultured 1/4 into LB with 200 µM IPTG and allowed to grow for 2h in order to induce protein expression. 1 mL samples of cells were then transferred to 2 mL tubes, washed twice in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and resuspended in this buffer. Samples were then subjected to 5 freeze-thaw cycles in order to lyse cells. After spinning down samples, various amounts of cell lysate were transferred to a cuvette, and a spectrophotometer was blanked at 340 nm with this sample. 140 µM NADH and 20 µM FMN was then added, the cuvette was quickly inverted, and readings were taken at 340 nm. P<sub>lacI</sub>-dszB was used as a control to measure native amounts of oxidoreductase activity, whereas the P<sub>lacI</sub>-hpaC cultures were used to measure activity when HpaC was expressed. The control was just Tris-HCl buffer with the NADH and FMN compounds added. Decrease in absorbance at 340 nm corresponds to the loss of NADH as it is converted to NAD+.]]<html></p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p align="justify">The assay showed that NADH does not abiotically convert into NAD+, however the native expression of HpaC did show a steady decrease in the levels of NADH. The induced overexpression of HpaC caused extremely rapid conversion into NAD+ as reflected by a sharp drop in the absorbance of NADH (see figure B). This drop was much sharper than what was seen when native levels of oxidoreductases were tested, showing that the <a href="http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K902058"><i>P<sub>lacI</sub>-RBS-hpaC</i></a> was functional and that it would effectively recycle FMN.</p> | ||

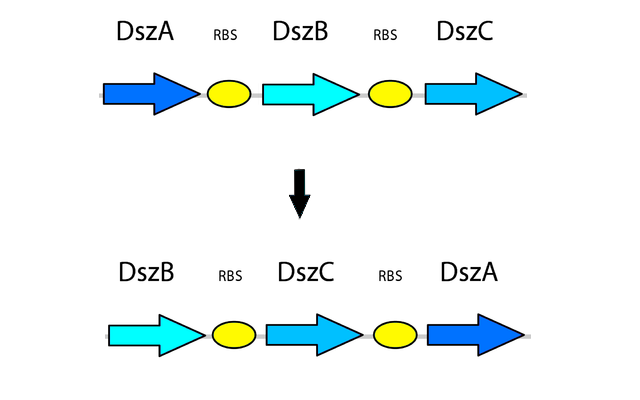

| - | + | <a name="UBC"></a><h3>4) Optimizing Gene Order</h3> | |

| - | + | ||

| - | </html>[[File:DszOperonOptimize.png|center|400px| | + | <p align="justify">Further optimization of the system was achieved through reorganization of the reconstructed operon. Natively the genes are arranged ABC, however the catalytic efficiency of the protein products are 25:1:5 for A:B:C respectively (Li <i>et al</i>., 2008). By rearranging the genes into BCA there is stronger transcription of the weaker proteins, giving a more balanced system overall. These would all be constructed with the same strong ribosomal binding site, <a href="http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_B0034">B0034</a>.</p><p align="justify"> |

| + | |||

| + | </html>[[File:DszOperonOptimize.png|center|400px|thumb|Figure 10: Method of optimizing gene order. The top circuit represents that found natively in the organism, with the bottom circuit representing our modified version.]]<html> | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| + | </a><h2>Final Sulfur Constructs</h2> | ||

| + | <p align="justify">After all of the above considerations are met, four final constructs for our system will be made to allow us to test desulfurization under different conditions.</p><p align="justify"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </html>[[File:WikiConstructs_ucalgary_sulfur_2012_final_systems.png|center|700px|thumb|Figure 11: First set of final constructs for the desulfurization operon, with constitutive Dsz expression and inducible expression of the optimization proteins; either HpaC on its own or coexpressed with KatG]]<html></p> | ||

| - | < | + | <p align="justify"> |

| - | < | + | The first two constructs have the modified <i>dsz</i> operon (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K902052"><i>dszB</i></a>, <a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K804005"><i>dszC</i></a>, <a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K902050"><i>dszA</i></a>) under the control of a constitutive TetR promotor (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_J13002">BBa_J13002</a>) This is to allow for the testing of the optimization circuit, which is under the control of a lacI promotor inducible by IPTG (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_J04500">BBa_J04500</a>). The set-up of these two constructs will therefore allow for the expression of the <i>dsz</i> genes with the ability to test and compare their desulfurization rates <br> A) On their own <br> B) With the addition of <a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K902057"><i>hpaC</i></a> <br> C) With the addition of both <a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K902057"><i>hpaC</i></a> and <a href="http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K137068"><i>katG-LAA</i></a></p> |

| - | < | + | <p align="justify">This will allow us to determine what the optimal construct and expression levels of the additional genes must be in order to have the most effective sulfur removal system.</p> |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| + | </html>[[File:WikiConstructs2 sulfur ucalgary induciblesytems.PNG|center|700px||thumb|Figure 12: Second set of final constructs for the desulfurization operon, with all genes under an IPTG inducible promotor.]]<html> | ||

| + | <p align="justify"> | ||

| + | Due to the large number of proteins being expressed in this system, the possibility of forming inclusion bodies is present. As such, a backup system was built where both the optimization circuit and the <i>dsz</i> operon were under the control of the inducible lacI promoter. This system would allow us to tune the expression of the genes, and determine which expression level is optimal for desulfurization in our bioreactor.</p> | ||

| + | <p align="justify">Currently the final steps of construction of these constructs is underway, following which functionality tests will begin.</p> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

}} | }} | ||

Latest revision as of 01:17, 27 October 2012

Hello! iGEM Calgary's wiki functions best with Javascript enabled, especially for mobile devices. We recommend that you enable Javascript on your device for the best wiki-viewing experience. Thanks!

Desulfurization

Why Remove Sulfur?

Sulfur is the third most abundant element in crude oil (Ma, 2010), and when sulfur containing hydrocarbons are burned they release S02 and S03 gasses into the atmosphere. Not only does this reduce the efficiency and value of our product, but it also contributes to global warming, acid rain, and various health issues due to the pollution (Reichmuth et al., 2000). Strict regulation on sulfur in fuels are now in place and low-sulfur gasoline is mandated across all of Canada (Source: Environment Canada). To upgrade the quality of our fuel we need to remove the sulfur but keep the hydrocarbon backbone.

Our Vision

Though a few pathways for biodesulfurization exist in the microbial world, most involve the destruction of part of the carbon skeleton (an example would be the Kodama pathway)(Soleimani et al., 2007). This would effectively reduce the quality of our product. With this in mind the pathway we have chosen is the 4S pathway found in Rhodococcus spp. It has been characterized and shown to remove sulfur from the model substrate dibenzothiophene (DBT) and convert it to 2-hydroxybiphenyl (2-HBP) in a non-destructive manner. DBT and its derivatives make up 70% of the organic sulfur compounds found in crude oil (Ma 2010), and are also some of the most difficult to remove through chemical means. By using the 4S pathway we will be able to upgrade our fuel and remove recalcitrant compounds at the same time.

4S pathway

Four enzymes are involved in the 4S pathway, 3 of which are directly involved in the conversion of DBT to 2-HBP. Dibenzothiophene monooxygenase (DszC) is responsible for the first two steps of the pathway, converting DBT to DBT-sulfoxide and finally to DBT-sulfone (DBTO2) through the addition of 2 oxygen atoms to the sulfur atom. DBT-sulfone monooxygenase (DszA) then carries out the next step in the pathway, producing 2-hydroxybiphenyl-2-sulfinic acid (HBPS) through addition of a final oxygen to the heteroatom. This causes cleavage of the chemical bonds at the sulfur, breaking the ring and converting the compound from a 3-ring structure to a 2-ring structure. HBPS is then converted to the final product of the 4S pathway by HBPS desulfinase (DszB), producing 2-HBP. At this point, the sulfur has been released from the hydrocarbon in the form of sulfite.

The first three steps of the 4S pathway require FMNH2 and subsequently reduces the reductive power of the cell. WIn order to regain this power an oxidoreductase (DszD) uses NADH to recycle the FMNH2, allowing the reaction to proceed. Without DszD the desulfurization pathway would grind to a halt.

The dszA,B, and C genes form an operon on the pSOX plasmid of R. erythropolis, while dszD is found in the chromosome. Naturally this pathway is slow, however using synthetic biology approaches this process can be optimized.

Our Approach

1) Find the genes!

We isolated the plasmid containing the dsz genes from a desulfurising environmental isolate of Rhodococcus using a modified miniprep procedure. As the native promoter has been shown to be repressed by various sulfur-containing compounds (Li et al., 1996), we designed primers for just the coding sequences of the A, B, and C genes. As these genes all have some illegal cutsites in them we constructed them into the PSB1C3 vector and started our mutagenesis protocol.

We performed an experiment to measure the desulfurization rate of select organosulfur compounds by our Rhodococcus strain (Figures 4-6 below). These experiments monitored the degradation of the compounds by our strain over time. We discovered that the dsz operon is capable of desulfurizing a wider range of compounds than just the commonly studied DBT. This shows that this pathway could be a promising solution for degradation of a wide variety of sulfur containing toxins, including those that resemble naphthenic acids.

2) Mutagenesis: Biobrick Compatability and Increasing DszB Activity

In total the dszABC genes had 7 PstI sites and 1 NotI site that needed to be mutated for the biobrick standard. The primers were designed such that the site was removed without the amino acid being changed. In addition, a point mutation of Y63F in DszB increased the activity of the protein (Oshiro et al., 2007), and was included in the mass mutagenesis we undertook. Mutagenesis was performed as described in this protocol.

3) Replacing DszD with HpaC & Introducing Catalase

As FMNH2 is consumed in the first three steps of the pathway it needs to be regenerated or the process will grind to a halt. This usually falls to the dszD gene, however it has been shown that the hpaC gene from E. coli performs the same function more efficiently (Gala´n et al., 2000). One problem arises from this though, as high levels of FMNH2 cause the production of toxic hydrogen peroxide inside the cell (Gala´n et al. 2000). To address this issue we have included a catalase gene ( PlacI-katG-LAA) that will remove the peroxide that would be toxic to the cell.

Results

To show that catalase activity increased E. coli survivability in peroxide we cultured the inducible catalase against a catalase-free control with varying levels of peroxide. After growing overnight the negative didn't grow in any culture except in the absence of peroxide, while the catalase cultures could tolerate peroxide. This is shown below.

To test the action of HpaC to use NADH to recycle FMN into FMNH2 cell lysates were exposed to NADH and it's absorbance at 340nm (Kamali et al., 2010) was measured over time. Both native HpaC expression and an induced PlacI-RBS-hpaC system were tested as well as a negative control. The results are shown below.

The assay showed that NADH does not abiotically convert into NAD+, however the native expression of HpaC did show a steady decrease in the levels of NADH. The induced overexpression of HpaC caused extremely rapid conversion into NAD+ as reflected by a sharp drop in the absorbance of NADH (see figure B). This drop was much sharper than what was seen when native levels of oxidoreductases were tested, showing that the PlacI-RBS-hpaC was functional and that it would effectively recycle FMN.

4) Optimizing Gene Order

Further optimization of the system was achieved through reorganization of the reconstructed operon. Natively the genes are arranged ABC, however the catalytic efficiency of the protein products are 25:1:5 for A:B:C respectively (Li et al., 2008). By rearranging the genes into BCA there is stronger transcription of the weaker proteins, giving a more balanced system overall. These would all be constructed with the same strong ribosomal binding site, B0034.

Final Sulfur Constructs

After all of the above considerations are met, four final constructs for our system will be made to allow us to test desulfurization under different conditions.

The first two constructs have the modified dsz operon (dszB, dszC, dszA) under the control of a constitutive TetR promotor (BBa_J13002) This is to allow for the testing of the optimization circuit, which is under the control of a lacI promotor inducible by IPTG (BBa_J04500). The set-up of these two constructs will therefore allow for the expression of the dsz genes with the ability to test and compare their desulfurization rates

A) On their own

B) With the addition of hpaC

C) With the addition of both hpaC and katG-LAA

This will allow us to determine what the optimal construct and expression levels of the additional genes must be in order to have the most effective sulfur removal system.

Due to the large number of proteins being expressed in this system, the possibility of forming inclusion bodies is present. As such, a backup system was built where both the optimization circuit and the dsz operon were under the control of the inducible lacI promoter. This system would allow us to tune the expression of the genes, and determine which expression level is optimal for desulfurization in our bioreactor.

Currently the final steps of construction of these constructs is underway, following which functionality tests will begin.

"

"