Team:Goettingen/Notebook/Results

From 2012.igem.org

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

===''motA'' and ''motB''=== | ===''motA'' and ''motB''=== | ||

{| align="right" | {| align="right" | ||

| - | ||[[Image:Fig_motAB.jpg|thumb|300px|right|'''Fig. 5:''' Illustration of the role of the stator proteins MotA and MotB for the flagellar apparatus. A proton gradient at the inner cell membrane causes protons to flow through the stator-”channel”. This flux of protons causes the flagellum to rotate and allows the cells to swim. Each flagellum can harbor around 8-11 stator components. <br>References: <br> Chevance and Hughes (2008) ''Coordinating assembly of a bacterial macromolecular machine.'' Nat Rev Microbiol. 6: 455–465.]] | + | ||[[Image:Fig_motAB.jpg|thumb|300px|right|'''Fig. 5:''' Illustration of the role of the stator proteins MotA and MotB for the flagellar apparatus. A proton gradient at the inner cell membrane causes protons to flow through the stator-”channel”. This flux of protons causes the flagellum to rotate and allows the cells to swim. Each flagellum can harbor around 8-11 stator components. <br>'''References:''' <br> Chevance and Hughes (2008) ''Coordinating assembly of a bacterial macromolecular machine.'' Nat Rev Microbiol. 6: 455–465.]] |

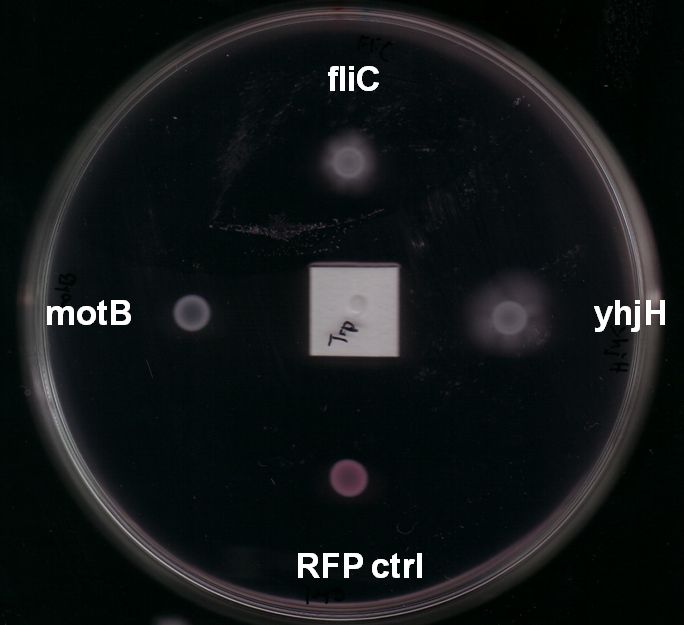

||[[Image:motB_motility.jpg|thumb|300px|right|'''Fig. 6:''' BL21 ''E. coli'' carrying different constructs on LB swimming agar after 12h incubation at 33°C. Cells expressing ''motB'' in puc18 under the natural promoter travelled approximately 0.85cm (radius) and those expressing ''yhjH'' swam around 0.68cm. The empty vector control and motA transformed cells travelled only about 0.5cm.]] | ||[[Image:motB_motility.jpg|thumb|300px|right|'''Fig. 6:''' BL21 ''E. coli'' carrying different constructs on LB swimming agar after 12h incubation at 33°C. Cells expressing ''motB'' in puc18 under the natural promoter travelled approximately 0.85cm (radius) and those expressing ''yhjH'' swam around 0.68cm. The empty vector control and motA transformed cells travelled only about 0.5cm.]] | ||

|} | |} | ||

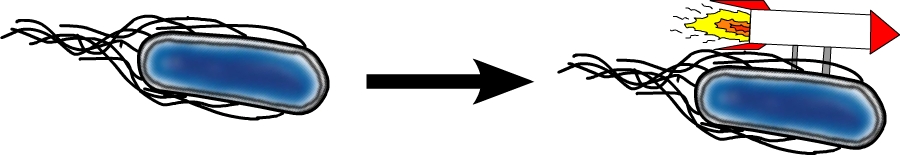

These genes code for proteins that build the stator part of the bacterial flagellum which generates torque by using a proton gradient that exists across the membrane (Fig. 5). Flagellum function depends on copy number of ''motA'' and ''motB'' (Van Way et al. 2000). Therefore we chose to test these genes, hoping that the number of stator protein copies might have a positive effect on motility (Reid et al. 2006). We first tested our strains with ''motA'' and ''motB'' constructs containing the natural 3’ and 5’ regions in puc18 because a strong overexpression might have counterproductive effects. High expressed motA might thereby lead to proton leakage and disturb the metabolism of ''E. coli''. | These genes code for proteins that build the stator part of the bacterial flagellum which generates torque by using a proton gradient that exists across the membrane (Fig. 5). Flagellum function depends on copy number of ''motA'' and ''motB'' (Van Way et al. 2000). Therefore we chose to test these genes, hoping that the number of stator protein copies might have a positive effect on motility (Reid et al. 2006). We first tested our strains with ''motA'' and ''motB'' constructs containing the natural 3’ and 5’ regions in puc18 because a strong overexpression might have counterproductive effects. High expressed motA might thereby lead to proton leakage and disturb the metabolism of ''E. coli''. | ||

| - | + | <br><br> | |

*Results | *Results | ||

**For these two stator-genes it was very hard to get reproducible data. However, after several rounds of testing on different swimming agars and conditions we were able to conclude that overexpression of ''motB'' often had a mild positive effect on motility of BL21 ''E. coli'' (Fig. 6). However, increased expression on ''motA'' seemed to have no or even a slightly negative effect. | **For these two stator-genes it was very hard to get reproducible data. However, after several rounds of testing on different swimming agars and conditions we were able to conclude that overexpression of ''motB'' often had a mild positive effect on motility of BL21 ''E. coli'' (Fig. 6). However, increased expression on ''motA'' seemed to have no or even a slightly negative effect. | ||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

===''yhjH''=== | ===''yhjH''=== | ||

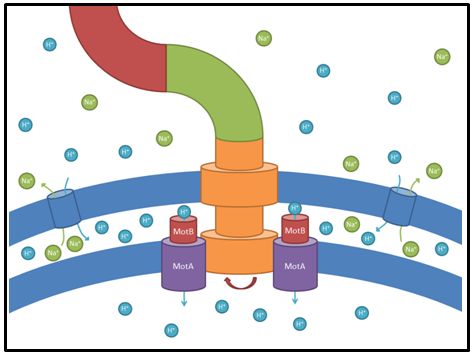

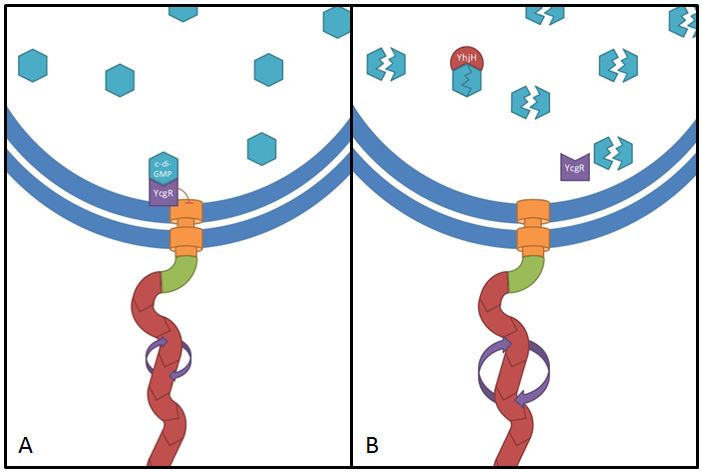

This gene codes for a phosphodiesterase which reduces the levels of c-di-GMP that are involved in cell motility (Ko and Park, 2000). The protein YcgR is able to bind c-di-GMP and act as a flagellar brake which consequently reduces motility (Paul et al. 2010). The mechanism that we would like to exploit is illustrated in Figure 7. Overexpression of ''yhjH'' should therefore result in lower levels of c-di-GMP and increase ''E. coli'''s speed by diminishing the ability of YcgR to act as a brake on the flagellum. The second messenger c-di-GMP furthermore plays a role in the regulation of biofilm development. Expression of ''yhjH'' on the other hand represses biofilm formation (Suzuki et al. 2006) which could also serve our purposes and induce swimming motility. | This gene codes for a phosphodiesterase which reduces the levels of c-di-GMP that are involved in cell motility (Ko and Park, 2000). The protein YcgR is able to bind c-di-GMP and act as a flagellar brake which consequently reduces motility (Paul et al. 2010). The mechanism that we would like to exploit is illustrated in Figure 7. Overexpression of ''yhjH'' should therefore result in lower levels of c-di-GMP and increase ''E. coli'''s speed by diminishing the ability of YcgR to act as a brake on the flagellum. The second messenger c-di-GMP furthermore plays a role in the regulation of biofilm development. Expression of ''yhjH'' on the other hand represses biofilm formation (Suzuki et al. 2006) which could also serve our purposes and induce swimming motility. | ||

| + | {| | ||

| + | ||[[Image:Fig_yhjH.jpg|thumb|500px|'''Fig. 7:''' The ''yhjH'' gene encodes for a c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase. The substrate, c-di-GMP, is a second messenger that binds to YcgR, a protein that functions as a flagellar brake and thus down-regulates the motor (A). We suggest that the overexpression of ''yhjH'' results in increased c-di-GMP degradation and hence in narrowed braking force. Due to a stronger rotation of the flagellum higher motility could be achieved (B).<br> '''References:''' <br> http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P37646; http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P76010]] | ||

| + | ||[[Image:yhjH_motility.jpg|thumb|300px|'''Fig. 8:''' BL21 ''E. coli'' carrying different constructs on [https://2012.igem.org/Team:Goettingen/Project/Materials#Tryptone_swimming_agar Tryptone swimming agar] after 12h incubation at 33°C. Cells expressing yhjH in puc18 under the natural promoter travelled approximately 0.5cm (radius) whereas no swimming could be detected for the control plasmid carrying [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K777125 K777125].]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

*Results: | *Results: | ||

Revision as of 10:35, 26 September 2012

| |

Deutsch  / English / English  |

|

Contents |

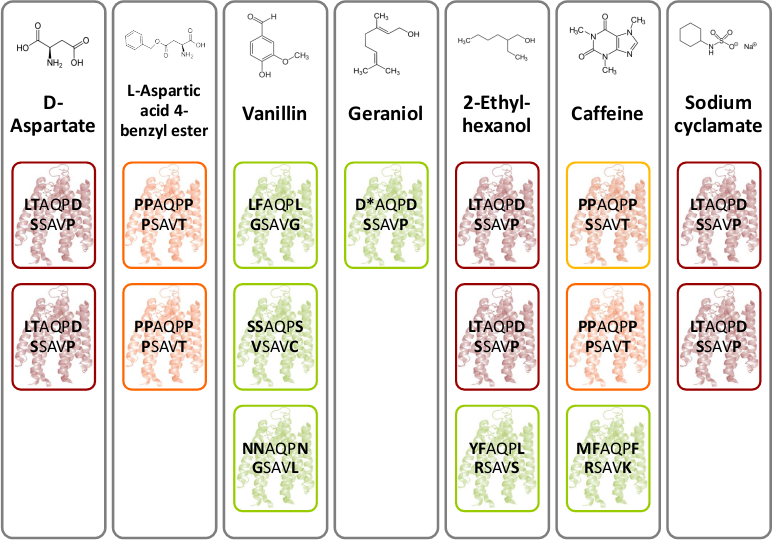

Homing coli: Engineering E. coli to become tracking dogs

The model organism Escherichia coli is naturally capable of sensing substances in its environment and consequently moves directionally towards these, a phenomenon known as chemotaxis. Here, we apply directed evolution to chemoreceptors by targeting five amino acid residues in the ligand binding site to enable E. coli to perceive novel substances. In order to investigate mobility and directed movement towards a substance, an effective mobility selection method using special "swimming plates" is designed. Additionally, we attempt to improve E. coli's swimming velocity by creating new parts derived from its own motility apparatus. Based on our selection system, we identify variants of chemoreceptors with new binding specificities in the mutant library. By these means, we aim to train the bacterium to detect new molecules such as tumor cell markers. Once having established E. coli as our "tracking dog", the possible applications in medicine but also to environmental issues are virtually countless.

#1 - Selection / Swimming

#2 - Speed Improvement

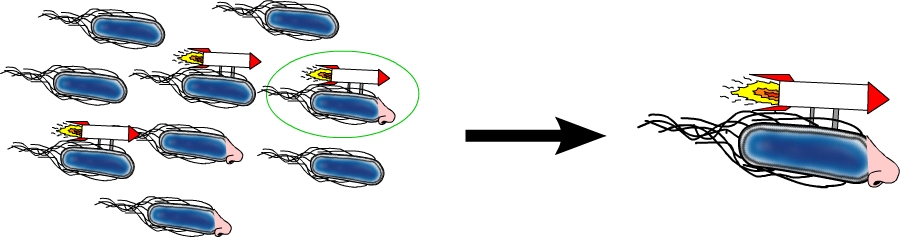

The goal of our group was to enhance the motility of E. coli in order to allow them to reach their targets more efficiently in later applications. This also results in a a faster selection of our Homing Coli and quick generation of results. The BioBricks we designed are therefore primarily directed at flagellum efficiency or number. We selected five different genes that were tested along our project in different strains. E. coli strain BL21 was used as our main object of research because this is a typical lab-strain and therefore usually not very motile. Our goal was to find a way to accelerate BL21 E. coli by transforming them with our constructs. Here is a overview of the genes we tested and the corresponding results.

motA and motB

These genes code for proteins that build the stator part of the bacterial flagellum which generates torque by using a proton gradient that exists across the membrane (Fig. 5). Flagellum function depends on copy number of motA and motB (Van Way et al. 2000). Therefore we chose to test these genes, hoping that the number of stator protein copies might have a positive effect on motility (Reid et al. 2006). We first tested our strains with motA and motB constructs containing the natural 3’ and 5’ regions in puc18 because a strong overexpression might have counterproductive effects. High expressed motA might thereby lead to proton leakage and disturb the metabolism of E. coli.

- Results

- For these two stator-genes it was very hard to get reproducible data. However, after several rounds of testing on different swimming agars and conditions we were able to conclude that overexpression of motB often had a mild positive effect on motility of BL21 E. coli (Fig. 6). However, increased expression on motA seemed to have no or even a slightly negative effect.

- We did not see very strong effects after testing these two candidates. A possible explanation could be that the number of functional stator elements at one flagellum could not be increased anymore or might just not have a significant impact. Furthermore the expression of motA and motB is usually regulated in concert and if out of balance, their expression might not cause any positive effect for motility. For future projects it might be interesting to test chimeric stator proteins that could harbor higher efficiencies or use other ions for torque generation.

yhjH

This gene codes for a phosphodiesterase which reduces the levels of c-di-GMP that are involved in cell motility (Ko and Park, 2000). The protein YcgR is able to bind c-di-GMP and act as a flagellar brake which consequently reduces motility (Paul et al. 2010). The mechanism that we would like to exploit is illustrated in Figure 7. Overexpression of yhjH should therefore result in lower levels of c-di-GMP and increase E. coli's speed by diminishing the ability of YcgR to act as a brake on the flagellum. The second messenger c-di-GMP furthermore plays a role in the regulation of biofilm development. Expression of yhjH on the other hand represses biofilm formation (Suzuki et al. 2006) which could also serve our purposes and induce swimming motility.

Fig. 7: The yhjH gene encodes for a c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase. The substrate, c-di-GMP, is a second messenger that binds to YcgR, a protein that functions as a flagellar brake and thus down-regulates the motor (A). We suggest that the overexpression of yhjH results in increased c-di-GMP degradation and hence in narrowed braking force. Due to a stronger rotation of the flagellum higher motility could be achieved (B). References: http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P37646; http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P76010 |  Fig. 8: BL21 E. coli carrying different constructs on Tryptone swimming agar after 12h incubation at 33°C. Cells expressing yhjH in puc18 under the natural promoter travelled approximately 0.5cm (radius) whereas no swimming could be detected for the control plasmid carrying [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K777125 K777125]. |

- Results:

- Expression of yhjH under its natural promoter in puc18 increased motility in almost all of our assays on LB or Tryptone swimming agar (Fig. 6 & Fig. 8). Not only were the yhjH expressing strains among the fastest on these swimming agar plates but also usually the first colonies to start swimming. This might be an indicator that indeed biofilm formation was inhibited and the E. coli were able to spread faster. Compared to our other tested constructs we got the most reliable results for yhjH. However the positive effect on motility was not present when we used M9 minimal medium swimming agar. Here, yhjH-transformed cells usually did not show a strong tendency for swimming. This result suggests that the motility-effects of YhjH are somehow nutrient-dependent and therefore depend on the used media.

fliC

Flagellin, the product of the fliC gene is the structural protein that builds up the filament of the bacterial flagellum (Fig. 9). By overexpressing fliC we hope to construct longer flagella which might have a positive impact on swimming speed (Furuo et al. 1997). At the same time we were aware that overlong flagella might cause adverse effects due to an obstructive architecture.

- The fliC gene was amplified from DH10B E. coli genomic DNA and contained four forbidden restriction sites. We had to mutate all these sites via overlap PCR. A description for this method can be found here.

- Results

- Our overlap PCR for the mutation of three PstI and one SpeI sites worked efficiently and fast. The resulting PCR product was not cut by any BioBrick standard 10 enzymes.

- In order to avoid too strong levels of expression we included 1kb of the upstream region for most of the assays to allow a certain level of regulation in the cells. Like yhjH-transformants these strains showed increased motility in almost all of our assays (see Fig. 8). On the minimal medium M9 agar plates they were usually significantly faster and showed swimming motility earlier than any other cells (Fig. 9?). On Tryptone swimming agar they were in general the runner up behind yhjH-transformed E. coli. Unfortunately, we had trouble cloning our fliC constructs into pSB1C3 because of a problem in our reverse primer suffix. When we had located the source of the problem it was too late to send this part to the Registry in time.

flhDC

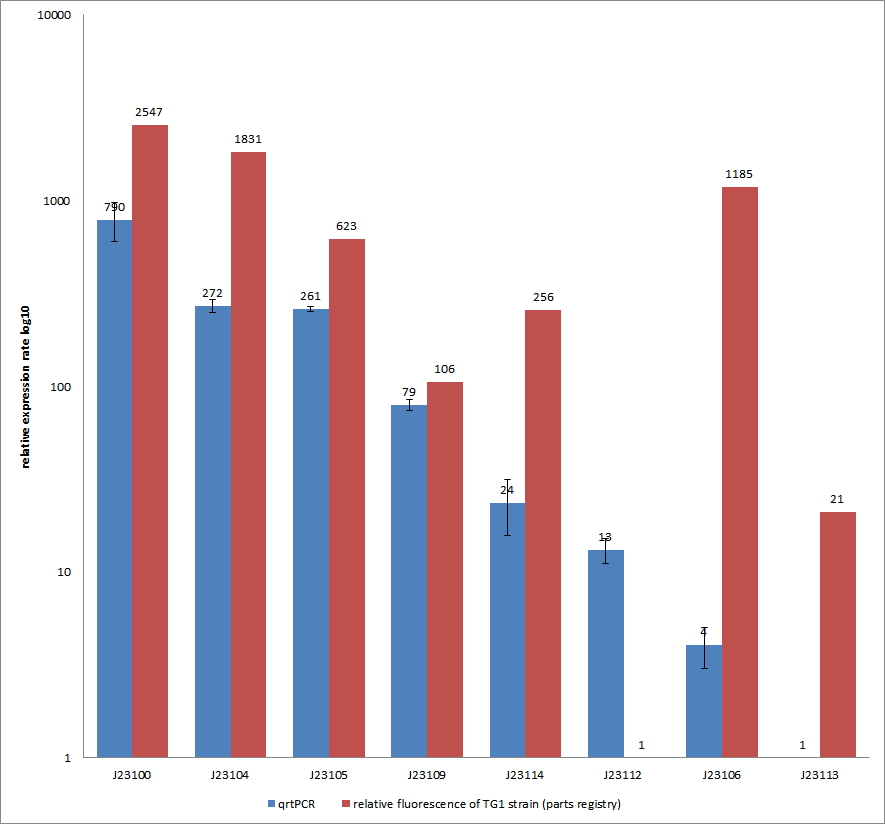

The flhDC operon is the master regulator of motility and chemotaxis in E. coli. This means that it is the main control instance for flagellar synthesis and starts the complex process of flagellar gene synthesis and flagellum assembly (Chevance and Hughes 2008). The flhDC operon codes for the transcriptional regulator FlhD4C2 which forms heterotetramers and activates class II operons in concert with sigma factor 70. Among the gene products of class II operons are several components of the flagellum and the alternative sigma factor FliA which is essential for the transcription of class III genes. It has been shown that increased expression of flhDC also enhances motility in E. coli (Ling et al. 2010). We wanted to see how different levels of flhDC expression affect the speed of our E. coli lab-strains. In theory, the number of assembled flagellums should increase (Fig. 10) and thereby have a positive impact on motility.

- Results

- Our plan was to express flhDC constitutively with a selection of 8 different Anderson-promoters to achieve different levels of transcription. And indeed BL21 E. coli transformed with these constructs showed a higher motility than empty vector controls or WT cells. However, our results were very inconsistent, especially concerning the different promoter strengths when compared to each other. The troubleshooting revealed that we were missing a RBS between the promoters and the ATG within all our constructs. This probably explains the inconsistent results that did not allow us to quantify the effect of our constructs. We hope to finish these experiments with correct constructs soon because we are eager for presentable results!

Electron microscopy

Coming up...

References

- Chevance F. F., Hughes K. T. 2008. Coordinating assembly of a bacterial macromolecular machine. Nat Rev Microbiol. 6: 455–465.

- Furuno, M., T. Atsumi, T. Yamada, S. Kojima, N. Nishioka, I. Kawagishi, and M. Homma. 1997. Characterization of polar-flagellar-length mutants in Vibrio alginolyticus. Microbiology. 66: 3632–3636.

- Ko M., Park C. 2000. Two novel flagellar components and H-NS are involved in the motor function of Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 303: 371-382.

- Ling H., Kang A., Tan M.H., Qi X., Chang M.W. 2010. The absence of the luxS gene Increases swimming motility and flagella synthesis in Escherichia coli K12. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 401: 521-526.

- Paul, K., Nieto, V., Carlquist, W.C., Blair, D.F., Harshey, R.M. The c-di-GMP Binding Protein YcgR Controls Flagellar Motor Direction and Speed to Affect Chemotaxis by a “Backstop Brake” Mechanism. 2012. Mol Cell. 38: 128–139.

- Reid, S. W., M. C. Leake, J. H. Chandler, C. J. Lo, J. P. Armitage, and R. M. Berry. 2006. The maximum number of torque-generating units in the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli is at least 11. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 8066-8071.

- Suzuki, K., Babitzke, P., Kushner, S. R., Romeo, T. 2006. Identification of a novel regulatory protein (CsrD) that targets the global regulatory RNAs CsrB and CsrC for degradation by RNase E. Genes Dev. 20: 2605–2617.

- Van Way, S. M., E. R. Hosking, T. F. Braun, and M. D. Manson. 2000. Mot protein assembly into the bacterial flagellum: a model based on mutational analysis of the motB gene. J. Mol. Biol. 297: 7-24.

#3 - Chemoreceptor Library

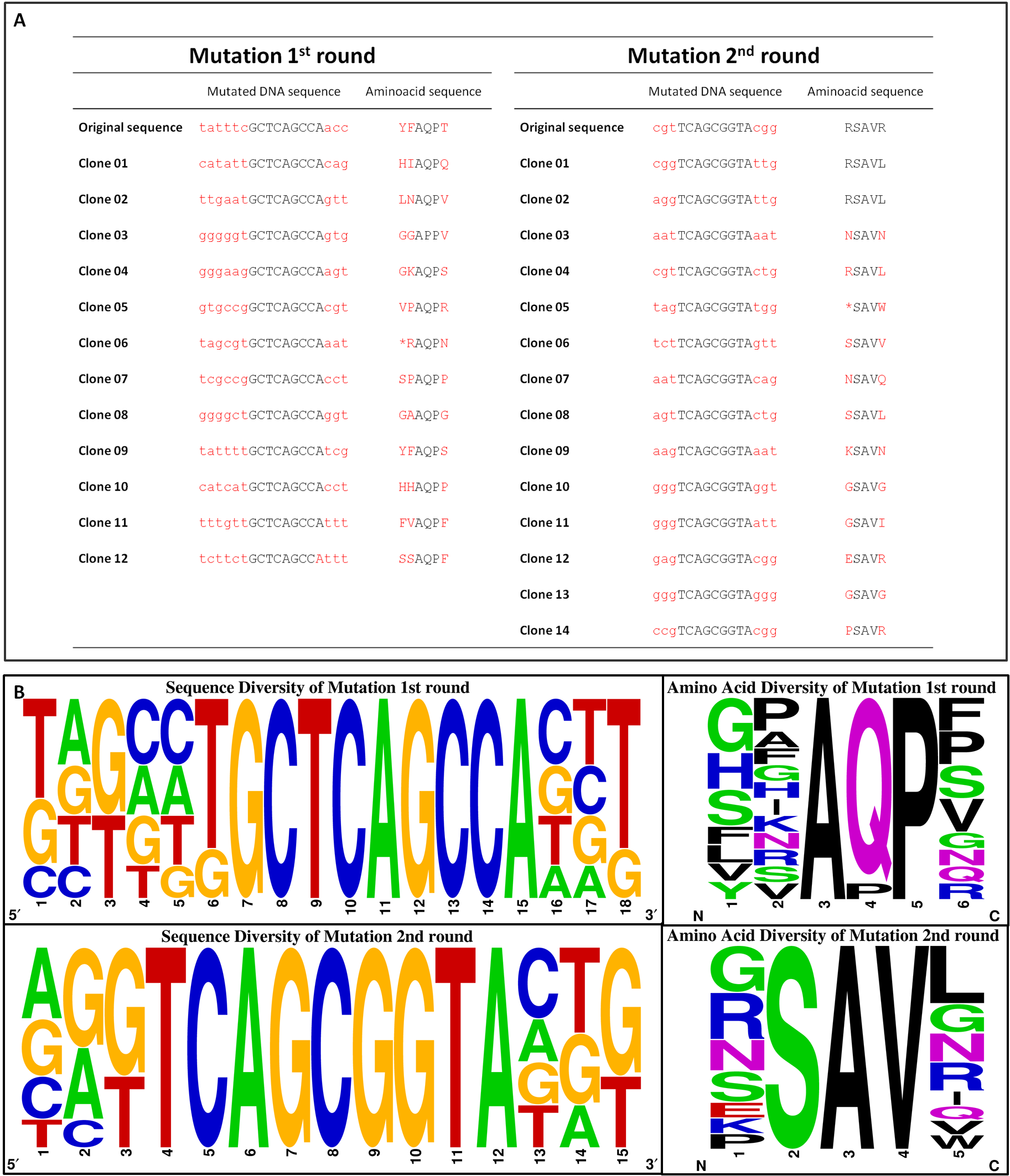

To get rid of BioBrick standard restriction sites, the QuikChange reaction is applied. In the case of the Tar receptor, the BsaI site will be exchanged while keeping the codon for the same amino acid.

To generate a chemoreceptor library our method of choice requires the absence of the BsaI restriction site in both, the insert and the vector backbone, of the cloned plasmid. Therefore, pUC18 containing one BsaI site in the bla gene seems to be not appropriate. Thus, we moved on cloning our promoter constructs with the quik changed Tar (TAR_QC) at the XbaI restriction site into the pSB1C3 BioBrick vector. There are two advantages coming along: Firstly, we need to send our designed biobricks this year in this particular vector and secondly, this vector contains a chloramphenicol resistance gene and hence, lacking the undesired BsaI site.

| ↑ Back to top! |

|

"

"