Team:Paris Bettencourt/Modeling

From 2012.igem.org

Contents |

Overview

Safety is an important issue in synthetic biology, especially on environmental related projects. We already tried to answer the question, “how safe is safe enough?” by involving experts, publics and scientists, and also building biosafety devices. However, to really answer the question, actually we need first to ask ourselves a more basic question, “how do we measure safety?”. As we see synthetic biology as an engineering approach to biology, we could think about adaptation of safety engineering, a well studied engineering subset, that has been widely use to minimize risks on many fields of engineering, such as mechanical engineering, aircrafts, and manufactures. However, the risks they face are surely different from the risks of synthetic biology. Here we propose an approach to assess safety for environmental release of genetically engineered bacteria (GE bacteria).

Background

According to Dana et al1 there are four areas of risk research in environmental application of synthetic biology:

- Differences in the physiology of natural and synthetic organisms will affect how they interact with the surrounding environment,

- Escaped microorganisms have the potential to survive in receiving environments and to compete successfully with non-modified counterparts,

- Synthetic organisms might evolve and adapt quickly, perhaps filling new ecological niches, and

- Gene transfer.

Knowing that there are different areas of risk that we need to take into account, we need to design our safety containment with different parts to deal with each of them. Identifying the relationship between one part and the others will help us to see the reliability of the overall system.

Objectives

- Adapting existing safety assessment tools to synthetic biology.

- Proposing methods to assess safety in synthetic biology.

Methods and Results

We propose a method to assess hazards and risk2 in releasing genetically engineered bacteria to the environment. As a case study, we want to release GE bacteria which will perform some function in the environment and we want to apply 3 sets of bWARE safety containment (alginate beads, bWARE killswitch, semantic containment) to control the hazards and risks. Here we focus more on the reliability of the safety containment system rather than the functional part, although the similar assessment can also be applied to see the functional part reliability.

Hazards Identification

Identifying hazards means that we need to find and understand the possible harm that may happen in the application of our system. Generally there are two potential hazard in environmental application of synthetic biology1 which are the success escape of the GE bacteria followed by a success competition with the natural strain and the horizontal gene transfer.

Risk Assessment

Risk assessment will give an idea what kind of risk we face in releasing the GEO in the environment and help to design the safety containment. Here we adapted a risk management method in workplaces complying with health and safety law 3.

To-do-list to assess risk in 5 steps:

- Identify the hazards

- Decide who might be harmed and how

- Evaluate the risks and decide on precaution

- Record your findings and implement them

- Review your assessment and update if necessary

Worksheet example:

| What are the hazards? | Who might be harmed and how? | What are we already doing? | What further action is necessary? |

| GE bacteria outcompete natural strains | GE bacteria escaping the containment may outcompete natural strains if they have better fitness, creating natural imbalance | Using harmless strain or strain with low fitness compared to natural strain (standard E coli for lab) | Designing a safety containment to prevent the cells reproducing themselves at some point and/or separating them from natural strains |

| Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) | Other strain/species may uptake engineered gene, and if the gene gives advantage in the fitness, it may outcompete other strain and creating natural imbalance | - | Designing a safety containment to degrade DNA and/or separate the DNA from the environment and/or prevent natural strain having advantages from the DNA |

Control hazards and risks

In this step we decided what control elements we want to put to our system to reduce the risks. We should choose the best suitable control elements depending on the system function and application. As we already know that we want to apply bWARE safety containment, here we describe the role of each safety parts in the risks reduction.

- GE bacteria outcompete natural strains

- In order to prevent the success escape of GE bacteria and outcompete the natural strains, we will stop their reproduction by putting a self killing mechanism to kill the cells after they perform the function.

- In case of the failure of the killing mechanism, we will put the cells inside a physical containment so there will be no physical interaction between them and the surrounding cells.

- HGT

- We will use DNAse to degrade DNA after the cells perform the function so they won’t leave any genetic material behind.

- In case of the failure on inefficiency of the DNAse, the physical containment will still protect the DNA from the environment.

- In case of the leakiness of the physical containment, the DNA has special encryption system with the semantic containment so the receiver cell will not be able to read it.

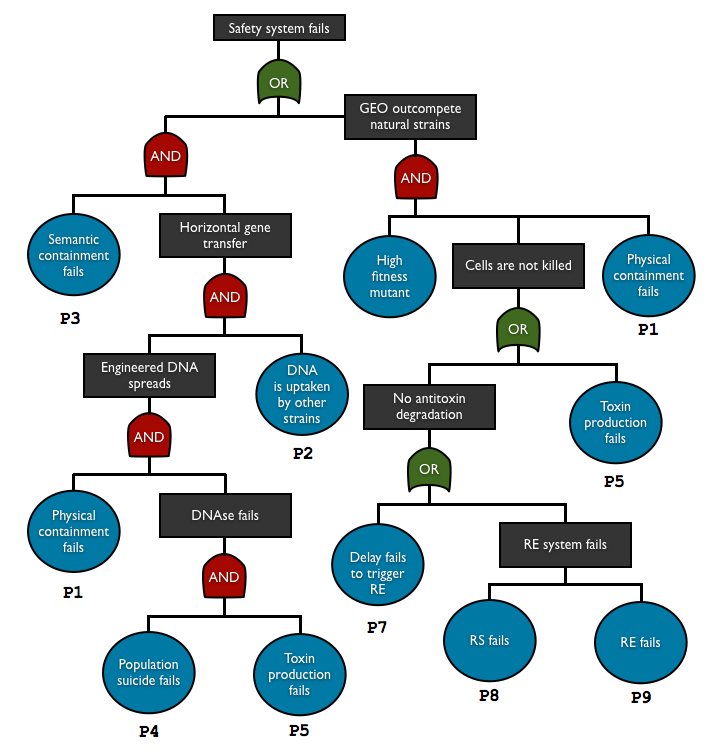

Check controls

To check and predict the reliability of our system, we used fault tree analysis to assess multiple safety containment in one biodevice. This top-down approach allows us to see the relationship between each containment element and predict the overall failure probability. With this method we can see what basic events are the key elements in our system.

AND gate represents independent events

P(A and B) = P(A)P(B)

OR gate corresponds to set of union

P(A or B) = P(A) + P(B)

so the total failure probability of the system is

Ptotal = P1.P2.P3.P4.P5 + P1.P6.(P5+P7+P8+P9)

List of the basic events

| Notation | Failure component | Failure mode | Consequence | Method for determining the probability |

| P1 | physical containment | leakage | DNA/cell escape | experiment |

| P2 | DNA uptake | DNA transferred into natural strain | HGT | transconjugant to donor ratio in HGT is typically <10-5 4 |

| P3 | semantic containment | genetic failure | HGT | estimation* |

| P4 | population suicide | no surrounding cells with enough toxin | no death | based on the cell density and the expectation number of surrounding non-mutant |

| P5 | toxin production | genetic failure | no DNA degradation (w/o antitoxin), no death (with antitoxin) | estimation* |

| P6 | mutant fitness | beneficial mutation | outcompetition of the mutant | estimation* |

| P7 | delay system | genetic failure | no antitoxin degradation | estimation* |

| P8 | restriction enzyme | genetic failure | no antitoxin degradation | estimation* |

| P9 | restriction site | genetic failure | no antitoxin degradation | estimation* |

Genetic failure

There are different processes that lead to a loss of function of a gene

- Mutation

- Recombination

- Plasmid loss

Losing function because of mutation

Estimating the mutation rate which cause failure of the safety containment of the device

- Spontaneous mutation rate of a wild-type E coli strain growing on research medium is 3.3e-9 per nucleotide per generation 5

- approximately ⅔ of nucleotide mutation will change amino acid (64 combination of nucleotides code only 20 amino acids)

- approximately 70% of amino acid change will lose the part function 6

- mean length of genetic coding sequence for E coli (procaryotes) is 924 bp 7 ≈ 1000 bp

So the loss function rate of a gene per generation because of mutation is

PL= 3.3 x 10-9 x ⅔ x 0.70 x 1000 = 1.54 x 10-6

A volume of one alginate bead is approximately 20 uL. So if the cells grow until they reach the stationary phase (4 x 109 cells/ml), we will have 8 x 107 cells. If we started from 100 cells per bead, the number of generations we have is 2log (8 x 107 / 100) =19.6 generations. Therefore the loss function rate of a gene becomes 1.54 x 10-6 x 19.6 = 3 x 10-5.

Recombination

Plasmid loss

According to L Boe 9 plasmid loss rate is defined as the probability that a division of a plasmid-carrying individual results in the birth of one plasmid-free and one plasmid-carrying daughter cell. For the low copy plasmid this rate is about ~1% /division and for high copy plasmid is ~0.01% /division, neglecting the viable/non-viable factor of the cells of losing the plasmid (no selection). If a plasmid with a lost rate of 0.05 is stabilized with a 100% efficient postsegragational killing system, the 5% of the division will result in non viable daughter cell, and we can not see the effect except of increasing the appearing division time by ln 2/ln (1-0.05) = 1.04. Thus in our system we can neglect this plasmid loss assuming that we have antibiotic selection in the beads.

Total failure probability

Discussion

Sean C Sleight et al [1] measured the evolutionary stability of BioBrick-assembled genetic circuits in E coli over multiple generation by measuring the number of loss-functioning mutants. They concluded that to make a robust GEO, one has to take into account 3 principles:

- High expression of genetic circuits comes with the cost of low evolutionary stability (for example induced vs non-induced system)

- Avoid repeated sequences because it will more likely be mutated

- Use of inducible promoters generally increases evolutionary stability compared to constitutive promoters

To predict the robustness of the system from mutation, we have to take into account for how long time (i.e. how many generations) we want our system to work. From their experiment for example, the AHL induced TetR-GFP cells lose their functions after 30 generations, while the uninduced ones lose their function slower (50% after 300 generations).

We need a method to predict the evolutionary stability of circuits from the properties of their parts, but the emergent behaviours of circuits will likely make prediction difficult. Thus it will be very useful if each BioBricks parts is completed with evolutionary stability data sheet, so we can make prediction of the stability of more complex circuits.

References

1 - Genya V Dana et al. Four steps to avoid a synthetic biology disaster. 2012. Nature vol 483

2 - WorkSafe Victoria. A handbook for workplaces, controlling OHS hazards and risks. 2007. Edition No.1

3 - “Five steps to risk assessment” from [http://www.hse.gov.uk/risk/fivesteps.htm http://www.hse.gov.uk/risk/fivesteps.htm]. - risk management method in workplaces complying with health and safety law

4 - Soren J Sorensen et al. 2005. Studying plasmid horizontal gene transfer in situ: a critical review. Nature Reviews Microbiology Vol 3

5 - Heewook Lee et al., Rate and molecular spectrum of spontaneous mutations in the bacterium Escherichia coli as determined by whole-genome sequencing. 2012. PNAS E2774-E2783

6 - Stanley A. Sawyer et al. Prevalence of positive selection among nearly neutral amino acid replacements in Drosophila. 2007. PNAS 104(16):6504-6510

7 - Lin Xu et al. Average gene length is highly conserved in prokaryotes and eukaryotes and diverges only between two kingdoms. 2006. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23(6):1107-1108

9 - L.Boe. 1996. Estimation of Plasmid Loss Rates in Bacterial Populations with a Reference to the Reproducibility of Stability Experiments. Plasmid 36, 161–167. Article No. 0043

"

"

Overview

Overview Delay system

Delay system Semantic containment

Semantic containment Restriction enzyme system

Restriction enzyme system MAGE

MAGE Encapsulation

Encapsulation Synthetic import domain

Synthetic import domain Safety Questions

Safety Questions Safety Assessment

Safety Assessment