Team:Paris Bettencourt/SID

From 2012.igem.org

|

Aim Creation of a novel protein import mechanism in bacteria.

Exploit the natural Colicin import domain fused to any protein at will, dubbed here: "Synthetic Import Domain". Achievements

|

Contents |

Overview

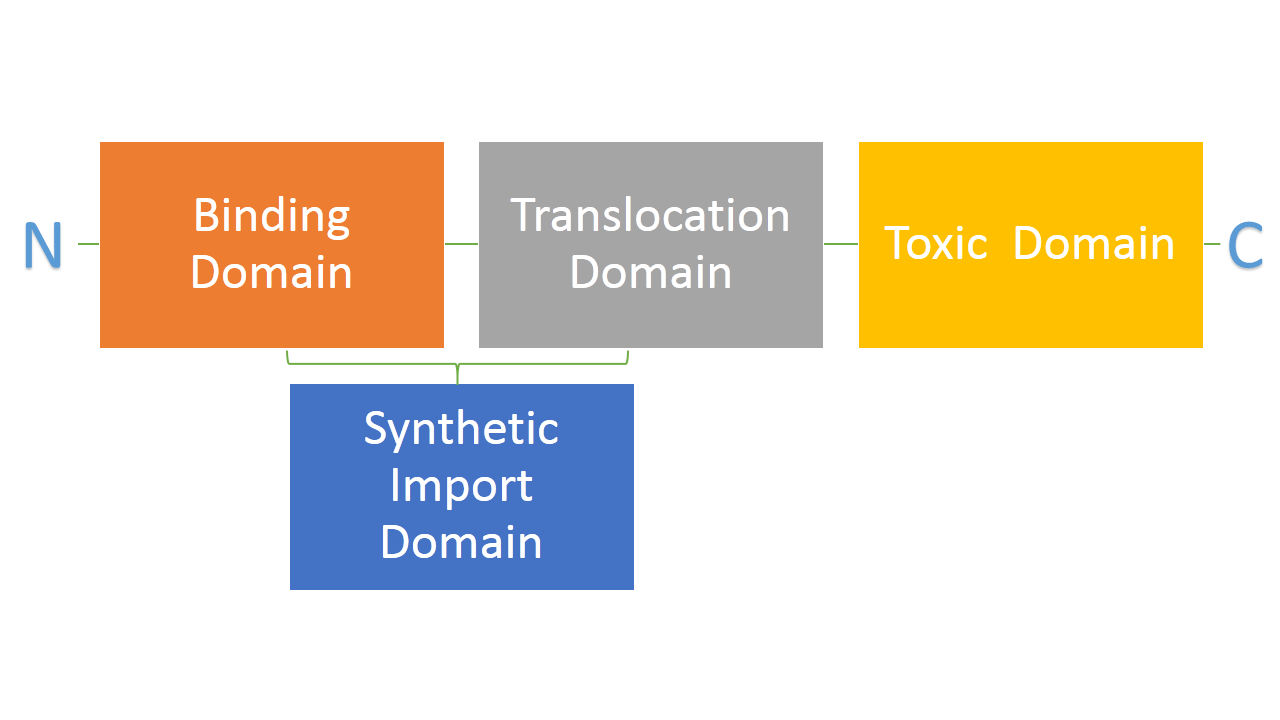

Bacteria developed mechanisms to kill other bacteria in order to reduce competition between themselves in the environment [1]. Some strains of E. coli produce lethal proteins called colicins which kill other bacteria, including E. coli. Colicins are comprised of three main domains which are also a point of difference among many types of colicins. The first domain is responsible for binding to a receptor on a bacterial membrane, the second one is responsible for translocating the protein from outside to inside of bacteria and the third one is responsible for killing bacteria. We are interested in two types of colicins, colicin E2 and colicin D. Both of them use different binding, translocation and killing mechanisms. Colicin E2 is a DNAse and colicin D is an RNAse.

We hypothesize that it is possible to use the binding and translocation part of colicin as a "Synthetic Import Domain" onto which we can fuse other proteins in order to import them into bacteria. This would permit us to create a new communication system between E. coli cells through direct transfer of proteins from one cell to another. Such a system would have a significant impact in biological research and it would be an important addition to tools made by and used by synthetic biology. If we can swap the domains of different colicins, this would greatly expand the possible binding and translocation domains usable in our system, thereby increasing the modularity of our system.

The main aim of this part of the project is to fuse the DNAse domain from colicin E2 to the "Synthetic Import Domain" of colicin D. By doing this we will obtain a toxin that targets different receptor and translocation mechanism than colicin E2 which will increase the variety of toxins we can use and also increase the robustenss of the system. This new toxin could be used in our project as an additional Suicide System.

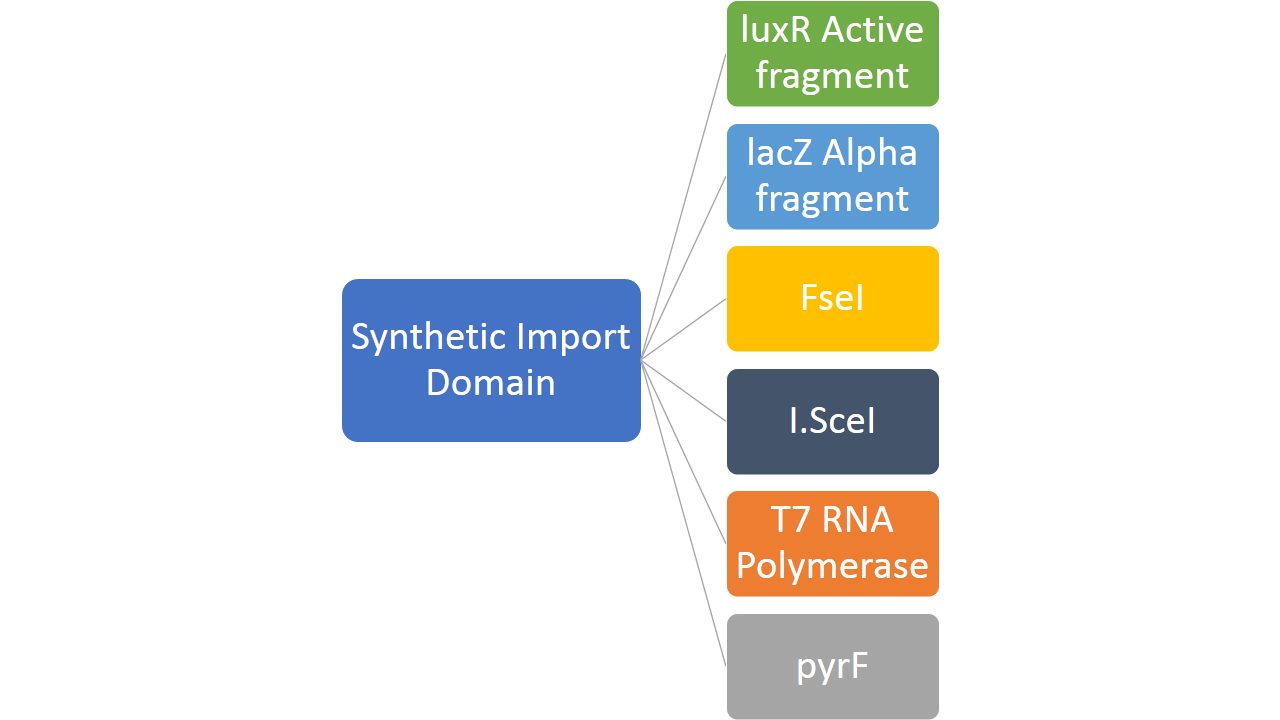

In addition to this, we fused restriction enzymes FseI and I-SceI both to the colicin E2 and colicin D "synthetic import domain". These two enzymes are used in different parts of our project like Restriction Enzyme and MAGE part. By doing this we increased the robustness of our system to mutation because our restriction enzyme can affect the whole population rather than only a single cell.

We also fused a couple of other proteins to easily test the plausibility of our "Synthetic Import Domain" system. So far we built all of the planned constructs and preliminarly tested one of the fused proteins, the lacZα system. The obtained results are promising, and more extensive testing of this system is underway.

Objectives

- Create two types of "Synthetic Import Domains" based on colicin E2 and colicin D binding and translocation mechanisms

- Create new colicin-like toxin by fusing colicin D based "Synthetic Import Domain" with DNAse domain of colicin E2

- Create a generic import system of proteins into bacterial cell by translational fusion. We target proteins like FseI, I-SceI, LuxR active fragment, LacZ alpha fragment, PyrF and T7 RNA polymerase with the two types of "Synthetic Import Domains"

- Test and characterize our novel mechanism of import

Design

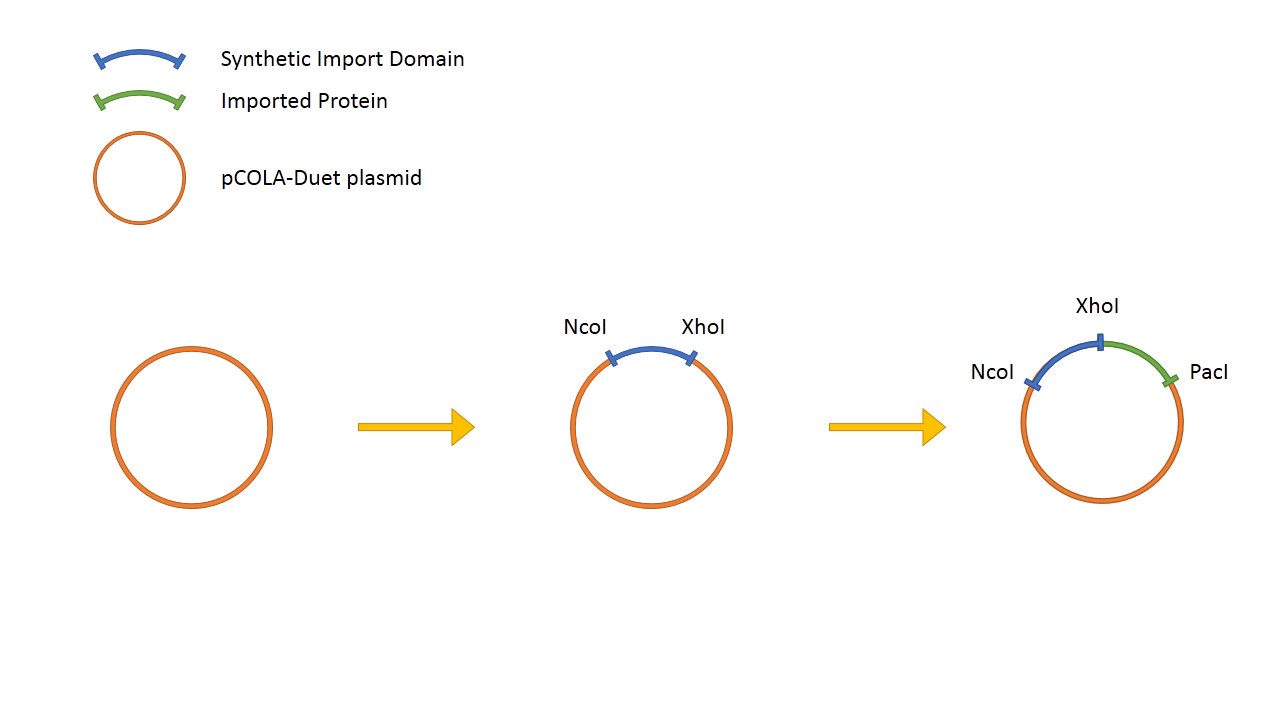

The general design of the Synthetic Import Domain system is very simple. We take the binding and translocation domain from the wild-type colicin and clone it on a plasmid as "Synthetic Import Domain". After, we can fuse any protein of our choice and test if it is going to be imported into other E. coli cells.

Experiments and results

We did not have a chance to thoroughly test our novel system. So far we built all the planned constructs and obtained all the necessary strains for testing our system and doing relevant controls. At this point testing and characterisation of our system is ready to go. We managed to preliminarly test the "Synthetic Import Domain" fused with lacZα protein and get results which point toward success of our system.

Experimental setup

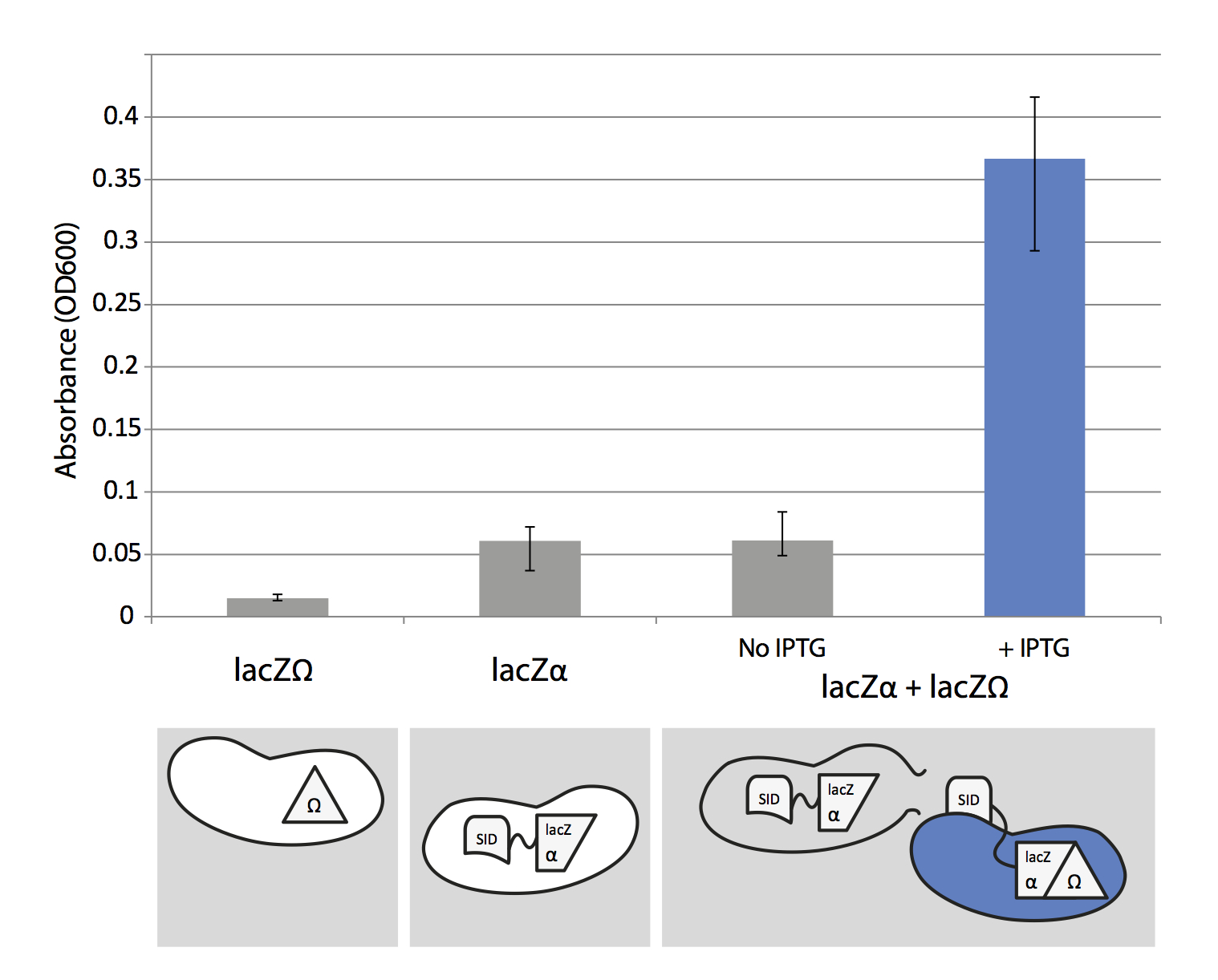

To test lacZα system we used the concept of alpha-complementation. LacZα and lacZΩ are two parts of lacZ protein (β-galactosidase) and the both parts are essential for β-galactosidase functionality. To check its functionality we can add x-gal which turns blue when it's cleaved by β-galactosidase.

The "Synthetic Import Domain" fused with lacZα is cloned into a pCOLADuet™-1 plasmid and is expressed under T7/lac promoter, thus it's IPTG induced. We transformed this plasmid into a T7 expression E. coli strain BL21 (DE3). LacZΩ is located on a chromosome of MG1655+Z1 Δ(lacZ)M15 E. coli strain.

The design of the experiment is quite simple. We grew separately the two strains carrying lacZα and lacZΩ to mid-log phase. Then we mixed them together in two separate reactions, one with IPTG and x-gal, the other with x-gal but without IPTG, and grew them to stationary phase. IPTG induced "Synthetic Import Domain" fused with lacZα is expressed and released into environment when the cell is lysed (mainly because of high expression of T7/lac promoter). Then it binds to and enters the lacZΩ strain because of the "Synthetic Import Domain". In the cell lacZα and lacZΩ protein parts make a functional lacZ protein which cleaves x-gal producing a blue product.

Cells which were not induced by IPTG don't produce lacZα, hence the functional lacZ protein can not be produced and cells do not turn blue. We also separately tested if lacZΩ and IPTG induced lacZα strains produce blue product when x-gal is added.

To measure the amount of produced blue product we lysed the cells in liquid culture with 1% SDS. We centrifuged the culture and measured the absorbance (OD600) of supernatant. The blue product of x-gal cleavage absorbs light around 600nm, similar to the bacteria. For this reason we centrifuge the cells, to prevent their interference with the absorbance measurment of blue product.

Results

Clearly, the amount of blue product produced by mixing lacZΩ and induced lacZα strains is almost six times larger than the mixture with uninduced lacZα and lacZΩ. This result supports our hypothesis that we can use "Synthetic Import Domain" to import other proteins than natural domains of colicins. Nevertheless, this is only a preliminary test and we plan to use more controls and more rigorous experimental design in the future.

Conclusion & Perspectives

The first obvious problem with our experiment is production of blue product in induced lacZα liquid culture. The strain in which plasmid with "Synthetic Import Domain" fused with lacZα was transformed has functional lacZ on its chromosome. We can observe this as a background in our experiment but it makes our system much less "clean". In the future, we will use strains with nonfunctional lacZ as well as the strains with deleted receptor and translocation genes. By doing such controls we will be able to check if our constructs enter the cell or the reaction happens outside of cells.

As stated in the objectives part, we fused several proteins to the "Synthetic Import Domain" and we will use them all to perform experiments that will confirm or refute our main hypothesis. We also plan to transform our constructs into BioBrick standard so that this new import mechanism can be available to the whole iGEM community. This would provide us with a new great tool which could be used not only in synthetic biology but also in biological research in general.

References

- Cascales E, et al. (2007) Colicin biology. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 71:158–229.

"

"

Overview

Overview Delay system

Delay system Semantic containment

Semantic containment Restriction enzyme system

Restriction enzyme system MAGE

MAGE Encapsulation

Encapsulation Synthetic import domain

Synthetic import domain Safety Questions

Safety Questions Safety Assessment

Safety Assessment