Team:Paris Bettencourt/Delay

From 2012.igem.org

Ewintermute (Talk | contribs) (→Characterization of the Yokobayashi et al. sRNA repression device) |

Ewintermute (Talk | contribs) (→Characterization of the Yokobayashi et al. sRNA repression device) |

||

| Line 85: | Line 85: | ||

===Characterization of the Yokobayashi ''et al.'' sRNA repression device=== | ===Characterization of the Yokobayashi ''et al.'' sRNA repression device=== | ||

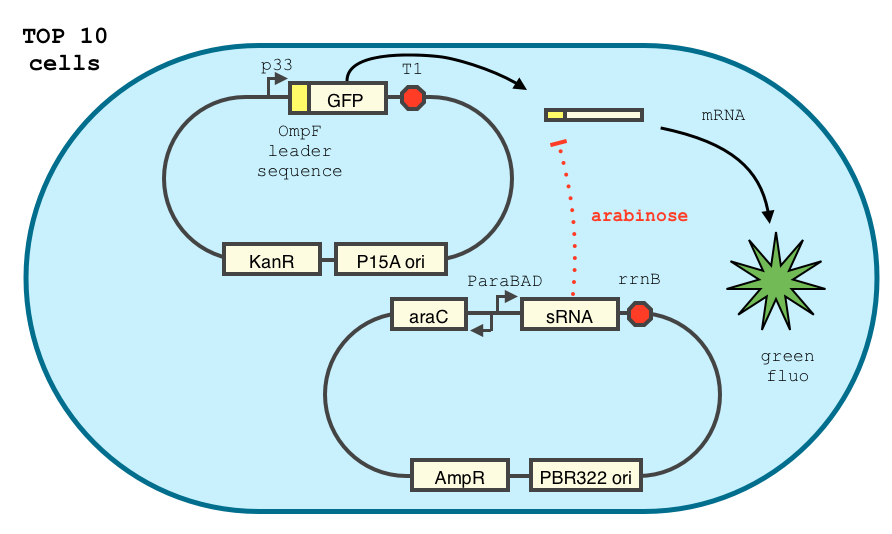

| - | We double transformed TOP10 cells with the GFP and pBAD-sRNA plasmids (see [1] for details, and click [https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2012/c/c4/Odparisbett.png here] for a schematic | + | We double transformed TOP10 cells with the GFP and pBAD-sRNA plasmids (see [1] for details, and click [https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2012/c/c4/Odparisbett.png here] for a network schematic). We chose the this sRNA because it shows a strong repression GFP expression, and binds specifically 5' leader sequence. It does not bind the GFP coding sequence, suggesting is could easily adapted for use with other genes. |

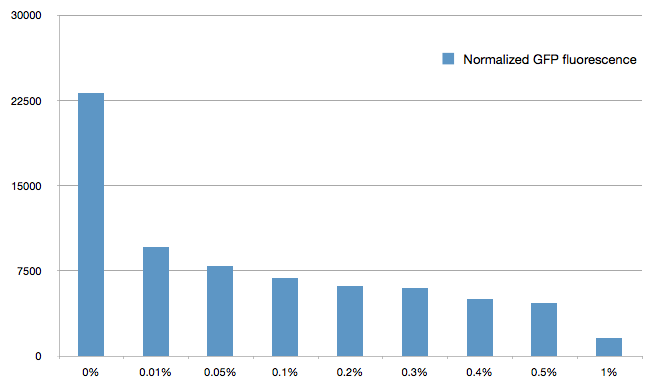

The cells were grown in LB until stationary phase, then diluted 100-fold in LB. After adding defined arabinose concentrations to the medium, we monitored the GFP fluorescence with a TECAN 96-well plate reader. The mean normalized fluorescence after 10 hours is reported below. | The cells were grown in LB until stationary phase, then diluted 100-fold in LB. After adding defined arabinose concentrations to the medium, we monitored the GFP fluorescence with a TECAN 96-well plate reader. The mean normalized fluorescence after 10 hours is reported below. | ||

Revision as of 00:44, 27 September 2012

|

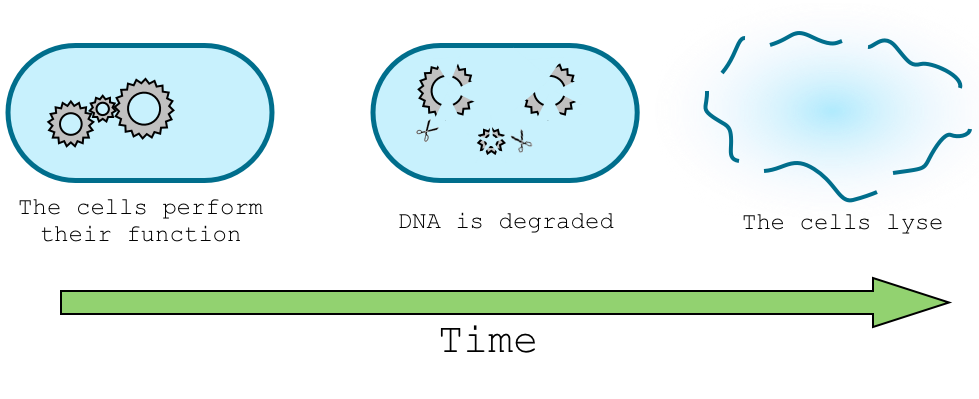

Aim : A programmed delay will allow the cell to perform its intended function before our DNA-degrading suicide machinery is expressed. Experimental system: We used two different approaches to create this delay. The first one is based on the gradual dilution of a regulatory transcription factor. The second one makes use of a stationary-phase specific promoter. Both systems eventually result in the expression of the restriction enzyme I-SceI. In the final design, I-SceI cleaves the antitoxin gene, ultimately dooming the cell. Each step in this causal sequence contributes to the overall delay in the system.

|

Contents |

Overview

The delay system serves to suppress the function of the suicide device and preserve the integrity of the host genome while the organism does its intended job in the environment. We experimented with two designs for producing a programmed delay before the expression of the DNA-degrading suicide machinery.

The dilution delay system relies on the lab-specific expression of a transcriptional inhibitor. This inhibitor is induced by a specific compound found in the laboratory but not in the environment. When the cell enters the environment the inhibitor is gradually degraded or diluted by cell growth. Eventually, the repressor concentration falls below a critical threshold, releasing the suicide machinery.

The sRNA delay system makes use of a stationary-phase specific promoter. Under laboratory conditions, the suicide machinery is repressed by an inducible sRNA. In the environment, the suicide machinery is expressed as soon as the cells reach stationary phase.

Dilution delay system

Objectives

Our cells need time to work in the environment before we degrade their genomes. A programmed delay circuit faces the following challenges:

- The delay must be programmable and long enough for our cells to perform a useful task.

- Once begun, the delay countdown should lead inevitably to death, and should not be reversible.

- Prior to induction, our suicide machinery must be very tightly repressed.

Design

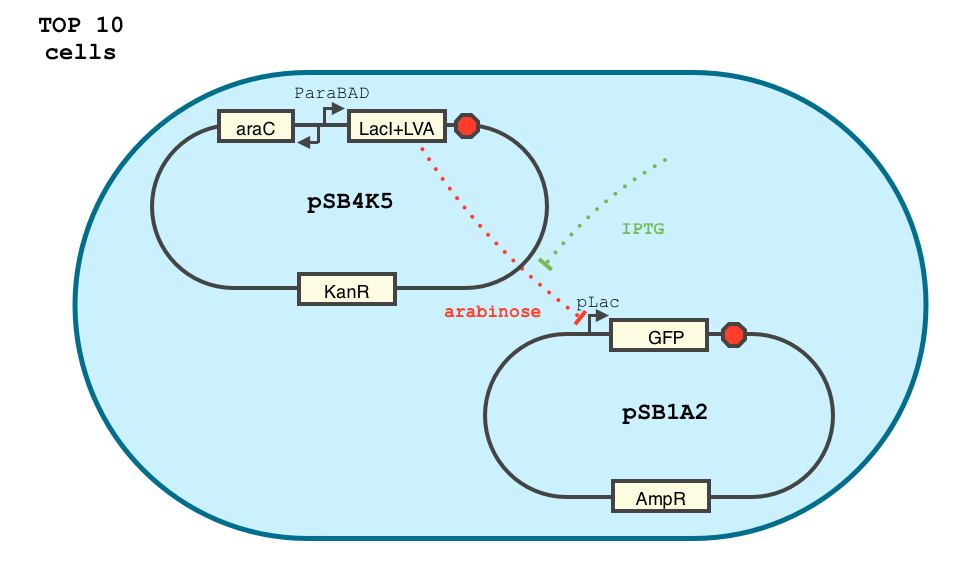

We chose to base our delay on a simple transcriptional network. The arabinose-activated promoter, pBAD, drives the production of the LacI gene. LacI represses a restriction enzyme at the pLac promoter. In the absence or arabinose, the restriction enzyme is eventually expressed, triggering irreversible cell death.

We chose the pLac promoter because of its reputation for tight repression by the lacI protein. Our final design eventually expresses a restriction enzyme, because the DNA hydrolysis reaction is effectively irreversible. But for the purposes of characterization, we substituted GFP for the restriction enzyme at the end of our transcriptional cascade.

The system we created to characterize our delay is shown below:

Characterization

We characterized the behavior of our transcriptional circuit in the presence of IPTG and/or arabinose, or without external inducers (control). GFP expression is induced by IPTG and repressed by arabinose, as expected. By growing the cells in the presence of arabinose and then removing it, we expect to be able to quantify the delay in GFP expression created by our system.

sRNA delay system

Objectives

As an alternative delayed trigger for our suicide machinery we sought to make use of the natural delay experienced by cells as they approach stationary phase. The design requirements for this system are similar to those described above.

- The delay must be programmable and sufficiently long.

- Death must follow inevitably one the countdown begins.

- The suicide machinery is highly toxic, and must not be expressed until needed.

Design

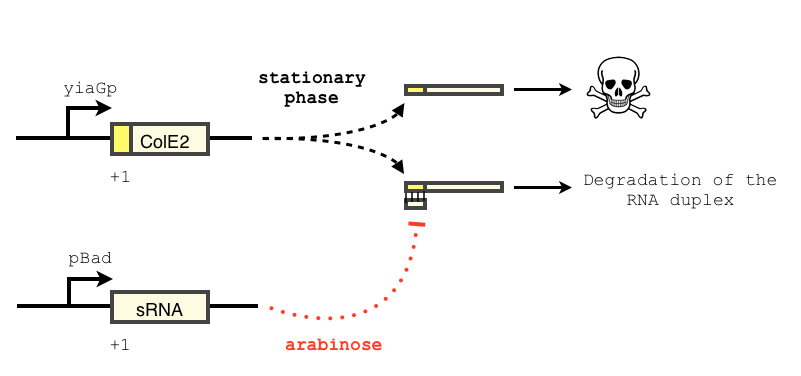

To achieve tight repression, our system is augmented with an sRNA. The concept of our design is described below. Similar systems have been shown to respond in a treshold-linear way [2]

We adapted the construct of Yokobayashi et al. [1] described below.

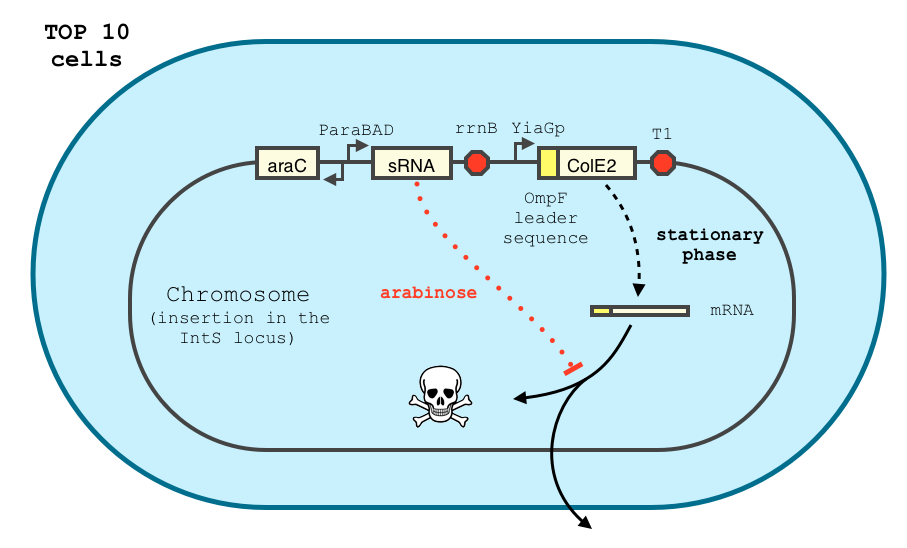

The final design of our construct is shown below.

The transcription of the toxin is controlled twice: first by the stationary phase promoter of yiaG. It is recognized for transcription only by the sigma-S subunit of RNA polymerase, and not the exponential phase sigma-70 subunit. [3], [4].

We have shown that the yiaGp promoter is indeed activated during the stationary phase in our construct, even though the level of trancription is rather low (see experiments)

In order to achieve a complete toxin lockdown, we added a second post-transcriptional repression mechanism. We used and modified the constructs of Yokobayashi et al. to allow a repression of the translation using sRNA [1]. Our specific sRNA binds the leader sequence of its target mRNA and not its coding sequence, and allows a 20 fold repression of protein expression. The transcription of the sRNA is under the control of the pBAD promoter.

We expect the final sRNA delay system will allow the DNA-degradation machinery to be expressed only by cells in stationary phase and lacking arabinose.

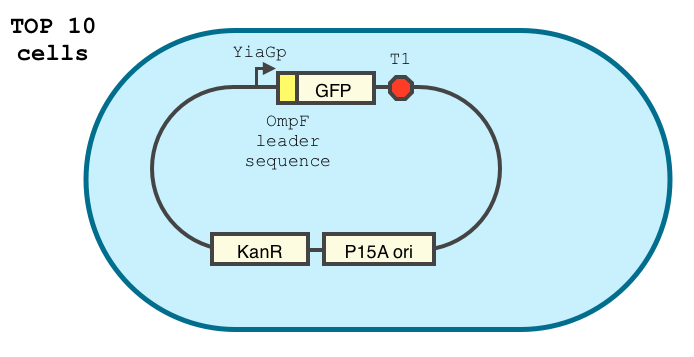

Characterisation of the YiaGp promoter

Using the following construct, we characterized the stationary phase YiaGp promoter in TOP10 cells.

YiaGp is a late stationary phase promoter. It has been shown to be activated by 10 to 30 fold during to stationary phase, and is among the strongest promoters during this phase. Furthermore, its action has been reported to last for a longer time than most stationary phase promoters.

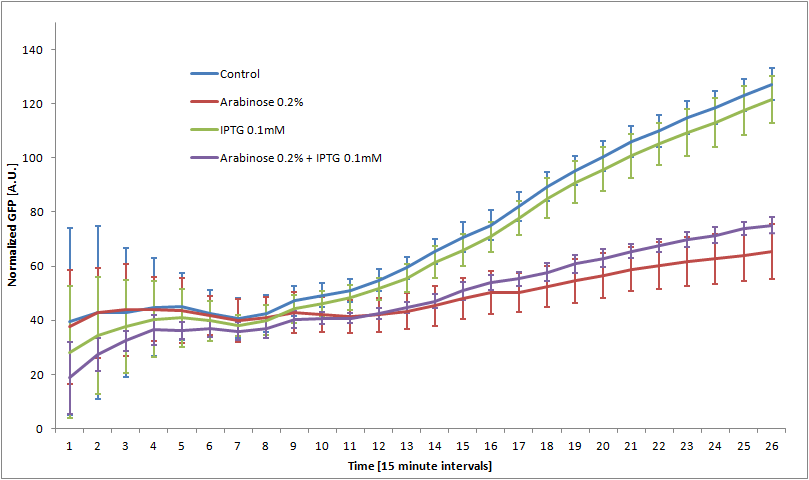

Characterization of the Yokobayashi et al. sRNA repression device

We double transformed TOP10 cells with the GFP and pBAD-sRNA plasmids (see [1] for details, and click here for a network schematic). We chose the this sRNA because it shows a strong repression GFP expression, and binds specifically 5' leader sequence. It does not bind the GFP coding sequence, suggesting is could easily adapted for use with other genes.

The cells were grown in LB until stationary phase, then diluted 100-fold in LB. After adding defined arabinose concentrations to the medium, we monitored the GFP fluorescence with a TECAN 96-well plate reader. The mean normalized fluorescence after 10 hours is reported below.

References

1. Sharma, V., Yamamura, A., & Yokobayashi, Y. (2012). Engineering Artificial Small RNAs for Conditional Gene Silencing in Escherichia coli, 6-13. [http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/sb200001q| Paper]

2. Levine, E., Zhang, Z., Kuhlman, T., & Hwa, T. (2007). Quantitative characteristics of gene regulation by small RNA. PLoS biology, 5(9), e229. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050229 [http://www.plosbiology.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pbio.0050229| Paper]

3. Sharma, U. K., & Chatterji, D. (2010). Transcriptional switching in Escherichia coli during stress and starvation by modulation of sigma activity. FEMS microbiology reviews, 34(5), 646-57. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00223.x[http://jb.asm.org/content/186/21/7112.long| Paper]

4. Shimada, T., Makinoshima, H., Ogawa, Y., Miki, T., Maeda, M., & Ishihama, A. (2004). Classification and Strength Measurement of Stationary-Phase Promoters by Use of a Newly Developed Promoter Cloning Vector, 186(21), 7112-7122. doi:10.1128/JB.186.21.7112 [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00223.x/abstract;jsessionid=8C98B1B383242B9DFF45429802F48428.d02t04| Paper]

"

"

Overview

Overview Delay system

Delay system Semantic containment

Semantic containment Restriction enzyme system

Restriction enzyme system MAGE

MAGE Encapsulation

Encapsulation Synthetic import domain

Synthetic import domain Safety Questions

Safety Questions Safety Assessment

Safety Assessment