Team:NTU-Taida/Project/Fat-Extinguisher

From 2012.igem.org

(→Type 2 Secretion System (T2SS)) |

(→Signal Peptides) |

||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

===Signal Peptides=== | ===Signal Peptides=== | ||

| - | The selection of signal sequence for delivery of specific recombinant proteins is mostly based on empirical data. Some representative signal sequences, such as those of PhoA (alkaline phosphatase), PelB (pectate lysase B), OmpA (outer-membrane protein A), OmpF (outer-membrane protein F), StII (heat-stable enterotoxin 2), or LTB (heat-labile enterotoxin subunit B), are commonly used. We survey papers of successfully secretion of recombinant proteins with specific signal sequences, and choose 3 sequences which were reported to work in the bacterial strains (''E. coli'' DH5α and BL21) we use. They are signal sequences of PhoA [ | + | The selection of signal sequence for delivery of specific recombinant proteins is mostly based on empirical data. Some representative signal sequences, such as those of PhoA (alkaline phosphatase), PelB (pectate lysase B), OmpA (outer-membrane protein A), OmpF (outer-membrane protein F), StII (heat-stable enterotoxin 2), or LTB (heat-labile enterotoxin subunit B), are commonly used. We survey papers of successfully secretion of recombinant proteins with specific signal sequences, and choose 3 sequences which were reported to work in the bacterial strains (''E. coli'' DH5α and BL21) we use. They are signal sequences of PhoA [21], LTB [22], and StII [23], named signal peptide 1 (SP1), signal peptide 2 (SP2), and signal peptide 3 (SP3), respectively. Targeting to the Sec pathway, these signal sequences are cleaved in the periplasmic space, which helps to preserve the structural and functional integrity of the original the peptide. This is also an advantage to choose the T2SS as our delivery system. |

<html> | <html> | ||

Revision as of 03:43, 27 September 2012

Fat Extinguisher

Contents |

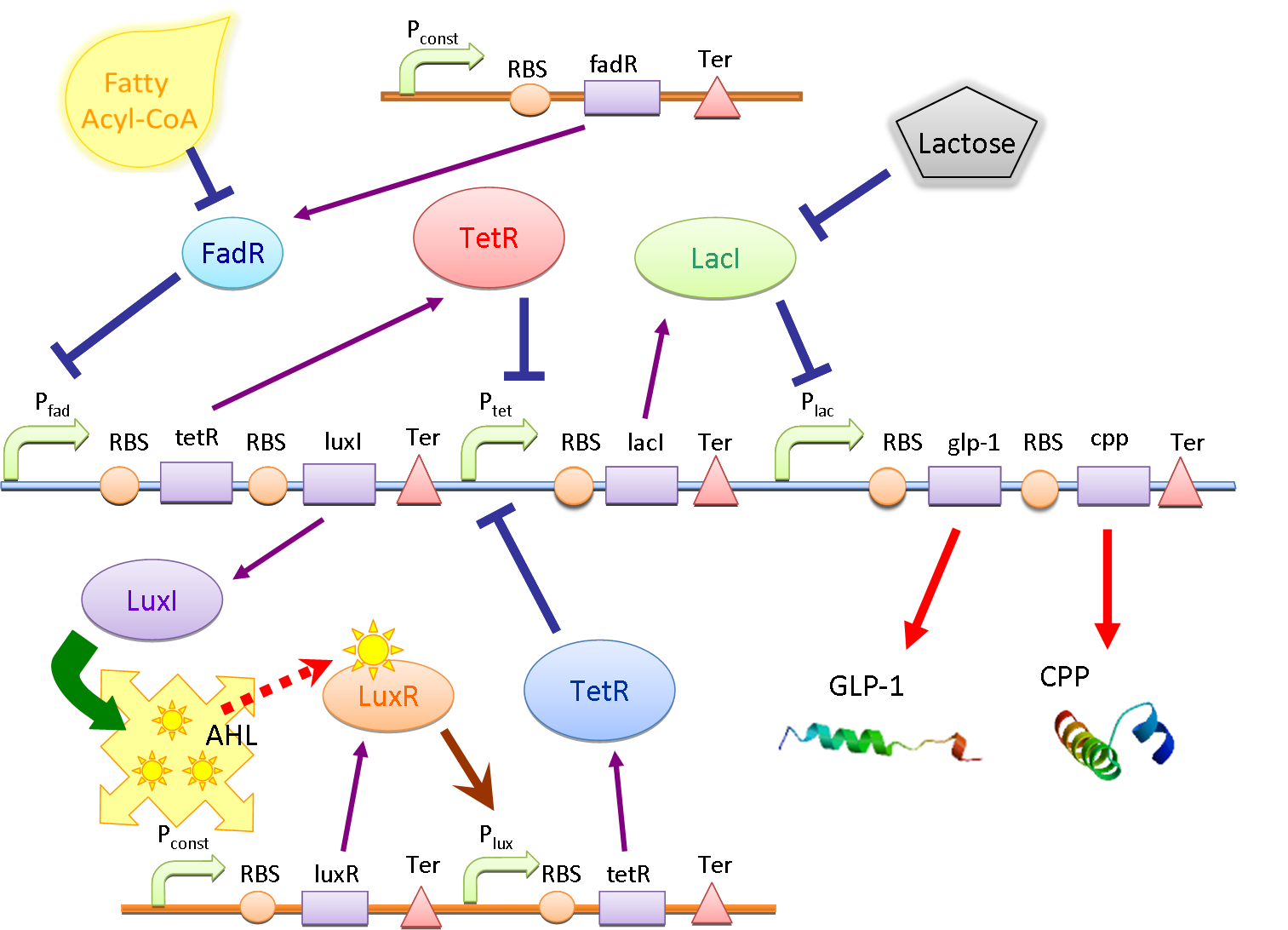

Fatty Acid Biosensor

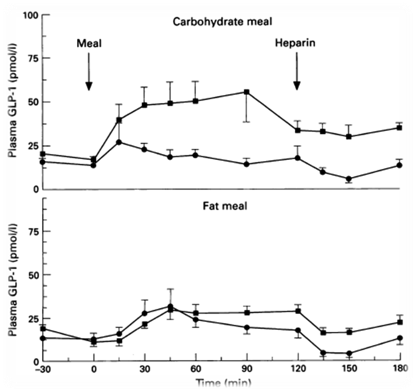

In order to regulate the release of the appetite-regulating neuropeptide GLP-1, we decide to use a fatty acid biosensor which will switch on when the intestinal environment is filled with fatty nutrient. Our team chose fatty acid as a sensor of metabolic states for two main reasons. First, fatty acid is considered as the major cause to obesity because of their highly calorigenic effect. Second, GLP-1 level increases once the blood glucose concentration rises, but there is no significant GLP-1 secretion when the free fatty acid concentration increases in blood stream [1]. Therefore, we hope to compensate this weakness in the appetite regulating mechanisms. By designing the device that secrets GLP-1 on sensing fatty acid around, we aim to make a dietary bacteria.

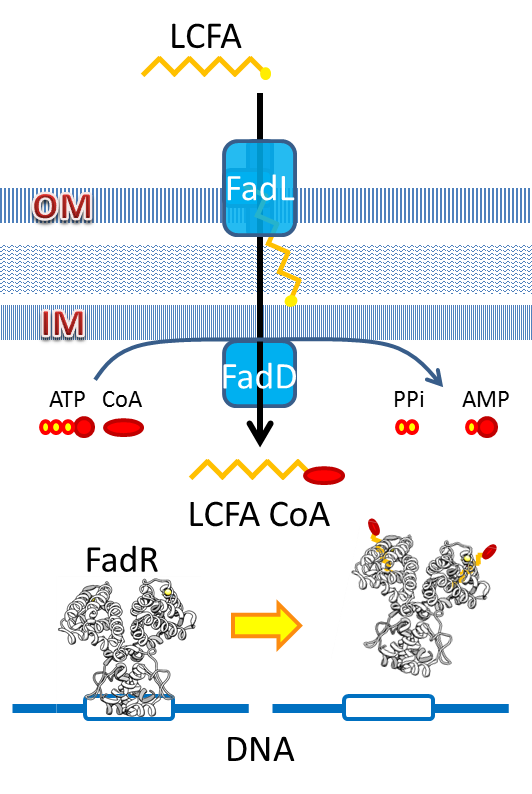

We use the natural fatty acyl-CoA biosensor, the fadBA promoter (PfadBA) from E. coli as the sensor in our design. [2] fadBA is one of the β-oxidation gene which E. coli turns on when the fatty acyl-CoA concentration in the surrounding rises. Therefore, we plan to clone the PfadBA as the promoter in our device, which enables the bacteria to detect fatty acid in the environment.

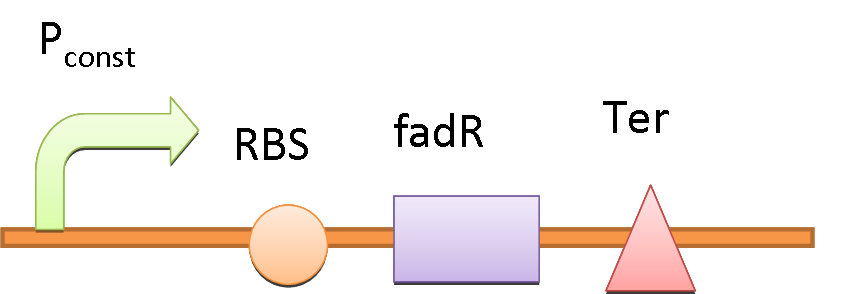

However, the baseline expression of the reportor gene (mRFP) downstream of PfadBA is so high that we cannot see significant signal rise after induction of fatty acid (oleic acid). Therefore, we decide to lower the baseline expression by overexpression of FadR, an endogenous repressor of PfadBA, whose repressive function is antagonized by fatty acyl-CoA. [3] By co-transforming constructs with PfadBA and FadR into the bacterial platform, it is made capable of changing gene expression in response to environmental fatty acid concentration and produce GLP-1 when the host is in taking a meal.

Circuit

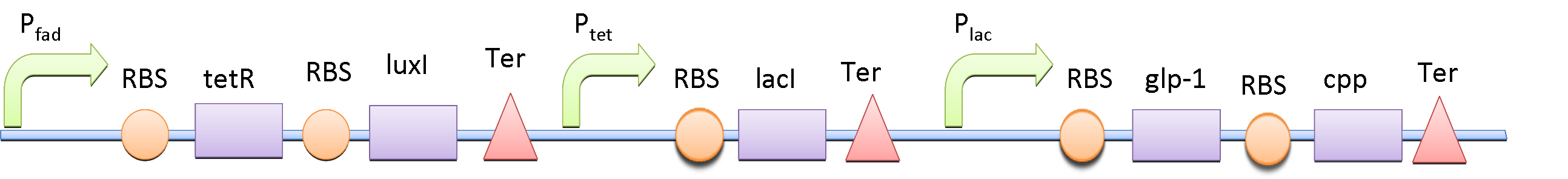

The main circuit is designed to detect the presence of fatty acid in the intestinal environment and produce the peptide drug (GLP-1 in this case) and cell penetrating peptide (CPP) as response. There are two core systems: double repressors and quorum sensing.

Double Repressors

The double repressor system consists of the genes encoded Tet Repressor Protein (tetR) and lac reprresor (lacI). We put tetR downstream of fad promoter (PfadBA) and lacI downstream of tet promoter (Ptet). The DNA sequence encoded GLP-1 and CPP are placed downstream of lac promoter (Plac).

In the absence of fatty acid, a constitutive expressed fatty acid metabolism regulator protein FadR binds to PfadBA, which represses the transcription of tetR and makes Ptet free of TetR. Therefore LacI is expressed, binds to Plac and blocks the production of GLP-1 and CPP. After intake of a fat-rich meal, the fatty acid biosensor FadR is inhibited by the fatty acyl-CoA, which leads to the expression of TetR. The repression of the transcription of lacI by TetR frees the Plac from LacI and leads the final production of GLP-1 and CPP. When there is lactose in the intestinal environment (after drinking milk), the lactose can halt the repression of Plac directly by binding to LacI. GLP-1 and CPP can also be produced in this case.

Quorum Sensing

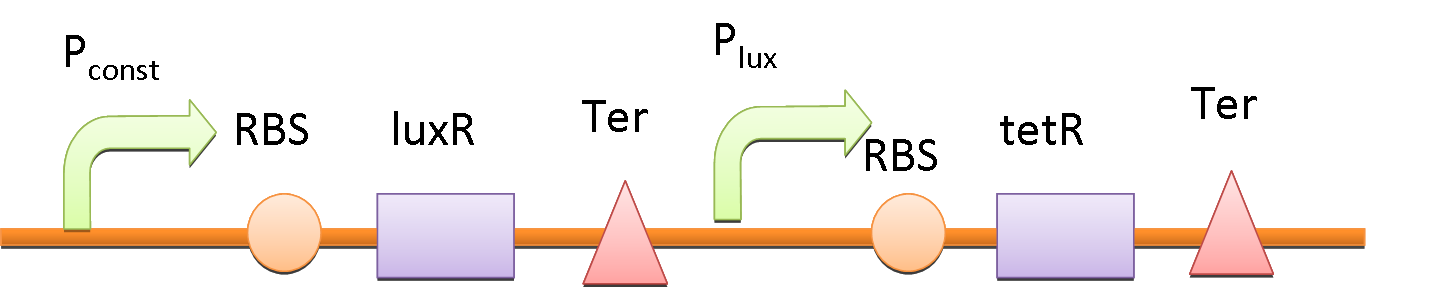

In order to amplify the response and to recruit other bacteria to work together when there are only a few of bacteria sense the fatty acid, a quorum sensing system is also included in our circuit. We place luxI downstream of Pfad and another tetR downstream of lux promoter (Plux). At the same time, the expression of LuxR is constantly driven by a constitutive promoter. When a single bacterium detects the fatty acid, LuxI is expressed and it catalyzes the synthesis of N-Acyl homoserine lactone (AHL). AHL activates the LuxR and binds to Plux, results in extra expression of TetR and amplifies the production of GLP-1 and CPP. AHL can be released into the environment and other bacteria that uptake the AHL can be recruited and start producing GLP-1 and CPP as well.

Appetite Regulating Hormone

Obesity has been regarded as chronic disease recent decades. It is reported that obese people are in a higher risk of type II diabetes, cardiovascular disease and hypertension. Nowadays, there are 1 billion people encountering over-weight problem, and 30 million people are diagnosed of obesity. Modern dietary pattern has been considered the major cause contributing to the phenomena.[5]

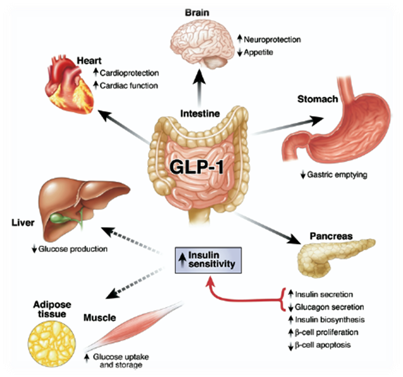

Incretins are a group of gastrointestinal hormones secreted by endocrine cells in small intestine that mainly work to increase insulin levels. Among all the incretins, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is one of the most widely used appetite inhibiting hormone for treating obese patients [6]. In normal physiological condition GLP-1 is secreted by intestinal L cells after a meal, promoting insulin release and inhibit energy intake [7]. The effect on feeding is signaling through G-protein coupled receptor in solitary tract and brainstem [8]. Beside appetite regulating effect, GLP-1 is also well known for its insulinotropic effect, which is useful for treating type II diabetes[9].

We want to generate a device which is not only helps people annoyed by obese problem, but also potentially effective for treating patients with type II diabetes. The half-life of GLP-1 in plasma is pretty short (5 minutes) because of the degradation by DPP-4 peptidase in serum[11], which is one of the reasons why we are thinking about using supplementary GLP-1 to treat obese patients. In addition, previous study has shown that patients with type II diabetes can be treated with delivery of GLP-1 plasmid construct into hepatic cells[12]. Therefore, by applying the similar philosophy to our bacterial device, we are looking forward to building a device that secret GLP-1 into intestinal lumen when the host is replete.

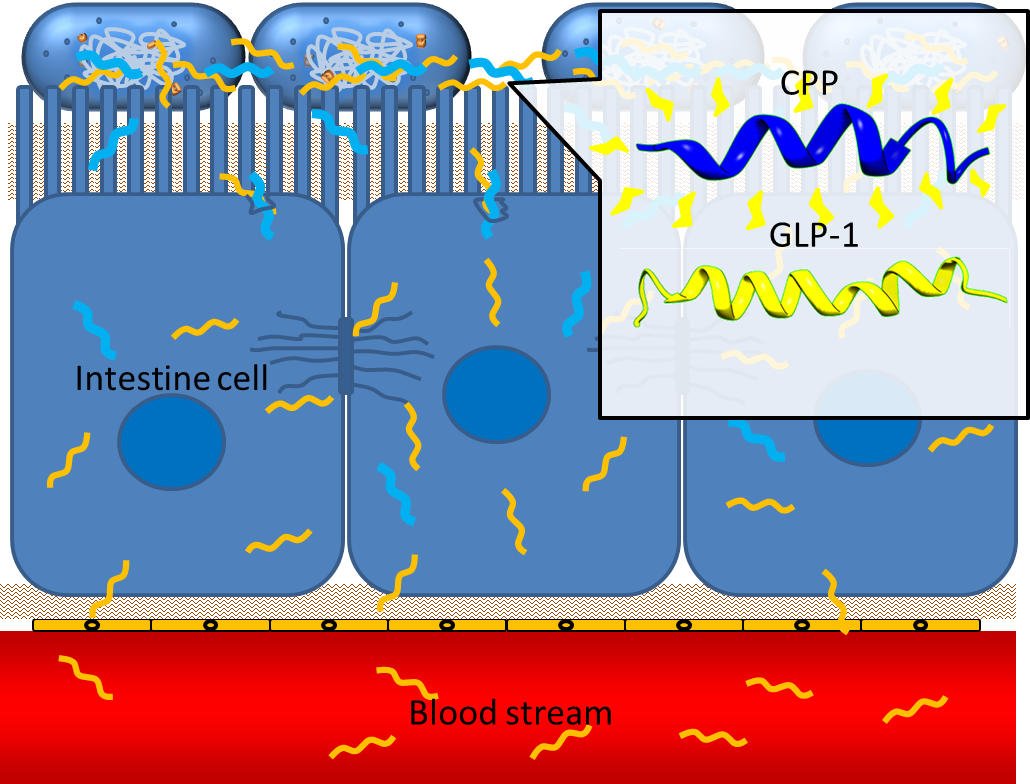

Cell Penetrating Peptide

One obstacle needs to be overcome is the poor penetrating ability of GLP-1 through the intestinal epithelia, since GLP-1 is neither small molecule nor hydrophobic. However, several studies have shown that some short peptides known as cell penetrating peptides (CPPs) can help to deliver biodrugs through intestinal mucosa and increase their bioavailability. [13] CPPs are usually arginine-rich, tend to interact with extracellular matrix and can enhance macropinocytosis of epithelial cells. [14] One recent study even demonstrated that co-administration of GLP-1 and Penetratin, one of the CPPs, greatly increased the intestinal absorption rate to 5%. [15] By applying cell penetrating peptide to our device, we aim to promote the delivery of GLP-1 from intestinal lumen to blood stream, therefore enhance their appetite-regulating effect.

Secretion

In order to achieve the extracellular secretion of our recombinant peptide GLP-1 and CPP, we utilize the endogenous type 2 secretion system (T2SS) in bacteria with specific signal peptides added to the N-terminus of GLP-1 and CPP.

Type 2 Secretion System (T2SS)

Secretion systems of gram-negative bacteria are categorized into 6 types, from type 1 secretion system (T1SS) to type 6 secretion system (T6SS). Among these secretion systems, type 1 and type 2 secretion systems are in charge of transport bacterial protein products into the extracellular space. [16] Here we choose type 2 secretion system (T2SS) as our secretion apparatus which is widely found in gram-negative bacteria, including E. coli. Unlike the single-step secretion of T1SS such as hemolysin transport system (Hly), T2SS has two-step secretion processes. Unfolded or folded proteins with specific signal sequences on their N-terminus are first transported through the inner membrane into the periplasmic space via Sec translocon or twin-arginine translocation (Tat) pathway, respectively. [16, 17, 18] The cleavage of signal peptides is performed by signal peptidase inside the periplasm. Proteins of proper structural features are then transported through the outer membrane into the extracellular space via general secretory pathway (GSP) which consists of 4 distinguished subassemblies: inner membrane platform, outer membrane complex, pseudopilus, and secretion ATPase [19, 20], while small proteins (in our case, short peptides) can also leak from the periplasmic into the environment, regarding the integrity of the outer membrane. Co-expressions of some genes, such as kil, out, tolAIII, and bacteriocin release protein (BRP), were reported to facilitate the extracellular secretory processes. [16]

Signal Peptides

The selection of signal sequence for delivery of specific recombinant proteins is mostly based on empirical data. Some representative signal sequences, such as those of PhoA (alkaline phosphatase), PelB (pectate lysase B), OmpA (outer-membrane protein A), OmpF (outer-membrane protein F), StII (heat-stable enterotoxin 2), or LTB (heat-labile enterotoxin subunit B), are commonly used. We survey papers of successfully secretion of recombinant proteins with specific signal sequences, and choose 3 sequences which were reported to work in the bacterial strains (E. coli DH5α and BL21) we use. They are signal sequences of PhoA [21], LTB [22], and StII [23], named signal peptide 1 (SP1), signal peptide 2 (SP2), and signal peptide 3 (SP3), respectively. Targeting to the Sec pathway, these signal sequences are cleaved in the periplasmic space, which helps to preserve the structural and functional integrity of the original the peptide. This is also an advantage to choose the T2SS as our delivery system.

| Signal Peptide | Source | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| SP1 | PhoA | MKQSTIALALLPLLFTPVTKA |

| SP2 | LTB | MNKVKCYVLFTALLSSLYAHG |

| SP3 | StII | MKKNIAFLLASMFVFSIATNAYA |

Reference

- Attenuated GLP-1 secretion in obesity: cause or consequence?

- Design of a dynamic sensor-regulator system for production of chemicals and fuels derived from fatty acids.

- Unexpected Functional Diversity among FadR Fatty Acid Transcriptional Regulatory Proteins.

- Crystal structure of FadR, a fatty acid-responsive transcription factor with a novel acyl coenzyme A-binding fold.

- Obesity and Overweight.

- The Gut Hormones PYY3-36 and GLP-17-36 amide Reduce Food Intake and Modulate Brain Activity in Appetite Centers in Humans.

- The gastrointestinal tract and the regulation of appetite.

- The Multiple Actions of GLP-1 on the Process of Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion.

- One week's treatment with the long-acting glucagon-like peptide 1 derivative liraglutide (NN2211) markedly improves 24-h glycemia and alpha- and beta-cell function and reduces endogenous glucose release in patients with type 2 diabetes.

- Biology of Incretins: GLP-1 and GIP

- Active glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1): Storage of human plasma and stability over time.

- Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Plasmid Construction and Delivery for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes.

- Oral biodrug delivery using cell-penetrating peptide.

- Cellular Uptake of Arginine-Rich Peptides: Roles for Macropinocytosis and Actin Rearrangement.

- Efficiency of cell-penetrating peptides on the nasal and intestinal absorption of therapeutic peptides and proteins.

- Choi JH, et al. (2004) Secretory and extracellular production of recombinant proteins using Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 64: 625-635

- Muller M, et al. (2005) The Tat pathway in bacteria and chloroplasts. Molecular Membrane Biology 22(1-2): 113-121

- DeLisa MP, et al. (2003) Folding quality control in the export of proteins by the bacterial twin-arginine translocation pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100(10):6115-20

- Korotkov KV, et al. (2012) The type II secretion system: biogenesis, molecular architecture and mechanism. Nat Rev Microbiol 10(5):336-51

- Filloux A (2004) The underlying mechanisms of type II protein secretion. Biochim Biophys Acta 1694(1-3):163-79

- Xu R, et al. (2002) High-level expression and secretion of recombinant mouse endostatin by Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif 24:453-459

- Pillai D, et al. (1996) Production of the beta-subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin in Escherichia coli and its export mediated by the heat-labile enterotoxin chain-B signal sequence. Gene 173(2):271-274

- Dracheva S, et al. (1995) Expression of soluble human interleukin-2 receptor α-chain in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif 6:737-747

"

"