Team:HokkaidoU Japan/Project/Aggregation

From 2012.igem.org

Contents |

Planning of "Aggregation Module"

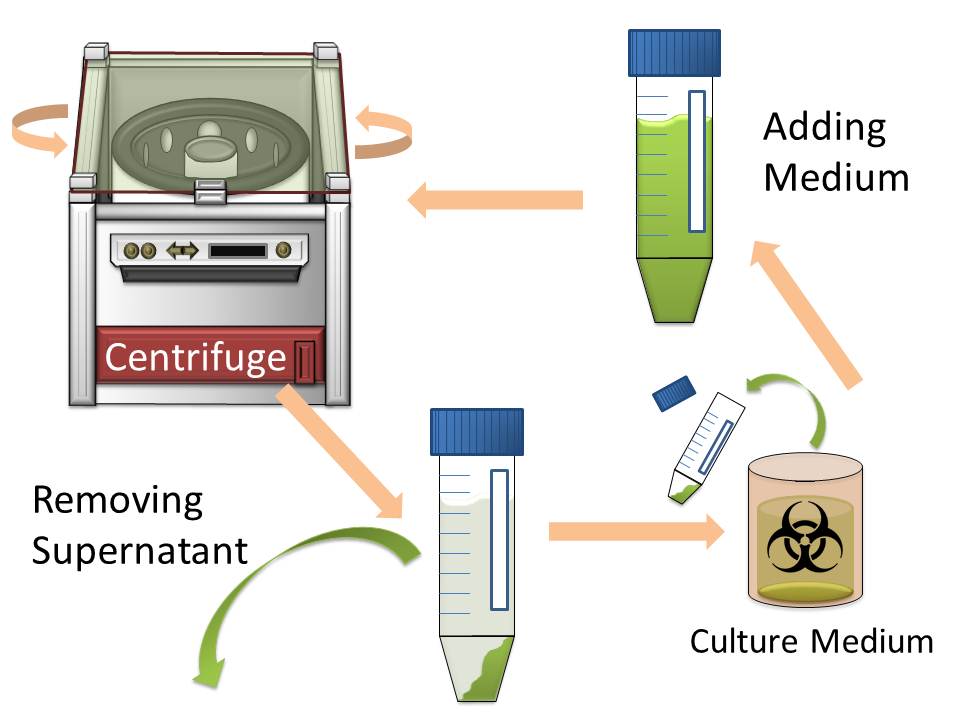

In modern industry, two major methods to harvest cultured cells that produce high-value added macromolecules are centrifugation and filtration. Since sizes of Escherichia coli cells are very small, harvesting them by filtration is difficult. So the most popular method for harvesting E. coli is centrifugation. However centrifugation is time-consuming process particularly when harvest them from large volume of culture medium. (Fig. 1)

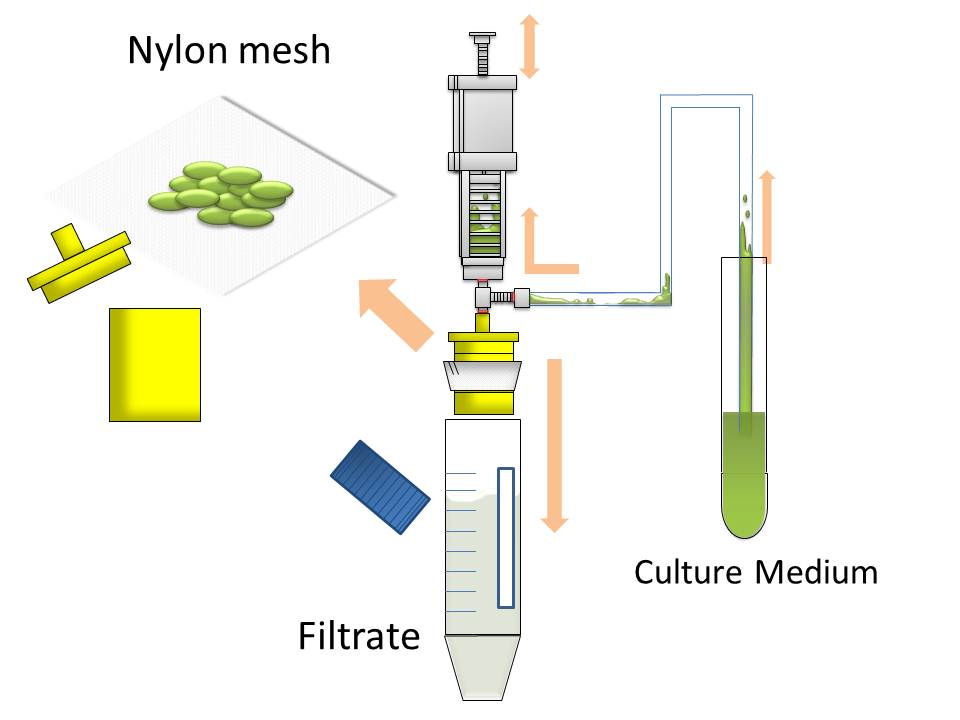

The purpose of this project is to make more efficient method for macromolecule production in bacterial cells by eliminating time-consuming centrifugation step, through enlarging sizes of E. coli cell clusters (large enough to be captured), named “Bio-capsule”, for harvesting them by filtration on nylon mesh.

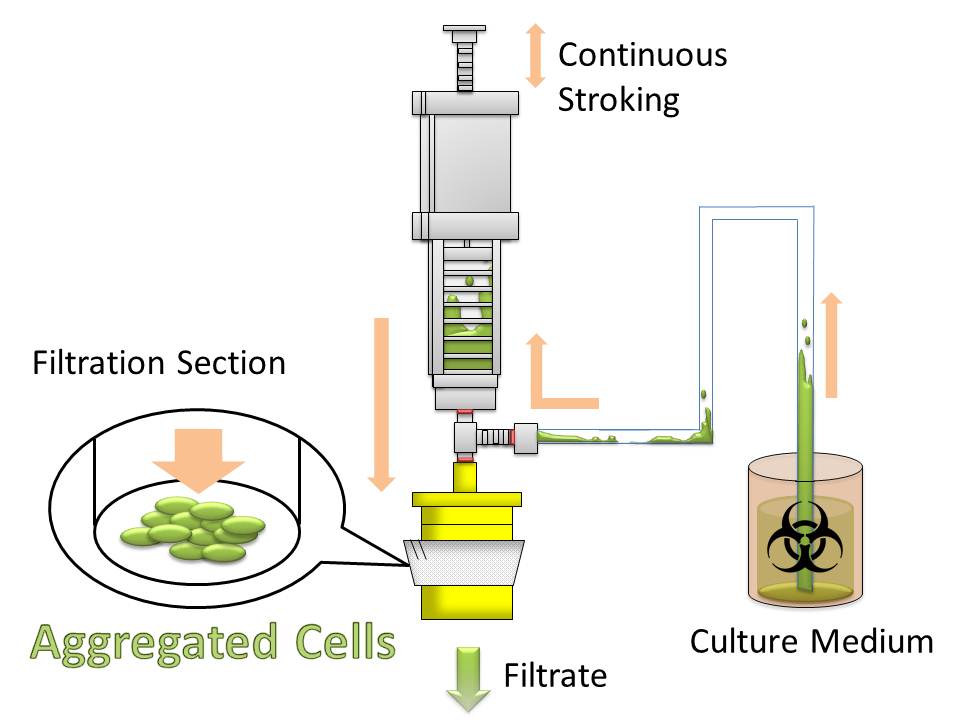

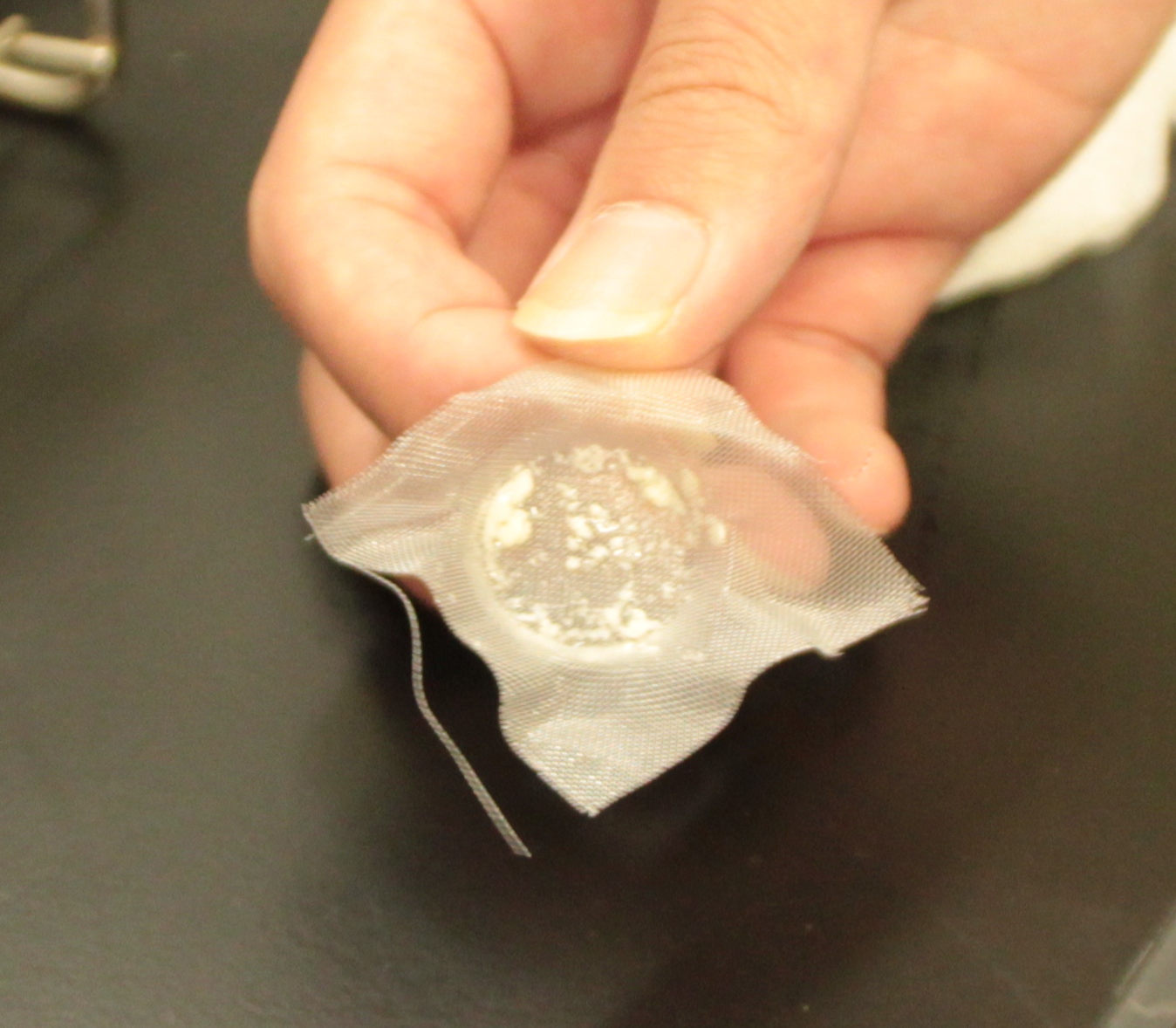

For this purpose, we made E. coli expressing adhesion molecule, Antigen 43 (Ag43), on the surface of outer membrane of it for enhancing cell-cell interaction. We have succeeded in harvesting large amount of E. coli cells as filter cake on nylon mesh after continuous rapid strokes of injector (Fig. 2). The “Bio-capsule” resulted from function of the “Aggregation Module” will contribute to the industrial production in near future.

Background of "Aggregation Module"

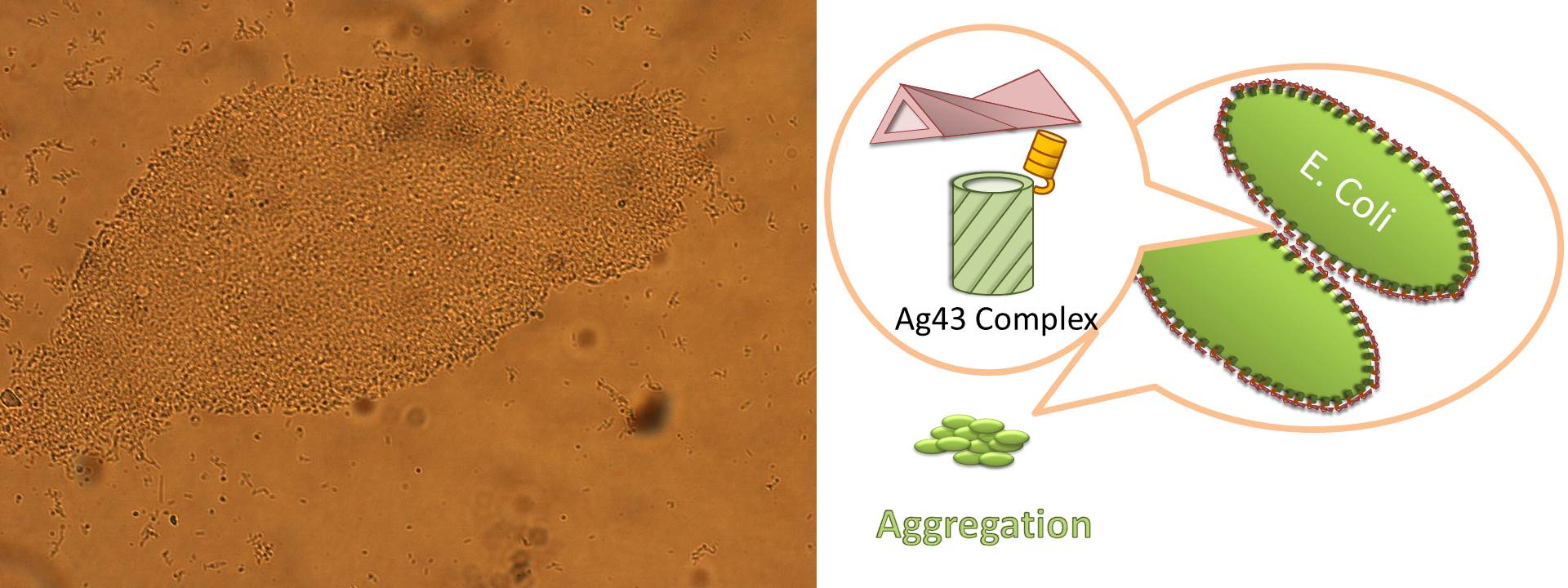

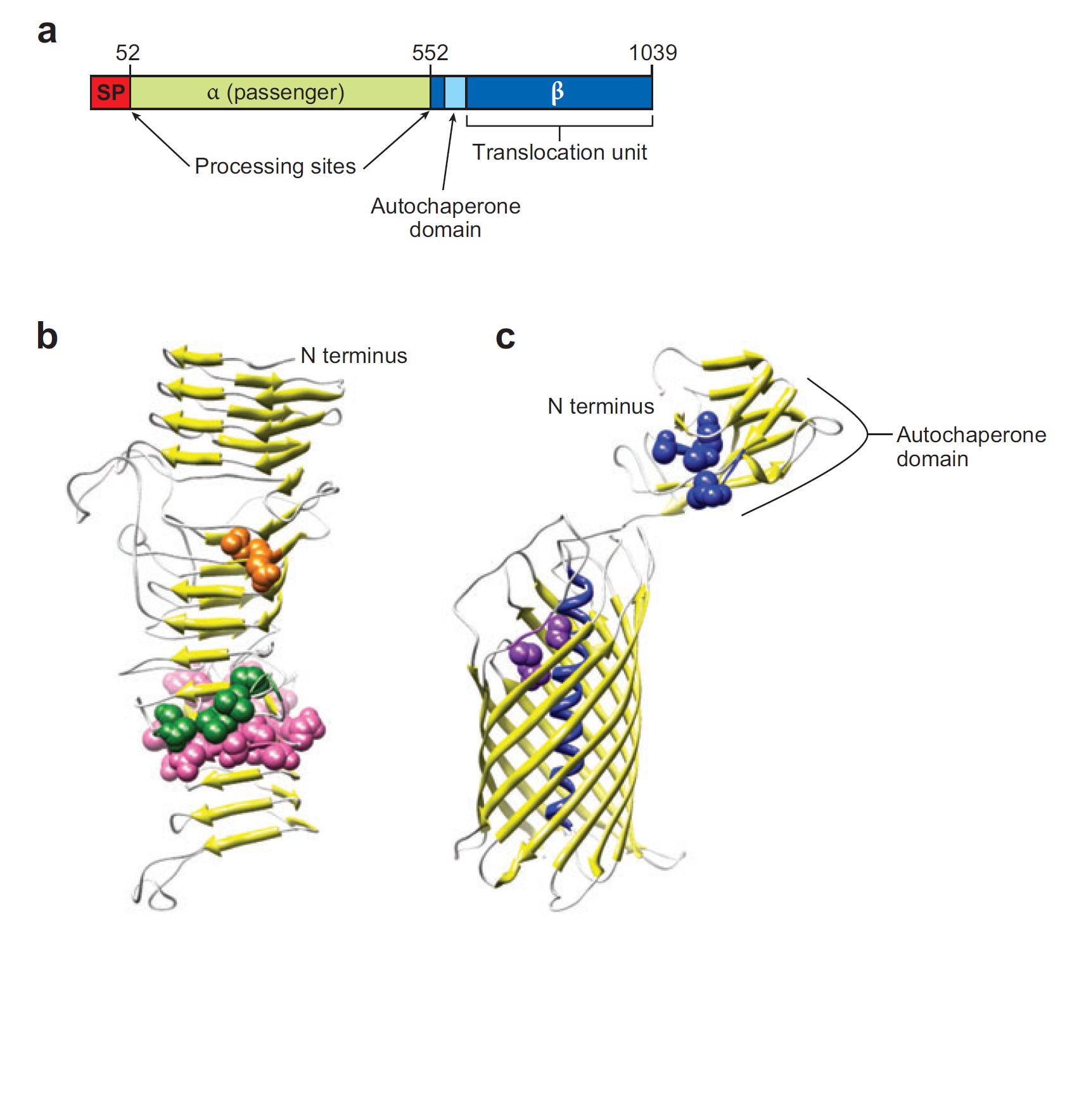

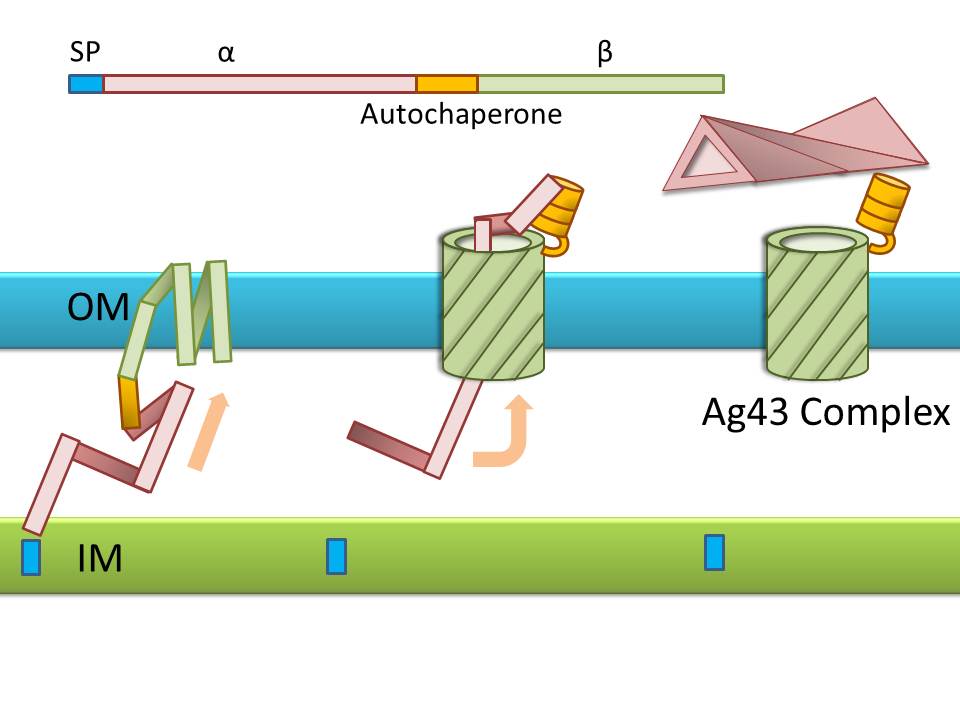

Ag43 is one of a kind of outer membrane proteins and belongs to auto-transporter family. This protein was derived from E. coli locus: flu, mapping on the E. coli K-12 chromosome. Other E. coli strains also have same gene, but this K-12 strain’s Ag43 cause the most rapid aggregation compared with other strain’s Ag43 [2]. Typical auto-transporter domains: signal peptides, N-proximal passenger domain (α43 : processing sites), autochaperon domain and C-terminal β-barrel domain (β43 : translocation unit) are found in the protein. These domains promote cell-to-cell auto-aggregation through the intermediate function.

Signal peptide is present at the N-terminus of this protein and translated with α43 and β43. In the presence of this signal, polypeptides consisted of other domains can cross from inner membrane to outer membrane. β43 is mainly composed of β-barrel structure. Some of membrane protein, particularly auto-transporter family has this domain which inserts into the outer membrane to work as anchor for passenger domain, and as pathway that allows passenger domain to cross from periplasm to outer membrane. Another domain which exists in the β43, the auto-chaperon domain stabilizes in near the outer pore of β-barrel then the domain associates folding of secreted passenger domain. α43 has β-helical structure and some identified motifs, e.g., aspartyl protease site, a leucine zipper motif and RGD motif. But none of the motifs are conserved in all agn43 alleles.(Fig. 4) That means the motifs does not play a functional role but plays a role in the structural integrity [2].

The actual secretional function of Ag43 is not still known. But about AIDA-I, One of the auto-transporter protein belonging to same group as Ag43, it is said that the AIDA-I passenger domain is auto-catalytically cleaved from complex with β-barrel and autochaperon after secreted, then remain on the outside of cell membrane with non-covalently bound to translocator β-barrel structure. This process would correspond to Ag43 because Ag43 is belonging to same family and has sequence similarity with AIDA-I [3]. It is generally confirmed that the structural and sequential similarity is correlated with functional similarity in proteomics. And the fact that the passenger domain is cleaved in the 60C will be additional evidence of non-covalent binding between each cell’s Ag43 [4]. The presence of transported Ag43 α domain is predicted in about 10nm of cell surface, so the cells that will aggregate with each other needs to be very close. If there were some obstacles near cells, they cannot aggregate. In other words, if there were rich other large proteins or cell surface structure, e.g., type 1 fimbriae and flagella on the cell membrane, Ag43 would not promote aggregation (Fig. 5) [5].

Experiments

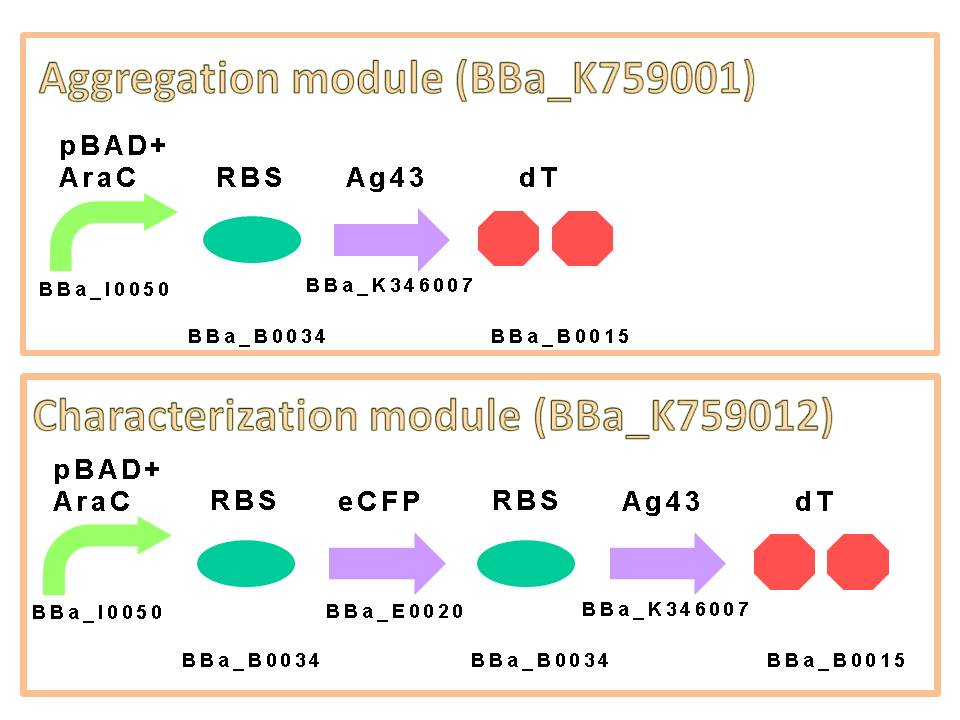

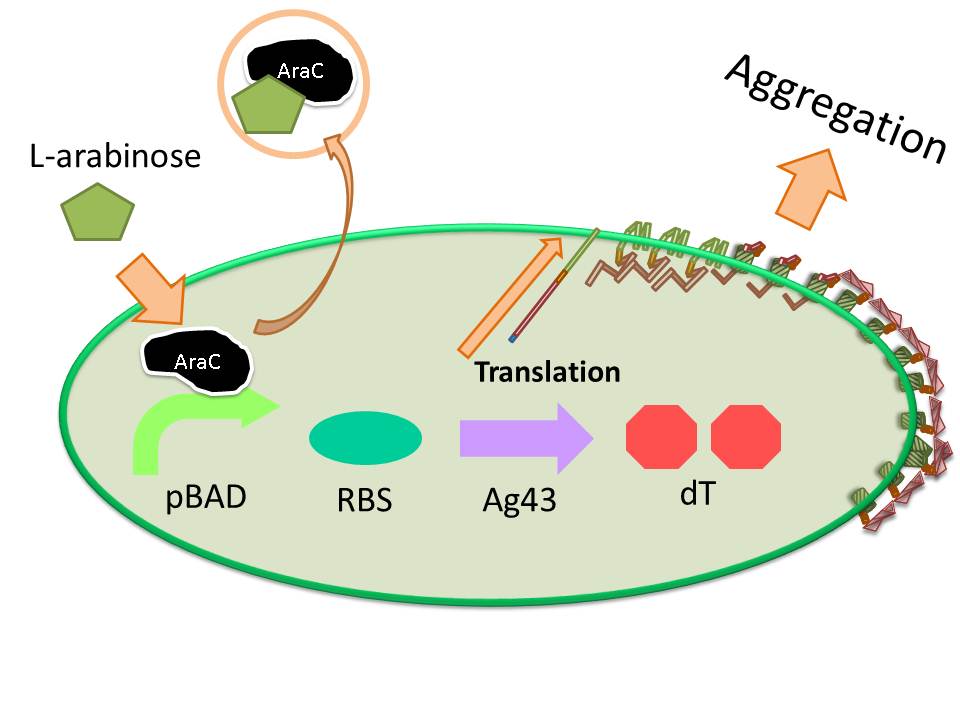

We appreciate to previous iGEM teams, especially iGEM 2010 Peking University team. We could easily get characterized Ag43 gene derived from K-12 strain flu gene. Compared with aggregation module of PKU iGEM 2010, our aggregation module is induced directly and executes aggregation more rapidly. We assembled a construct which is composed of pBAD+AraC (BBa_I0050) as promoter, ribosome binding site: RBS (BBa_B0034), Ag43 as protein coding region (BBa_K346007) and double terminator: dT (BBa_B0015) on a low copy plasmid pSTV28. (Fig. 6)

The induction of pBAD promoter is negatively controlled by AraC repressor. In the absence of L-arabinose, an AraC protein remains in pBAD promoter region and prevents transcription. In the presence of L-arabinose, AraC is released from pBAD by conformational change, and then RNA polymerase is allowed to start transcription of downstream sequence. Consequently, in this devise, we can induce Ag43 protein by addition of L-arabinose. And we inserted additional gene, eCFP: Cyan Fluorescent protein (BBa_E0020), upstream of Ag43 gene as indicator of expression of “Aggregation Module” (Fig. 7).

Furthermore, we executed codon optimization of Ag43 by JCat [7] and replaced 6 recognition sites of PstI which originally exists in wild-type Ag43 sequence with sequences suitable for BioBrick assembly. By this optimization, we would be able to improve the translational frequency of Ag43 and accelerate the time required for aggregation.

To aggregate cells each other, L-arabinose was added into LB liquid medium with appropriate antibiotics for induction of the function of “Aggregation Module”, and cultured in glass test tubes. The plastic tube was not suitable for producing large cluster of E. coli cells, since a strong affinity of E. coli expressing Ag 43 was observed onto the surface of inside of plastic test tube as shown in image 8.

Meanwhile, we tested the same observation using 300 ml Erlenmeyer flask containing 50 ml LB liquid medium and cultivated at 34C (See protocol page for experimental procedure).

We found that optimum temperature required for efficient aggregation by “Aggregation Module” is 34~37C. We didn’t observe aggregation at 30C even after 24 hr-culture. Reciprocal shaking of culture flask seemed to be better than rotation.

After culturing the aggregated E. coli, the clusters were harvested on nylon mesh by continuous strokes of injector (Fig. 9)(Image10).

We succeeded in filtering them by nylon mesh which has 250 um pore size then we have gained E. coli cake (Image11). And as our experimental fact, we filtered them by 200 um pore size mesh too. This result shows that we would be able to gain target product by this devise if we cultivated E. coli which has ability to produce target product.

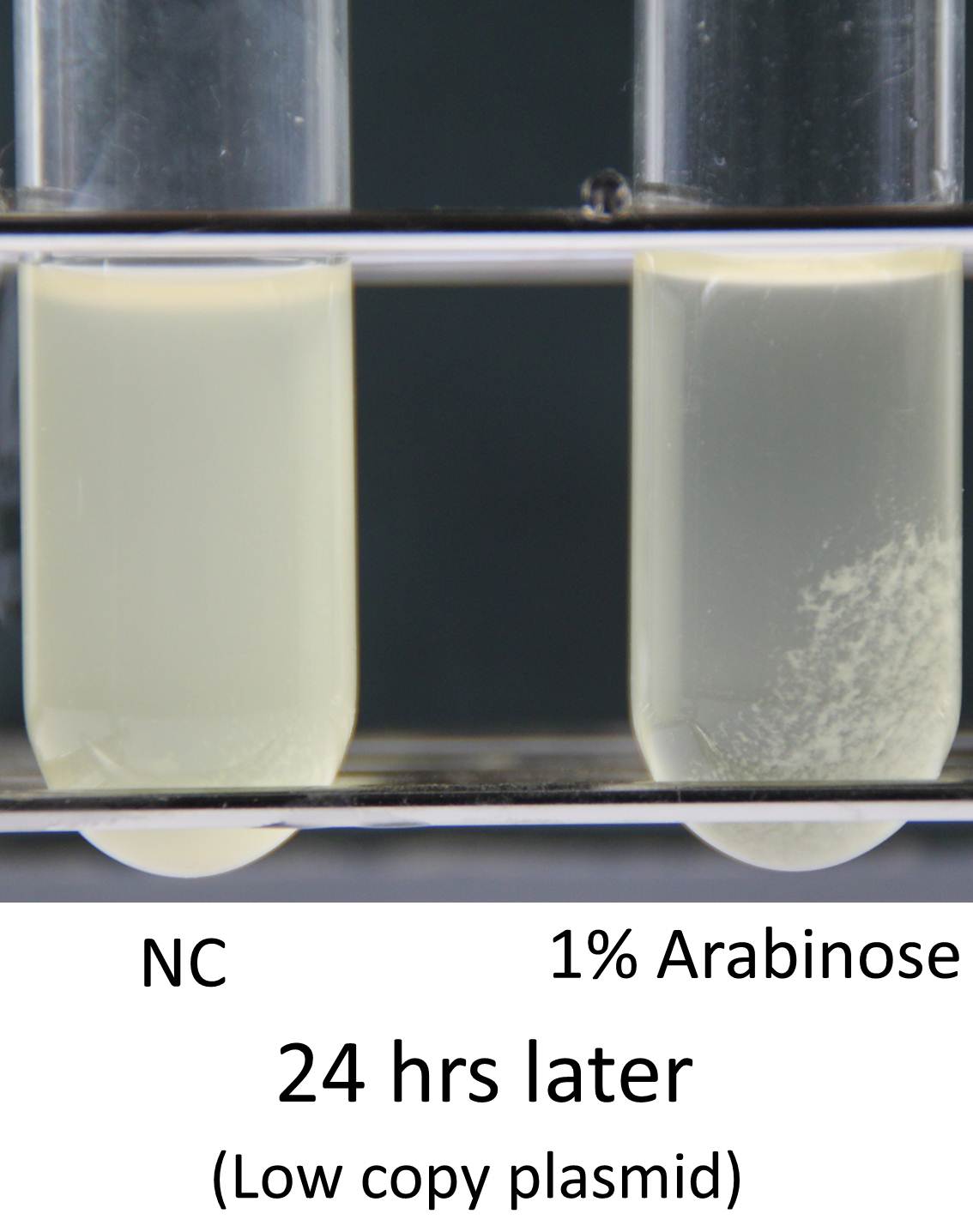

Induction of function of “Aggregation Module” was tested by observing appearance of aggregated E. coli cluster in the presence (right) or absence (left) of L-arabinose in culture medium (See Image12). Aggregated E. coli clusters were observed only in the culture medium containing L-arabinose. The results suggest that the auto-aggregation of E. coli is mediated by overexpressed Ag43.

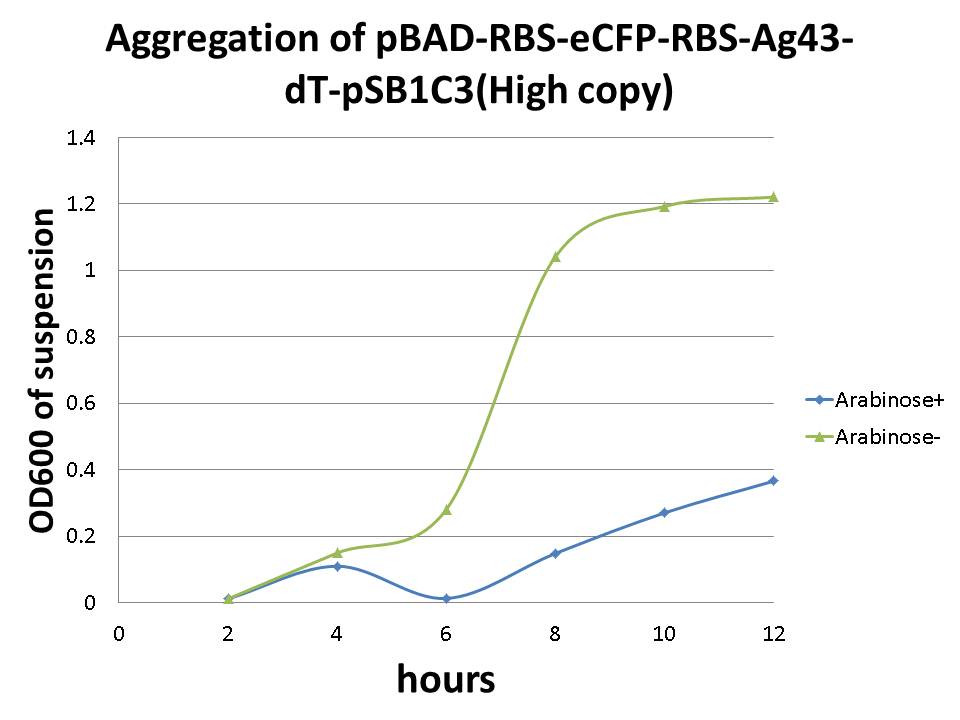

Besides above experiments, we tried to confirm a relationship between Ag43 expression and aggregation by monitoring signal associated with eCFP (indicator module) fused to “Aggregation Module”. During culture of the cells, we monitored change of OD600 as indicator of cell growth, and measured emission associated with eCFP as indicator of expression of “Aggregation Module” (See protocol page for experimental procedure). Plasmid structure is pBAD-RBS-eCFP-RBS-Ag43-dT-pSB1C3 and we cultivated at 37C for 12 hrs at 180 rpm.

The result showed there is relation between optical density and aggregation. At the same time cultivating cells, OD600 of each cell culture's suspension are increasing, but increasing ratio of arabinose added culture (Arabinose+) became lower than negative control (Arabinose-) (Image13). On the other hand, we couldn't observe the expression of eCFP.

References

[1] van der Woude, Marjan W Henderson, Ian R. Regulation and function of Ag43 (flu). Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2008. 62:153–69 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18785838

[2] P Caffrey and P Owen. Purification and N-terminal sequence of the alpha subunit of antigen 43, a unique protein complex associated with the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1989, 171(7):3634. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2661530

[3] Inga Benz, M. Alexander Schmidt. Structures and functions of autotransporter proteins in microbial pathogens. International Journal of Medical Microbiology 301 (2011) 461– 468. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21616712

[4]Glen C. Ulett, Jaione Valle, Christophe Beloin, Orla Sherlock, Jean-Marc Ghigo and Mark A. Schembri. Functional Analysis of Antigen 43 in Uropathogenic Escherichia coli Reveals a Role in Long-Term Persistence in the Urinary Tract Infect. Immun. 2007, 75(7):3233. DOI: 10.1128/IAI.01952-06. http://iai.asm.org/content/75/7/3233.abstract

[5] https://2010.igem.org/Team:Peking/Project/Bioabsorbent/InductiveAggregation

[6] http://openwetware.org/wiki/Arking:JCAOligoTutorial8

[7] http://www.jcat.de/

"

"