Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Results/cbc

From 2012.igem.org

Summary

Contents |

Introduction

In the field of cheap protein-extraction, cellulose binding domains (CBD) have made themselves a name. A lot of publications are available providing capture of a protein from the cell-lysate with a CBD-tag as a cheap purification strategy. Also enhanced segregation with CBD-tagged proteins have been observed. In this project the idea is different, the binding of our self-produced proteins to cellulose via a protein-domain-tag is taking advantage of the binding capacity of binding domains not only for purification reasons (it is still a great benefit), but also as an immobilization procedure for our laccases for later application.

To make a purification and immobilization-tag out of a protein domain, there are a lot of decisions and characterizations to do.

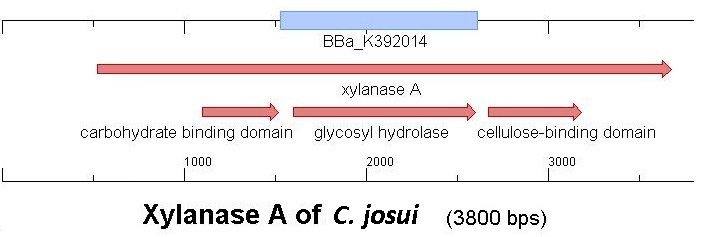

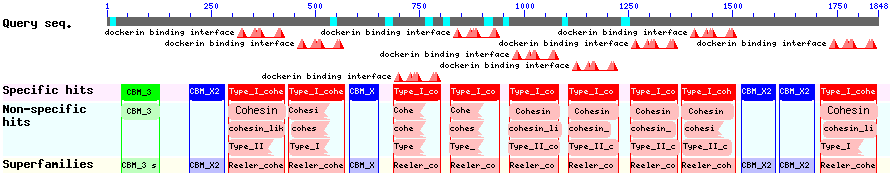

Starting with the choice of the binding domain, the first limitation is accessibility. The first place to look at is of course the [http://partsregistry.org Partsregistry]. A promising Cellulose binding motif of the C. josui xyn10A gene (<partinfo>BBa_K392014</partinfo>) was found and ordered for the project right from the spot. After some research concerning the sequence of that BioBrick, it turned out that the part is not the CBD of the Xylanase as it should be, but the glycosyl hydrolase domain of the protein (Figure 1). This result made the part useless for the project ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K392014:Experience complete review]) and it was the only binding domain in the [http://partsregistry.org Partsregistry] that fitted to the project.

Accessible organisms were searched via NCBI for binding-domains, -proteins and -motifs and work groups were asked if they could help out. The results of the database research were only two chitin/carbohydrate binding modules within the Bacillus halodurans genome (that strain was ordered for its laccase <partinfo>BBa_K863020</partinfo>). One is in the [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide/289656506?report=genbank&log$=nuclalign&blast_rank=1&RID=0JPT9WMS01N Cochin chitinase gene] and the other in a [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/BAB05022.1 chitin binding protein].

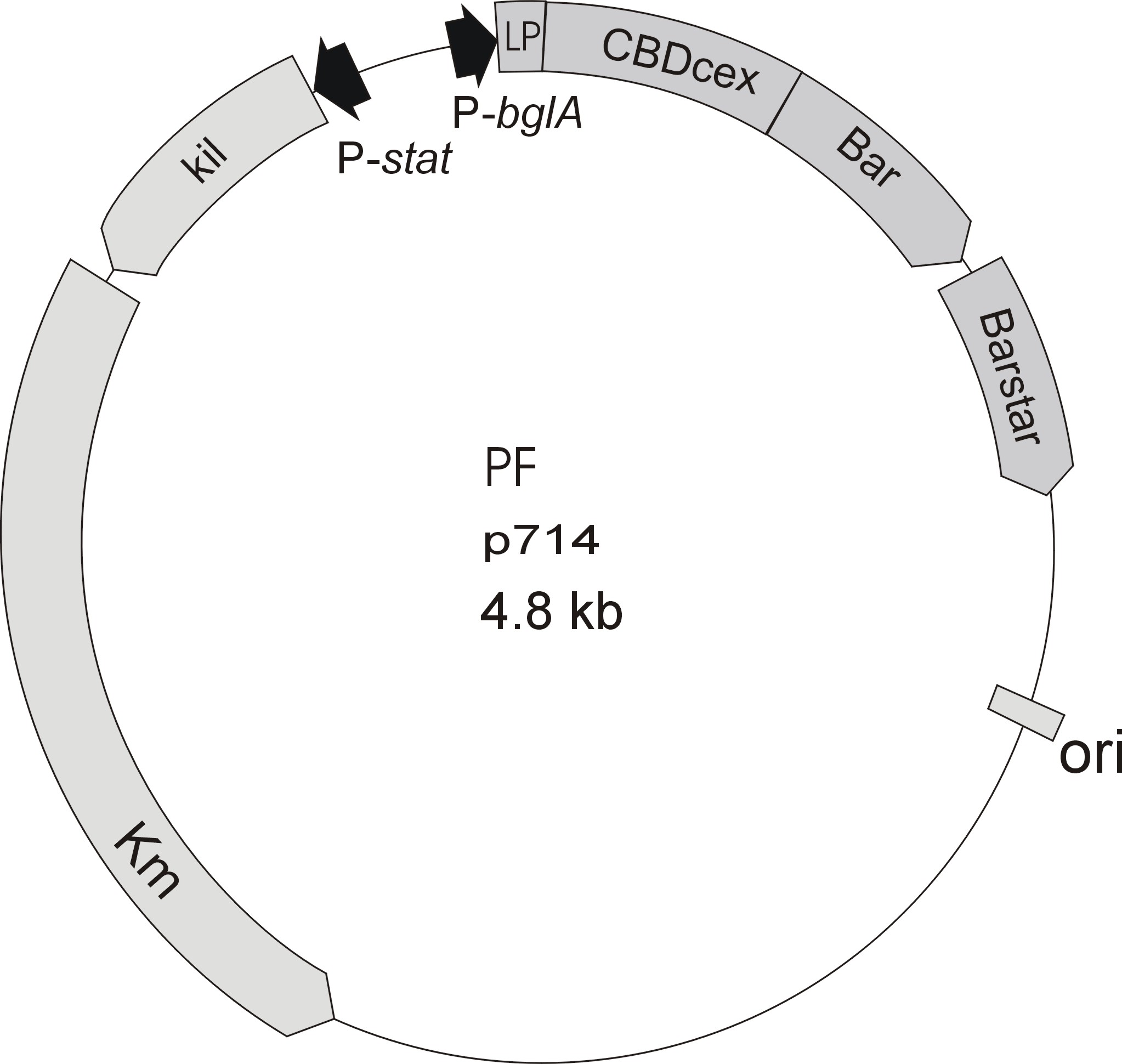

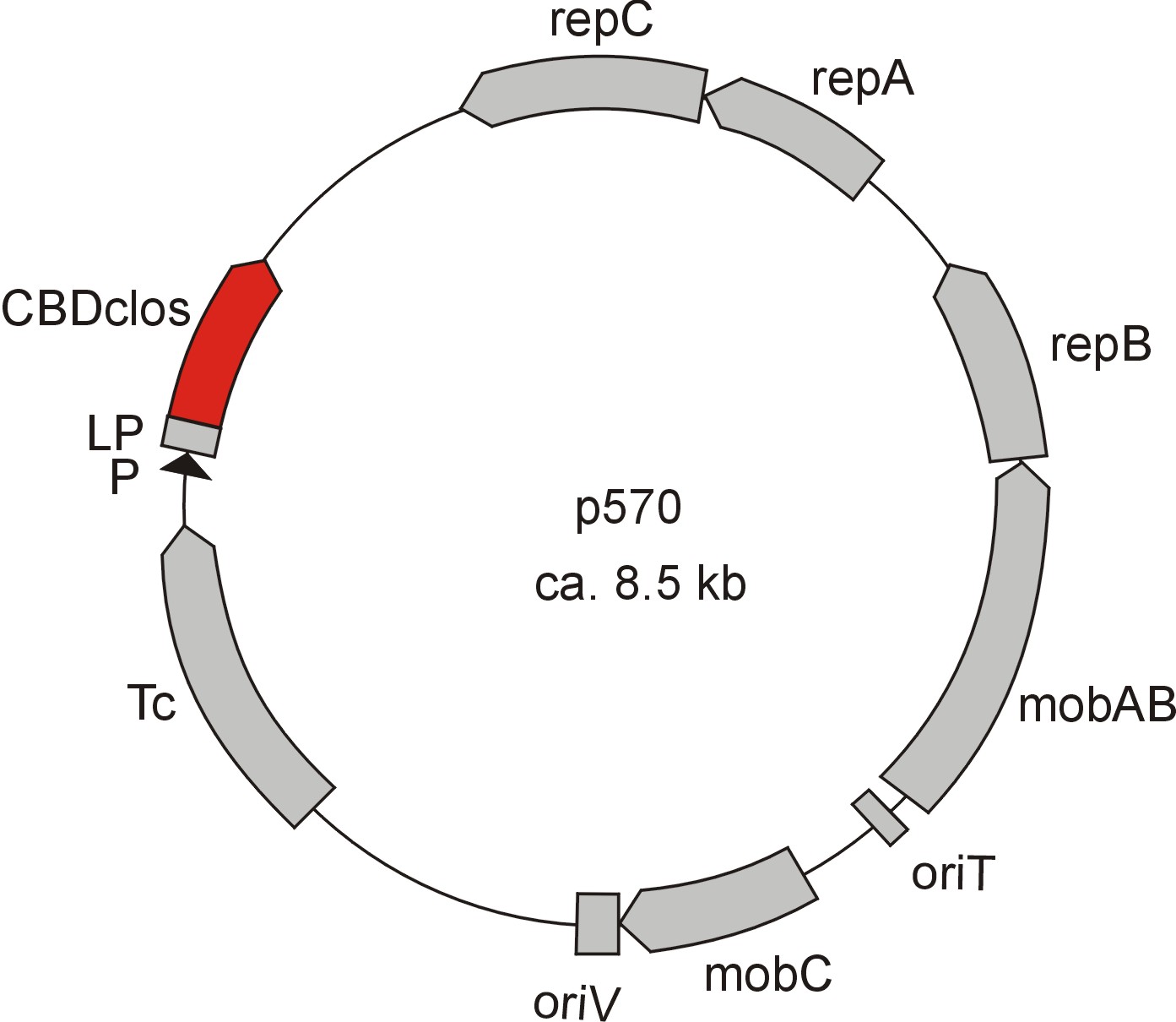

Meanwhile the Fermentation group of our university offered the use of two plasmids (p570 & p671), containing cellulose binding domains. The cellulose binding domain of the [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide/327179207?report=genbank&log$=nucltop&blast_rank=3&RID=152ZCN0E01N Cellulomonas fimi ATCC 484 exoglucanase gene] (CBDcex) and the cellulose binding domain of [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/M73817 Clostridium cellulovorans cellulose binding protein gene (cbpA)] (CBDclos). The decision was made to use these two domains. Staying within the cellulose binding domain-family and leave other protein domains like carbohydrate binding domains aside would keep the results comparable. For example, changing to a different binding material would change the binding capacities of both domains in the same way. Also both are bacterial CBDs and no post-translational modification and glycosylation had to be dealt with.

To get to know more about these two domains, their properties and their proteins, the NCBI databases were consulted. [http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ BLAST] was used to identify the cellulose binding domains and ExPASy-tools were used for further analyses.

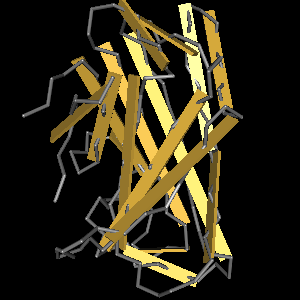

The CBD of the Cellulomonas fimi ATCC 484 exoglucanase gene (Figure 6) is a 100 amino acid long domain, close to the C-terminal ending of the protein with a theoretical pI of 8.07 and a molecular weight of 10.3 kDa. It is classified to be stable and belongs to the Cellulose Binding Modul family 2 (pfam00553/cl02709; Figure 5). Two tryptophane residues are involved in cellulose binding in this family which is only found in bacteria. Also, a CBM49 carbohydrate binding domain is found within the protein domain, where [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17322304?dopt=Abstract binding studies] have shown, that it binds to crystalline cellulose, which could be a possible target for immobilization.

The CBD of the [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/M73817 Clostridium cellulovorans cellulose binding protein gene (cbpA)] on the other hand is a N-terminal domain with 92 amino acids, theoretical pI of 4.56 and is also classified as stable. It belongs to the Cellulose Binding Module family 3 (pfam00942/cl03026; Figure 8) and is part of a very large cellulose binding protein with four other carbohydrate binding modules and a lot of docking interfaces for the proteins in its amino acid sequence (Figure 7).

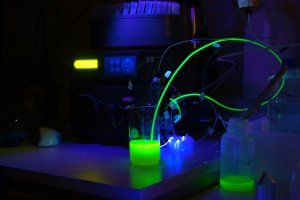

The Binding Assay

To measure the capacity and strength of the bonding between the cellulose binding domains and different types of cellulose many different assays have been made. One of the simplest and most often used is the fusion of the CBD to a reporter-protein, especially [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22305911a green or red fluorescent protein (GFP/RFP)] is very common. The place of the CBD is measured through the fluorescence of the fused GFP and quantification can easily been done.

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18573384 Protocol]:

- Harvest the E coli-cells producing the fusion-protein of CBD and GFP and centifuge 10 minutes at top speed.

- Re-suspend the cell-pellet in 50 mM Tris-HCl-Buffer (pH 8.0).

- Break down cells via sonication.

- Centrifuge at top speed for 20 minutes to get rid of the cell-debris.

- Take the supernatant and measure the emission at 511 nm (excitation at 501 nm) (<partinfo>E0040</partinfo>)

- Mix a definite volume of lysate with a definite volume or mass of e.g. crystalline cellulose (CC) or reactivated amorphous cellulose (RAC)

- Wait 15 (RAC) to 30 (CC) minutes

- Take supernatant and measure the emission at 511 nm again.

- The difference between the first an the second measurement is the relative quantity of what has bound to the cellulose.

Cloning of the Cellulose Binding Domains

The cloning of the CBDs should fit to the cloning of our laccases, so the BioBricks were designed with a T7-promoter and the B0034 RBS to have a similar method of cultivation. After investigating the restriction-sites it was found, that at least for the characterization of the CBDs a quick in-frame assembly of the CBDs and a GFP would be possible, because neither the CBDs nor the GFP (<partinfo>I13522</partinfo>) of the Partsregistry inherits a AgeI- or NgoMIV-site, which makes Freiburg-assembly possible. To do so, primers for the constructs <partinfo>BBa_K863101</partinfo> (CBDcex(T7)), carrying the CBDcex domain from the C. fimi exoglucanase and <partinfo>BBa_K863111</partinfo> (CBDclos(T7)), carrying the CBDclos domain from the C.cellulovorans binding protein were designed. The protein-BLAST of the two CBDs gave an exact picture of which bases belong to the binding domains and which do not. To be sure not to disturb the folding anyway 6 to 12 bases up and downstream of the domains as conserved sequences were kept. Even if the [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K863101 CBDcex]is an C-terminal domain both domains were made N-terminal, so the BioBricks can carry all regulatory parts and the linked protein can easily be exchanged. This would also be nice for other people using this part.

| CBDcex_T7RBS | 80 | TGAATTCGCGGCCGCTTCTAGAGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAAAGAGGAGAAATAATGGGT CCGGCCGGGTGCCAGGT |

| CBDcex_2AS-Link_compl | 56 | CTGCAGCGGCCGCTACTAGTATTAACCGGTGCTGCCGCCGACCGTGCAGGGCGTGC |

| CBDclos_T7RBS | 73 | CCGCTTCTAGAGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAAAGAGGAGAAATAATGTCAGTTGAATTTTACAACTCTAAC |

| CBDclos_2ASlink_compl | 63 | CTGCAGCGGCCGCTACTAGTATTAACCGGTGCTGCCTGCAAATCCAAATTCAACATATGTATC |

The listed complementary primers added, besides the Freiburg-suffix, a two amino acid glycine-serine-linker to the end of the CBDs. This is a very short linker, but as GFP-experts and [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17394253 publications] described GFP and CBDs are very stable proteins and should cope with a very short linker. The benefit of a short linker is that protease activity is kept minimal.

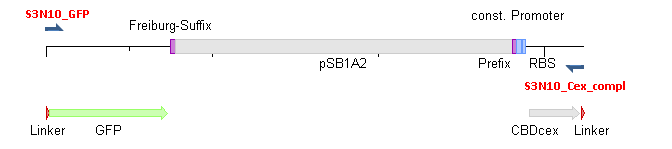

The GFP <partinfo>K863121</partinfo> used in the assay was an alternated version of the <partinfo>BBa_I13522</partinfo>. The primers that were made added a Freiburg-pre- and suffix to the GFP coding sequence and a His-tag to the C-terminus to get it purified for the measurements. This part <partinfo>BBa_K863121</partinfo> (GFP_His) should be easily added to the CBDs and assembled to the fusion-proteins <partinfo>BBa_K863103</partinfo> CBDcex(T7)+GFP_His and <partinfo>BBa_K863113</partinfo> CBDclos(T7)+GFP_His.

| GFP_Frei | 54 | TACGGAATTCGCGGCCGCTTCTAGATGGCCGGCATGCGTAAAGGAGAAGAACTT |

| GFP_His6_compl | 74 | CTGCAGCGGCCGCTACTAGTATTAACCGGTGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGTTTGTATAGTTCATCCATGCCATGTG |

Since a His-tag was added to the end of the GFP, an alternate version of the <partinfo>BBa_I13522</partinfo> had to be made to compare binding of GFP with and without CBD. Therefore, a forward primer was made, to amplify the whole <partinfo>BBa_I13522</partinfo> with the GFP_His_compl-primer to add the His-tag to the C-terminus.

| GFP_FW_SV | 39 | acgtcacctgcgtgtagctCGTAAAGGAGAAGAACTTTT |

Due to bad cleavage efficiency at the PstI restriction-site in nearly all PCR-products the cloning of the CBDs ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K863102 CBDcex(T7)] and [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K863112 CBDclos(T7)]) and especially the insertion of [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K863121 GFP_His] to the CBDs took a lot more time as expected. This was due to the fact that no additional bases were added to the 5' termini of the designed primers, thereby greatly reducing cleavage efficiency. When the problem was discovered and protocols adjusted or primers extended, cloning got a lot quicker and more successful.

As the project went on the T7-constructs did not seem to work. One suspected reason was that a stop codon (TAA) that was accidentally introduced between the RBS and ATG could be the reason. To solve the problem a change to a constitutive promoter (<partinfo>BBa_J61101</partinfo>) was made using the Freiburg-assembly. Therefore Freiburg forward primers for the CBDs were made.

| CBDcex_Freiburg-Prefix | 54 | GCTAGAATTCGCGGCCGCTTCTAGATGGCCGGCGGTCCGGCCGGGTGCCAGGTG |

| CBDclos_Freiburg-Prefix | 57 | GCTAGAATTCGCGGCCGCTTCTAGATGGCCGGCTCATCAATGTCAGTTGAATTTTAC |

The primers arrived just a few days before wiki freeze (Europe). Switching to the constitutive promoter had no obvious effect (no green colonies or culture), neither had changing the expression strain from E. coli KRX to E. coli BL21 for the T7-construct.

Since Regionals

After Amsterdam two approaches were made. One changing the order of the fused proteins and one altering the linker between CBD and the GFP. Both started simultaneously.One reason for the problems could be the too short space in between the two proteins, resulting in CBD and GFP hampering each other from folding correctly. To test and solve this, a very long linker with three serines followed by ten asparagines should be assembled in the already existing parts via a blunt end cloning.

| S3N10_Cex_compl | 40 | TTGTTGTTGTTCGAGCTCGAGCCGACCGTGCAGGGCGTGC |

| S3N10_Clos_compl | 40 | TTGTTGTTGTTCGAGCTCGAGCTGCCGCCGACCGTGCAGG |

| S3N10_GFP | 40 | CAATAACAATAACAACAACCGTAAAGGAGAAGAACTTTTC |

While the PCR worked properly, ligation of the linearized new plasmid was not successful and no transformed colonies could be found in two attempts. A reason for this could be insufficient phosphorylation of the PCR product. Because already Freiburg pre- and suffix primers for the CBDs were at hand the order of the fusion proteins could easily been changed, when a Freiburg suffix primer for the GFP would be available, so it was ordered.

| GFP_Freiburg_compl | 61 | ACGTCTGCAGCGGCCGCTACTAGTATTAACCGGTTTTGTATAGTTCATCCATGCCATGTGT |

When changing the fusing proteins to GFP N-terminal and CBD C-terminal an additional single GFP was cloned in a plasmid behind a J61101 RBS to see the expression of the J23100/J61101 promoter/RBS and to have a corresponding protein for the assay as a negative control. The result was the same as before, no green colonies. The colony PCRs and digestions showed the right bands, but no construct and even the single GFP was expressed correctly. Sequencing later showed that a deletion of one of the first few bases of the ORF caused a frame shift. At this point in time it seemed as if the promoter/RBS did not work properly. So in spite of continuing working as planed on the linker between GFP and the CBDs, the efforts now focused on the usage of promoter and RBS. In the last week of lab work it was tried to assemble GFP with a CBD behind the strong B0034 RBS, followed by cutting this piece out with XbaI and PstI and ligate this insert via a standard suffix insertion with the J23100 promoter. After some unsuccessful attempts AgeI ran empty and could not be ordered in time. A last quick-shot with a PCR product of an old (but correct) assembly (CBDcex-GFP) and a single GFP_Freiburg went well in adding it to the RBS but did not show green glowing colonies when fused to the promoter.

Literature

Kavoosi et al. (2007) Strategy for selecting and characterizing linker peptides for CBM9-tagged fusion proteins expressed in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Bioeng. Oct 15;98(3):599-610.

Urbanowicz et al. (2007) A tomato endo-beta-1,4-glucanase, SlCel9C1, represents a distinct subclass with a new family of carbohydrate binding modules (CBM49). J Biol Chem. Apr 20;282(16):12066-74. Epub 2007 Feb 23.

Sugimoto et al. (2012) Cellulose affinity purification of fusion proteins tagged with fungal family 1 cellulose-binding domain. Protein Expr Purif. Apr;82(2):290-6. Epub 2012 Jan 28.

Hong et al. (2008) Bioseparation of recombinant cellulose-binding module-proteins by affinity adsorption on an ultra-high-capacity cellulosic adsorbent. Anal Chim Acta. Jul 28;621(2):193-9. Epub 2008 May 27.

| 55px | | | | | | | | | | |

"

"