Team:HKUST-Hong Kong/Characterization

From 2012.igem.org

Characterization

Introduction

In our project, we have characterized two promoters and the cell death device using different methods. The results indicate that our parts are functional and we can quantitatively control their activities by changing the experimental conditions.

Low Efficiency Constitutive Promoter Ptms

Background Information (link to Regulation and Control Module)

Objective

Our objective in characterizing this promoter is to test whether Ptms works in E. coli DH10B strain and determine its relative promoter unit (RPU) compared to the standard constitutive promoter (a promoter whose activity is arbitrarily valued at 1.0 by partsregistry.org).

Intended Result

1. Ptms should work in E. coli. This is supported by previous research (Moran et al., 1982).

2. The activity of Ptms should be relatively low.

Method

Instead of using the absolute promoter activity as the final result, our characterization was based on obtaining the in vivo activity of this constitutive promoter. Adopting this method enables us to eliminate errors caused by different experimental conditions and give a more convincing result.

By linking the promoter with GFP (BBa_E0240), the promoter activity was represented by the GFP synthesis rate which can be easily measured. E. coli carrying the right construct was then cultured to log phase. At a time point around the mid-log phase, the GFP intensity and OD595 values were measured to obtain the Relative Promoter Units (RPU).

Characterization Procedure

- Constructing BBa_K733009-pSB3K3 (Ptms-BBa_E0240-pSB3K3); Transforming BBa_I20260-pSB3K3 (Standard Constitutive Promoter/Reference Promoter) from the 2012 Distribution Kit;

- Preparing supplemented M9 medium (see below);

- Culturing E. coli DH10B strain carrying BBa_K733009-pSB3K3 and E. coli carrying BBa_I20260-pSB3K3 in supplemented M9 medium and measuring the respective growth curves;

- Measuring the GFP intensity and OD595 values every 15 minutes after the above mentioned E. coli strains are cultured to mid-log phase;

- Calculating the Relative Promoter Units (RPU) using the obtained data;

- Compiling the results.

Data Processing

- After E. coli carrying the right construct was grown to mid-log phase, GFP intensity and OD595 were measured every 15 minutes (up to 60 mins);

- For GFP intensity, curve reflecting GFP expression change was plotted; for OD595, average values were taken;

- GFP synthesis rate was then obtained by calculating the slope of linear regression line of the above mentioned curve;

- Absolute promoter activity of Ptms and BBa_I20260 were calculated by dividing the corresponding GFP synthesis rate over the average OD595 value;

- Averaged absolute promoter activity was then obtained by averaging the respective sets of absolute promoter activity values;

- Finally, R.P.U was calculated by dividing the averaged Ptms absolute promoter activity over the averaged BBa_I20260 absolute promoter activity.

Result

* Above: GFP expression curve for one set of data

2. The RPU of Ptms obtained was 0.046497. This shows that Ptms has a very low promoter efficiency in E.coli DH10B strain.

Discussion

Compared to BBa_I20260, it seems that E. coli carrying Ptms-GFP has a rather low GFP expression. This may cause some difficulties in deciding whether Ptms functions in E. coli or not. However, referring to the curve (for GFP Intensity), the GFP expression for Ptms increased gradually with respect to time. This suggests that Ptms functions in E. coli DH10B strain, although with a low efficiency. A possible reason for its low efficiency could be that Ptms was originally from B. subtilis but was functioning in a heterologous system when placed in E. coli. Due to time constraints, we were unable to characterize the promoter in B. subtilis, and we still hope that we can address this in the future.

Reference

Moran, C., Lang, N., LeGrice, S., Lee, G., Stephens, M., Sonenshein, A., et al. (1982). Nucleotide sequences that signal the initiation of transcription and translation in Bacillus subtilis..Molecular and General Genetics MGG,186, 339-346.

Supplemented M9 Medium Composition

1. 5X M9 Salt Composition (1L)

(2) 15g KH2PO4

(3) 2.5g NaCl

(4) 5.0g NH4CL

(2) 2ml of 1M MgSO4

(3) 100μl of 1M CaCl2

(4) 5ml of 40% glycerol

(2) 0.2% casamino acids

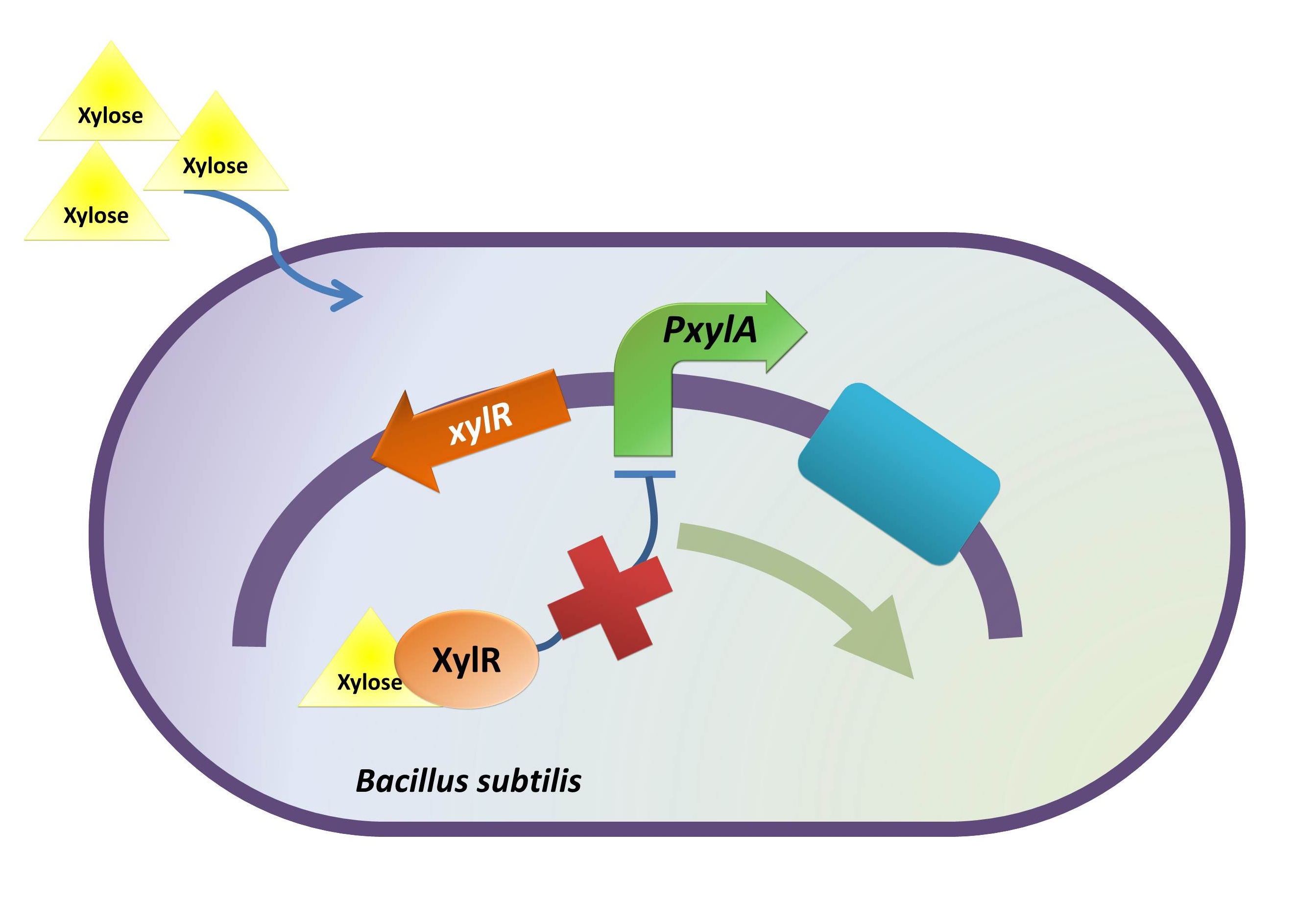

Xylose Inducible Promoter

Background Information (link to Regulation and Control Module)

Objective

On characterization, we want to test whether the promoter works in E. coli DH10B strain and if it works, what is the absolute promoter activity under varied experimental condition (i.e. xylose concentration).

Intended Result

1. Xylose inducible promoter is functional in E. coli.

2. After the inducer concentration has reached a certain level, a relatively stationary GFP expression level (expression upper-limit) should be observed.

Method

The absolute promoter activity was measured with respect to xylose concentration.

The same reporter gene (BBa_E0240) was used to indicate promoter activity. E. coli carrying the right construct was cultured to log phase. Following the addition of xylose at various predetermined concentrations, at a time point around the mid-log phase, the GFP intensity and OD595 were measured for every 30 mins (up to 120 mins). Independent curves indicating the GFP intensity units (of various xylose concentrations) with respect to time were then plotted, following which the respective absolute promoter activities were calculated.

Characterization Procedure

- Constructing xylR-PxylA-BBa_E0240-pSB1A2

- Preparing supplemented M9 medium (see below);

- Culturing E. coli carrying xylR-PxylA-BBa_E0240-pSB1A2 and E. coli without constructs in supplemented M9 medium and measuring the growth curve respectively;

- Culturing the above mentioned bacteria in supplemented M9 medium to log phase;

- Adding xylose at different concentrations to different sets of bacterial culture;

- Measuring the GFP intensity and OD595 values across time for every set of bacterial culture containing different xylose concentrations;

- Plotting independent curves showing the GFP intensity units of various xylose concentrations with respect to time;

- Plotting a graph to demonstrate the absolute promoter activity under different inducer concentrations;

- Compiling the results.

Data Processing

- After E. coli carrying the right construct was grown to mid-log phase, GFP intensity and OD595 were measured every 30 minutes (up to 120 mins);

- For GFP intensity, curve reflecting GFP expression change was plotted; for OD595, average value was taken;

- GFP synthesis rate was then obtained by calculating the slope of linear regression line of the above mentioned curve;

- Absolute promoter activity for the promoter under different inducer concentrations were calculated by dividing the corresponding GFP synthesis rate over the average OD595 value;

- Averaged absolute promoter activity was then obtained by averaging the respective sets of absolute promoter activity values.

Result

- Shown in the figure below, with the addition of xylose, GFP expression increased. This tells us that the xylose inducible promoter is functional in E. coli DH10B strain.

- When no xylose was added, a limited amount of GFP was expressed. This suggests that the xylose inducible promoter is to some extent leaky.

- [XX*XX]A relatively stationary GFP expression was observed after xylose concentration increased to 1% up to 5%. Despite some other variables (see discussion for more detail), we would say that the minimum inducer concentration for triggering full induction should lie in somewhere between 0 and 1%

- For 10% inducer concentration, the GFP expression was relatively lower. There could be several reasons for that, such as xylose metabolism by bacteria. (see discussion for more detail)

Discussion

- It is quite obvious that addition of xylose apparently induces the GFP expression. However, problem lies in that even when no xylose was added, a detectable amount of GFP was still expressed. This means that xylose inducible promoter was leaky. Reason for this could be that three mutagenesis had been done to the repressive gene of this promoter. Although we had adopted the most frequently used codon in B.subtilis for the mutagenesis, this may not work as our expectation in E.coli.

- For the observation of full induction. Our biggest problem is that the E.coli strain we used contains the xylose metabolic operon, which means xylose might be metabolized by the bacteria. To eliminate error caused by this factor, we chose to use relatively higher concentration for experiment. This further caused another problem on determining the minimum xylose concentration for full GFP induction as when xylose concentration increased to 1%, the observed GFP expression level already entered a relatively stationary phase. Therefore, based on this result, we would say that due to bacterial metabolism of xylose, we are not sure whether the real GFP maximum level is higher than our current observation. However, since for a xylose concentration above 1%, a relative stationary level of GFP was observed, we would say that the minimum xylose concentration to trigger the full induction lies below 1%. We hope that in the future we can confirm the exact concentration.

- For the decreased GFP expression at 10% xylose concentration, one possible reason is that the high osmotic pressure caused by the medium may inhibit the growth and metabolism of bacteria, thus reducing the GFP expression. Another possible reason could be that the over expression of induced GFP expression may disturb the normal bacteria function, leading to a low overall GFP expression.

Supplemented M9 Medium Composition

1. 5X M9 Salt Composition (1L)

(2) 15g KH2PO4

(3) 2.5g NaCl

(4) 5.0g NH4CL

(2) 2ml of 1M MgSO4

(3) 100μl of 1M CaCl2

(4) 5ml of 40% glycerol

(2) 0.2% casamino acids

ydcD-E Growth Inhibition Device

Background Information (link to Regulation and Control Module)

The rationale to include this growth inhibition device is that over-dose BMP-2 can cause unexpected proliferation of normal colon cells.(Zhang et al., 2012) Thus, a growth inhibition device is introduced and needs to be characterized.

Objective

The objective of this characterization is to find out what is the minimal concentration of xylose to inhibit the growth of our B. hercules.

Method

I. Construct

xylR: The transcriptional regulator for the xylose inducible promoter.

PxylA: The xylose inducible promoter.

ydcE (ndoA): The toxin gene encoding EndoA.

pTms: The low efficient constitutive promoter.

ydcD (endB): The antitoxin gene encoding YdcD.

II. Culture Medium

Supplemented M9 minimal medium (M9 salt, 1 mM thiamine hydrochloride, 0.2% casamino acids, 0.1 M MgSO4, 0.5 M CaCl2, 0.4% glycerol) was used for our characterization. The reason for this medium and 0.4% glycerol as the carbon source is that glucose can repress the induction of xylose. (Kim, Mogk & Schumann,. 1996) 25 mg/mL chloramphenicol was diluted 100 times and added to the medium to select the bacteria with our intended vectors. The final concentration gradient of xylose in the supplemented M9 minimal medium is: 0.05%, 0.10%, 0.15%, 0.20% and 0.25%.

III. Control and Experiment Group

Control Group: E. coli DH10β without any vector was engaged in characterization as control. It was inoulated into the supplemented M9 minimal medium with xylose concentration: 0.00%, 0.05%, 0.10%, 0.15%, 0.20%, 0.25%. Note that in the control group, the medium was not added with chloramphenicol.

Experiment Group: E. coli DH10β with our cell growth inhibition device were inoculated in the supplemented M9 minimal medium with xylose concentration: 0.00%, 0.05%, 0.10%, 0.15%, 0.20%, 0.25%. The total volume of the culture was 2mL for each test tube.

IV. Experiment

The bacteria cultures were incubated in 37 degree Celsius, shaked with 200 rpm for exactly 16 hours. After 16-hour incubation, the turbidity of the cultures were checked and photographed. Later, 50uL culture from one set of the experiments were taken and be spread on chloramphenicol 25 ug/mL LB plate for overnight incubation.

Result

Note that after spreading the culture on the plates, there were bacteria growing for all the tubes in the experiment groups. Admittedly, there were distinguishable difference between the concentration of 0.00%, 0.05% and 0.10% and the concentration of 0.15%, 0.20% and 0.25%: for the left three groups, the number of bacteria was much more than that in the right three ones. This result indicated that our E. coli did not die for the xylose induction, but its growth was inhibited.

Reference

Pellegrini O, Mathy N, Gogos A, Shapiro L, and Condon C. "The Bacillus subtilis ydcDE operon encodes an endoribonuclease of the MazF/PemK family and its inhibitor.." Molecular microbiology. 56.5 (2005): 1139-1148. Print.

Kim, L., Mogk, A., & Schumann, W. (1996). A xylose-inducible Bacillus subtilis integration vector and its application.. Gene, 181(1-2), 71-76.

Zhang J, Ge Y, Sun L, Cao J, Wu Q, Guo L, Wang Z. Effect of Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 on Proliferation and Apoptosis of Gastric Cancer Cells. Int J Med Sci 2012; 9(2):184-192.

Colon Tumor Binding System

Abstract(link to Target Binding Module)

A phage displaying peptide, RPMrel, was reported to have the ability to bind to poorly differentiate colon cancer cells while having significant lower binding ability to well-differentiate colon cancer cell and other normal tissue including lung, liver and stomach. (Kelly & Jones, 2003). Displaying RPMrel peptide on B. subtilis cell wall is expected to enable vegetative B. subtilis binding to colon cancer cell line specifically without adhering to other normal epithelial cell. In this characterization, B. subtilis was transfected with integration plasmid pDG1661- BBa_K733007 in order to displaying RPMrel on its cell wall. Empty vector pDG1661 is also transformed into B. subtilis as control. HT-29 (cancer adenocarcinoma) and HBE-16 (Human Bronchial epithelial cell) are engaged for adherence test to compare the binding affinity of experiment and control B. subtilis on cancer cell. The binding specificity of RPMrel displaying Bacillus subtilis was also investigated in this characterization.

Materials and Method

In order to characterize biobrick BBa_K733007 and demonstrate that it functions as expected in Bacillus subtilis, the recombinant DNA constructed needs to be inserted into integration plasmid pDG1661. Therefore, K733007 was first inserted into pBluescript ii KS+ through EcoRI and PstI site. Construct in pBluescript ii KS+ was further digested with EcoRI and BamHI site in order to insert into integration vector pDG1661. pDG1661-K733007 was transformed into E. coli DH10B and selected on Ampicillin plate (150 μg/ml). After replicated in E coli, pDG1661-K733007 was extracted and transformed into B. subtilis. LB plate containing 5μg/ml Chloramphenicol is used to select transformed B. subtilis. All E. coli and B. subtilis transformation were performed strictly follow the protocol uploaded in protocol section.

Colon adenocarcinoma (HT-29) was cultured in McCoy’s 5A medium supplement with 10% FBS in 5% CO2, 37℃ incubator. Normal human bronchial epithelial cell (HBE-16) was cultured in MEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS in 5%CO2, 37℃ incubator. 12-well plate was engaged to culture both cell into confluent.

Bacillus subtilis transformed with pDG1661-K733007 and the one transformed with pDG1661 empty vector were cultured separately in LB medium. Overnight cultures were diluted to OD650=0.1 and sub-culture for another 3 hours until OD650 reached 1. Bacteria were washed in 0.1M PBS 3 times and then re-suspended in McCoy' 5A (without FBS) and MEM medium (without FBS) respectively.

Confluent mammalian cells were washed with 0.1M PBS once before adding bacteria. 1ml B. subtilis suspensions were added into each well of mammalian cell culture plate. After co-culturing the mammalian cell with bacteria, 5 times washing with 0.1M PBS was performed then to wash away the free bacteria without attachment and move into further characterization.

Cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes in room temperature. After fixation, 0.0007 % crystal violet was used to stain cells overnight. Stains were washed away the next day with water and observed under inverted microscope with 400X magnificence.

0.1% Triton X-100 in 0.1M PBS was added into well after PBS washing and incubated for 10 minutes. Cells were then pellet and re-suspended in LB medium, plating on LB plate to determine CFU. (Sheng et al, 2011)

Result

Co-cultured Bacillus subtilis with RPMrel peptide on HT-29 and controlled Bacillus subtilis on HT-29 were stained and observed under inverted microscope with 400X magnificence. As shown in figure 1, Bacillus subtilis and nucleus of HT-29 cell were stained in purple and both types of B. subtilis can be detected on HT -29 cell.

Figure 1: Gram stain of B. subtilis on confluent HT-29 cell.

A: Gram stain of HT-29 co-cultured with B. subtilsi with RPMrel peptide.

B: Gram stain of HT-29 co-cultured with control bacteria, B. subtilis without RPMrel peptide.

Serial dilutions were performed before plating and plates with colony between 25~300 were counted to calculate the CFU/ml. As shown in table 1 and figure 1, more Bacillus subtilis with empty vector pDG1661 was detected on HT-29 cell line than the one of B. subtilis with RPMrel peptide on HT-29. Comparing the number of Bacillus subtilis with RPMrel retained on HT-29 and HBE16, more Bacillus subtilis can be detected on HBE16 cell. Two round of T-tests were further performed and it showed that no significant differences in the binding affinity between Bacillus subtilis with or without RPMrel to HT-29 cell (P>0.05) but the number of Bacillus subtilis with RPMrel peptide binding to HBE16 cells is significantly higher than the same bacteria bind to HT-29.

Discussion

Based on the result from table 1 and figure 2 and two t-test performed, it can be stated that B. subtilis with RPMrel displaying have no significant increase in binding ability to cancer cell line and the peptide displaying results in significant improvement in binding to normal epithelial tissue.

However, the statement above is just based on the evidence we have now. Because of time limitation, we haven’t demonstrated that LytC system can facilitate the displaying successfully be displaying on cell wall. Therefore, we can hardly tell the unexpected result is caused by the unexpected structure changes of RPMrel when displaying on cell wall or because of the failure of LytC system in transporting and localizing RPMrel on cell wall.

In addition, the gram staining method used in our characterization is not consistence during our one-month characterization work. Over staining happened from time to time and the cell layers were easily detached from the bottom of well after adding crystal violet.

Besides, more proper control group is needed for our experiment. Because of the limitation of source and time we have, no normal epithelial cell line from digestive system can be found and used in our work. Engaging HBE16 cells in experiment is a compromised but best choice we have so far. If possible, we will try to engage othrt cell lines in our experiment in order to draw solid conclusion in the future.

- Using BBa_K733008 (LytC system with flag tag on its C terminus) to verify the proper functioning of the cell wall binding system.

- Developing some more reliable staining method to demonstrate the adherence between B. subtilis and mammalian cell.

- Proper control bacteria and proper control cell line need to be added in our characterization in order to obtain reliable and solid conclusions.

Reference

Haiqing Sheng, Wang Jing, Lim Ji Youn, Davitt Christine, Minnich Scott A. & Hovde Carolyn J. 2012. Internalization of Escherichia coli O157:H7 by bovine rectal epithelial cells. Frontiers of Microbiology. (2012.2.32)

Kimberly A. Kelly & Jones David A.2003. Isolation of a Colon Tumor Specific Binding Peptide Using Phage Display Selection. Neoplasia. 5: 437 – 444

Project

Human Practice

"

"