Team:ETH Zurich/Modeling/Photoinduction

From 2012.igem.org

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{:Team:ETH_Zurich/Templates/TestHeader}} | {{:Team:ETH_Zurich/Templates/TestHeader}} | ||

| - | + | [[File:sonne.png|frameless|500px|center]] | |

== Photoinduction == | == Photoinduction == | ||

Revision as of 12:53, 26 October 2012

Contents |

Photoinduction

Introduction

Photoreceptors are light-sensitive proteins, which are able to perform specific actions (e.g. act as kinases) upon light induction. They typically make use of photopigments (like flavin and bilin), which are structurally changed (photoisomerization) or reduced (photoreduction) as reaction to excitation by photons. Some photoreceptors can be activated and deactivated by light; others follow an exponential decay to a ground state after excitation. The rate constants for this reactions can be computed from the number of induction events, i.e. the number of photons causing such an event.

For E.colipse we needed to know the activation of various receptors (Lov-Tap, BLUF-EAL, Ccas1, Cph8, UVR-8) to predict the behaviour of our system. For each of these receptors we tested several light conditions and computed the effects of visible and UV-light. In particular we analysed the amount of UV radiation detected by the receptors.

Methods

Quantification of light

For our project we needed to quantify the irradiance of different light sources, like sun light, room light, various bulbs, LEDs and a UV transilluminator. We discretized the irradiance spectra of these sources and converted the energy flux [J m-2 s-1 nm-1] to the photons flux Nλ [mol m-2 s-1 nm-1].

For sun light we used the reference irradiation ASTMG173, which is the irradiation averaged over all US states over one year at an inclined plane at 37° tilt towards the equator. For artificial light sources we assumed reasonable distances to our probe and perpendicular irradiation. Room light was defined as 30 % of natural sun light and considers UV absorption of window glass. The specifications, references and assumptions of the light sources used can be found on our parameter page.

Figure 1 shows a comparison of the spectra of sun light, room light and the standard General Electric 200 W bulb.

We were aware, that light can be polarized, directed and non-coherent, but these characteristics were not relevant for our approximation.

Photoconversion cross section

To compute the fraction of the photon flux which in fact triggers an event we used the photoconversion cross section. This is a measure of the probability of such an event and is derived from [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beer-Lambert_law Beer-Lambert law].

The photoconversion cross section [m2 mol-1] at wavelength λ, is defined as σλ = 2.303 ελ Φλ, where ε [m2 mol-1] is the molar extinction coefficient and Φ is the quantum yield, i.e. the fractions photons actually inducing a receptor activation after being absorbed.

Figure 2 shows the results of this computation for activation (-a) and deactivaton (-b) of all receptors.

Since for most of the receptors only absorption spectra and extinction coefficients at absorption peak wavelengths were available, we assumed the extinction coefficient at each wavelength would be proportional to absorption. Furthermore we assumed the quantum yield would be independent of wavelength. More details are available on our parameter page.

Reaction rate constants

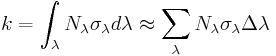

The first order reaction rate constants [s-1] for our ODE model can be computed as integral over all events at all wavelengths, i.e. the integral of the product of the photoconversion cross section σλ times the photon flux Nλ; In our case approximated numerically.

For CcaS and Cph1 we computed kon and koff, for Lov and YcgF kon only. Additionally our ODE model used dark decay rate constants for all of the receptors to approximate the spontaneous deactivation.

Validation of the model

The results of our method are consistent with the results of a corresponding book chapter [Mancinelli1986] and of the 2010 ETH Zuerich Team’s model. In both cases we reached high accordance; The small difference can be explained by our approximation of the extinction coefficient.

Results & Discussion

Our primary target was to compute rate constants as input for our ODE models. Nevertheless we gained immediate insights from these first results.

Reaction rate constants

The following table contains the reaction rate constants for source-receptor-combinations. The values for activation and deactivation are of the same order of magnitude except for all combinations of sun/room with Lov/YcgF. This is due to a fixed dark decay rate and no light induced deactivation of these receptors.

| sun | room | bulb200W | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kon | koff | kon | koff | kon | koff | |

| YcgF | 4.4e-001 | 5.8e-003 | 1.4e-001 | 5.8e-003 | 1.9e-003 | 5.8e-003 |

| Lov | 2.1e-001 | 5.8e-003 | 6.9e-002 | 5.8e-003 | 6.1e-004 | 5.8e-003 |

| CcaS | 6.6e-001 | 6.2e-001 | 2.2e-001 | 2.0e-001 | 4.8e-003 | 8.9e-003 |

| Cph1 | 2.6e+000 | 2.8e+000 | 8.7e-001 | 9.2e-001 | 3.7e-002 | 4.6e-002 |

Receptor activation

We took a frist glimpse on the expected receptor activation by approximating the steady state solution for the ODE system.

From these results we gained two insights. First, we had to assume YcgF and Lov (for both of them light only activates) would be fully activated at low irradiation. "Low" refers to the fraction of original irradiance, e.g. actual sun light intensity or the irradiance caused by a certain light bulb. This was an indication that we cannot use this receptors in real world applications. (See the upper part of figure 3.)

Second, Cph1 and CcaS - the receptors which are activated and deactivated by light - didn't show different activation levels for different light settings, i.e. they cannot be used to distinguish for example between sun and room light.

Actual UV photon flux

Since E.colipse is an UV protection system it is essential to know which fraction of a receptor's activation is due to UV radiation. To glance at the emission and absorption spectra only can be misleading because emission spectra are normally given as energy flux [J m-2 s-1 nm-1]. However, photons of low wavelength contain higher energy (Ep = h*c/λ), which means the actual flux of low wavelength photons is lower than obvious at first view.

An example is depicted in figure 4: The yellow area is the energy flux according irradiance spectrum. In contrast, the blue area is the photon flux. One can see a "shift" to the higher wavelengths, because it needs more "red photons" to transport the same amount of energy as "UV photons". For the sun the fraction of UV photons is 40.49 % less than one would expect from the power spectrum.

Fraction of rate constant due to UV

To get an idea of the relevance of UV radiation compared to visible light, we calculated the fraction of the reaction rate constants, which is due to "UV photons", i.e. the integral over all wavelengths up to 400 nm of the product photoconversion cross section times photon flux.

The results show that the UV fractions for all light source-receptor combinations are always less or equal 15.6 % (which is the maximum achieved by Lov). For Cph1 and CcaS, which are activated and deactivated by light, the difference between UV activation and deactivation is very small (approx. 5 %).

We assumed these values would be in the order of magnitude of noise and therefore concluded it would not be possible to measure the amount of UV radiation with a combination of several combined (UV and visible light) receptors.

References

- Brown, B. a, Headland, L. R., & Jenkins, G. I. (2009). UV-B action spectrum for UVR8-mediated HY5 transcript accumulation in Arabidopsis. Photochemistry and photobiology, 85(5), 1147–55.

- Christie, J. M., Salomon, M., Nozue, K., Wada, M., & Briggs, W. R. (1999): LOV (light, oxygen, or voltage) domains of the blue-light photoreceptor phototropin (nph1): binding sites for the chromophore flavin mononucleotide. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 96(15), 8779–83.

- Christie, J. M., Arvai, A. S., Baxter, K. J., Heilmann, M., Pratt, A. J., O’Hara, A., Kelly, S. M., et al. (2012). Plant UVR8 photoreceptor senses UV-B by tryptophan-mediated disruption of cross-dimer salt bridges. Science (New York, N.Y.), 335(6075), 1492–6.

- Cloix, C., & Jenkins, G. I. (2008). Interaction of the Arabidopsis UV-B-specific signaling component UVR8 with chromatin. Molecular plant, 1(1), 118–28.

- Cox, R. S., Surette, M. G., & Elowitz, M. B. (2007). Programming gene expression with combinatorial promoters. Molecular systems biology, 3(145), 145. doi:10.1038/msb4100187

- Drepper, T., Eggert, T., Circolone, F., Heck, A., Krauss, U., Guterl, J.-K., Wendorff, M., et al. (2007). Reporter proteins for in vivo fluorescence without oxygen. Nature biotechnology, 25(4), 443–5

- Drepper, T., Krauss, U., & Berstenhorst, S. M. zu. (2011). Lights on and action! Controlling microbial gene expression by light. Applied microbiology, 23–40.

- EuropeanCommission (2006). SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE ON CONSUMER PRODUCTS SCCP Opinion on Biological effects of ultraviolet radiation relevant to health with particular reference to sunbeds for cosmetic purposes.

- Elvidge, C. D., Keith, D. M., Tuttle, B. T., & Baugh, K. E. (2010). Spectral identification of lighting type and character. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 10(4), 3961–88.

- GarciaOjalvo, J., Elowitz, M. B., & Strogatz, S. H. (2004). Modeling a synthetic multicellular clock: repressilators coupled by quorum sensing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101(30), 10955–60.

- Gao Q, Garcia-Pichel F. (2011). Microbial ultraviolet sunscreens. Nat Rev Microbiol. 9(11):791-802.

- Goosen N, Moolenaar GF. (2008) Repair of UV damage in bacteria. DNA Repair (Amst).7(3):353-79.

- Heijde, M., & Ulm, R. (2012). UV-B photoreceptor-mediated signalling in plants. Trends in plant science, 17(4), 230–7.

- Hirose, Y., Narikawa, R., Katayama, M., & Ikeuchi, M. (2010). Cyanobacteriochrome CcaS regulates phycoerythrin accumulation in Nostoc punctiforme, a group II chromatic adapter. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(19), 8854–9.

- Hirose, Y., Shimada, T., Narikawa, R., Katayama, M., & Ikeuchi, M. (2008). Cyanobacteriochrome CcaS is the green light receptor that induces the expression of phycobilisome linker protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105(28), 9528–33.

- Kast, Asif-Ullah & Hilvert (1996) Tetrahedron Lett. 37, 2691 - 2694., Kast, Asif-Ullah, Jiang & Hilvert (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 5043 - 5048

- Kiefer, J., Ebel, N., Schlücker, E., & Leipertz, A. (2010). Characterization of Escherichia coli suspensions using UV/Vis/NIR absorption spectroscopy. Analytical Methods, 9660. doi:10.1039/b9ay00185a

- Kinkhabwala, A., & Guet, C. C. (2008). Uncovering cis regulatory codes using synthetic promoter shuffling. PloS one, 3(4), e2030.

- Krebs in Deutschland 2005/2006. Häufigkeiten und Trends. 7. Auflage, 2010, Robert Koch-Institut (Hrsg) und die Gesellschaft der epidemiologischen Krebsregister in Deutschland e. V. (Hrsg). Berlin.

- Lamparter, T., Michael, N., Mittmann, F., & Esteban, B. (2002). Phytochrome from Agrobacterium tumefaciens has unusual spectral properties and reveals an N-terminal chromophore attachment site. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 99(18), 11628–33.

- Levskaya, A. et al (2005). Engineering Escherichia coli to see light. Nature, 438(7067), 442.

- Mancinelli, A. (1986). Comparison of spectral properties of phytochromes from different preparations. Plant physiology, 82(4), 956–61.

- Nakasone, Y., Ono, T., Ishii, A., Masuda, S., & Terazima, M. (2007). Transient dimerization and conformational change of a BLUF protein: YcgF. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 129(22), 7028–35.

- Orth, P., & Schnappinger, D. (2000). Structural basis of gene regulation by the tetracycline inducible Tet repressor-operator system. Nature structural biology, 215–219.

- Parkin, D.M., et al., Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians, 2005. 55(2): p. 74-108.

- Rajagopal, S., Key, J. M., Purcell, E. B., Boerema, D. J., & Moffat, K. (2004). Purification and initial characterization of a putative blue light-regulated phosphodiesterase from Escherichia coli. Photochemistry and photobiology, 80(3), 542–7.

- Rizzini, L., Favory, J.-J., Cloix, C., Faggionato, D., O’Hara, A., Kaiserli, E., Baumeister, R., et al. (2011). Perception of UV-B by the Arabidopsis UVR8 protein. Science (New York, N.Y.), 332(6025), 103–6.

- Roux, B., & Walsh, C. T. (1992). p-aminobenzoate synthesis in Escherichia coli: kinetic and mechanistic characterization of the amidotransferase PabA. Biochemistry, 31(30), 6904–10.

- Strickland, D. (2008). Light-activated DNA binding in a designed allosteric protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105(31), 10709–10714.

- Sinha RP, Häder DP. UV-induced DNA damage and repair: a review. Photochem Photobiol Sci. (2002). 1(4):225-36

- Sambandan DR, Ratner D. (2011). Sunscreens: an overview and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Apr;64(4):748-58.

- Tabor, J. J., Levskaya, A., & Voigt, C. A. (2011). Multichromatic Control of Gene Expression in Escherichia coli. Journal of Molecular Biology, 405(2), 315–324.

- Thibodeaux, G., & Cowmeadow, R. (2009). A tetracycline repressor-based mammalian two-hybrid system to detect protein–protein interactions in vivo. Analytical biochemistry, 386(1), 129–131.

- Tschowri, N., & Busse, S. (2009). The BLUF-EAL protein YcgF acts as a direct anti-repressor in a blue-light response of Escherichia coli. Genes & development, 522–534.

- Tschowri, N., Lindenberg, S., & Hengge, R. (2012). Molecular function and potential evolution of the biofilm-modulating blue light-signalling pathway of Escherichia coli. Molecular microbiology.

- Tyagi, A. (2009). Photodynamics of a flavin based blue-light regulated phosphodiesterase protein and its photoreceptor BLUF domain.

- Vainio, H. & Bianchini, F. (2001). IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention: Volume 5: Sunscreens. Oxford University Press, USA

- Quinlivan, Eoin P & Roje, Sanja & Basset, Gilles & Shachar-Hill, Yair & Gregory, Jesse F & Hanson, Andrew D. (2003). The folate precursor p-aminobenzoate is reversibly converted to its glucose ester in the plant cytosol. The Journal of biological chemistry, 278.

- van Thor, J. J., Borucki, B., Crielaard, W., Otto, H., Lamparter, T., Hughes, J., Hellingwerf, K. J., et al. (2001). Light-induced proton release and proton uptake reactions in the cyanobacterial phytochrome Cph1. Biochemistry, 40(38), 11460–71.

- Wegkamp A, van Oorschot W, de Vos WM, Smid EJ. (2007 )Characterization of the role of para-aminobenzoic acid biosynthesis in folate production by Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. Apr;73(8):2673-81.

"

"