Team:ETH Zurich/Modeling/Construct2

From 2012.igem.org

Contents |

LovTAP/Cph8

In addition to the primary UVR8-TetRDBD system, we are constructing a second genetic circuit. This circuit consists of well-characterised photoreceptors and transcriptional repressors that have been previously shown to work in-vivo, providing a practical alternative to the UVR8-TetRDBD-based system. Although LovTAP mainly acts as a blue-light photoreceptor, a minority of induced reactions are still caused by UV light (~16%). In our model, strong irradiance with blue light as well as red light serves as an indicator for sun light. The other states of our decoder filter out common light sources.

Boolean logic

| Red-Lightinput | Blue-Lightinput | OutputGreen | OutputRed | OutputViolet/pabAB | Situation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | darkness |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | modern interior light source e.g. [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cold_cathode CCFL] |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | classical tungsten light bulb |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | resembles outdoor light |

Circuit

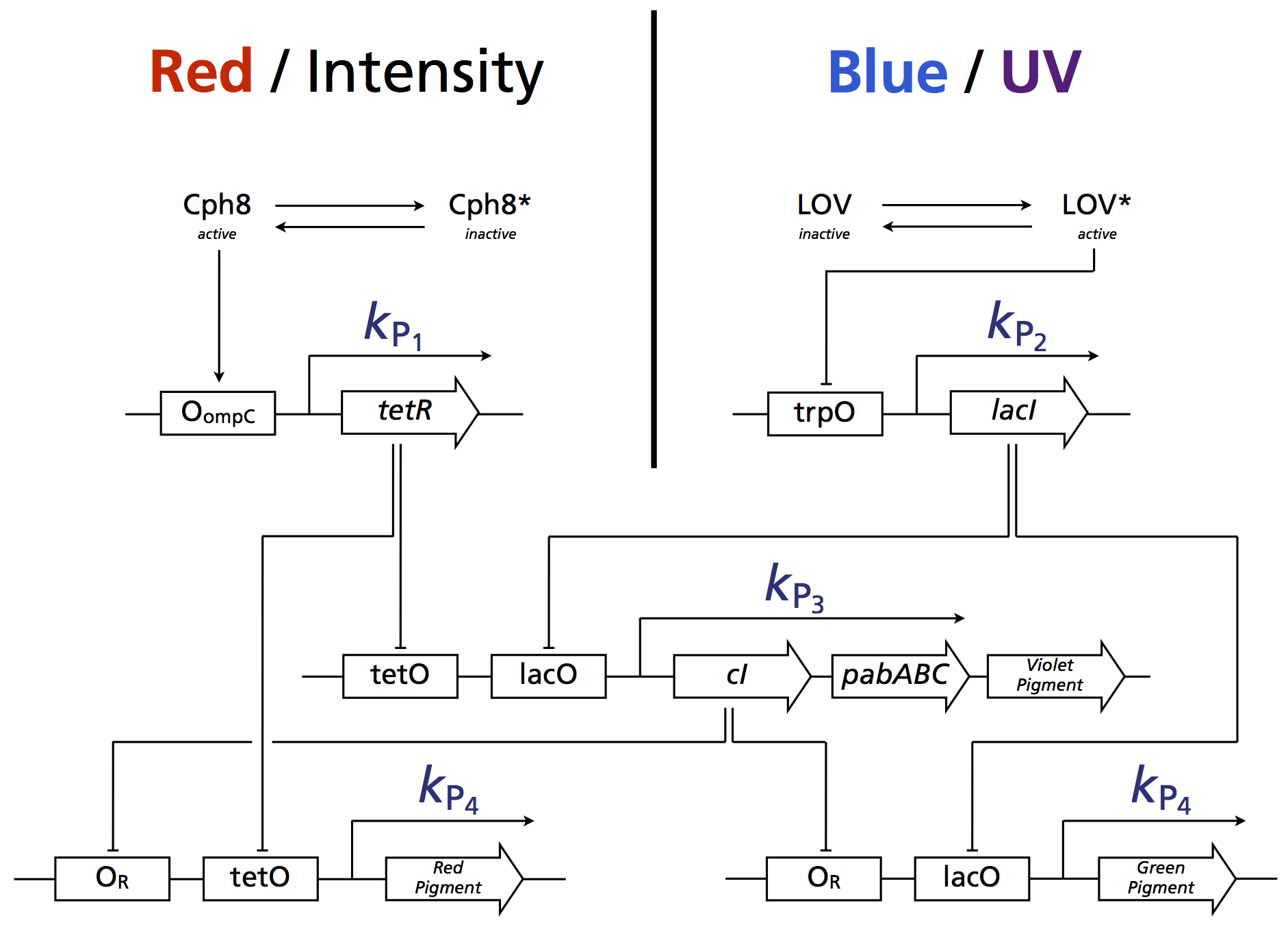

The following scheme illustrates the system:

Modelling assumptions

In order to analyse a number of properties of the system, the model needs to be tractable. For this, a number of assumptions and approximations have been made:

- Cph8 and LovTAP are conserved. This translates to a model not explicitly accounting for photoreceptor expression/degradation, as this will be the case for most systems in steady state anyway. Biological optimisation will instead focus on choosing the optimal ratio of promoter strength kP to degradation rate kdeg of the photoreceptors that effectively equal the steady state concentration of Cph8 and LovTAP.

- All photoconversion processes are modelled as 2-state processes.

- Degradation rates are identical for all proteins. While this obviously does not resemble biological reality, setting a degradation rate for every protein species individually is practically impossible, as such rate parameters are not ubiquitous in literature.

- The negative feedback has not been modelled explicitly here, as it has been accounted for in the previous simpler UVR8-TetRDBD model. As no oscillations are possible, the negative feedback loop merely reduces the dynamic range of the switching.

- Basal expression as fraction of complete induction is the same for all promoters (= 5% in our case).

ODEs

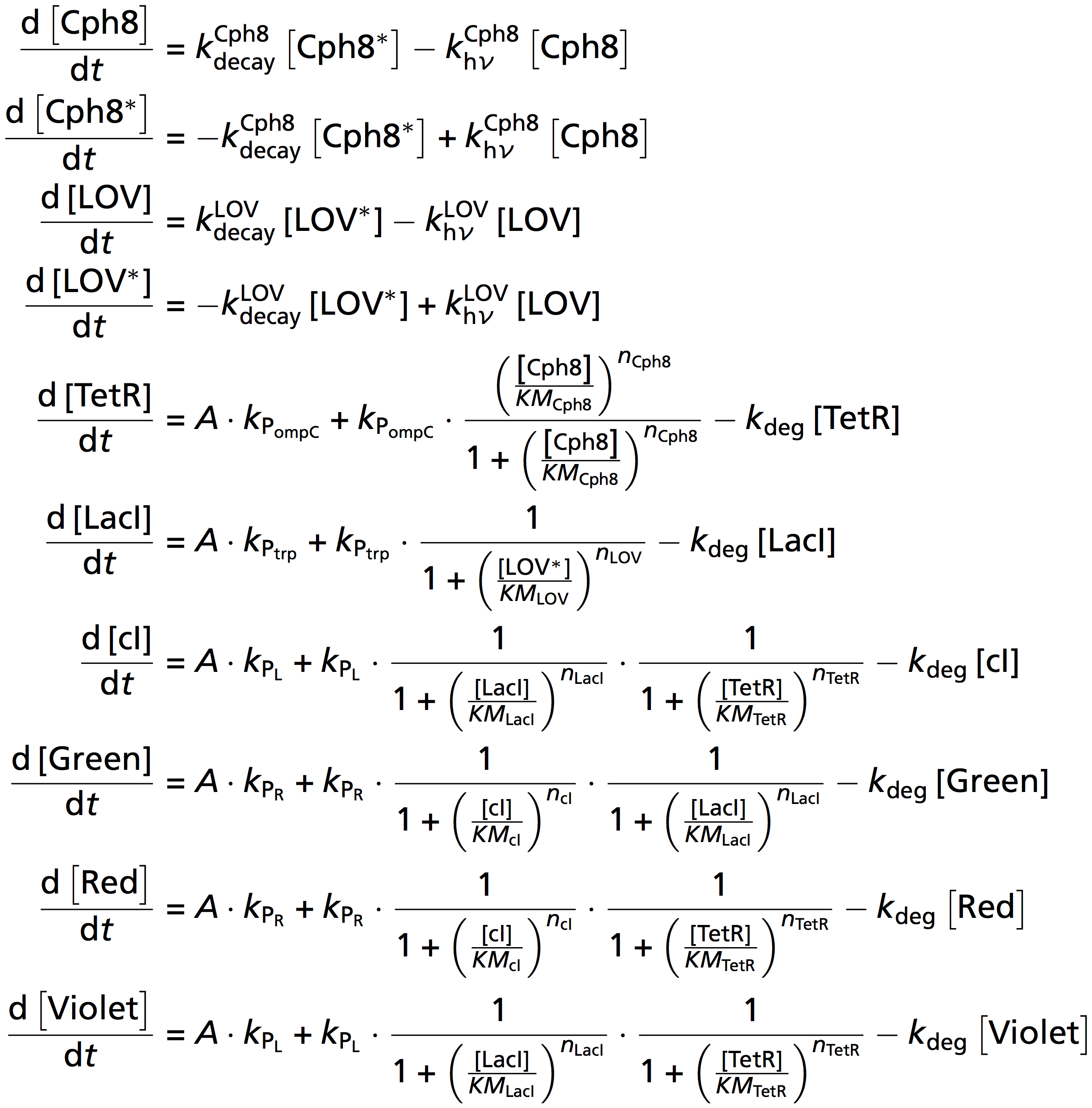

With the previous assumptions, the coupled system boils down to:

Find the parameters we used on our parameter page. For the optimisation of the promoter expression strengths, we have targeted steady-state repressor concentrations whose KM values equals the geometric mean of the steady-state concentrations between separating conditions, i.e. given a repressor concentration of conditions that are closest together, their steady-state values should yield a geometric mean equal to the repressor's respective KM values.

Results

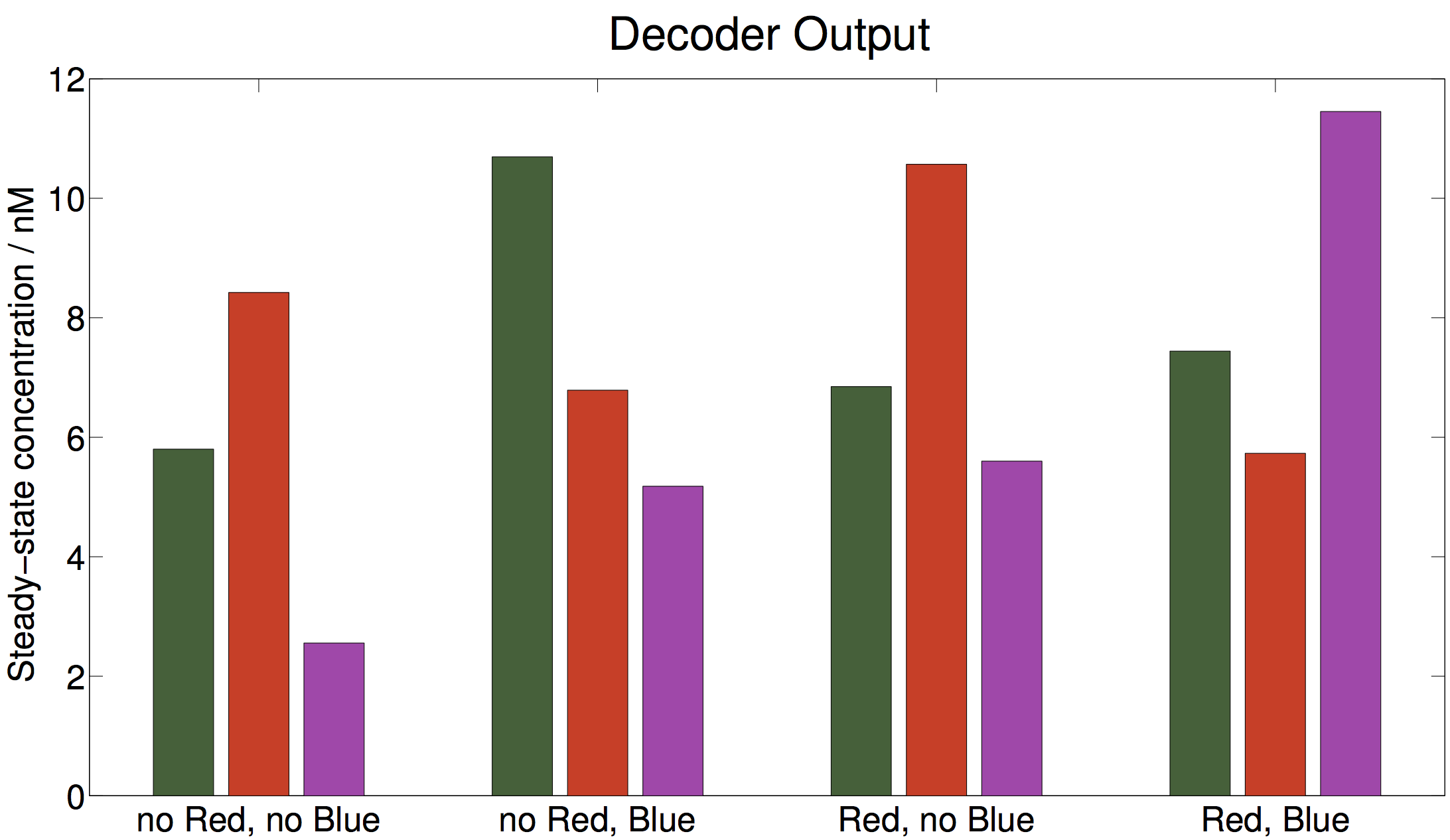

With 5% basal expression, a satisfactory separation can be achieved. Importantly, the expression of the violet pigment indicates a 2-fold induction when the system is induced both with blue and red light. Note that only these steady-state concentrations have a meaning - dynamics of the system might temporarily lift some pigment concentrations above the indicated values - they will eventually drop to the steady state. The separation between conditions is smaller than that of the UVR8-TetRDBD-system: this is due to the worse separation of Cph8, which only yields a 2.4 fold induction, compared to a near perfect separation for UVR8-TetRDBD.

Biological implications

The system has been tuned manually to maximise the dynamic range between conditions. This has resulted in promoter expression parameters that constrain the model:

This in effect requires the same promoter strengths to be employed in-vivo. Coming from a bioinformatics background, we propose a trial-and-error inspection for finding the correct promoter by using a binary-logarithmic "divide-and-conquer" method. This will reduce the number of different promoters required to be tested.

Considerations

In future, screening the literature for candidate sequences that exhibit less leakiness in practice should be considered.

Some uncertainty comes from the fact that no parameters are known for the Cph8 photoreceptor - such that its optimal concentration range can only be guessed.

References

- Brown, B. a, Headland, L. R., & Jenkins, G. I. (2009). UV-B action spectrum for UVR8-mediated HY5 transcript accumulation in Arabidopsis. Photochemistry and photobiology, 85(5), 1147–55.

- Christie, J. M., Salomon, M., Nozue, K., Wada, M., & Briggs, W. R. (1999): LOV (light, oxygen, or voltage) domains of the blue-light photoreceptor phototropin (nph1): binding sites for the chromophore flavin mononucleotide. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 96(15), 8779–83.

- Christie, J. M., Arvai, A. S., Baxter, K. J., Heilmann, M., Pratt, A. J., O’Hara, A., Kelly, S. M., et al. (2012). Plant UVR8 photoreceptor senses UV-B by tryptophan-mediated disruption of cross-dimer salt bridges. Science (New York, N.Y.), 335(6075), 1492–6.

- Cloix, C., & Jenkins, G. I. (2008). Interaction of the Arabidopsis UV-B-specific signaling component UVR8 with chromatin. Molecular plant, 1(1), 118–28.

- Cox, R. S., Surette, M. G., & Elowitz, M. B. (2007). Programming gene expression with combinatorial promoters. Molecular systems biology, 3(145), 145. doi:10.1038/msb4100187

- Drepper, T., Eggert, T., Circolone, F., Heck, A., Krauss, U., Guterl, J.-K., Wendorff, M., et al. (2007). Reporter proteins for in vivo fluorescence without oxygen. Nature biotechnology, 25(4), 443–5

- Drepper, T., Krauss, U., & Berstenhorst, S. M. zu. (2011). Lights on and action! Controlling microbial gene expression by light. Applied microbiology, 23–40.

- EuropeanCommission (2006). SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE ON CONSUMER PRODUCTS SCCP Opinion on Biological effects of ultraviolet radiation relevant to health with particular reference to sunbeds for cosmetic purposes.

- Elvidge, C. D., Keith, D. M., Tuttle, B. T., & Baugh, K. E. (2010). Spectral identification of lighting type and character. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 10(4), 3961–88.

- GarciaOjalvo, J., Elowitz, M. B., & Strogatz, S. H. (2004). Modeling a synthetic multicellular clock: repressilators coupled by quorum sensing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101(30), 10955–60.

- Gao Q, Garcia-Pichel F. (2011). Microbial ultraviolet sunscreens. Nat Rev Microbiol. 9(11):791-802.

- Goosen N, Moolenaar GF. (2008) Repair of UV damage in bacteria. DNA Repair (Amst).7(3):353-79.

- Heijde, M., & Ulm, R. (2012). UV-B photoreceptor-mediated signalling in plants. Trends in plant science, 17(4), 230–7.

- Hirose, Y., Narikawa, R., Katayama, M., & Ikeuchi, M. (2010). Cyanobacteriochrome CcaS regulates phycoerythrin accumulation in Nostoc punctiforme, a group II chromatic adapter. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(19), 8854–9.

- Hirose, Y., Shimada, T., Narikawa, R., Katayama, M., & Ikeuchi, M. (2008). Cyanobacteriochrome CcaS is the green light receptor that induces the expression of phycobilisome linker protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105(28), 9528–33.

- Kast, Asif-Ullah & Hilvert (1996) Tetrahedron Lett. 37, 2691 - 2694., Kast, Asif-Ullah, Jiang & Hilvert (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 5043 - 5048

- Kiefer, J., Ebel, N., Schlücker, E., & Leipertz, A. (2010). Characterization of Escherichia coli suspensions using UV/Vis/NIR absorption spectroscopy. Analytical Methods, 9660. doi:10.1039/b9ay00185a

- Kinkhabwala, A., & Guet, C. C. (2008). Uncovering cis regulatory codes using synthetic promoter shuffling. PloS one, 3(4), e2030.

- Krebs in Deutschland 2005/2006. Häufigkeiten und Trends. 7. Auflage, 2010, Robert Koch-Institut (Hrsg) und die Gesellschaft der epidemiologischen Krebsregister in Deutschland e. V. (Hrsg). Berlin.

- Lamparter, T., Michael, N., Mittmann, F., & Esteban, B. (2002). Phytochrome from Agrobacterium tumefaciens has unusual spectral properties and reveals an N-terminal chromophore attachment site. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 99(18), 11628–33.

- Levskaya, A. et al (2005). Engineering Escherichia coli to see light. Nature, 438(7067), 442.

- Mancinelli, A. (1986). Comparison of spectral properties of phytochromes from different preparations. Plant physiology, 82(4), 956–61.

- Nakasone, Y., Ono, T., Ishii, A., Masuda, S., & Terazima, M. (2007). Transient dimerization and conformational change of a BLUF protein: YcgF. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 129(22), 7028–35.

- Orth, P., & Schnappinger, D. (2000). Structural basis of gene regulation by the tetracycline inducible Tet repressor-operator system. Nature structural biology, 215–219.

- Parkin, D.M., et al., Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians, 2005. 55(2): p. 74-108.

- Rajagopal, S., Key, J. M., Purcell, E. B., Boerema, D. J., & Moffat, K. (2004). Purification and initial characterization of a putative blue light-regulated phosphodiesterase from Escherichia coli. Photochemistry and photobiology, 80(3), 542–7.

- Rizzini, L., Favory, J.-J., Cloix, C., Faggionato, D., O’Hara, A., Kaiserli, E., Baumeister, R., et al. (2011). Perception of UV-B by the Arabidopsis UVR8 protein. Science (New York, N.Y.), 332(6025), 103–6.

- Roux, B., & Walsh, C. T. (1992). p-aminobenzoate synthesis in Escherichia coli: kinetic and mechanistic characterization of the amidotransferase PabA. Biochemistry, 31(30), 6904–10.

- Strickland, D. (2008). Light-activated DNA binding in a designed allosteric protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105(31), 10709–10714.

- Sinha RP, Häder DP. UV-induced DNA damage and repair: a review. Photochem Photobiol Sci. (2002). 1(4):225-36

- Sambandan DR, Ratner D. (2011). Sunscreens: an overview and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Apr;64(4):748-58.

- Tabor, J. J., Levskaya, A., & Voigt, C. A. (2011). Multichromatic Control of Gene Expression in Escherichia coli. Journal of Molecular Biology, 405(2), 315–324.

- Thibodeaux, G., & Cowmeadow, R. (2009). A tetracycline repressor-based mammalian two-hybrid system to detect protein–protein interactions in vivo. Analytical biochemistry, 386(1), 129–131.

- Tschowri, N., & Busse, S. (2009). The BLUF-EAL protein YcgF acts as a direct anti-repressor in a blue-light response of Escherichia coli. Genes & development, 522–534.

- Tschowri, N., Lindenberg, S., & Hengge, R. (2012). Molecular function and potential evolution of the biofilm-modulating blue light-signalling pathway of Escherichia coli. Molecular microbiology.

- Tyagi, A. (2009). Photodynamics of a flavin based blue-light regulated phosphodiesterase protein and its photoreceptor BLUF domain.

- Vainio, H. & Bianchini, F. (2001). IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention: Volume 5: Sunscreens. Oxford University Press, USA

- Quinlivan, Eoin P & Roje, Sanja & Basset, Gilles & Shachar-Hill, Yair & Gregory, Jesse F & Hanson, Andrew D. (2003). The folate precursor p-aminobenzoate is reversibly converted to its glucose ester in the plant cytosol. The Journal of biological chemistry, 278.

- van Thor, J. J., Borucki, B., Crielaard, W., Otto, H., Lamparter, T., Hughes, J., Hellingwerf, K. J., et al. (2001). Light-induced proton release and proton uptake reactions in the cyanobacterial phytochrome Cph1. Biochemistry, 40(38), 11460–71.

- Wegkamp A, van Oorschot W, de Vos WM, Smid EJ. (2007 )Characterization of the role of para-aminobenzoic acid biosynthesis in folate production by Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. Apr;73(8):2673-81.

"

"