Team:Buenos Aires/Project

From 2012.igem.org

(→Tunable Synthetic Ecology) |

(→Motivation) |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| - | This is the key question that drives our motivation. How much of what we want to do are we actually able to do with the tools we have now a days? And more important, how can we increase our possibilities so that much more of what we can imagine becomes plausible? | + | This is the key question that drives our motivation. How much of what we want to do are we actually able to do with the tools that we have now a days? And more important, how can we increase our possibilities so that much more of what we can imagine becomes plausible? |

As we get more ambitious with our objectives in the field of synthetic biology, the complexity of biological circuits increases. This translates into an increase in the number and variety of different components that our designs must carry in order to be capable of the useful and interesting behaviors we want to achieve. | As we get more ambitious with our objectives in the field of synthetic biology, the complexity of biological circuits increases. This translates into an increase in the number and variety of different components that our designs must carry in order to be capable of the useful and interesting behaviors we want to achieve. | ||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

# Firstly, the greater the number of elements the system has, the greater the chances that they interact with each other, or with the chassis, in unexpected ways. | # Firstly, the greater the number of elements the system has, the greater the chances that they interact with each other, or with the chassis, in unexpected ways. | ||

| - | |||

# Furthermore, each component imposes a “load” on the cell, and '''there is probably an upper bound to the number of components one can introduce into a cell while keeping it viable''' | # Furthermore, each component imposes a “load” on the cell, and '''there is probably an upper bound to the number of components one can introduce into a cell while keeping it viable''' | ||

| Line 44: | Line 43: | ||

# The first one is '''how to stably maintain a co-culture of different strains''' (or species), when they most likely will have different growth rate and therefore one is bound to overtake the culture. Even in the unlikely case in which several strains grow at exactly the same rate, in the long term one will dominate because of “genetic drift”. | # The first one is '''how to stably maintain a co-culture of different strains''' (or species), when they most likely will have different growth rate and therefore one is bound to overtake the culture. Even in the unlikely case in which several strains grow at exactly the same rate, in the long term one will dominate because of “genetic drift”. | ||

| - | |||

# The second obstacle to overcome is '''how to couple the different sub-systems'''. If each strain does a specific task, it will have to interact in some way with the other strains to achieve the global function. This sort of cell-to-cell communication can be achieved with mechanisms as quorum sensing, that are already of common use in the synthetic biology community. | # The second obstacle to overcome is '''how to couple the different sub-systems'''. If each strain does a specific task, it will have to interact in some way with the other strains to achieve the global function. This sort of cell-to-cell communication can be achieved with mechanisms as quorum sensing, that are already of common use in the synthetic biology community. | ||

Latest revision as of 22:46, 26 October 2012

Contents |

Tunable Synthetic Ecology

We aimed to create a stable community of microorganisms that could be used as a standard tool in lab and industry. Our system would allow the co-culture of several genetically engineered machines in defined and tunable proportions, just like different species coexist in an ecosystem in nature. Hence the engineered organism would be a standard part! This defines a new level of modularity allowing the increase of the complexity of the system by moving to the community level.

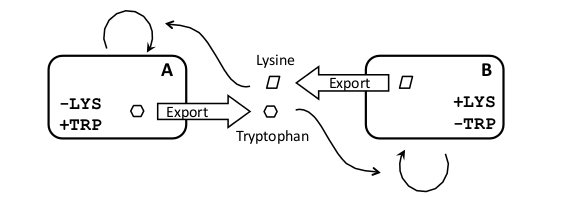

In order to do this we´ve come up with several plausible circuits designs and made in silico predictions of their behavior. We decided to build a “crossfeeding” system in which each strain produces and secretes an aminoacid the other strains need to grow. We therefore characterized two auxotrophic yeast strains (for tryptophan and histidine) and designed novel biobricks that regulate the export of Trp and His rich peptides, therefore regulating the growth rate of the complementary strain.

In the future this would allow for other modules to control the proportions of each strain, thus allowing dynamic and stimulus dependent changes in the abundances of each strain. It would also allow to build complex systems by combining different strains, each of which may have a specific function, that it is in you to decide.

Motivation

|

This is the key question that drives our motivation. How much of what we want to do are we actually able to do with the tools that we have now a days? And more important, how can we increase our possibilities so that much more of what we can imagine becomes plausible?

As we get more ambitious with our objectives in the field of synthetic biology, the complexity of biological circuits increases. This translates into an increase in the number and variety of different components that our designs must carry in order to be capable of the useful and interesting behaviors we want to achieve.

In our imagination, the increase in complexity may be only bounded to our creativity but experimentally there are several constrains and obstacles we can stump into in the way to our objective.

- Firstly, the greater the number of elements the system has, the greater the chances that they interact with each other, or with the chassis, in unexpected ways.

- Furthermore, each component imposes a “load” on the cell, and there is probably an upper bound to the number of components one can introduce into a cell while keeping it viable

These problems impose a limitation to the increase of the complexity in the synthetic system(Purnick and Weiss 2009).

One solution to this problem is to physically isolate sub-systems in different cells, creating a “division of labor”.

In this approach one would coculture different strains, each of which performs a specific task and interact with each other to achieve a desired system level behavior.

This approach would have several advantages:

- Sub-systems are isolated therefore reducing the number of unintended interactions

- This isolation allows for the same parts to be reutilized in different subsystems

- A new level of modularity is introduced; strains with specific functions can become “standard parts” to be combined in a higher level system.

- This approach should allow to easily scale-up the complexity of the system

However, there are two major obstacles to overcome for the proposed approach to work.

- The first one is how to stably maintain a co-culture of different strains (or species), when they most likely will have different growth rate and therefore one is bound to overtake the culture. Even in the unlikely case in which several strains grow at exactly the same rate, in the long term one will dominate because of “genetic drift”.

- The second obstacle to overcome is how to couple the different sub-systems. If each strain does a specific task, it will have to interact in some way with the other strains to achieve the global function. This sort of cell-to-cell communication can be achieved with mechanisms as quorum sensing, that are already of common use in the synthetic biology community.

In order to overcome these obstacles, we decided to construct a system in which two or more strain could be grown in stable, defined and tunable proportions.

Now you are free to imagine without restrain! We`ll make it happen.

We call this Tunable Synthetic Ecology.

Design

| After considering several possible schemes, we decided to construct a crossfeeding system, in which each strain produces and secretes a metabolite the other strain is incapable of producing and requires for growth (Figure 1). The main advantage of this scheme is that it maintains strain proportions in a way independent of signaling molecules, which will be required to couple sub-systems. |

Some examples of synthetic crossfeeding systems have been reported in the literature. For example two auxotrophic strains of E. coli (one for isoleucine and an other for leucine) were coevolved and selected for their ability to grow in a co-culture (Hosoda et al 2011). In another work two auxotrophic yeast strains were used, one for adenine and the other for lysine. In this case they were genetically modified to overproduce the relevant metabolite by elimination of the end-product feedback inhibition normally present in biosynthetic pathways (Shou et al. 2007). The co-culture could grow, but the metabolites were only released to the medium by cell lysis, therefore producing a lag phase in the growth of the culture and oscillatory dynamics.

Our design is based on aminoacid auxotrophy, allowing to engineer the secretion of the crossfeeding metabolite in the form of a peptide with a secretion tag. Furthermore, the production rate of this peptide can be easily regulated by controlling the strength of the promoter of its coding gene (see biobrick design section for details). The fact that the produced aminoacid is exported would effectively eliminate the end-product feedback inhibition, not by mutation, but by avoiding the accumulation of the aminoacid within the cell.

As a proof of principle we decided to construct a crossfeeding system with two Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast strains. We choose the tryptophan (Trp) and histidine (His) auxotrophs because they are common markers for yeast genetics and they are fairly rare aminoacid in proteins, therefore we reasoned that a small amount in the medium may have a big effect in the growth rate. An other advantage of using Trp is that its abundance can be easily measured in the medium by its fluorescence properties.

To gain some insight into the expected behavior of the system we build a mathematical model. With this model we tried to asses the feasibility of the design by estimating the parameters required for the system to work, and compare them with estimations for the parameters we could actually achieve. We had to do some initial characterization of the strains and estimation of relevant parameter.

Possible applications

The main purpose of the system is to allow a new modularity level, circuit isolation, parts reutilization and scale-up properties, as discussed above. Nevertheless, the “tunable synthetic ecology” could also be use in some specific application:

- Optimization of Bioreactor Output: If the steps of a complex reaction are carried out by different strains, the overall throughput of the process can be optimized by fine‐tuning the proportion of each strain. Our system would allow to easily modify these proportions.

- Synthetic Oenology: The ability to use several yeast strains in defined proportions in a fermentation process can allow new varieties of wines with unique properties to be created. This can be of interest to the local wine industry.

- Color Palette: By controlling the proportions of three strains, each of which produces a primary color pigment (or bioluminescence), one can control the color of the culture. If grown as a lawn on an agar plate one can then paint on a “cell canvas”. In the future this could be combined with light sensing parts to create a bacterial color photographic paper.

References

- Purnick, P.E. and R. Weiss, The second wave of synthetic biology: from modules to systems. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2009. 10(6): p. 410-22.

- Hosoda, K., et al., Cooperative adaptation to establishment of a synthetic bacterial mutualism. PLoS One, 2011. 6(2): p. e17105.

- Shou, W., S. Ram, and J.M. Vilar, Synthetic cooperation in engineered yeast populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2007. 104(6): p. 1877-82.

"

"