|

|

| (6 intermediate revisions not shown) |

| Line 50: |

Line 50: |

| | | | |

| | <p>The lux operon is a group of genes that are responsible for density-dependent bioluminescent behavior | | <p>The lux operon is a group of genes that are responsible for density-dependent bioluminescent behavior |

| - | in various prokariotic organisms such as <i>Vibrio fischeri</i> and <i>Photorabdus luminescens</i>. In <i>V. fischeri</i>, the operon is composed of 8 genes: LuxA and LuxB encode for the monomers of a heterodimeric luciferase; LuxC, LuxD and LuxE code for fatty acid reductases enzymes and LuxR and LuxI are responsible for the regulation of the whole operon.</p> | + | in various prokariotic organisms such as <i>Vibrio fischeri</i> and <i>Photorabdus luminescens</i> [[#12|12]]. In <i>V. fischeri</i>, the operon is composed of 8 genes: LuxA and LuxB encode for the monomers of a heterodimeric luciferase; LuxC, LuxD and LuxE code for fatty acid reductases enzymes and LuxR and LuxI are responsible for the regulation of the whole operon [[#13|13]].</p> |

| | <br /> | | <br /> |

| - |

| |

| | <p>Lastly LuxG is believed to act as a FMNH2 dependent FADH reductase, although luminescence is barely affected | | <p>Lastly LuxG is believed to act as a FMNH2 dependent FADH reductase, although luminescence is barely affected |

| - | in its absence. The n-decanal ( n= 9 to 14) substrate oxidization to n-decanoic acid by the LuxAB heterodimer is coupled with the reduction of FMNH to FMNH2 and the releasing of oxygen and x photons of light at x wavelength.</p> | + | in its absence [[#14|14]]. The n-decanal ( n= 9 to 14) substrate oxidization to n-decanoic acid by the LuxAB heterodimer is coupled with the reduction of FMNH to FMNH2 and the releasing of oxygen and light.</p> |

| | <br /> | | <br /> |

| - |

| |

| | <p>The carboxylic group of the product is then reduced to aldehyde by CDE proteins allowing the reaction to | | <p>The carboxylic group of the product is then reduced to aldehyde by CDE proteins allowing the reaction to |

| - | start over.</p> | + | start over [[#15|15]].</p> |

| | <br /> | | <br /> |

| - |

| |

| | <html> | | <html> |

| | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2012/5/56/Alagain_uc_chile.jpg" width="300" align="left" style ="margin-right:15px"></html> | | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2012/5/56/Alagain_uc_chile.jpg" width="300" align="left" style ="margin-right:15px"></html> |

| | <p>LuxAB genes have been widely used as reporters dependent on the addition of n-decanal to the culture | | <p>LuxAB genes have been widely used as reporters dependent on the addition of n-decanal to the culture |

| - | media and in 2010, the Cambridge iGEM team engineered LuxABCDEG to an <i>E. coli</i>-optimized biobrick | + | media [[#16|16]] and in 2010, the [https://2010.igem.org/Team:Cambridge Cambridge iGEM team] engineered LuxABCDEG to an <i>E. coli</i>-optimized biobrick |

| | format, uncoupling it from the LuxR and LuxI regulation.</p> | | format, uncoupling it from the LuxR and LuxI regulation.</p> |

| | <br /> | | <br /> |

| Line 71: |

Line 68: |

| | produced by this pathway is much more visually appealing than other systems from the registry (i.e XFPs), | | produced by this pathway is much more visually appealing than other systems from the registry (i.e XFPs), |

| | moreover, the light production doesn´t depend on a single peptide but on a whole pathway involving several genes, which makes it much more tunable, for instance, decoupling in time the substrate recovery from the luciferase reaction itself.</p> | | moreover, the light production doesn´t depend on a single peptide but on a whole pathway involving several genes, which makes it much more tunable, for instance, decoupling in time the substrate recovery from the luciferase reaction itself.</p> |

| - | | + | <br> |

| | + | <br> |

| | + | <br> |

| | <h1>Experimental Strategy</h1> | | <h1>Experimental Strategy</h1> |

| | <p>We have devised different strategies to achieve bioluminescence controlled under circadian rhythms. Here we describe the strategies used for building the constructs to reach our goals.</p> | | <p>We have devised different strategies to achieve bioluminescence controlled under circadian rhythms. Here we describe the strategies used for building the constructs to reach our goals.</p> |

| Line 94: |

Line 93: |

| | When confronted with the different available strategies to express the genes from the Lux operon in Synechocystis, we concluded that the one that best suits our need is by using integration plasmids. The reason for this is that the available plasmids that replicate in Synechocystis are very large (8 Kb) without even considering the genes we need to include in the constructs (that would sum up to a final 16 Kb aproximately). Such a large plasmid would prove very difficult to handle through molecular biology techniques, let alone transform Synechocystis. | | When confronted with the different available strategies to express the genes from the Lux operon in Synechocystis, we concluded that the one that best suits our need is by using integration plasmids. The reason for this is that the available plasmids that replicate in Synechocystis are very large (8 Kb) without even considering the genes we need to include in the constructs (that would sum up to a final 16 Kb aproximately). Such a large plasmid would prove very difficult to handle through molecular biology techniques, let alone transform Synechocystis. |

| | <br> | | <br> |

| - | Using integration plasmids also proposes an additional advantage, that is to produce successive integrations which allow accumulation of desirable elements in its genome. Integration in Synechocystis is undergone through double recombination of homologous DNA which also allows interruption of genes if wanted. In our case we have designed our system to produce suceptibility to copper as a biosafety measure to have further control over our recombinant Synechocystis. | + | Using integration plasmids also proposes an additional advantage, that is to produce successive integrations which allow accumulation of different desirable elements in the genome. Integration in Synechocystis is undergone through double recombination of homologous DNA which also allows interruption of genes if wanted. In our case we have designed our system to produce suceptibility to copper as a biosafety measure to have further control over our recombinant Synechocystis. |

| | | | |

| | <br> | | <br> |

| - | We have designed two constructs that have different recombination locations in the Synechocystis chromosome. We have named them according to what Utah iGEM team from 2010 proposed for [https://2010.igem.org/Construction_usu.html#Integration_Plasmid_Construction naming conventions]: | + | We designed two constructs that have different recombination locations in the Synechocystis chromosome. We named them according to what Utah iGEM team from 2010 proposed for [https://2010.igem.org/Construction_usu.html#Integration_Plasmid_Construction naming conventions]: |

| | | | |

| | <h3>pSB1C3_IntK</h3> [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K743006 BBa_K743006] | | <h3>pSB1C3_IntK</h3> [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K743006 BBa_K743006] |

| - | <p>This construct is an integrative plasmid which targets neutral recombination sites (slr0370 and sll0337). We selected this locus because it has been extensively used in the literature (REFERENCE) and it shown to have no deleterious effects on Synechocystis viability. We selected Kanamycin resistance as our transformation marker. [PUT LINK TO CONSTRUCT HERE].</p> | + | <p>This construct is an integrative plasmid which targets neutral recombination sites (slr0370 and sll0337). We selected this locus because it has been extensively used in the literature ([[#11| 11]]) and it shown to have no deleterious effects on Synechocystis viability. We selected Kanamycin resistance as our selectable marker. [PUT LINK TO CONSTRUCT HERE].</p> |

| | <br> | | <br> |

| | Using this backbone we have decided to put LuxAB under the transaldolase promoter.We have choose the transaldolase promoter to express the luciferase part of the operon, as in the literature the promoter is described as having a peak of expression at 2 hours past dusk, which we believe is just the right timing to "turn on the lamp". | | Using this backbone we have decided to put LuxAB under the transaldolase promoter.We have choose the transaldolase promoter to express the luciferase part of the operon, as in the literature the promoter is described as having a peak of expression at 2 hours past dusk, which we believe is just the right timing to "turn on the lamp". |

| | <br> | | <br> |

| | | | |

| - | We've found 2 versions of the bacterial luciferase which we intend to use on this construct. The first one is from Photorhabdus luminiscent K216008 from the 2009 Edinburgh iGEM team and the second one is part from the LuxBrick (K325909 from the 2010 Cambridge iGEM team) and originally comes from Vibrio fisherii but has been "E.coli optimized". | + | We've found 2 versions of the bacterial luciferase which we will use on this construct. The first one is of <i>Photorhabdus luminiscent</i> K216008 from the 2009 Edinburgh iGEM team and the second one is part from the LuxBrick (K325909 from the 2010 Cambridge iGEM team) and originally comes from <i>Vibrio fisherii</i> but has been "E.coli optimized". |

| | | | |

| | <h3>pSB1A3_IntC (Utah 2010 iGEM Team integration plasmid)</h3> | | <h3>pSB1A3_IntC (Utah 2010 iGEM Team integration plasmid)</h3> |

| Line 114: |

Line 113: |

| | <h3>pSB1C3_IntS</h3> | | <h3>pSB1C3_IntS</h3> |

| | <br /> | | <br /> |

| - | <p>Due to issues mentioned in the results page (PUT LINK HERE) we have decided to design another new plasmid backbone. | + | <p>Due to issues mentioned in the results page (PUT LINK HERE) we designed a new plasmid backbone. |

| - | This construct besides serving as a integration plasmid, makes Synechocystis susceptible to copper concentrations higher than X uM [[#10|10]]. We have designed this construct to interrupt the CopS gene as a biosafety measure to avoid the possibility of having a leakage of recombinant DNA to the environment. This plasmid has Spectynomycin resistance as the transformation marker. [PUT LINK TO CONSTRUCT HERE] | + | This is an integration plasmid which makes Synechocystis susceptible to copper concentrations higher than 0.75 uM [[#10|10]] by disrupting the CopS gene. We believe that this strategy serves as a biosafety measure to avoid the possibility of having a leakage of recombinant DNA to the environment. The plasmid uses Spectynomycin as a selectable marker. [PUT LINK TO CONSTRUCT HERE] |

| | </p> | | </p> |

| | We plan on expressing LuxCDEG under the control of the promoters Pcaa3 and PsigE (mentioned above). These promoters have peak activities 1 hour before dusk. We believe that we might enhance bioluminescence yield initially by setting the substrate production/regeneration part of the operon prior to the expression of the luciferase.(LINK TO MODELLING?) | | We plan on expressing LuxCDEG under the control of the promoters Pcaa3 and PsigE (mentioned above). These promoters have peak activities 1 hour before dusk. We believe that we might enhance bioluminescence yield initially by setting the substrate production/regeneration part of the operon prior to the expression of the luciferase.(LINK TO MODELLING?) |

| Line 121: |

Line 120: |

| | <h1>References</h1> | | <h1>References</h1> |

| | <div id="1"> | | <div id="1"> |

| - | (1) Hohmann-Marriott MF, Blankenship.(June 2011). Evolution of photosynthesis. Annual Review of Plant Biology Vol. 62: 515-548 | + | (1) Hohmann-Marriott MF, Blankenship.(2011). Evolution of photosynthesis. Annual Review of Plant Biology Vol. 62: 515-548 |

| | </div> | | </div> |

| | <br /> | | <br /> |

| | | | |

| | <div id="2"> | | <div id="2"> |

| - | (2) Jonathan P. Zehr. (April 2011) Nitrogen fixation by marine cyanobacteria. Trends in microbiology, Vol. 19, 162–17 | + | (2) Jonathan P. Zehr. (2011) Nitrogen fixation by marine cyanobacteria. Trends in microbiology, Vol. 19, 162–17 |

| | </div> | | </div> |

| | <br /> | | <br /> |

| Line 171: |

Line 170: |

| | </div><br /> | | </div><br /> |

| | <div id="10"> | | <div id="10"> |

| - | (10)Giner-Lamia, J., Lopez-Maury, L., Reyes, J. C., & Florencio, F. J. (August 2012). The CopRS two-component system is responsible for resistance to copper in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant physiology, 159, 1806-1818. | + | (10)Giner-Lamia, J., Lopez-Maury, L., Reyes, J. C., & Florencio, F. J. (2012). The CopRS two-component system is responsible for resistance to copper in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant physiology, 159, 1806-1818. |

| | </div> | | </div> |

| - | | + | <br> |

| | + | <div id="11"> |

| | + | (11)Kucho, K., Aoki, K., Itoh, S., & Ishiura, M., (2005). Improvement of the bioluminescence reporter system for real-time monitoring of circadian rhythms in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. Genes Genet. Syst. 80, p. 19–23 |

| | + | </div> |

| | + | <div id="12"> |

| | + | (12)Meighen, E. a. (1991). Molecular biology of bacterial bioluminescence. Microbiological reviews, 55(1), 123-42. |

| | + | </div> |

| | + | <div id="13"> |

| | + | (13)Dunlap, P. V. (1999). Quorum regulation of luminescence in Vibrio fischeri. Journal of molecular microbiology and biotechnology, 1(1), 5-12. |

| | + | </div> |

| | + | <div id="14"> |

| | + | (14)Luciferase, R. (2001). Differential Transfers of Reduced Flavin Cofactor and Product by Bacterial Flavin. Society, 1749-1754. |

| | + | </div> |

| | + | <div id="15"> |

| | + | (15) Kelly, C. J., Hsiung, C.-J., & Lajoie, C. a. (2003). Kinetic analysis of bacterial bioluminescence. Biotechnology and bioengineering, 81(3), 370-8. doi:10.1002/bit.10475 |

| | + | </div> |

| | + | <div id="16"> |

| | + | (16)Tehrani, G. A., Mirzaahmadi, S., Bandehpour, M., & Laloei, F. (2011). Molecular cloning and expression of the luciferase coding genes of Vibrio fischeri. Journal of Biotechnology, 10(20), 4018-4023. doi:10.5897/AJB10.2363 |

| | {{UC_Chilefooter}} | | {{UC_Chilefooter}} |

Main Goal

Natural cycles have always fascinated mankind, probably due to the mysterious mechanisms involved in them and the power they exert in our everyday life. Since the dawn of synthetic biology, engineering oscillatory systems has been a recurrent topic, being Ellowitz's represillator a classical example. Nevertheless, to date no iGEM team has accomplished the implementation of a robust oscillatory system. That will be our challenge for this year's iGEM project.

To reach our goal we designed a synthethic circuit that links to the endogenous circadian rhythm of Synechocystis PCC6803. As a proof of concept we are going to engineer the first light-rechargeable biological lamp: Synechocystis PCC 6803 cells that emit light only by night while recovering and producing the substrates in the day. We strongly believe this will serve as an enabling tool to any project requiring time control over a biological behaviour independently of the user's input.

Furthermore, the characterization of this chassis is a fundamental step to explore new systems with minimal inputs to replace E. coli, for example, in the biotechnological industry in order to achieve greener processes.

Rationale

Synechocystis PCC 6803

Cyanobacteria are prokaryotic photoautotrophs and they are believed to be the only group of organisms to

evolve oxygenic photosynthesis about 2.4 billion years ago 1. Although this biochemical breakthrough can’t

be understated, several cyanobacteria species also play a crucial role in the planet nitrogen cycle as marine

diazotrophs 2. Cyanobacteria are found almost in every environment in earth´s surface and interestingly, they

are one of the few prokaryotes known to have circadian rhythms accounting for their photosyntethic

lifestyle 3.

Synechocystis PCC6803 is a gram negative non-filamentous cyanobacteria and it was the third

prokaryote and the first photoautotroph whose genome was sequenced. Consequently, is has become a model organism as its genetic background has been widely studied.

Given the reasons mentioned above, it is of no surprise that Synechocystis PCC6803 (among other

cyanobacteria) has been extensively used for biotechnological applications and proposed as the “green E.coli”4.

With the dawn of Synthetic Biology, research has made use of Synechocystis for

commodity chemicals production and detection of water soluble pollutants among other applications5,6.

While aware of these practical applications, we (UC_Chile) are particulary interested in the well

characterized circadian behavior of this chassis 7 and its implications. There are several

genes known to oscillate in a daily basis, most of them related to respiration, photosynthesis and energy

metabolism 8, and it has been shown that reporter systems using these promoters show a

similar expression pattern 9.

Lastly, there are a lot of biobricks designed especially for Synechocystis or from its genome´s

sequence by previous iGEM teams (references) but sadly no one has ever characterized them in this chassis

and the registry lacks a set of tools for its transformation with standard biological parts. Moreover, to our

knowledge, no iGEM team has ever accomplished a successful direct Synechocystis transformation with naked DNA.

Lux Operon

The lux operon is a group of genes that are responsible for density-dependent bioluminescent behavior

in various prokariotic organisms such as Vibrio fischeri and Photorabdus luminescens 12. In V. fischeri, the operon is composed of 8 genes: LuxA and LuxB encode for the monomers of a heterodimeric luciferase; LuxC, LuxD and LuxE code for fatty acid reductases enzymes and LuxR and LuxI are responsible for the regulation of the whole operon 13.

Lastly LuxG is believed to act as a FMNH2 dependent FADH reductase, although luminescence is barely affected

in its absence 14. The n-decanal ( n= 9 to 14) substrate oxidization to n-decanoic acid by the LuxAB heterodimer is coupled with the reduction of FMNH to FMNH2 and the releasing of oxygen and light.

The carboxylic group of the product is then reduced to aldehyde by CDE proteins allowing the reaction to

start over 15.

LuxAB genes have been widely used as reporters dependent on the addition of n-decanal to the culture

media 16 and in 2010, the Cambridge iGEM team engineered LuxABCDEG to an E. coli-optimized biobrick

format, uncoupling it from the LuxR and LuxI regulation.

As a team we decided to work with this operon for a number of reasons, first of all, the luminescence

produced by this pathway is much more visually appealing than other systems from the registry (i.e XFPs),

moreover, the light production doesn´t depend on a single peptide but on a whole pathway involving several genes, which makes it much more tunable, for instance, decoupling in time the substrate recovery from the luciferase reaction itself.

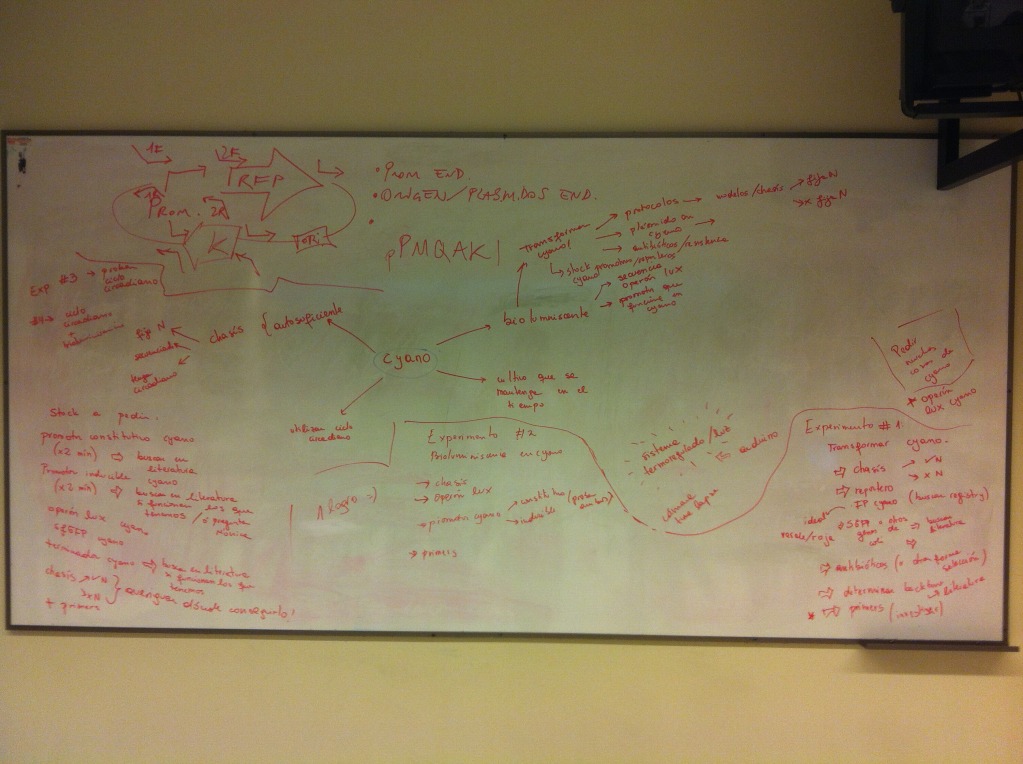

Experimental Strategy

We have devised different strategies to achieve bioluminescence controlled under circadian rhythms. Here we describe the strategies used for building the constructs to reach our goals.

Splitting the Lux operon and choosing promoters

We decided that we would separate LuxAB (the luciferase part of the operon) and LuxCDEG (the substrate producing enzymes LuxCDE with LuxG the FMNH2/FMN reducing enzyme) to allow phase-dependent expression of the parts. Using specific promoters of Synechocystis PCC. 6803 we can have fine-tunning of the production of bioluminescence. Recent work on global gene expression in Synechocystis aided on finding adecuate promoters 7, 8 . (Images at right from cited papers.)

To try our approach, we selected various promoters which could serve the purpose. Our rational for selecting candidate promoters involved amplitude of oscillation, peak activity, hour, absence of restriction sites, predicted strength of promoter according to the role of the gene and reproducibility between experiments (based on the literature available). We looked for promoters which would have peak expression nearby dusk hours and that were slightly out of phase to optimize production of bioluminescence according to our mathematical models (LINK OVER HERE!). We prioritized promoters from genes that would be involved in central energetic metabolism as we believe that their expression would be most robust and reliable.

We choose the transaldolase promoter (specific name here and code in Synechocystis Genome) to direct the expression of the LuxAB genes and we found a couple of other promoters which filled the other requirements from above. Pcaa3 (NAME HERE AND DESCRIPTION OF ENDOGENOUS ACTIVITY) and PsigE (NAME HERE AND DESCRIPTION OF ENDOGENOUS ACTIVITY), the former being already in Biobrick format (courtesy from the Utah team iGEM 2010).

Building constructs

When confronted with the different available strategies to express the genes from the Lux operon in Synechocystis, we concluded that the one that best suits our need is by using integration plasmids. The reason for this is that the available plasmids that replicate in Synechocystis are very large (8 Kb) without even considering the genes we need to include in the constructs (that would sum up to a final 16 Kb aproximately). Such a large plasmid would prove very difficult to handle through molecular biology techniques, let alone transform Synechocystis.

Using integration plasmids also proposes an additional advantage, that is to produce successive integrations which allow accumulation of different desirable elements in the genome. Integration in Synechocystis is undergone through double recombination of homologous DNA which also allows interruption of genes if wanted. In our case we have designed our system to produce suceptibility to copper as a biosafety measure to have further control over our recombinant Synechocystis.

We designed two constructs that have different recombination locations in the Synechocystis chromosome. We named them according to what Utah iGEM team from 2010 proposed for naming conventions:

pSB1C3_IntK

[http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K743006 BBa_K743006]

This construct is an integrative plasmid which targets neutral recombination sites (slr0370 and sll0337). We selected this locus because it has been extensively used in the literature ( 11) and it shown to have no deleterious effects on Synechocystis viability. We selected Kanamycin resistance as our selectable marker. [PUT LINK TO CONSTRUCT HERE].

Using this backbone we have decided to put LuxAB under the transaldolase promoter.We have choose the transaldolase promoter to express the luciferase part of the operon, as in the literature the promoter is described as having a peak of expression at 2 hours past dusk, which we believe is just the right timing to "turn on the lamp".

We've found 2 versions of the bacterial luciferase which we will use on this construct. The first one is of Photorhabdus luminiscent K216008 from the 2009 Edinburgh iGEM team and the second one is part from the LuxBrick (K325909 from the 2010 Cambridge iGEM team) and originally comes from Vibrio fisherii but has been "E.coli optimized".

pSB1A3_IntC (Utah 2010 iGEM Team integration plasmid)

We plan on using this plasmid to express the LuxCDEG contructs under the regulation of the Pcaa3 and PsigE promoters mentioned above. [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K390200 pSB1A3_IntC].

pSB1C3_IntS

Due to issues mentioned in the results page (PUT LINK HERE) we designed a new plasmid backbone.

This is an integration plasmid which makes Synechocystis susceptible to copper concentrations higher than 0.75 uM 10 by disrupting the CopS gene. We believe that this strategy serves as a biosafety measure to avoid the possibility of having a leakage of recombinant DNA to the environment. The plasmid uses Spectynomycin as a selectable marker. [PUT LINK TO CONSTRUCT HERE]

We plan on expressing LuxCDEG under the control of the promoters Pcaa3 and PsigE (mentioned above). These promoters have peak activities 1 hour before dusk. We believe that we might enhance bioluminescence yield initially by setting the substrate production/regeneration part of the operon prior to the expression of the luciferase.(LINK TO MODELLING?)

References

(1) Hohmann-Marriott MF, Blankenship.(2011). Evolution of photosynthesis. Annual Review of Plant Biology Vol. 62: 515-548

(2) Jonathan P. Zehr. (2011) Nitrogen fixation by marine cyanobacteria. Trends in microbiology, Vol. 19, 162–17

(3) Carl Hirschie Johnson and Susan S. Golden.(1999). CIRCADIAN PROGRAMS IN CYANOBACTERIA: Adaptiveness

and Mechanism. Annual Review of Microbiology, Vol. 53, 389-409

(4) Ducat, D. C., Way, J. C., & Silver, P. a. (2011). Engineering cyanobacteria to generate high-value products.

Trends in biotechnology, Vol. 29, 95-103.

(5) Huang, H.-H., Camsund, D., Lindblad, P., & Heidorn, T. (2010). Design and characterization of molecular

tools for a Synthetic Biology approach towards developing cyanobacterial biotechnology. Nucleic acids

research, 38, 2577-93.

(6) Peca, L., Kós, P. B., Máté, Z., Farsang, A., & Vass, I. (2008). Construction of bioluminescent cyanobacterial

reporter strains for detection of nickel, cobalt and zinc. FEMS microbiology letters, 289, 258-64.

(7) Kucho, K.-ichi, Okamoto, K., Tsuchiya, Y., Nomura, S., Nango, M., Kanehisa, M., Ishiura, M., et al. (2005).

Global Analysis of Circadian Expression in the Cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp . Global Analysis of Circadian

Expression in the Cyanobacterium. Society.

(8) Layana, C., & Diambra, L. (2011). Time-course analysis of cyanobacterium transcriptome: detecting

oscillatory genes. PloS one, 6, e26291.

(9) Kunert, a, Hagemann, M., & Erdmann, N. (2000). Construction of promoter probe vectors for

Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 using the light-emitting reporter systems Gfp and LuxAB. Journal of

microbiological methods, 41, 185-94.

(10)Giner-Lamia, J., Lopez-Maury, L., Reyes, J. C., & Florencio, F. J. (2012). The CopRS two-component system is responsible for resistance to copper in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant physiology, 159, 1806-1818.

(11)Kucho, K., Aoki, K., Itoh, S., & Ishiura, M., (2005). Improvement of the bioluminescence reporter system for real-time monitoring of circadian rhythms in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. Genes Genet. Syst. 80, p. 19–23

(12)Meighen, E. a. (1991). Molecular biology of bacterial bioluminescence. Microbiological reviews, 55(1), 123-42.

(13)Dunlap, P. V. (1999). Quorum regulation of luminescence in Vibrio fischeri. Journal of molecular microbiology and biotechnology, 1(1), 5-12.

(14)Luciferase, R. (2001). Differential Transfers of Reduced Flavin Cofactor and Product by Bacterial Flavin. Society, 1749-1754.

(15) Kelly, C. J., Hsiung, C.-J., & Lajoie, C. a. (2003). Kinetic analysis of bacterial bioluminescence. Biotechnology and bioengineering, 81(3), 370-8. doi:10.1002/bit.10475

(16)Tehrani, G. A., Mirzaahmadi, S., Bandehpour, M., & Laloei, F. (2011). Molecular cloning and expression of the luciferase coding genes of Vibrio fischeri. Journal of Biotechnology, 10(20), 4018-4023. doi:10.5897/AJB10.2363

"

"