Team:UC Chile/Results/Gibson

From 2012.igem.org

Contents |

Gibson Assembly for small parts

During the construction of our first plasmid, we had many problems dealing with getting correct assemblies of the constructs which involved small parts (< 200bp). We found that for those kind of assemblies, people would recommend different conditions. For example, some people recommended using as much as 5 times more DNA from the smaller insert in relation to the amount of plasmid backbone, arguing that such a small insert would be completely chewed up by the T5 exonuclease when in small amount. Others would recommend 1 to 1 mix of parts for Gibson Assembly. Because we did not find an authoritative source or consensus with respect to the optimal conditions for small part assembly, we decided to run tests under our experimental conditions.

Our analysis of the reaction gave us the notion that the number of resulting colonies would be in direct relationship to the amount of available backbone. However, the total number of true positives would only be influenced by the ratio at which the inserts could compete with the assembly of aberrant constructs, such as the one described by the Washington University 2011 iGEM Team about selfcomplementarity of the NotI sequences embedded in the prefix and suffix.

Considering that the small part would be degraded by the T5 exonuclease and that without insert available the remaining backbone would end up assembling with its selfcomplementary ends, we decided to evaluate whether by changing the amount of T5 exonuclease in the reaction we could improve our rate of true positives.

To test this hypothesis, we designed a Gibson Assembly which involved a small part of mRFP1 and a large backbone. Our design included a strategy to quickly identify those colonies which where true positives from false positives (i.e. RFP expression).

We used pSB4K5-J04450 and selected a fragment of mRFP1 which would measure 100bp plus the 40bp overhangs. Because this fragment is in the middle of the mRFP1, successful assembly would regenerate a complete mRFP1 gene making the colony visibly red.

We positioned the small mRFP1 fragment in such a way that if by any chance there was recircularization of the backbone, the resulting sequence would provide a helpful in-frame TAA stop codon to finish translation and evidence a false positive (i.e. no RFP expression).

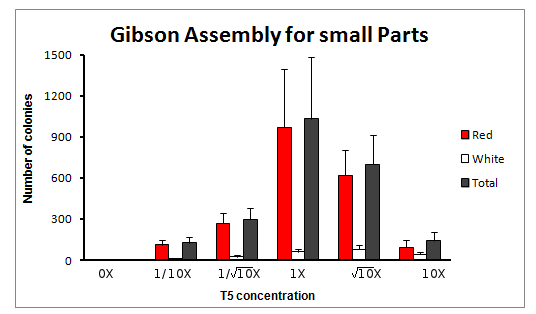

The experiment was done for 6 different concentrations of T5 exonuclease, in squareroot of 10 magnitude changes of the original T5 concentration. The concentrations were: 0X, 1/10X, 1/sqrt(10)X, 1X, sqrt(10)X and 10X T5 exonuclease.

Methods for the preparation of the experiment can be found in the protocols section.

Total count of colonies

We obtained different numbers of positive colonies with the different concentrations of T5 exonuclease in the Master Mix. As shown in the graph above, there is a clear maximum at 1x concentration of T5 exonuclease in the Master Mix.

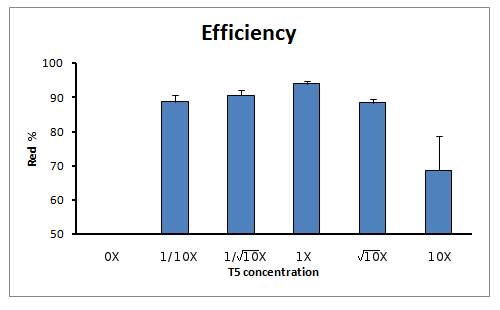

Efficiency of reaction

When calculating the efficiency of the reaction (in terms of true positive rate) we also see an increase of true positive rate towards the reaction with 1X concentration of T5 exonuclease in the Master Mix.

Conclusion

According to the results we obtained in this experiment we conclude that according to our DNA concentration conditions (0.00125 pmoles/uL) and ratio of insert to backbone (5:1), the Gibson Assembly reaction is already optimized for small parts of 140bp. Therefore, for assembling small parts we recommend to use 5:1 ratio of insert to backbone and Gibson Assembly reaction conditions as described in the Methods section. In addition, we think the methodology used in these experiments could help test additional conditions to standardize Gibson Assembly protocols in a time-efficient manner.

"

"