Team:Wageningen UR/InsideModification

From 2012.igem.org

Contents |

Inside Modifications

Introduction

Since virus-like particles (VLPs) lack genetic content, they enclose an empty space. This space can be filled with proteins such as antibiotics, hormones, and all sorts of pharmaceuticals. Modifications on the inside of the VLPs can increase binding affinity to the loaded substance. The first modifications we pursue is adding the K-coil to the protein subunits at any location that is exposed on the inside of the VLP. In our case, this is either a fusion to the N-terminus or to the C-terminus. The coils will facilitate strong attachment to the substance which has to carry the opposite coil.

The second modification we aim to make is a change in the interior's charge, which is another way to open up more options for loading our VLPs. Normally, the interior of a VLP is positively charged, facilitating interaction with negatively charged DNA/RNA molecules. By changing the amino acid sequence that is located on the interior of a VLP, the positive charge can be changed into a negative charge. A VLP with a negatively charged interior can be loaded with all sorts of positively charged molecules, such as polymeres, metal ions, etc.

Our aims:

- Construct a Virus-Like Particle that has K-coils exposed on the interior.

- Construct a Virus-Like Particle that has a negatively charged interior.

CCMV wt with a K-coil on the inside

The Cowpea Chlorotic Mottle Virus (CCMV) VLP is one of the best candidates for drug delivery, since it is tolerant of high temperatures and stable at a certain pH range. Next to that, the wild-type CCMV VLP is not specific for mammalian cells in vivo. Because of the promising properties of the CCMV VLPs, we decided to place coiled-coils on the interior. Since the N-terminus of the CCMV coat protein is folded to the inside of the VLP, this was the logic place to attach the coil. Attachment of coiled-coils allows the fusion of a range of molecules, which are immobilized on the inside of the VLP [1].

Methods

The attachment of the K-coil to the N-terminus of the CCMV wild-type VLP subunits was carried out in 4 subsequent PCR steps. To ensure the quaternary structure stability of both the CCMV wt capsid protein and the K-coil we placed a flexible linker between them. The flexible linker has following amino acid sequence LGGGGSGGGGSAAA and is reported to be separating two different protein domains effectively [2].

Unluckily, the primer of the first step was not designed correctly, resulting in a frameshift over the entire VLP, making this construct useless. We discovered this on the 18th of September, when receiving the sequencing results of a similar experiment the attachment of the Plug and Apply System to the outside of the CCMV Δ26 mutant.

Results

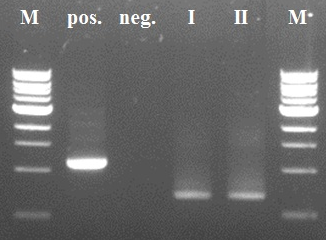

The first two steps of the PCR reactions went well. Except for the negative positive control of the first PCR step due to a pipetting mistake. We did the second PCR step with the PCR product of sample I (reasonably pure). The third and fourth PCR step of the experiment were redundant because of the wrong primer design in step I.

As mentioned before a mistake in primer design caused a serious frameshift resulting in a totally wrong translated protein (see figure 6)

Figure 5 shows the actual protein translation we wanted to achieve. The mistake was introduced in the annealing part of the first primer: FW1 FL-CCMV wt 5' TGGTGGTGGTTCTGGTGGTGGTGGTTCTGCTGCTGCTCCATGGGTACAGTCGGAAC 3'. These two marked basepairs, initially belonging to the wt CCMV sequence, should have been deleted in our selfmade fusion-protein because they are right in front of the START-codon (ATG).

CCMV with a negative interior

One of the modifications that was performed on the CCMV VLP was to give the interior a negative charge. Since the N-terminus of each of the 180 CCMV subunits is folded to the inside of the VLP, changing its charge would change the charge of the interior of the VLP completely. While the wild-type CCMV VLP can not be loaded with positively charged substances, this modified version can [3]. One very interesting feature of these modified VLPs is that they can be loaded with positive charged metal ions. Addition of iron ions to a solution containing these modified VLPs at a pH of 6.5 results in oxidative hydrolysis of the iron on the inside of the VLPs, creating paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles [3].

Methods

Constructing a CCMV VLP with a negative charge was facilitated by 3 subsequent PCR steps, see figure 8. Luckily this construct was finished in august and we were able to place an IPTG induced promoter combined with an RBS site in front of it. See labjournal.

Results

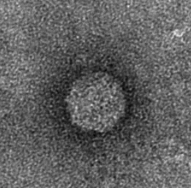

The next step was to produce VLPs with this new construct, which succeeded. The created biobricks are named [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K883160 BBa_K883160] & [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K883161 BBa_K883161]. VLPs were produced using BBa_K883161, which was at that moment present in the pSB1AK3 backbone in JM 109 cells. Protocols for growing the culture, dialysis of the VLPs and purifying the VLPs can be found here. In figure 8 a highly magnified image is shown of such a VLP with a negative interior. As a proof of concept, the CCMV VLPs with a negative interior were loaded with iron ions and monitored using electron microscopy. Unluckily, the samples were highly contaminated, which made it impossible to pinpoint any present VLPs. This contamination was possibly caused by the addition of iron to the samples. In figure 12 an image is shown of such a sample in which there is lots of contamination.

Hepatitis B with a K-coil on the inside

Deletions as well as modifications to the C-terminal of the Hepatitis B (HepB) core protein are possible since this part of the protein is not important for VLP formation [4]. Knowing this we can assume that the fusion of a K-coil to the C-terminal will lead to the formation of a VLP with a coil presented on the inside (figure 13).

To obtain the maximal amount of space in the VLP capsule we decided to delete a part of the C-terminal that is normally used for DNA binding and not required for VLP folding. After looking at protein folding predictions it was decided to add a short flexible linker between coil and core protein instead (see In silico folding prediction).

Methods

This modification was carried out in 4 PCR steps extending our construct one step at a time:

Results

After some problems with the last step of the PCR reaction a product with the correct length was obtained (see journal week 18). Unfortunately the ligation into a vector and transformation with E. coli did not succeed yet.

References

1. Minten, I.J., et al., Controlled encapsulation of multiple proteins in virus capsids. J Am Chem Soc, 2009. 131(49): p. 17771-3.

2. Arai, R., H. Ueda, et al. (2001). "Design of the linkers which effectively separate domains of a bifunctional fusion protein." Protein Eng 14(8): 529-532.

3. Douglas, T., et al., Protein Engineering of a Viral Cage for Constrained Nanomaterials Synthesis. Adv. Mater., 2002. 14, No. 6. March 18. p. 415-18.

4. Beterams, G., Böttcher B., & Nassal M. (15. Sept 2000). Packaging of up to 240 subunits of a 17 kDa nuclease into the interior of recombinant hepatitis B virus capsids. FEBS Lett., S. 169-76.

"

"