Team:Austin Texas/Caffeinated coli

From 2012.igem.org

Contents |

Project: Caffeinated Coli

Introduction

Caffeine is commonly used in foods and beverages such as coffee and chocolate and in pharmaceuticals as a cardiac and respiratory stimulant. As a result of the wide use of caffeine, it has become widely present in human waste and as a pollutant in the environment. Bacteria capable of degrading caffeine have been found naturally and could be used for bioremediation. We seek to port caffeine degradation functionality into Escherichia coli to produce strains that are better suited to degrade caffeine in an industrial setting.

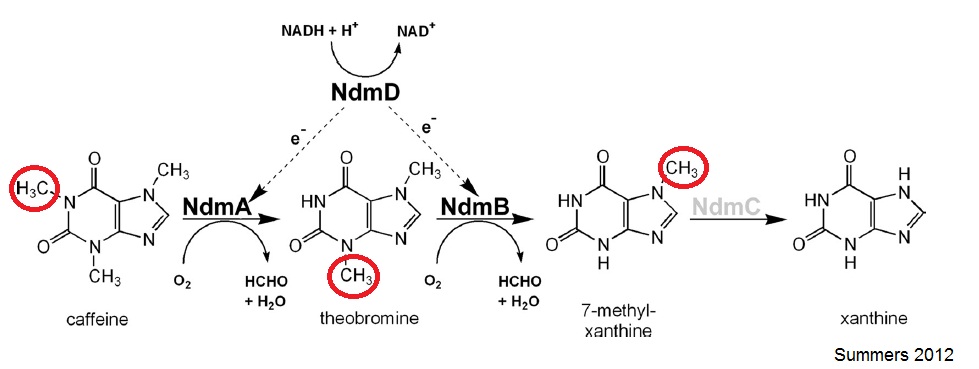

Pseudomonas putida CBB5, discovered by Ryan Summers and Mani Subramanian at the University of Iowa, can live on caffeine as the sole carbon and nitrogen source. CBB5 uses a Nitrogen demethylation pathway to convert caffeine to xanthine with formaldehyde side products. The xanthine and formaldehyde are then used as the nitrogen and carbon sources respectively.

The N-demethylation pathway consists of four demethylation genes: ndmA, ndmB, ndmC, and ndmD. ndmA, ndmB, and ndmC remove the methyl groups from the N-1, N-3, and N-7 respectively. This is done with the help of a reductase, ndmD.

<a href="http://cns.utexas.edu"> <a href="http://www.geog.ucsb.edu/events/department-news/1072/if-you-thought-fish-were-sleepless-in-seattle-check-out-the-ones-off-the-coast-of-oregon/">

Strategy

Refactoring Decaffeination Operon

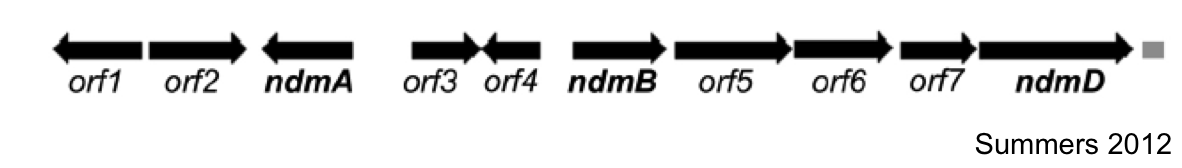

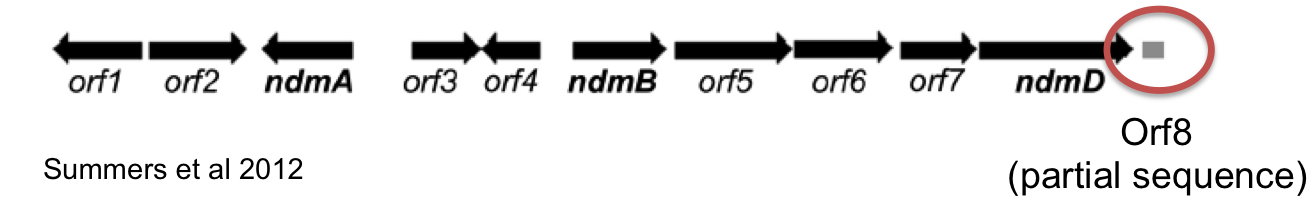

The first goal of this project involves refactoring the caffeine operon from the caffeine utilization pathway from Psuedomonas putida CBB5, first characterized by Summers et al. in early 2012. The operon, shown below, will be incorporated into the well characterized bacterium, Escherichia coli [3].

Directly importing the operon into E. coli was determined impractical, as the strength and regulation of the ribosome binding sites (rbs) and operon-controlled promoters in the CBB5 operon may not be optimized for function in E. coli. Additionally, the use in CBB5 of GTG start codons conflicts with E. coli’s preference for ATG – leading to problems in translation initiation.

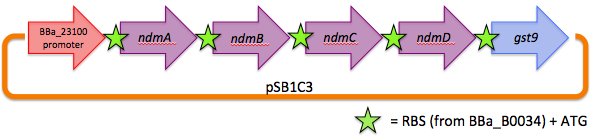

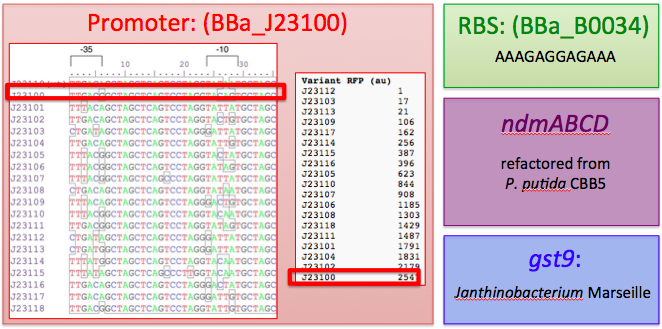

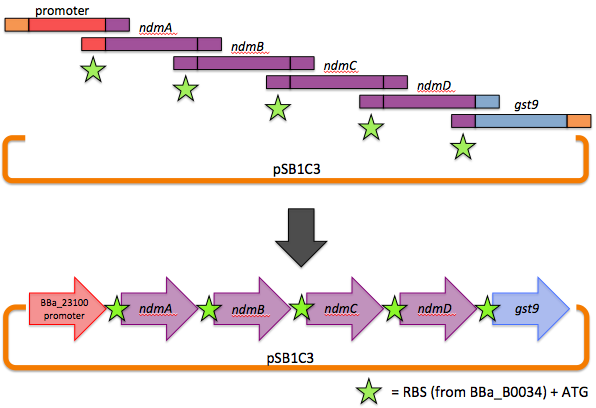

We therefore decided to separate out open reading frames for the genes of interest in the CBB5 operon and put them under controlled regulation in a refactored caffeine utilization operon for import into E. coli. The operon's design, shown below and submitted as [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K734000 BBa_K734000], aims to optimize its functionality in its new host.

This includes the N-demethylase proteins: ndmA, ndmB, ndmC, and the putative assisting protein ndmD. Also included is the glutathione S-transferase from Janthinobacterium sp. strain Marseille, necessary for functionality of NdmC. Constitutive expression occurs with a strong, well-characterized promoter ([http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_J23100 BBa_J23100]) and a strong, well-characterized RBS ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_B0034 BBa_B0034]). Finally, all GTG start codons have been replaced with ATG.

Sources of parts used in our synthetic decaffeination circuit:

Assembly

Our operon was assembled via a one-step, six-piece Gibson assembly. Briefly, genes to be stitched together were PCR amplified with overhangs homologous to adjacent genes (or homologous to the vector backbone in the case of the 5' end of the promoter and the 3' end of gst9). The forward primers also contained our chosen RBS and ATG. In a one-pot reaction, a 5'-exonuclease chewed back on the homologous overhangs, allowing adjacent fragments to base pair, and a DNA ligase stitched them together. An overview is shown here.

Operon Testing and Optimization

We will employ two different assays for operon functionality; growth on caffeine as a sole carbon source, and a genetic selection for caffeine demethylation to xanthine. To evaluate the ability to use caffeine as a sole carbon source we will transform TOP 10 E.coli electrocompetent cells with the refactored caffeine utilization operon, grow transformed cells in rich media to saturation and then dilute 1:100 into M9 mineral media. Varying levels of caffeine concentrations will be used to determine the degree of caffeine utilization, and the optimal limit for growth.

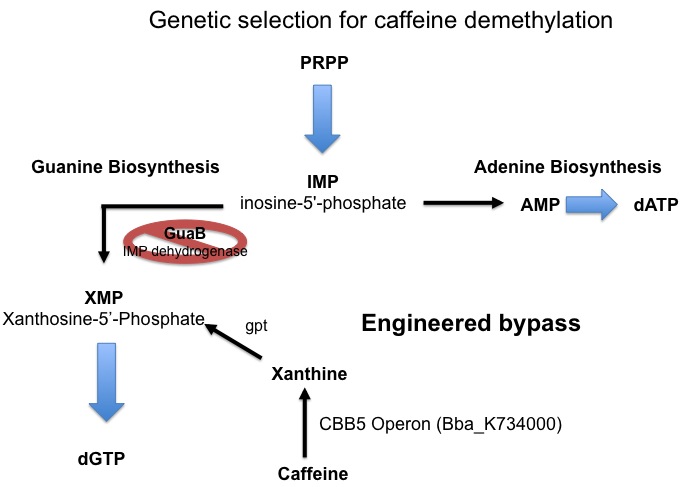

Since the cell has an extremely large requirement for carbon, the energy derived from demethylation may not be enough to support growth. For this reason a second assay for caffeine demethylation based on guanine auxotrophy has been devised. E. coli synthesizes the nucleotide guanine de novo via a pathway that involves Xanthosine-5’-phosphate (XMP) as an essential intermediate. The enzyme responsible for the formation of XMP (from inosine-5’-phosphate[IMP]) is IMP dehydrogenase, which is encoded by the GuaB gene. If GuaB is knocked out, the cell is unable to synthesize guanine and is therefore unable to grow on media lacking guanine. We plan to take advantage of this engineered auxotrophy and use it as a way to select for cells that are able to demethylate caffeine to xanthine which can then be converted to XMP by xanthine-guanine phosphoribotransferase (gpt) and thereby relieve the metabolic block and restore guanine synthesis allowing for cell growth.

Finally, after construction and preliminary testing of the caffeine degradation operon inE. coli, we will attempt to grow our cells in the presence of various commercial caffeinated beverages.

Characterizing Inducible Promoters

In Summers et al (2012)., the two open reading frames orf1 and orf4 are thought to be putative regulators of the caffeine degradation operon's N-demethylase proteins due to sequence homology to other known protein regulators (AraC and gntR family). They are hypothesized to bind to operator sequences in the intergenic regions between genes in the operon, which may serve as promoters for the various demethylases of the operon.

Analysis of the sizes of the intergenic regions of the CBB5 caffeine utilization operon shows that the regions upstream of the ndm genes are all greater than 150bp. The large size of these intergenic regions and the fact that they precede the catabolic enzyme gene leads us to hypothesize that there are caffeine (or other methylxanthine) regulatory elements in these sequences.

We will clone these open reading frames into the reporter plasmid pRA301. pRA301 contains a promoterless lacZ gene, preceded by a multiple cloning site (MCS). DNA fragments hypothesized to contain promoter elements can be cloned into the MCS and assayed for lacZ expression by Miller assay. Using this method, we can determine the regulatory functionality of each open reading frame by examining varying fluorescence levels.

CBB5 Genome sequencing

Since only a partial sequence (13.1kb) of the p.putida CBB5 decaffeination operon is available (Summers 2012), we are submitting genomic DNA for whole genome sequencing. The genome will be sequenced using Illumina next-gen sequencing by UT [GSAF]. The assembled genome will be deposited to Genbank.

Results

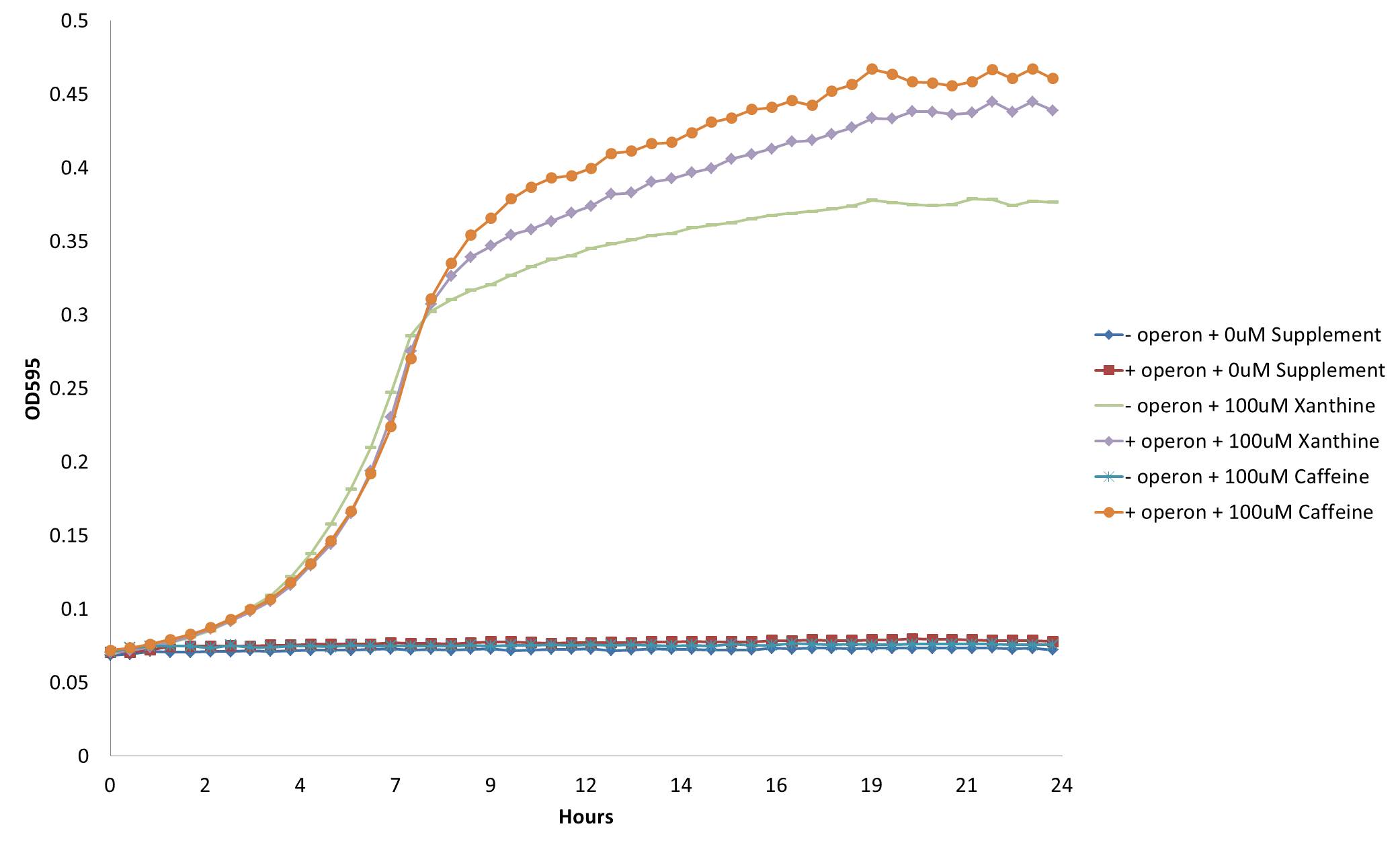

Decaffeination operon (+ gst9) enables growth of GuaB knockout

Our initial refactored operon consisted of CBB5 genes NdmA,B,C,D. We found that this operon was able to support growth of the GuaB knockout on theophylline but not caffeine. This indicated that the demethylase responsible for removing the 7-methyl group (NdmC) was not functional. Of note, Summers et. al (2012) also could not detect NdmC activity when expressed in E.coli. We reasoned that there could be a missing protein required for NdmC activity. Summers et al. (2012) showed that an uncharacterized protein (orf8) copurified in CBB5 protein fractions assayed for NdmC activity. We reasoned that this protein could be essential for NdmC function. Unfortunately, the complete DNA sequence of orf8 was not available; only a partial sequence of the orf was contained in the known operon sequence.

A protein homology search was performed using the available sequence to find potential homologs that might be able to substitute function of the missing orf. The search revealed that an uncharacterized gene, gst9, from Janthinobacterium marseille shared a high degree of sequence homology (70%). We decided to synthesize the gst9 gene from the available sequence and clone it into our decaffeination operon to see if it would enable NdmC activity and allow for complete demethylation of caffeine. We found our hyphothesis to be true, adding gst9 to our refactored operon [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K734000 (Bba_K734000)] did indeed enable growth of the guaB knockout on m9 mineral media:

From this figure, we see that our decaffeination operon enables the GuaB knockout to grow in the absence of guanine or xanthine supplementation by instead demethylating the available caffeine to produce xanthine. This not only confirms the functionality of our refactored decaffeination operon, but proves a method by which we can use it to auxotrophically select for cells.

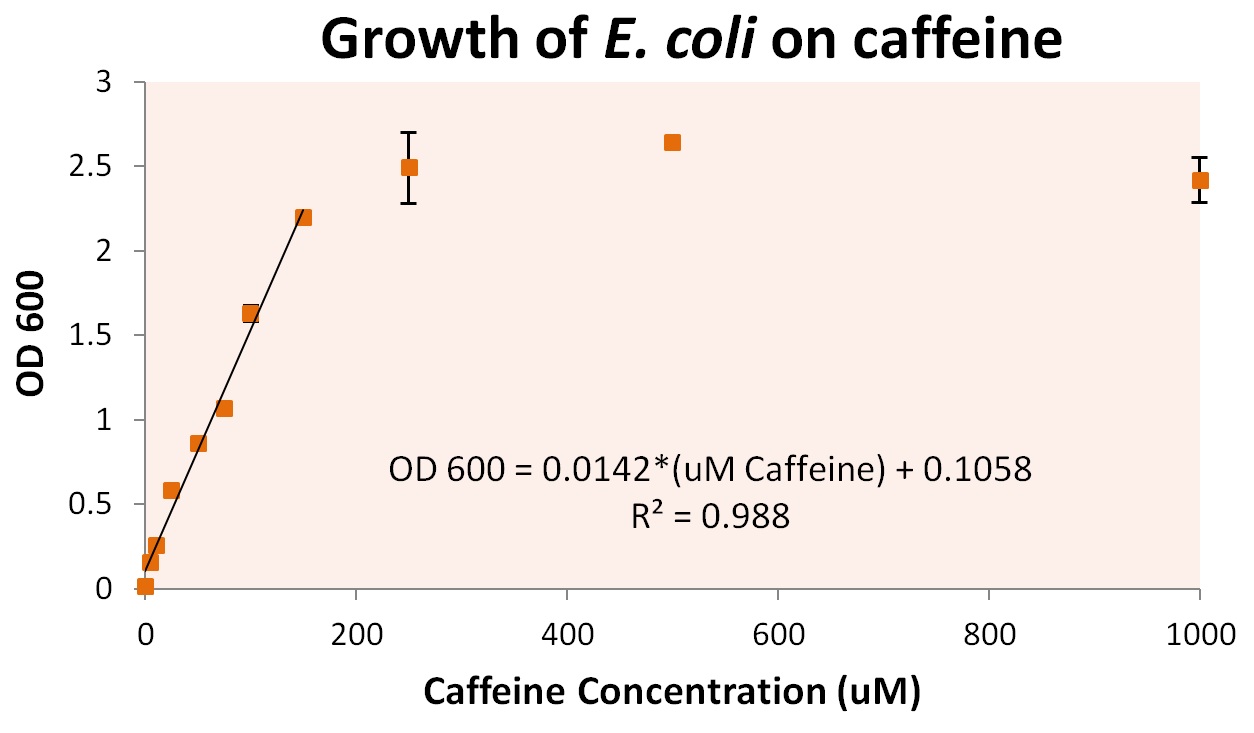

To more accurately determine the utilization of caffeine by our operon, we tested the growth of our E. coli cells containing refactored operon and the knocked out guaB gene under multiple caffeine concentration conditions. We found that our cells were able to grow at conditions as low as 10uM of caffeine, and peaked at a caffeine concentration of approximately 250uM. Cells were grown in concentrations as high as 5000uM, at which point cells began to die (presumably from caffeine toxicity).

From these growth conditions, we plated dilutions of up to 107 the concentration of original solution. This was used to determine individual cell growth based on caffeine. We discovered that approximately 7.6 +/- 0.8 pg of caffeine were utilized per cell. The graph above also shows a method by which we can convert directly from optical densities (an easily measured solution condition) to the caffeine concentration of the growth media. This is viable for cultures that contain cells with our refactored operon, and caffeine concentrations between 0 and approximately 250 uM.

Engineered E. coli stoichiometrically convert caffeine to guanine for cell replication

As caffeine appears to limit cell growth under these conditions, we were curious about how much of the provided caffeine was being utilized to create DNA and RNA for cellular replication. The genome of E. coli is roughly 4.6 Mb. Since this is double-stranded DNA and approximately 50% consists of G-C base pairs, there are about 2.3x106 guanines needed per cell to replicate its DNA. The dry weight of a typical E. coli cell is approximately 280 femtograms and 20% of this is RNA ([http://bionumbers.hms.harvard.edu Bionumbers]). Given the molecular weight of a typical RNA nucleotide is roughly 330 g/mol, and that 1/4 of these bases are guanine, this means that there are about 2.55x1010 guanines needed per cell to replicate its RNA. So, overall the number of guanine molecules in RNA is roughly 10,000x the amount in DNA.

We found that 7.6 +/- 0.8 pg of caffeine was utilized per cell. Given the molecular weight of 194.19 g/mol, this translates into 2.4x1010 molecules of caffeine per cell. This is in amazing agreement with the number of molecules of guanine that we have calculated that is required to replicate a cell!

| Molecules of Guanine (g/L) | |

|---|---|

| Scavenged by Cells from Caffeine | 2.40x1010 |

| Theoretically Required for Replication | 2.55x1010 |

Growth in Caffeinated Beverages

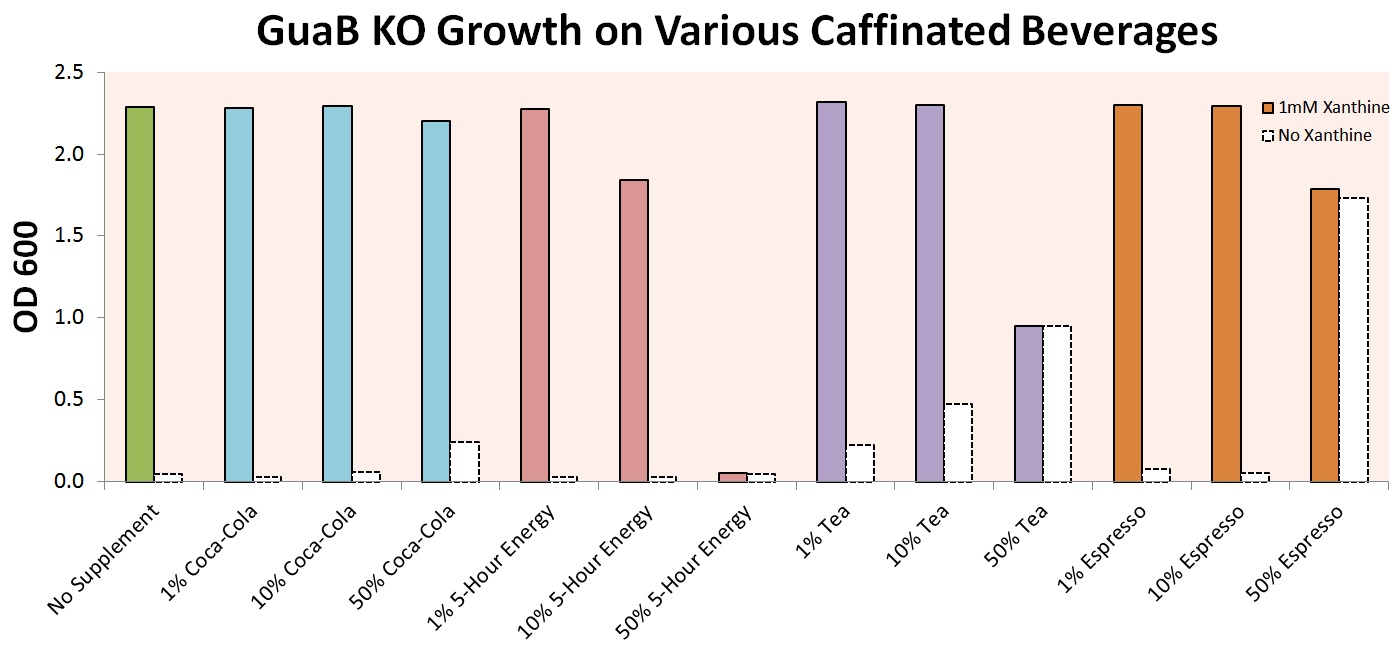

In order to make our experiment more relatable, we experimented with growth of our E. coli strain in various caffeinated beverages. Experiments were first performed on cells with only the GuaB knockout modification, in order to prove that growth in these beverages was even possible. Initial results, shown below, indicate that growth is in fact possible for a wide variety of beverages, including Coca-Cola, 5-Hour Energy, Lipton Tea, and Startbucks Espresso.

The graph above shows that the auxotrophic selection of cells using xanthine derivatives again functions as expected – without xanthine, cells were unable to grow under most conditions. The noticeable Optical Densities for 50% Coca-Cola and 50% Espresso are due to the strong background color of the culture and not actual cell growth. 50% 5-Hour Energy and Espresso were both shown to be toxic to our cells. Finally, tea was shown to contain enough natural xanthenes to allow for partial cell growth, and was excluded from further experiments.

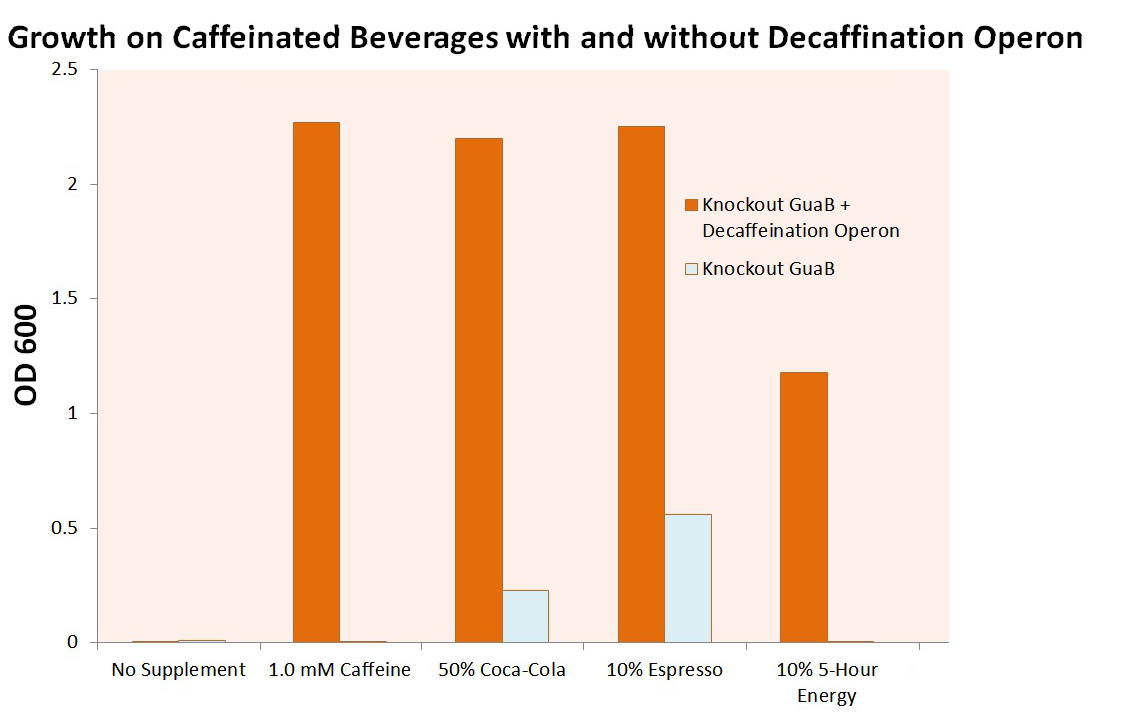

We then attempted to grow our cell strain containing both the GuaB knockout gene and the refactored decaffeination operon. The results of this experiment are shown below.

It is important to note that these cells were grown in M9 minimal media containing only 0.2% casein as a natural carbon source. The cells were required to scavenge virtually all of their carbon required for guanine synthesis from the caffeine supplied to the system, or die. Our E. coli was able to utilize the caffeine inherent to Coca-Cola, Starbucks Espresso and 5-Hour Energy, as well as caffeine in caffeine. However, without our refactored decaffeination operon, the cells were unable to grow under any conditions. The two small bars that appear above in 50% Coca-Cola and 10% Espresso are simply due to the high background color of the cultures. It is also worth note that the 10% 5-Hour Energy growth conditions proved marginally toxic to our E. coli cells, as the cells were unable to reach maximum Optical Densities.

Utilizing the previous experiment in which we calculated the growth of our cells per caffeine molecule, we are able to estimate the total concentration of caffeine in each of the original caffeinated beverages. This is done by fitting the created equation that converts OD into predicted caffeine concentration. From caffeine concentration and the known dilution of caffeinated beverage added to each of the cultures, we can estimate the caffeine weight per beverage volume. These results are summarized below, and are very close to the values determined by the beverage manufacturers themselves. This serves as further reinforcement that our decaffeination operon works as intended, and even suggests a possible use in measuring the caffeine value of beverages. Note that the cells in 5-Hour Energy appeared to be in exponential growth phase, weakening the strength of the equation's fit to reality.

| Caffeine Content we Calculated (g/L) | Caffeine Content Manufacturer Calculated (g/L) | |

|---|---|---|

| Coca-Cola | 99.1 | 98.6 |

| Starbucks Espresso | 44.7 | 39.5 |

| 5-Hour Energy | 4259.8 | 2333.2 |

Finally, we took pictures of our cells grown in caffeinated beverages cultures, as shown below. Cells in the left tubes do not contain the decaffeination operon, while cells in the right tubes actually do contain the decaffeination operon. Both contain the GuaB operon knocked out, and require xanthine or xanthine derived from caffeine in order to survive. As shown below, Coca-Cola, Diet Coke and Coffee, all of which contain caffeine, feature strong growth of the guaB knockouts with the decaffeination operon. However, Caffeine Free Diet Coke shows no growth even with the operon, as there is no caffeine to be used as a xanthine source.

Transcriptional Regulators

As described earlier, we hypothesize that the large intergenic regions upstream of various genes in the CBB5 decaffeination operon, particularly upstream of ndmA, may contain methylxanthine regulated promoters. We propose that orf1 and orf4, which were annotated as putative regulators based on sequence homology, act as repressors for the promoters contained in the operon.

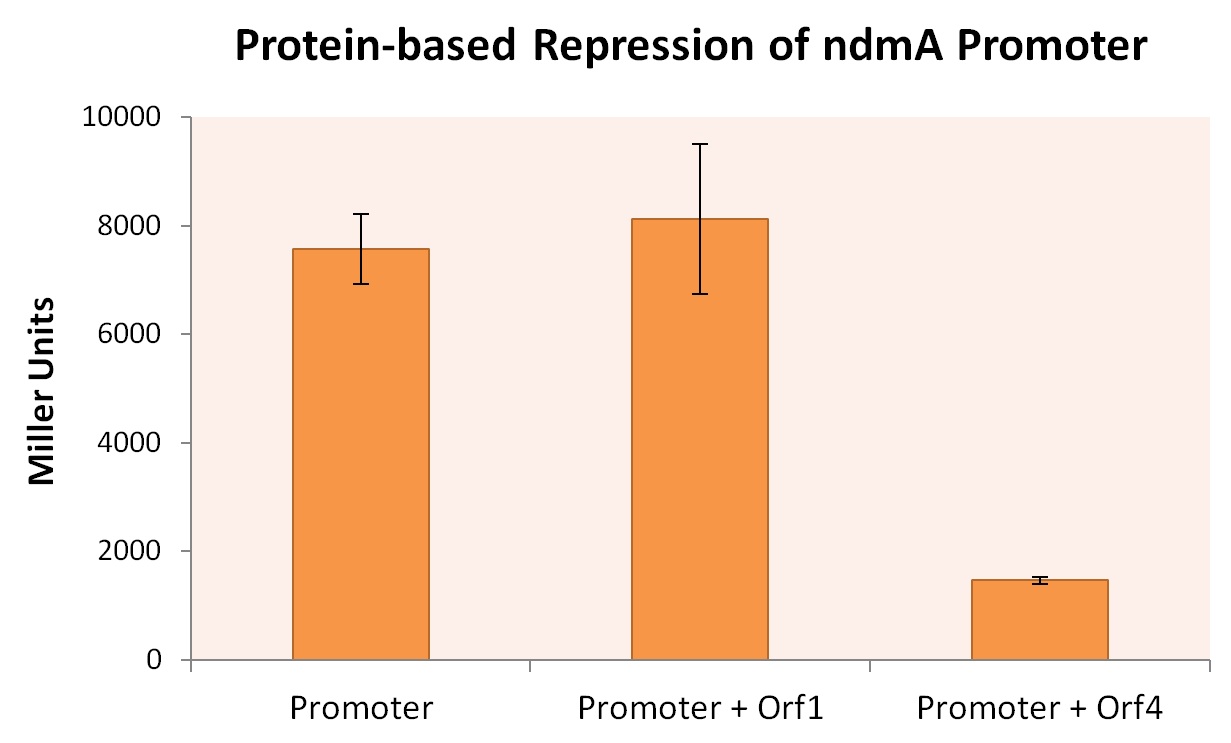

To test these hypotheses, we cloned the intergentic region upstream of the ndmA gene into a promoterless LacZ reporter plasmid, pRA301. This vector enabled quantitative measurement of promoter strength using the β-galactosidase Miller Assay. Additionally, we created compatible biobrick plasmids of each putative repressor, orf1 and orf4, in order to assay their effect on ndmA promoter strength in the presence or absence of methylxanthine supplementation.

We transformed these plasmids into the Top10 E.coli strain to create three strains: one containing only the ndmA-LacZ reporter plasmid, and cotransformants containing both the ndmA-LacZ plasmid and either orf1 or orf4 biobrick plasmids. All three E. coli strains were grown in M9 minimal media + .2% casein (+ appropriate supplement) at 30oC for 48 hrs, after which time Miller assays were performed. The results, summarized in the figure below, provide strong evidence that expression of orf4 leads to inhibited ndmA promoter functionality, while orf1 expression provides negligible influence on the ndmA promoter.

A higher Miller Unit correlates to a higher level of lacZ production, effectively quantifying the degree of gene expression. As the Miller Unit of the strain co-expressed ndmA promoter with orf4 is lower by a factor of roughly 4, it can be inferred that the protein encoded by orf4 regulates the degree to which the ndmA promoter is expressed during transcription.

It should be noted that while expression of ndmA drops significantly in this experiment, this does not imply that orf4 only inhibits the expression of ndmA. This is discussed in the next section: Inducible Promoters.

Inducible Promoters

As shown above, it appears that orf4 acts as a transcriptional regulator of ndmA expression. One would expect a transcriptional regulator to regulate transcription in a way that is beneficial to the overall fitness of the organism. In certain situations in which a protein is necessary for survival, the transcriptional factor should up-regulate the production of said gene. Likewise, when a protein is not necessary, the transcriptional factor should down-regulate its production.

We hypothesize that this is the way in which orf4 regulates transcription of ndmA. In situations of high caffeine and related xanthine concentrations, the protein encoded by orf4 up-regulates the expression of ndmA. In the experiment listed above, in which no xanthine derivative was added to the media, expression from the ndmA promoter is inhibited (as shown).

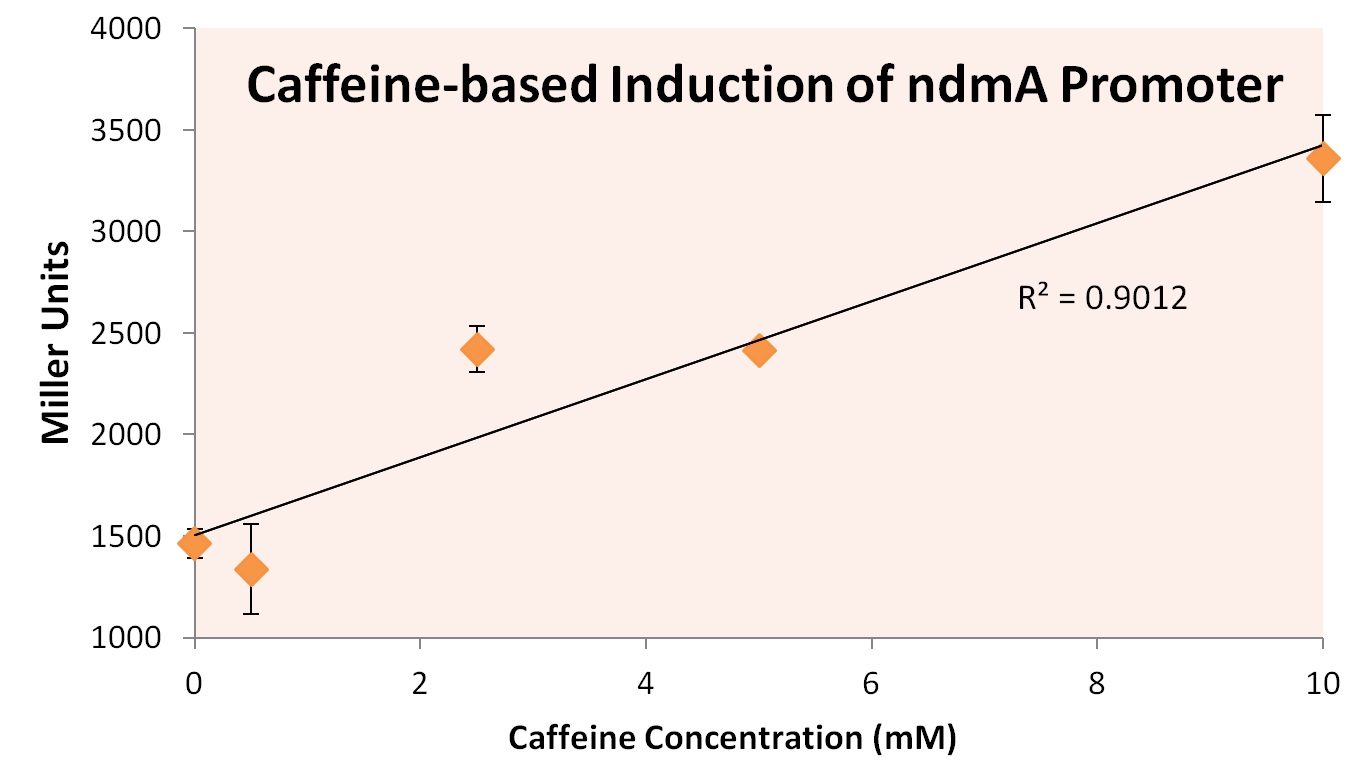

In order to test this hypothesis, we subjected a strain of Top10 E. coli cells containing the orf4 gene and the ndmA promoter containing the lacZ gene to varying supplements of caffeine, theobromine, theophylline, and xanthine. Xanthine was shown to be insoluble at high concentrations, and was therefore removed from the experiment. The results of exposure to varying concentration levels is shown below.

As predicted, the expression of ndmA appears to rise at higher caffeine concentrations. Similarly, higher concentrations of theobromine and theophylline also appear to increase the expression of ndmA.

From these experiments we conclude that the ndmA intergenic region contains a promoter that is negatively-regulated by the orf4 protein in the absence of methylxanthines. Upon exposure to methylxanthines, it appears that orf4-mediated repression is relieved, leading to induction.

Results Summary

The main accomplishments we achieved this Summer include the following:

- Refactoring of decaffeination operon from P. putida into E. coli

- Construction of an auxotrophic selection method using our refactored operon, "addicting" E. coli to caffeine

- Growth of auxtrophic cells on common caffeinated beverages

- Discovery of a methyxanthine inducible promoter (ndmA) in the CBB5 operon

- Characterization of an open reading frame (orf4) in the CBB5 operon that acts as a transcription regulator

References

Summers RM, Louie TM, Yu CL, Gakhar L, Louie KC, Subramanian M, "Novel, highly specific N-demethylases enable bacteria to live on caffeine and related purine alkaloids." Journal of Bacteriology, 2012, vol 194, no 8, pg 2041-2049.

Rodriguez del Rey Z, Granek EF, Sylvester S, "Occurrence and concentration of caffeine in Oregon coastal waters." Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2012, vol 64, no 8, Pages 1417-1424.

"

"