Team:TU Munich/Project/Brewing

From 2012.igem.org

Nadine1990 (Talk | contribs) (→Experiment 1: Survival and growth of different yeast strains under various conditions) |

VolkerMorath (Talk | contribs) (→Preparation of the Mash) |

||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

#'''(1A)''' We started by filling 20 l of water in a steel pot and heated it up to about 50 °C and then added 4-5 kg malt. If you are in possession of a special bag for mash, a so called "Maischesack", you can fill the malt in the bag and hang it into the pot. Mind that the bag should not touch the bottom of the pot as this could lead to burning of the bag and results in a slightly burned taste. | #'''(1A)''' We started by filling 20 l of water in a steel pot and heated it up to about 50 °C and then added 4-5 kg malt. If you are in possession of a special bag for mash, a so called "Maischesack", you can fill the malt in the bag and hang it into the pot. Mind that the bag should not touch the bottom of the pot as this could lead to burning of the bag and results in a slightly burned taste. | ||

| - | #'''(1B)''' We kept up the temperature of 50 °C and continuously stirred the mixture for 30 minutes. During these 30 minutes proteases will decompose proteins contained in the shredded malt. After those 30 minutes we heated the mixture to 63 °C and kept this temperature up for 60 minutes. Subsequently we heated to 73 °C and kept stirring continuously. [[file:TUM12_Beer_degree_determ.png|300px|right|thumb|'''Figure 3.''' Measurement of original wort]] [[file:TUM12_Beer_iodine.png|300px|right|thumb|'''Figure 4.''' A) Still starch available so it is not finished now B-C succeeding samples from an iodine test]] | + | #'''(1B)''' We kept up the temperature of 50 °C and continuously stirred the mixture for 30 minutes using a stirring device (IKA, Staufen, Germany). During these 30 minutes proteases will decompose proteins contained in the shredded malt. After those 30 minutes we heated the mixture to 63 °C and kept this temperature up for 60 minutes. Subsequently we heated to 73 °C and kept stirring continuously. [[file:TUM12_Beer_degree_determ.png|300px|right|thumb|'''Figure 3.''' Measurement of original wort]] [[file:TUM12_Beer_iodine.png|300px|right|thumb|'''Figure 4.''' A) Still starch available so it is not finished now B-C succeeding samples from an iodine test]] |

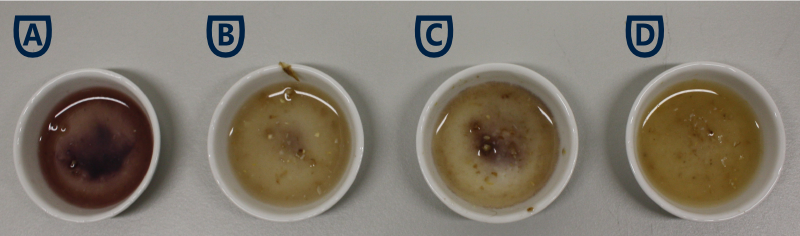

#'''(1C)''' The next step was the iodine test to verify whether starch was completely converted to sugar. We removed a small sample of mash and added iodine. A resulting blue-violet coloring indicated that there was still some leftover starch so the temperature of 73°C was kept up and this step was repeated until no staining was visible.<br> As soon as the iodine did not cause any stain the mash was heated to 78 °C for 90 minutes - again under continuous stirring. | #'''(1C)''' The next step was the iodine test to verify whether starch was completely converted to sugar. We removed a small sample of mash and added iodine. A resulting blue-violet coloring indicated that there was still some leftover starch so the temperature of 73°C was kept up and this step was repeated until no staining was visible.<br> As soon as the iodine did not cause any stain the mash was heated to 78 °C for 90 minutes - again under continuous stirring. | ||

#'''(1D/E)''' The next step in the procedure was the lautering: a lautering cloth was strained over the opening of a large plastic pot and all the mash was filtered through this cloth. As all the malt was filtered out in this step the lautering cloth needed to be well fixated to the plastic pot as it was needed to carry weights of up to 5 kg. | #'''(1D/E)''' The next step in the procedure was the lautering: a lautering cloth was strained over the opening of a large plastic pot and all the mash was filtered through this cloth. As all the malt was filtered out in this step the lautering cloth needed to be well fixated to the plastic pot as it was needed to carry weights of up to 5 kg. | ||

Revision as of 14:01, 8 April 2013

Contents |

Brewing

Contrary to popular opinion the chief ingredient of beer is not YPD but gyle, a carefully prepared mixture of malt, hop and water. Although the name of the yeast strain commonly used in the lab, S. cerevisiae, suggests that it is used in the beer brewing process, the yeast strains generally employed in brewing process have strongly adapted to gyle, as they are reutilized after every succeeding brewing cycle. Hence some investigation on how our yeast performs in gyle was necessary.

Our experiments show that the growth of several different yeast strains is not impaired in gyle!

Expression assays proved the necessity of genome integration for a proper SynBio Beer.

The Brewing Process

Preparation of the Mash

- (1A) We started by filling 20 l of water in a steel pot and heated it up to about 50 °C and then added 4-5 kg malt. If you are in possession of a special bag for mash, a so called "Maischesack", you can fill the malt in the bag and hang it into the pot. Mind that the bag should not touch the bottom of the pot as this could lead to burning of the bag and results in a slightly burned taste.

- (1B) We kept up the temperature of 50 °C and continuously stirred the mixture for 30 minutes using a stirring device (IKA, Staufen, Germany). During these 30 minutes proteases will decompose proteins contained in the shredded malt. After those 30 minutes we heated the mixture to 63 °C and kept this temperature up for 60 minutes. Subsequently we heated to 73 °C and kept stirring continuously.

- (1C) The next step was the iodine test to verify whether starch was completely converted to sugar. We removed a small sample of mash and added iodine. A resulting blue-violet coloring indicated that there was still some leftover starch so the temperature of 73°C was kept up and this step was repeated until no staining was visible.

As soon as the iodine did not cause any stain the mash was heated to 78 °C for 90 minutes - again under continuous stirring. - (1D/E) The next step in the procedure was the lautering: a lautering cloth was strained over the opening of a large plastic pot and all the mash was filtered through this cloth. As all the malt was filtered out in this step the lautering cloth needed to be well fixated to the plastic pot as it was needed to carry weights of up to 5 kg.

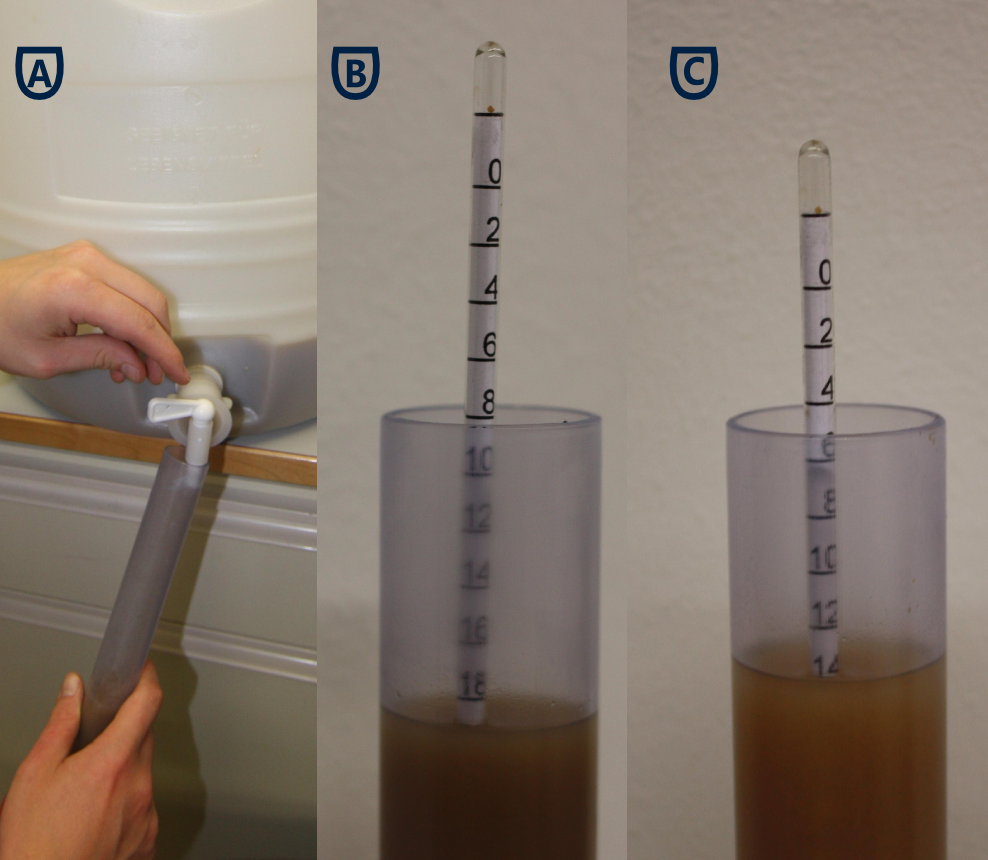

- (3A-C) The filtrate, the so called gyle, should now have a wort of about 12 %. The wort was measured with the help of a refractometer or a hydrometer. If the target of 12 % could not reached, hot water should be filtered through the mash and the lautering cloth until 12 % wort are attained.

- (1F) Eventually the mash should be filled back into the steel pot, after carefully cleaning it.

Brewing the beer

- After heating the gyle to 100 °C, 30-40 gram of hops were added. The best results were obtained when the hop was not directly added to the gyle but filled in a small bag with small stones and then thrown into the gyle.

- The temperature of 100 °C should be kept up for 60 minutes. During this time the plastic pot should be cleaned and sterilized. The lautering cloth should also be cleaned, using boiling water.

- Now another filtration step was necessary which was exactly the same as step 4 above although this time every utensil employed needed to be kept sterile.

- The plastic pot should now been stored in a cold place where the gyle could cool down. Speeding up this procedure as long as the gyle was kept sterile was highly advised.

- The following steps depend heavily on type of yeast that will be used.

- As S. cerevisiae is a bottom-fermenting yeast the gyle should have a temperature of about 10 °C. From now on all temperatures should be checked regularly as heat is generated during the fermentation process.

- When the target temperature was attained the yeast was added and the gyle was stirred to homogeneously spread the yeast in the gyle. The plastic pot was closed with a cap (not air-tight!) and was stored for 24 h at about 20 °C.

- When working with a fermenting tube it should now be attached to the cap and filled with boiling water. This should close the pot air-tight.

- Now the beer should be stored for 8-11 days until no more bubbles are visible on top of the gyle. This will conclude the brewing process.

- The finished beer can now be filled in bottles. Pay attention that no yeast is dispersed from the bottom of the pot! When working with transgenic yeast, sterile filtering should be used to assure that no transgenic yeast enters the bottle!

Results

Experiment 1: Survival And Growth of Different Yeast Strains under Various Conditions

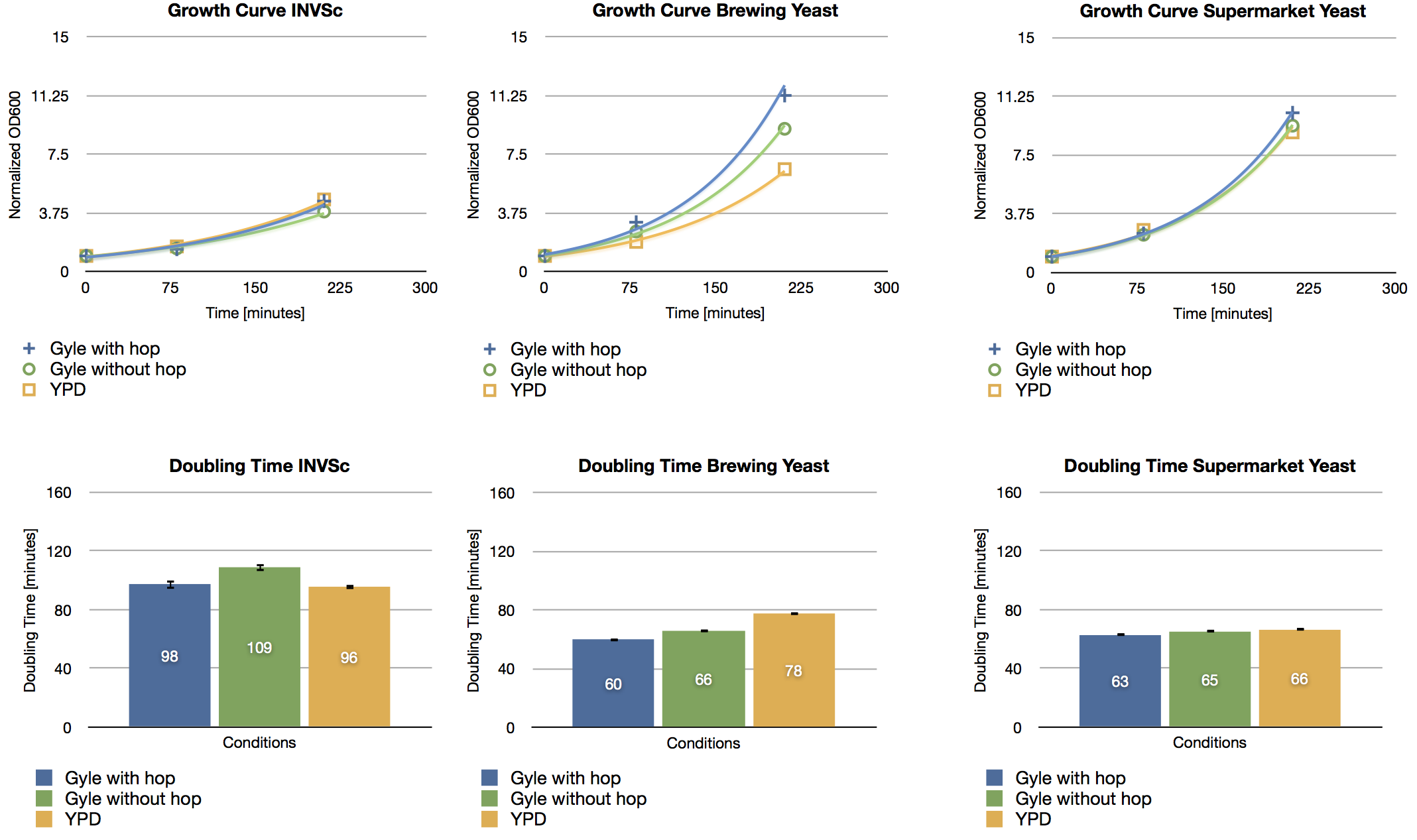

To ensure that our yeast strain INVSc grew in a medium which is typical for the brewing process we set up an experiment with different conditions.

We compared the growth rate of the laboratory yeast INVSc to a yeast strain, which is typically used for brewing beer and to a yeast strain, which can be purchased at normal supermarkets. We inoculated those three strains with the same OD in three different mediums: gyle with and without hop, and the typically laboratory medium YPD, which we used for all our expression experiments. The growth rate was measured after a defined time period by measuring the OD at 600 nm.

The results show no difference in growth behavior. Neither the three different strains grew unequally in the same medium, nor the various mediums had an effect on the growth rate of the yeast strains. This experimental proof of principle shows the ability of our genetically modified yeast to grow in the given environment in an adequate amount we needed for our experiments. Hence we did not need to switch to a specialized brewing yeast for our brewing experiments.

Experiment 2: Experiments with Expression Cassettes on A Transient Transfected Vector

A first attempt to use our genetically engineered yeasts to brew a SynBio Beer was conducted using a transient transfection with a constitutive promoter. The drawback is that in gyle the selection pressure was not preserved and the loss of the plasmid was possible.

Three liters of gyle were inoculated in 100 ml of a stationary yeast culture grown in YPD that was transiently transfected with a plasmid harboring a constitutive expression cassette for the limonene synthase.

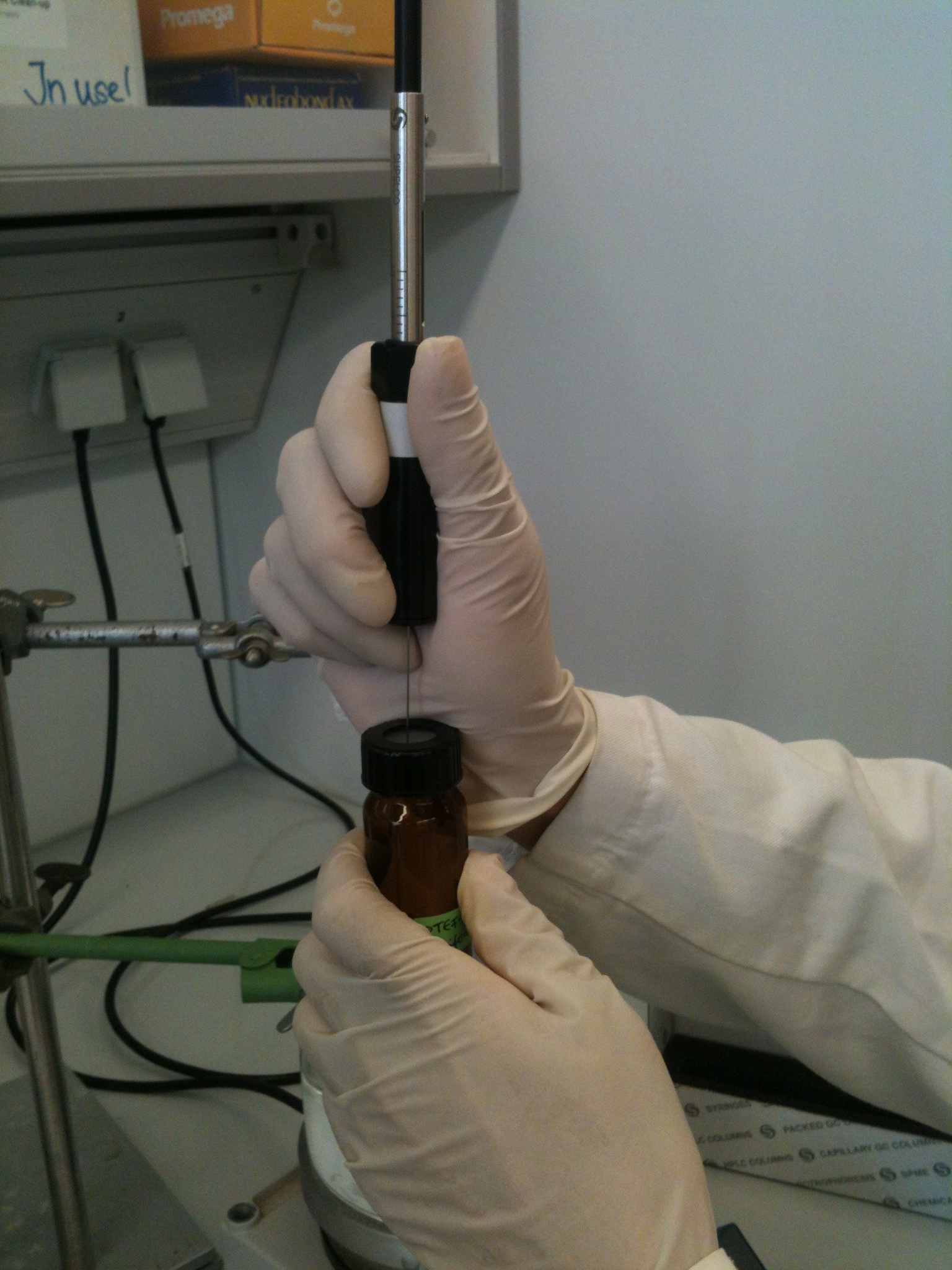

We analyzed this first beer for limonene content via headspace (SPME needle) GC-MS. Unfortunately, we could not yet proof a significant difference between the beer containing limonene and the negative control beer. This might be due to a loss of the plasmid which encodes limonene synthase. We will try to integrate the limonene synthase expression cassette into the genome of yeast and afterwards we will repeat the experiment.

"

"