Team:Wageningen UR/HumanBody

From 2012.igem.org

MarkvanVeen (Talk | contribs) (→Results) |

MarkvanVeen (Talk | contribs) (→Results) |

||

| Line 96: | Line 96: | ||

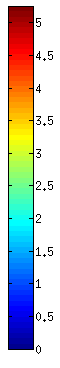

|[[File:VLPconcWITHMED.png|400px|left|thumb|"Figure 3: x-axis: time in minutes, y-axis: concentration in µmol. Concentration over time of VLP within the human body according to the model. "]] | |[[File:VLPconcWITHMED.png|400px|left|thumb|"Figure 3: x-axis: time in minutes, y-axis: concentration in µmol. Concentration over time of VLP within the human body according to the model. "]] | ||

|<html><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2012/b/ba/Vlp_gif_opt.gif" alt="VLP MED"></html> | |<html><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2012/b/ba/Vlp_gif_opt.gif" alt="VLP MED"></html> | ||

| - | |[[File:VLPbar.png|400px|left|thumb]] | + | |[[File:VLPbar.png|400px|left|thumb|Border=0]] |

|- | |- | ||

Revision as of 18:44, 26 October 2012

Contents |

Human Body Model

To be able to determine what the VLPs and the medicine do in the human body we have constructed a human body model that is inspired by the model of the Slovenia 2012 team. With this model we are able to compare the traditional use of medicine with the use of our VLPs. If successful it will open up a whole new era for the use of medicine.

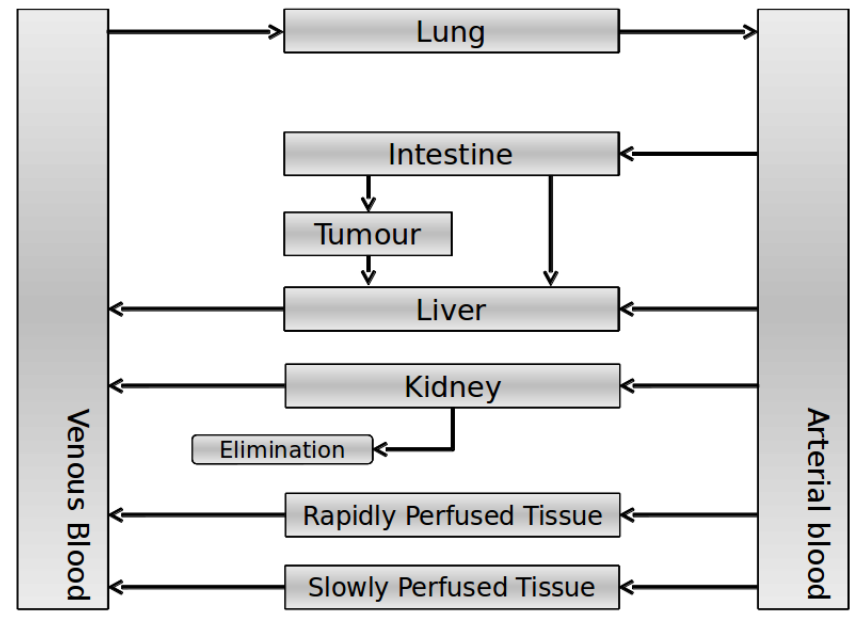

Explanation of the model

Our model is constructed in such a way that each compartment of the model represents an organ or multiple organs with the same physical properties. We decided to have separate compartments for the kidneys, liver, lungs and the intestine. All other organs are grouped in the rapid or slowly perfused tissue. In the case study we made a new compartment between the intestine and the liver to represent the intestine tumor (figure 1).

In our model we have used three different mass balance equations for an organ. The first mass balance describes the concentration of all the VLPs in the organ, this is to see the overall change in the VLP concentration. The second mass balance equation describes the concentration of the unbound VLPs. This is because the unbound particles can move freely into the body while the bound particles stays into the organ. The final mass balance equation is for the concentration of the medicine in the organ. With these three mass balance equations we’ve developed our model. At the botom of the page the model can be studied intensivly.

Case study: colorectal cancer

As our case study to use the human body model, we used colorectal cancer. Cancer as a disease is very destructive and is responsible for the deaths of millions. In 2007, 13% of all the deaths were cancer related [1]. We chose colorectal cancer because in Europe the 5 year survival the disease is less than 60% [2]. If our treatment shows a better treatment we can help the people to fight off the cancer.

Treatment of Colorectal cancer

The conventional way to treat colorectal cancer includes surgery and chemotherapy if the cancer is detected in an early stage, when it detected in a later stage treatment is often directed more at extending life and keeping people comfortable [2]. The agents used for chemotherapy are fluorouracil, capecitabine, UFT, leucovorin, irinotecan, or oxaliplatin. Side effects [3] of the agents are:

- Acute central nervous system damage

- Bone marrow suppression

- Mucositis, inflammation of the mucus membranes of the GI track

- Dermatitis, inflammation of the skin

- Diarrhoea

- Nausea

- and many more

We believe, if we can focus the agents around the tumor we’ll able to reduce the side effect and create a better chemotherapy treatment for cancer patients.

Parameters

For the distribution of VLPs throughout the human body, used parameters were obtained from the documentation Slovenia 2012 or from literature sources [4]. The estimated parameters for the organs in table 1 are explained as followed: Blood-flow, the amount of blood in liters flushing throughout the organs, Volumes, the size of the organ, Receptor, the concentration of receptors in µM and the partition coefficient of the medicine that is packaged within the VLP.

| Organ | Blood-flow [L/min] | Volume [L] | Receptor 1 [uM] | Partition coefficient medicine |

| Rapidly perfused tissue | 1 | 3.61 | 0.237 | 100 |

| Slowly perfused tissue | 2.12 | 53.2 | 0.237 | 100 |

| Kidney | 1.06 | 0.31 | 0.237 | 100 |

| Liver | 1.4 | 1.82 | 0.237 | 100 |

| Lung | 5.58 | 0.56 | 0.237 | 100 |

| Intestine Healthy | 0.94 | 4.41 | 0.237 | 100 |

| Tumor | 0.1 | 0.49 | 10.716 | 100 |

| Arterial | 5.58 | 1.7 | 0.237 | 100 |

| Venous | 5.58 | 3.9 | 237 | 100 |

Parameters that were estimated for non organ variables are found in table 2 and are explained as followed. Affinity constant for receptor, is the binding affinity of the VLPs to the receptor on the cell surface. VLP elimination rate is the half-life of the VLPs. VLP Renal removal rate is the removal rate of the VLPs within the kidneys [5]. Medicine elimination rate is the removal/degradation of the medicine within the human body [6]. The last parameter is the packaging constant which encapsulate the amount of medicine in µmol within a single VLP.

| Affinity constant for receptor | 0.001 |

| VLP elimination rate | 0.000143 |

| VLP Renal removal rate | 0.000403 |

| Medicine elimination rate | 0.05 |

| Packaging constant | 300 |

Results

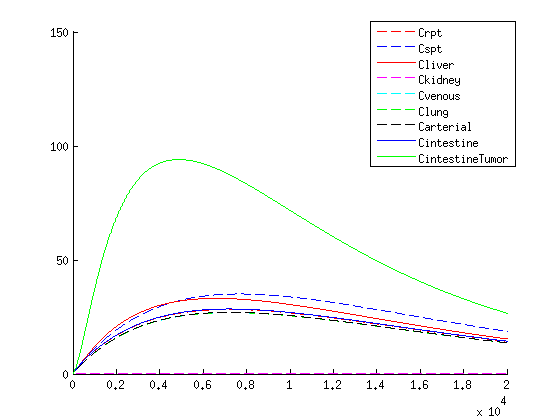

| Conventional treatment |

| ||

| Our VLP treatment |

| ||

|

Conclusion

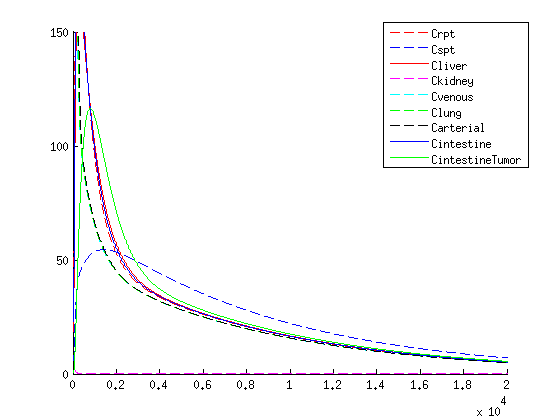

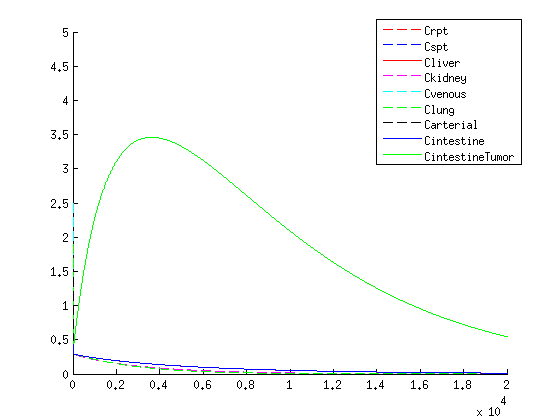

The treatment with the medicine packaged VLPs shows promising results. As seen in figure we get an increase in VLP concentration in the tumor. When the VLPs are breaking apart medicine is released resulting in a 3-4 times higher concentration compared to the healthy tissues, seen in figure 4.

If we compare the results of our treatment with the conventional treatment figure 2 we see a few things:

- The organs get an initional shock of medicine trough the body with the conventional treatment, while with our treatment the medicine is released slowly

- With our treatment we get the same high concentration of medicine in the tumor

- The medicine stays longer in the tumor with our treatment compared to the conventional treatment, this is due to the slow release of medicine.

- Medicine concentration remains low in healthy tissue with our treatment

We find the comparison promising, this shows that our treatment is superior compared to the conventional method according to this method in multiple areas:

- low concentration of medicine in healthy tissue

- Longer exposure of the medicine in the tumor

- No initional dosage shock

Explanation of the parameters

- C[F]: Concentration of the unbound VLPs in a organ

- C[T]: Concentration of all the VLPs in a organ

- C[Med]: Concentration of the medicine in a organ

- V: Volume of the organ

- Q: Flowrate of the organ

- Kel: Rate of decay of the VLPs, releasing the medicine

- K: Rate of elimination of the VLPs, removal of the blood via the urinal track

- RF: Concentration of unbound receptors

- Pb: Partition coefficient in a organ

- ymedvlp: Packeging capacity of the VLP

General mass balance equations for all the VLPs

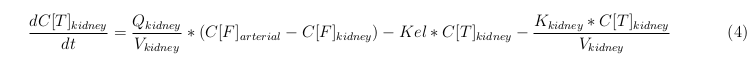

The equations below describe the change in concentration of all the VLPs in the different organs. The mass balances for the different organs consist out of multiple parts. Each organ as at least an flow that describes the concentration of VLPs that come into the organs and a flow that describes the VLP concentration that goes out of the organ. Also each organ has a rate of decay incorporated into the mass balance to describe the falling apart of the VLPs in the different organs. The mass balance of the kidney has also an equation for the removal of the VLPs via the urinal track.

Slowly perfused tissue

Rapid perfused tissue

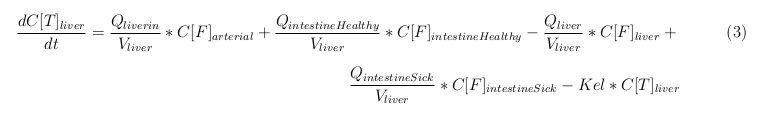

Liver

Kidney

Venous

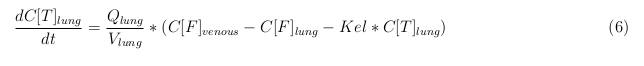

Lung

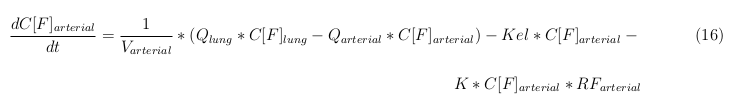

Arterial

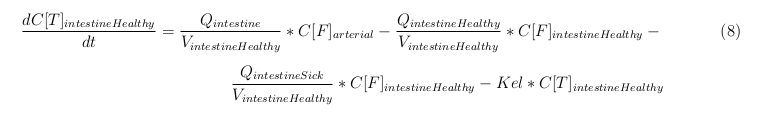

Intestine Healthy

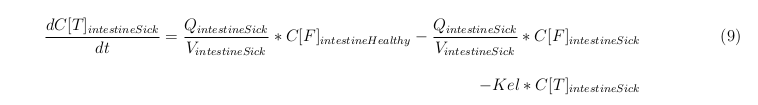

Intestine Sick (Tumor)

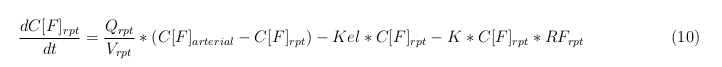

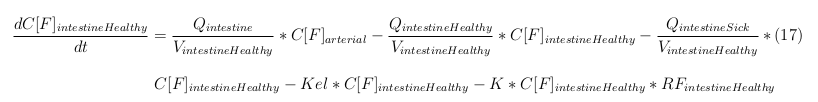

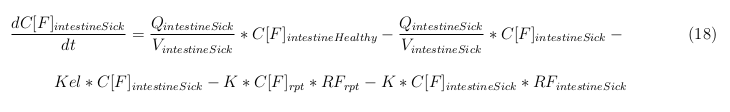

General mass balance equations for the unbound VLPs

Besides needing an equation to describe the change in concentration of all the VLPs, we also need an equation to describe the change in concentration of the unbound VLPs for each organ. The mass balances for the different organs consists out of multiple parts. The mass balances are similar to the mass balance for all the VLPs, with a slight difference, it has a rate of VLP attachment. This rate describes the attachment of the VLPs onto the surface of the cells.

Rapid perfused tissue

Slowly perfused tissue

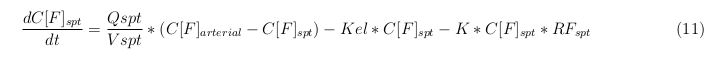

Liver

Kidney

Venous

Lung

Arterial

Intestine Healthy

Intestine Sick (Tumor)

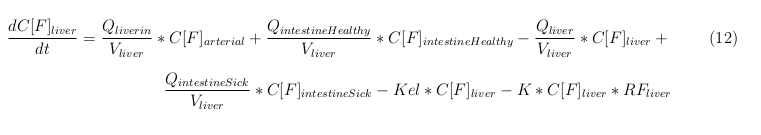

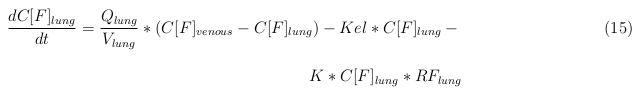

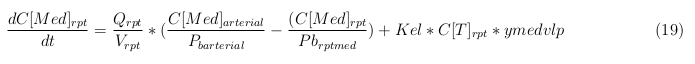

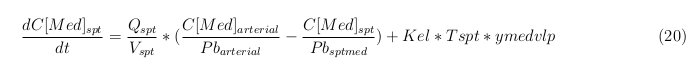

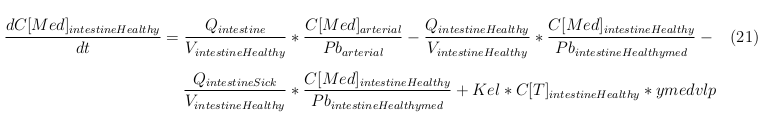

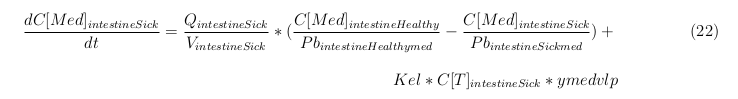

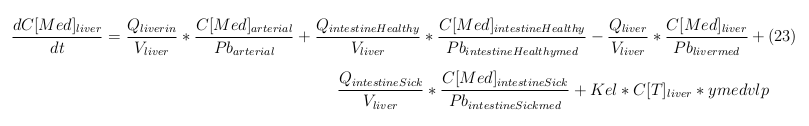

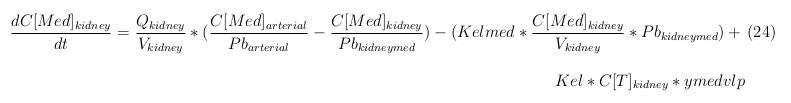

General mass balance equations for the medicine

The last set of mass balances are for the change of concentration of the medicine in the different organs. These equations consists out of multiple parts, similar to the previous set of mass balances. Each organ as at least an flow that describes the concentration of medicine that come into the organs and a flow that describes the medicine concentration that goes out of the organ. Also each organ has a rate of decay incorporated into the mass balance to describe the decay of medicine in the different organs. The mass balance of the kidney has also an equation for the removal of the medicine via the urinal track.

Rapid perfused tissue

Slowly perfused tissue

Intestine Healthy

Intestine Sick (Tumor)

Liver

Kidney

Venous

Lung

Arterial

Remarks

With this model it becomes possible to simulate the VLP and medicine distribution in the human body. However this model, like every model, has it's limitations. Though there are several limitations in the model, it can be used for different scenarios involving the use of VLPs. In this paragraph we'll discus the limitations and it's possibilities of this model and how we can improve this model.

Important parameters

One of the major limitations of every model is the lack of information to determine the parameters. This is the same in this model, shown below is a list of the parameters we've estimated by the little information we've had. If better information becomes available we'll be able to predict a more precise simulation on how the medicine distribute around the body.

- Ratio of receptor concentration between tumor and healthy tissue

- Distribution of receptors on cell surface

- Medicine absorption of tumor / healthy cells

- Stability of the VLP

- Packaging quantity of the VLP

- Binding affinity of the VLP to the receptor

To determine the parameter of the receptor ratio ,receptor distribution and medicine absorption, clinical studies must be done to calculate the parameters. To determine the stability of the VLPs can be done by DLS. The packaging constant can be determined by loading the VLPs and let the particles decay so that you can calculate the medicine-particle ratio. To determine the binding affinity for the receptors, several experiments needs to be done to discover the affinity for the binding. It is also information available on the [http://www.bindingdb.org/bind/index.jsp binding database], however this information is not complete.

Future work

To improve this model several things can be done. First of all, research should be done on several parameters of the model. Specially parameters involving the number of receptors and the breaking down of VLPs. Second looking into other models to further improve the mass balance equations to get a more accurate and faster result. Besides looking for things to build upon, we also want to look at the limitations the model has and how to remove those limitations, creating a more solid model.

Source Code

The model was created within MatLab and the main file can be found here: File:HumanBodyMainB.txt

The function file is located here: File:HumanBodyFB.txt

References

- Jemal A, Bray, F, Center, MM, Ferlay, J, Ward, E, Forman, D; "Global cancer statistics", 2011, CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 61 (2): 69–90

- Cunningham D, Atkin W, Lenz HJ, Lynch HT, Minsky B, Nordlinger B, Starling N; "Colorectal cancer.", 2010, Lancet 375 (9719): 1030–47

- Dr. Mark D. Noble, Chemotherapy-induced Damage to the CNS as a Precursor Cell Disease, University of Rochester

- Benjamin L. Shneider; Sherman, Philip M, Pediatric Gastrointestinal Disease, 2008,Connecticut: PMPH-USA. pp. 751.

- Kaiser CR, et al., Biodistribution studies of protein cage nanoparticles demonstrate broad tissue distribution and rapid clearance in vivo, 2007, Int J Nanomedicine, 2(4):715-33.

- Longley DB, Harkin DP, Johnston PG, 5-fluorouracil: mechanisms of action and clinical strategies", 2007, Nat. Rev. Cancer 3 (5): 330–8

"

"