Team:TU Munich/Modeling/Methods

From 2012.igem.org

(→Derivation) |

|||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

=== Derivation === | === Derivation === | ||

<div> | <div> | ||

| - | Bayes' Rule allow the expression of the probability of A given B in terms of the | + | Bayes' Rule allow the expression of the probability of A given B in terms of the probability of A, B and B given A. |

[[File:TUM12_bayes.png|||center|]] | [[File:TUM12_bayes.png|||center|]] | ||

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

=== What is the problem? === | === What is the problem? === | ||

<div> | <div> | ||

| - | Another problem that was not yet | + | Another problem that was not yet addressed is the question of identifiablity. |

When it is only possible to measure the cumulative amount of the two A and B where the system is governed by the equation | When it is only possible to measure the cumulative amount of the two A and B where the system is governed by the equation | ||

| Line 109: | Line 109: | ||

By replacing the Matlab ode solvers by C++ scripts one can achieve a speedup of the calculations of up to two magnitudes. | By replacing the Matlab ode solvers by C++ scripts one can achieve a speedup of the calculations of up to two magnitudes. | ||

| - | A Wrapper to easily migrate from | + | A Wrapper to easily migrate from Matlab ode code to c++ scripts is easily done with the CVode Wrapper provided by the Systems Biology group from TU Eindhoven [Vanlier, 2010] . |

</div> | </div> | ||

Revision as of 03:46, 27 September 2012

Modeling Methods

Why Mathematical Models?

To be able to predict the behavior of a given biological system, one has to create a mathematical model of the system. The model is usually generated according to the Law of Mass Action and then simplified by assuming certain reactions to be fast. This model then could e.g. facilitate optimizations of bio-synthetic pathways by regulating the relative expression levels of the involved enzymes.

Why are we not necessarily interested in the best fit?

To create a model that produces quantitative predictions, one needs to tune the parameters to fit experimental data. This procedure is called inference and is usually accomplished by computing the least squares approximation of the model to the experimental data with respect to the parameters.

There are several difficulties with this approach: In the case of a non-convex least squares error function several local minima may exist and optimizations algorithms will struggle to find all of them. This means one might not be able to find the best fit or even a biologically reasonable fit.

Another issue with this approach is the fact that it provides no information on the shape of the error function in the neighborhood of the obtained fit. Although it is possible to obtain information about the curvature by computing the hessian of the error function, this can be very computationally intensive if no analytical expression is given and only provides local information.

This poses problems if the error function is very flat. Then in the neighborhood of the set of best fit parameters, a broad range of parameters exist, that produce very similar results. This however drastically reduces the significance of the best fit parameters

What is the benefit of assuming a stochastic distribution of parameters?

Usually biological systems exhibit some sort of stochasticity. If the behavior of a sufficiently large amount of cells is observed, it is justifiable to take only the mean value into consideration and thereby assume a deterministic behavior. On the one hand this means we can describe the system with ordinary and partial differential equations instead of stochastic differential equations, which reduces the computational cost of simulating the system. On the other hand this means that we lose the information we could infer from the variance of our measurements as well as higher order moments.

Assuming that parameter are distributed according to some density allows us, to deduce information from variance of measurements, while still describing the system in a deterministic fashion.

How did Modeling affect our work in the lab?

When planning an experiment, the choice of time intervals and concentrations to use was based on the collaboration between Fabian and the experimenter. Here, previous experiments and literature served as guidance during the decision making.

Bayesian Inference

Derivation

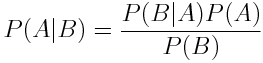

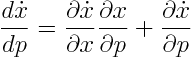

Bayes' Rule allow the expression of the probability of A given B in terms of the probability of A, B and B given A.

We can remove the dependence on the probability of B by applying the law of total probability:

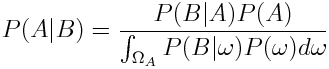

Now as we want to get an expression for the probability of the parameters given our measured data, we plug in parameters for A and data for B we get

As the denominator is constant and only needed to normalize the distribution, we will omit this factor in the future.

Furthermore we will call

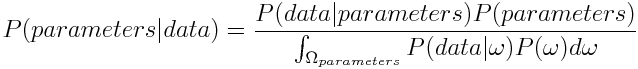

P(parameters|data): posterior

P(data|parameters): likelihood

P(parameters): prior

The likelihood tells us how probable it is the systems will produce the data from the experiments given the selected parameters according to our model.

The prior gives the probability of our parameters, independent of our model or our data. As the name already suggests, the prior gives the option to incorporate prior knowledge about the distribution of the parameters.

Relation to least squares

If we do not know anything about the parameters, e.g. they all have the same probability we can omit the prior. This means that the posterior is equal to the likelihood.

Now if the likelihood is a Gaussian distribution, maximizing the logarithm of the likelihood, as function of the parameters, is the same as finding the least squares approximation.

Monte Carlo Methods

Usually it is not possible to give any closed expression for the posterior distribution. When working with high dimensional posteriors where the location of the support of the distribution is not clear, interpolating the posterior will be very hard. Hence alternative methods are necessary to get an idea of the shape of the posterior distribution. The book by David MacKay http://www.inference.phy.cam.ac.uk/mackay/itila/book.html MacKay, 2003 gives an good overview of available algorithms.

The general idea of Monte Carlo methods is to draw random samples and accept or reject them, in such a manner that the samples will eventually be drawn according to a certain, evaluable distribution.

We will use the Metropolis Hastings algorithm as it is easy to implement and sufficiently fast to sample our posteriors.

Identifiability

What is the problem?

Another problem that was not yet addressed is the question of identifiablity. When it is only possible to measure the cumulative amount of the two A and B where the system is governed by the equation

the measurement will, apart from errors always produce the same value. This means that it is impossible to infer the value of the measurement b. As all values of will b produce an equivalent fit, all results of optimization routines will be meaningless.

In actual inference task we will most likely not deal with such extreme non-identifiabilities but it could happen that for example only the ratio between two parameters is identifiable but not the individual values. Such behavior can be visible in marginal joint distributions generated by Markov Methods, but one will have a hard time spotting more complex non-identifiabilities from joint distributions.

Profile Likelihood

In that cases one normally looks at the profile likelihood of the distribution. The profile likelihood is generated by maximizing the likelihood/posterior for a set fixed value of one parameter with respect to the other remaining parameters. When this profile likelihood for one parameter is flat, all changes to this parameter can be balanced by a change of the other parameters and the examined parameters is not identifiablehttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22355081 Vanlier et al., 2012b.

CVode Wrapper

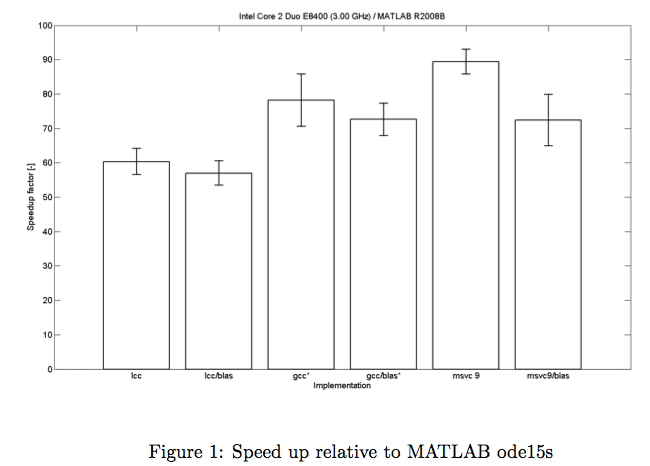

When every evaluation of the posterior requires solving a set of ordinary differential equation, generating several thousand samples can be quite time consuming. Hence speeding up the solving routine is desirable.

By replacing the Matlab ode solvers by C++ scripts one can achieve a speedup of the calculations of up to two magnitudes.

A Wrapper to easily migrate from Matlab ode code to c++ scripts is easily done with the CVode Wrapper provided by the Systems Biology group from TU Eindhoven [Vanlier, 2010] .

Sensitivity Analysis

To assess in what magnitude changes in parameters are reflected in the simulation, one can perform sensitivity analysis. Absolute sensitivity is obtained by computing the total differential of the right hand side of the differential equation with respect to each parameter.

The solution to this matrix valued differential equation gives us the absolute sensitivity for every species with respect to every parameter. Multiplying every entry of this matrix with the value of the species and divide it by the value of the parameter for every point in time gives the relative sensitivity.

Vision

Bayesian Inference fits into the setting of BioBricks very well: Priors are small parts that are added to your simulation, and either you improve them by performing inference yourself and adding the resulting marginal distribution of the parameter as new, improved prior or you only use them to simulate the system.

As the number of teams increases every year and more and more data is generated over the years, the incremental nature of the method will great improvements to the quality of models.

The repertoire of methods displayed here represents only a small fraction of the methods available via Bayesian Inference. Bayesian Inference also offer powerful tools to

- Compare the performance of different models http://projecteuclid.org/euclid.aos/1176344136 Schwarz, 1978

- Facilitate well-founded experimental design http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22368245 Vanlier et al., 2012a

Reference

- http://www.inference.phy.cam.ac.uk/mackay/itila/book.html MacKay, 2003 MacKay, D. J. C. (2003). Information Theory, Inference, and Learning Algorithms. Cambridge University Press.

- http://projecteuclid.org/euclid.aos/1176344136 Schwarz, 1978 Schwarz, G. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. Annals of Statistics, 6(2):461–464.

- [Vanlier, 2010] Vanlier, J. (2010). Installation and usage instructions for the cvode wrapper.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22368245 Vanlier et al., 2012a Vanlier, J., Tiemann, C. A., Hilbers, P. A. J., and van Riel, N. A. W. (2012a). A bayesian approach to targeted experiment design. Bioinformatics, 28(8):1136–42.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22355081 Vanlier et al., 2012b Vanlier, J., Tiemann, C. A., Hilbers, P. A. J., and van Riel, N. A. W. (2012b). An integrated strategy for prediction uncertainty analysis. Bioinformatics, 28(8):1130–5.

"

"