Team:Stanford-Brown/VenusLife/Atmosphere

From 2012.igem.org

(→Venusian Atmosphere) |

|||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

{{:Team:Stanford-Brown/Templates/Content}} | {{:Team:Stanford-Brown/Templates/Content}} | ||

== '''Venusian Atmosphere''' == | == '''Venusian Atmosphere''' == | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Atmosphere1.jpg|left|300px400px|frameless]] | ||

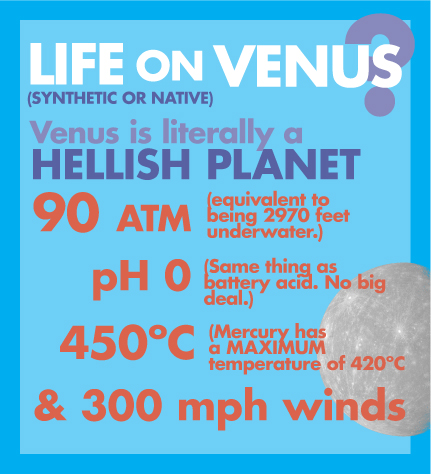

The surface of Venus constitutes perhaps the most hellish and biologically inhospitable places, boasting a pH of 0, blistering winds that can melt lead, pressures of 60 atm, and temperatures at a balmy 735 K (1). Because of these conditions, Venus is normally written off immediately in discussion of life outside of Earth (2). Indeed, planets such as Mars, or the icy Moons Europa and Titan, usually get all of the attention in our solar system (2). But do we really have a concrete understanding of what “life” is? | The surface of Venus constitutes perhaps the most hellish and biologically inhospitable places, boasting a pH of 0, blistering winds that can melt lead, pressures of 60 atm, and temperatures at a balmy 735 K (1). Because of these conditions, Venus is normally written off immediately in discussion of life outside of Earth (2). Indeed, planets such as Mars, or the icy Moons Europa and Titan, usually get all of the attention in our solar system (2). But do we really have a concrete understanding of what “life” is? | ||

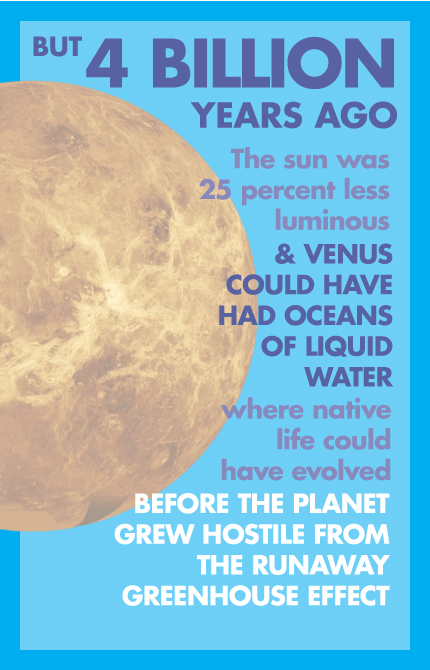

It may come as a surprise that Venus was not always so inhospitable. Many planetary scientists argue that Venus at one point had oceans. There is a small, dissenting view that argues otherwise, but most climate models of the planet begin with oceans (3). Whether Venus had oceans because it was already present in the rocks, or because it came with comets, it “should not have escaped whatever it was that gave Earth its water” (1). | It may come as a surprise that Venus was not always so inhospitable. Many planetary scientists argue that Venus at one point had oceans. There is a small, dissenting view that argues otherwise, but most climate models of the planet begin with oceans (3). Whether Venus had oceans because it was already present in the rocks, or because it came with comets, it “should not have escaped whatever it was that gave Earth its water” (1). | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

So, the proposed geological history of Venus goes something like this: | So, the proposed geological history of Venus goes something like this: | ||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

What if life once existed in those oceans, when Venus was more Earth-like? Could it have evolved to live anywhere on the planet as it exists now? | What if life once existed in those oceans, when Venus was more Earth-like? Could it have evolved to live anywhere on the planet as it exists now? | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

[[File:Atmosphere3.jpg|left|300px400px|frameless]] | [[File:Atmosphere3.jpg|left|300px400px|frameless]] | ||

| + | |||

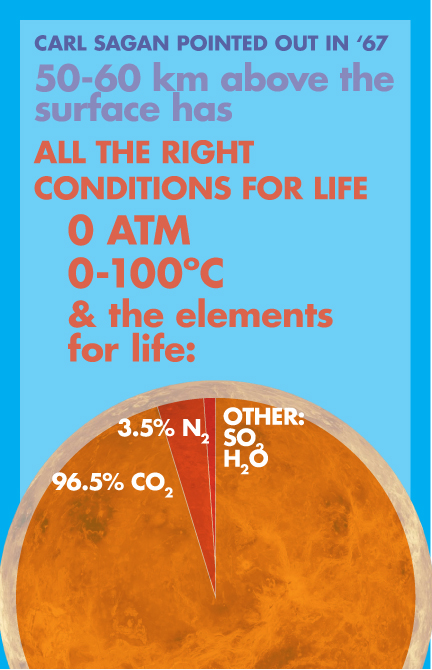

| + | Interestingly enough, there is an area in the clouds of Venus, 50-60 km above the surface of the planet, which maintains very Earth-like environmental conditions. The temperature here ranges from about 80 degrees celsius to about -10 degrees celsius (4). The atmospheric pressure is around 1 atm, the same as that of Earth’s surface (4). The atmosphere itself is around 96% carbon dioxide, 3% nitrogen, and 0.003% water vapor (5). The clouds themselves are predominantly made up of sulfuric acid (4). Even sunlight is in ample availability (4). Thus, the necessary environmental conditions and compounds are present for life as we know it on Earth. | ||

The cloud layer of Venus did not escape the imagination of Carl Sagan as a place for life. In 1967, Sagan hypothesized that an organism, something along the lines of an isopynic organism resembling a float bladder, could survive here (6). One might argue that the clouds would be a highly unstable environment for life. However, some models indicate that cloud particles last for several months on Venus, much longer than those on Earth (2). | The cloud layer of Venus did not escape the imagination of Carl Sagan as a place for life. In 1967, Sagan hypothesized that an organism, something along the lines of an isopynic organism resembling a float bladder, could survive here (6). One might argue that the clouds would be a highly unstable environment for life. However, some models indicate that cloud particles last for several months on Venus, much longer than those on Earth (2). | ||

Revision as of 02:40, 4 October 2012

Venusian Atmosphere

The surface of Venus constitutes perhaps the most hellish and biologically inhospitable places, boasting a pH of 0, blistering winds that can melt lead, pressures of 60 atm, and temperatures at a balmy 735 K (1). Because of these conditions, Venus is normally written off immediately in discussion of life outside of Earth (2). Indeed, planets such as Mars, or the icy Moons Europa and Titan, usually get all of the attention in our solar system (2). But do we really have a concrete understanding of what “life” is?

It may come as a surprise that Venus was not always so inhospitable. Many planetary scientists argue that Venus at one point had oceans. There is a small, dissenting view that argues otherwise, but most climate models of the planet begin with oceans (3). Whether Venus had oceans because it was already present in the rocks, or because it came with comets, it “should not have escaped whatever it was that gave Earth its water” (1).

So, the proposed geological history of Venus goes something like this:

- Four billion years ago, when the sun was 25% less luminous than it was today, Venus had oceans and was perhaps a little bit more Earth-like. (4)

- The sun’s luminosity gradually increased, creating a runaway greenhouse effect that trapped the planet in a devastating cycle of heating (4).

- As the temperature of Venus kept rising, the oceans began to evaporate. Water vapor is a greenhouse gas and thus trapped infrared radiation inside the atmosphere, further heating the planet (4).

- The feedback loop at some point boiled the oceans dry, and with a last gasp of greenhouse gas, the carbonate rocks on the surface decomposed and spilled carbon dioxide into the atmosphere (4).

- It is highly uncertain how long these oceans might have lasted on the planet, but 600 million years is a number that has been produced from models (1).

What if life once existed in those oceans, when Venus was more Earth-like? Could it have evolved to live anywhere on the planet as it exists now?

Interestingly enough, there is an area in the clouds of Venus, 50-60 km above the surface of the planet, which maintains very Earth-like environmental conditions. The temperature here ranges from about 80 degrees celsius to about -10 degrees celsius (4). The atmospheric pressure is around 1 atm, the same as that of Earth’s surface (4). The atmosphere itself is around 96% carbon dioxide, 3% nitrogen, and 0.003% water vapor (5). The clouds themselves are predominantly made up of sulfuric acid (4). Even sunlight is in ample availability (4). Thus, the necessary environmental conditions and compounds are present for life as we know it on Earth.

The cloud layer of Venus did not escape the imagination of Carl Sagan as a place for life. In 1967, Sagan hypothesized that an organism, something along the lines of an isopynic organism resembling a float bladder, could survive here (6). One might argue that the clouds would be a highly unstable environment for life. However, some models indicate that cloud particles last for several months on Venus, much longer than those on Earth (2).

Our team could not travel to Venus, nor convince NASA to send an un-manned expedition to the planet in one summer, but Synthetic Biology can certainly answer some of our questions about life in the clouds.

References

1. Grinspoon, David. "Was Venus Alive? 'The Signs Are Probably There'" Interview by Henry Bortman. Space.com. Astrobiology Magazine, 26 Aug. 2004. Web. 2 Sept. 2012. <http://www.space.com/283-venus-alive-signs.html>.

2. Grinspoon, David Harry. Venus Revealed: A New Look below the Clouds of Our Mysterious Twin Planet. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Pub., 1997.

3. Grinspoon, David. "Venus Life Project and its Implications." Interview by Bryce Bajar, Chris Jackson, Ben Geilich, Jason Hu, Debha Amatya, and Lynn Rothschild.

4. Landis, Geoffrey A. “Astrobiology: The Case for Venus.” National Aeronautics and Space Administration. 2003.

5. Astronomy Today. “Venus, the hottest planet in the solar system.” www.astronomytoday.com/astronomy/venus.html

6. Morowitz, Harold, and Carl Sagan. "Life in the Clouds of Venus?" Nature 215.5107 (1967): 1259-260.

"

"