Team:TU-Eindhoven/LEC/LabTheory

From 2012.igem.org

Nickveeken (Talk | contribs) |

|||

| (37 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{:Team:TU-Eindhoven/Templates/header}} | {{:Team:TU-Eindhoven/Templates/header}} | ||

| - | {{:Team:TU-Eindhoven/Templates/head|image=https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2012/ | + | {{:Team:TU-Eindhoven/Templates/head|image=https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2012/c/cb/Labapproach.jpg}} |

| + | <h3>Design challenge</h3> | ||

| - | + | <p>The aim of this project is to design and produce a new multi-colored display in which genetically engineered cells function as pixels analogous to a conventional display. In the lab we will create cells that emit light in response to an electric stimulus. This can be achieved by <span class= "lightblue">genetic modification of yeast cells</span>, through the introduction of fluorescent calcium sensors and utilizing the already present calcium channels. Already anticipating on the probably slow response time of our 'pixel' we also intend to over express the calcium channels together with the expression of the GECO proteins as a means to enhance the calcium flux. On top of our great endeavor an other innovative aspect is the fact that our system responds to <span class= "lightblue">exogeneous stimuli</span> instead of the more traditional systems which respond to intracellular processes.</p> | |

| - | <p> | + | |

| - | < | + | <p>The plasma membrane of the brewer's yeast <i>Saccharomyces cerevisiae</i> contains the <span class= "lightblue">CCH1-MID1 channel</span> that is homologous to mammalian voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs). It is hypothesized that upon depolarization of the plasma membrane <span class= "lightblue">calcium ions selectively enter the cytoplasm</span> through these channels<html><a href="#ref_Iida"name="text_Iida"><sup>[1]</sup></a></html>. Light will be emitted by fluorescence of the <span class= "lightblue">GECO protein</span><html><a href="#ref_zhao"name="text_zhao"><sup>[2]</sup></a></html>, a calcium dependent fluorescent protein that is expressed from a genetically engineered plasmid. When this calcium sensor is exposed to an elevated intracellular calcium concentration its fluorescence will increase significantly; consequently when the calcium concentration drops its fluorescence will diminish. The calcium can enter the cell's cytoplasm upon electrical stimulation of the calcium channel, after which the GECO protein will start to fluoresce. Finally the excess of calcium will be removed by active transport within the cell to restore it's <span class= "lightblue">homeostatic level</span>, and the amount of fluorescence will decrease.</p> |

| - | <p> | + | <p>Challenges in the laboratory can be found in creating yeast cells with the GECO protein as well as a sufficient amount of calcium channels which consist of two separate proteins. The important design choices regarding the biological work are further motivated in the text below.</p> |

| - | <h3> | + | <div class="vectorImage">[[File:Plasmids.jpg|center|link=]]</div> |

| - | + | <p>Fig. 1 Yeast cell with the needed plasmids</p> | |

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | <h3>Chassis</h3> | ||

| + | <p>Before this light emitting cell display project could start, it was necessary to decide on a suitable chassis. Candidates were E. coli and S. cerevisiae. Both are common model organisms that can be used for protein expression and are cheap to culture. To reach the goal of this project expression of <span class= "lightblue">voltage-gated calcium channel</span> is needed, which luckily is already the case for S. cerevisiae. Therefore, it was decided to use S. cerevisiae as our chassis throughout the project. More specifically, we used the <span class= "lightblue">INVSc1 yeast strain</span> which is compatible with the choice of vectors. Additional benefits when using yeast is that there are still only a <span class= "lightblue">few BioBricks<sup>TM</sup></span> available, which creates a greater opportunity to contribute to the Registry, but also the drawback of having less BioBricks<sup>TM</sup> available to ourselves. Another benefit is that, at the moment, the manipulation of yeast is <span class= "lightblue">less standardized</span> than it is for E. coli, which ultimately means that our research is <span class= "lightblue">more innovative</span>.</p> | ||

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | <h3>Plasmids and transformations</h3> | ||

| - | < | + | <p>Since we choose yeast as the chassis we preferred to clone all required genes into <span class= "lightblue">shuttle vectors</span>. A shuttle vector is a special type of vector that can be propagated both in yeast and in bacteria. For our purposes we choose to use <span class= "lightblue">high copy-number vector</span> in order to achieve high concentration of GECO protein.</p> |

| - | < | + | |

| - | < | + | <p>The proteins CCH1 and MID1 together constitute a high-affinity Ca<sup>2+</sup>-channel. Both proteins are brought to expression on a <span class= "lightblue">low copy-number shuttle vector</span>. We are thankful to <span class= "lightblue">Hidetoshi Iida and Kazuko Iida</span> for their donation of the shuttle vectors pBCT-CCH1H and YCpT-MID1 which they constructed in earlier research.</p> |

| - | <p> | + | <p>The GECO proteins that were engineered in the group of <span class= "lightblue">Robert E. Campbell</span> (Zhao et al., 2011<sup>[2]</sup>) are available from Addgene.org, a non-profit plasmid sharing service. Via PCR we cloned the GECOs from the shipping plasmid into a pYES3 shuttle vector acquired from Invitrogen (Fig. 1).</p> |

| - | <p> | + | <p>Transformation of S. cerevisiae cells can be done with a heat shock. To obtain a cell containing all the 3 different plasmids, <span class= "lightblue">3 consecutive transformations</span> are needed. Since we have 3 different GECOs, in the end we will have <span class= "lightblue">3 different variants</span>, all containing the CCH1-MID1 calcium channel but each with a different color of GECO.</p> |

| - | <p>The | + | <p>The order in which plasmids are introduced can be varied. The route requiring the least transformations introduces first the CCH1 and MID1 proteins and finally the 3 different GECOs. Doing so, one can obtain all 3 variants by using 5 transformations, if the GECOs are first introduced the CCH1 and MID1 proteins, they need to be introduced separate to every GECO strain; this results in <span class= "lightblue">9 transformations in total</span>. Even though the second approach is more cumbersome, trying other routes in parallel provides a backup in case certain transformations fail.</p> |

| - | <p> | + | <p>Selection of successful transformants is done by making use of <span class= "lightblue">auxotrophic markers</span>, a different one for each vector. The INVSc1 strain we use for transformations is auxotrophic in <span class= "lightblue">histidine, leucine, tryptophan and uracil</span>. These usually have to be added to the medium for the yeast to survive. The uptake of a vector however, will restore the ability of the cell to synthesize the missing amino acid or nucleic acid, and therefore it can survive in a selective medium.</p> |

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | <h3>Compatibility of yeast and device</h3> | ||

| - | <p>The | + | <p>The genetically modified S. cerevisiae cells will be put to the test in our <span class= "lightblue">home-made</span> [[Team:TU-Eindhoven/LEC/Device|device]], designed for providing electrical stimuli to the yeast cells. These tests are done in a single bath filled with SC medium containing nutrients for our genetically modified yeast and additional free Ca<sup>2+</sup> ions. After <span class= "lightblue">electrical stimulation</span> of yeast at different positions in the device, optical signals will be expected to be visible to the naked eye. In a more <span class= "lightblue">sensitive analysis</span>, isolated protein will be characterized on a <span class="lightblue">spectrophotometer</span>.</p> |

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | <h3>GECOs</h3> | ||

| - | <p> | + | <p>Real-time imaging of biochemical events inside living cells is important for understanding the molecular basis of physiological processes and diseases<html><a href="#ref_merkx" name="text_merkx"><sup>[3]</sup></a></html>. Genetically encoded sensors based on fluorescent proteins (FPs) are frequently used for <span class= "lightblue">molecular recognition</span>. In this iGEM project we use fluorescent proteins to provide the light in our display. More specifically we make use the so called GECOs.</p> |

| - | |||

| - | <p> | + | [[File:Making_GECO.png|600px]] |

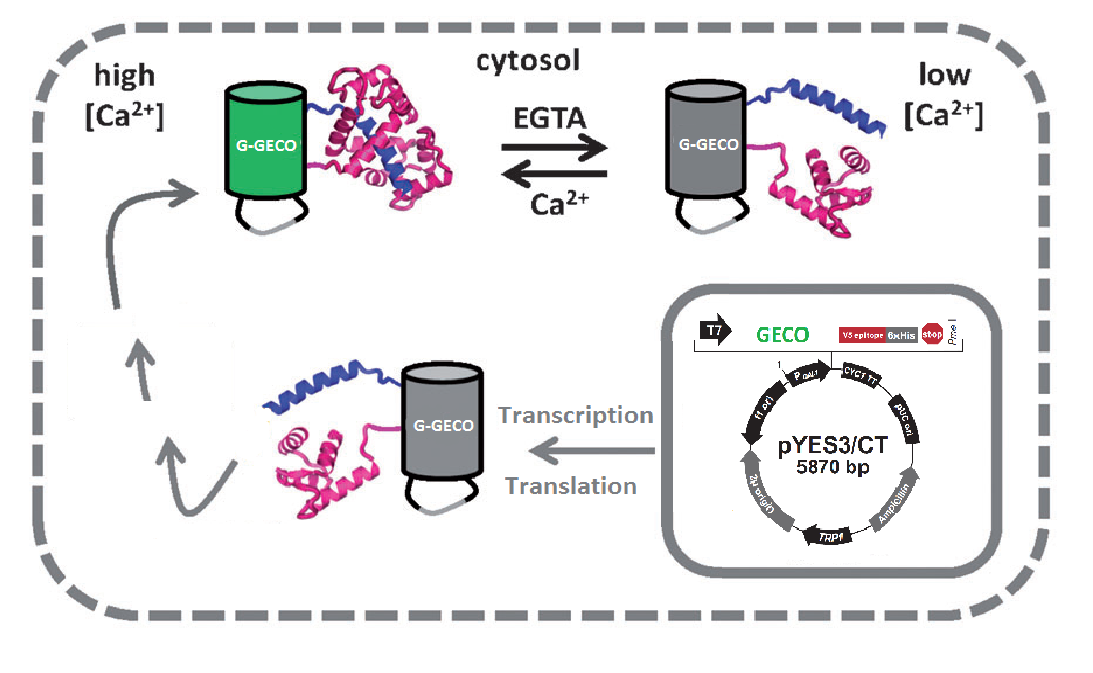

| - | + | <p>Fig. 2 Cartoon representation of the calcium dependence</p> | |

| - | + | ||

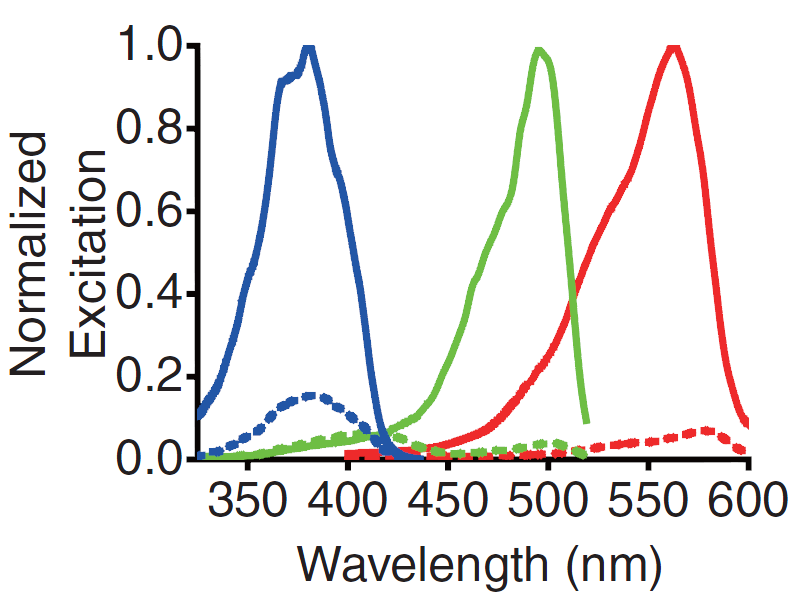

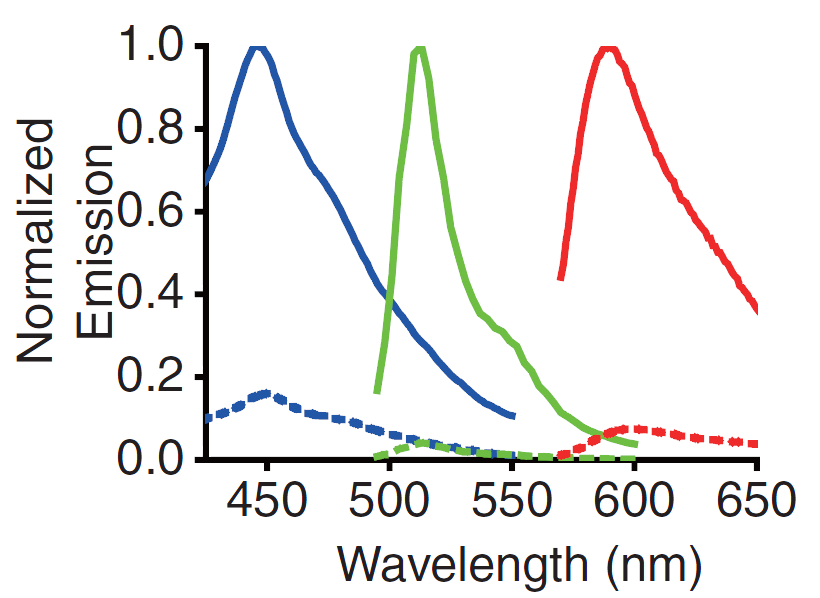

| - | <p> | + | <p>A GECO is a protein which is fluorescent in the presence of Ca<sup>2+</sup><html><a href="#ref_zhao" name="text_zhao"><sup>[2]</sup></a></html> (Fig. 2). There are two important classes of <span class= "lightblue">genetically encoded Ca<sup>2+</sup> indicators</span>. One is called the Forster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)-based cameleon type<html><a href="#ref_miyawaki" name="text_miyawaki"><sup>[4]</sup></a></html> and the other one is called the single Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) type<html><a href="#ref_nakai" name="text_nakai"><sup>[5]</sup></a></html>. The GECO protein belongs to the single GFP type. Research has shown that Ca<sup>2+</sup> indicators targeted to the E. coli periplasm can be shifted toward the Ca<sup>2+</sup>-free or Ca<sup>2+</sup>-bound states by <span class= "lightblue">manipulation of the intracellular Ca<sup>2+</sup> concentration</span><html><a href="#ref_zhao" name="text_zhao"><sup>[2]</sup></a></html>. Robert E. Campbell et al. named these Ca<sup>2+</sup> calcium sensors GECOs. <span class= "lightblue">R-GECO, G-GECO and B-GECO</span> emit red, green and blue light respectively, each with their own distinct excitation and emission spectrum (Fig. 3).</p> |

| - | [ | + | |

| - | + | [[File:Excitation spectra GECO.png|300px]] [[File:Emission spectra GECO.png|300px]] | |

| + | <p>Fig. 3 Excitation and emission spectra of the GECO's</p> | ||

<h3>References</h3> | <h3>References</h3> | ||

| Line 44: | Line 50: | ||

<html> | <html> | ||

<ul> | <ul> | ||

| - | <li><a href="#text_Iida" name="ref_Iida">[1]</a> | + | <li><a href="#text_Iida" name="ref_Iida">[1]</a> K. Iida, et al., Essential, completely conserved glycine residue in the domain III S2S3 linker of voltage-gated calcium channel α1 subunits in yeast and mammals, Journal of Biological Chemistry 282: 25659-25667, (2007)</a></li> |

| - | <li><a href="#text_zhao" name="ref_zhao">[2]</a> | + | <li><a href="#text_zhao" name="ref_zhao">[2]</a> Y. Zhao, et al., An expanded palette of genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators, Science 333: 1888-1891, (2011)</a></li> |

| - | <li><a href="#text_merkx" name="ref_merkx">[3]</a > | + | <li><a href="#text_merkx" name="ref_merkx">[3]</a > L. Lindenburg and M. Merkx, Colorful calcium sensors, (2012)</a></li> |

| - | <li><a href="#text_miyawaki" name="ref_miyawaki">[4]</a> A. Miyawaki et al., Nature 338, 1997</a></li> | + | <li><a href="#text_miyawaki" name="ref_miyawaki">[4]</a> A. Miyawaki, et al., Nature 338, (1997)</a></li> |

| - | <li><a href="#text_nakai" name="ref_nakai">[5]</a> J. Nakai, M. Ohkura, K. Imoto, Nat. Biotechnol. (2001)</a></li> | + | <li><a href="#text_nakai" name="ref_nakai">[5]</a> J. Nakai, M. Ohkura, K. Imoto, Nat. Biotechnol., (2001)</a></li> |

</ul> | </ul> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

{{:Team:TU-Eindhoven/Templates/footer}} | {{:Team:TU-Eindhoven/Templates/footer}} | ||

Latest revision as of 01:24, 27 September 2012

Design challenge

The aim of this project is to design and produce a new multi-colored display in which genetically engineered cells function as pixels analogous to a conventional display. In the lab we will create cells that emit light in response to an electric stimulus. This can be achieved by genetic modification of yeast cells, through the introduction of fluorescent calcium sensors and utilizing the already present calcium channels. Already anticipating on the probably slow response time of our 'pixel' we also intend to over express the calcium channels together with the expression of the GECO proteins as a means to enhance the calcium flux. On top of our great endeavor an other innovative aspect is the fact that our system responds to exogeneous stimuli instead of the more traditional systems which respond to intracellular processes.

The plasma membrane of the brewer's yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains the CCH1-MID1 channel that is homologous to mammalian voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs). It is hypothesized that upon depolarization of the plasma membrane calcium ions selectively enter the cytoplasm through these channels[1]. Light will be emitted by fluorescence of the GECO protein[2], a calcium dependent fluorescent protein that is expressed from a genetically engineered plasmid. When this calcium sensor is exposed to an elevated intracellular calcium concentration its fluorescence will increase significantly; consequently when the calcium concentration drops its fluorescence will diminish. The calcium can enter the cell's cytoplasm upon electrical stimulation of the calcium channel, after which the GECO protein will start to fluoresce. Finally the excess of calcium will be removed by active transport within the cell to restore it's homeostatic level, and the amount of fluorescence will decrease.

Challenges in the laboratory can be found in creating yeast cells with the GECO protein as well as a sufficient amount of calcium channels which consist of two separate proteins. The important design choices regarding the biological work are further motivated in the text below.

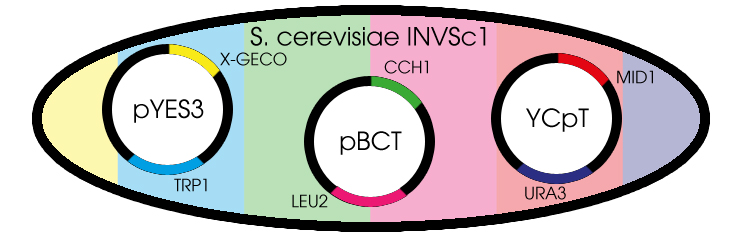

Fig. 1 Yeast cell with the needed plasmids

Chassis

Before this light emitting cell display project could start, it was necessary to decide on a suitable chassis. Candidates were E. coli and S. cerevisiae. Both are common model organisms that can be used for protein expression and are cheap to culture. To reach the goal of this project expression of voltage-gated calcium channel is needed, which luckily is already the case for S. cerevisiae. Therefore, it was decided to use S. cerevisiae as our chassis throughout the project. More specifically, we used the INVSc1 yeast strain which is compatible with the choice of vectors. Additional benefits when using yeast is that there are still only a few BioBricksTM available, which creates a greater opportunity to contribute to the Registry, but also the drawback of having less BioBricksTM available to ourselves. Another benefit is that, at the moment, the manipulation of yeast is less standardized than it is for E. coli, which ultimately means that our research is more innovative.

Plasmids and transformations

Since we choose yeast as the chassis we preferred to clone all required genes into shuttle vectors. A shuttle vector is a special type of vector that can be propagated both in yeast and in bacteria. For our purposes we choose to use high copy-number vector in order to achieve high concentration of GECO protein.

The proteins CCH1 and MID1 together constitute a high-affinity Ca2+-channel. Both proteins are brought to expression on a low copy-number shuttle vector. We are thankful to Hidetoshi Iida and Kazuko Iida for their donation of the shuttle vectors pBCT-CCH1H and YCpT-MID1 which they constructed in earlier research.

The GECO proteins that were engineered in the group of Robert E. Campbell (Zhao et al., 2011[2]) are available from Addgene.org, a non-profit plasmid sharing service. Via PCR we cloned the GECOs from the shipping plasmid into a pYES3 shuttle vector acquired from Invitrogen (Fig. 1).

Transformation of S. cerevisiae cells can be done with a heat shock. To obtain a cell containing all the 3 different plasmids, 3 consecutive transformations are needed. Since we have 3 different GECOs, in the end we will have 3 different variants, all containing the CCH1-MID1 calcium channel but each with a different color of GECO.

The order in which plasmids are introduced can be varied. The route requiring the least transformations introduces first the CCH1 and MID1 proteins and finally the 3 different GECOs. Doing so, one can obtain all 3 variants by using 5 transformations, if the GECOs are first introduced the CCH1 and MID1 proteins, they need to be introduced separate to every GECO strain; this results in 9 transformations in total. Even though the second approach is more cumbersome, trying other routes in parallel provides a backup in case certain transformations fail.

Selection of successful transformants is done by making use of auxotrophic markers, a different one for each vector. The INVSc1 strain we use for transformations is auxotrophic in histidine, leucine, tryptophan and uracil. These usually have to be added to the medium for the yeast to survive. The uptake of a vector however, will restore the ability of the cell to synthesize the missing amino acid or nucleic acid, and therefore it can survive in a selective medium.

Compatibility of yeast and device

The genetically modified S. cerevisiae cells will be put to the test in our home-made device, designed for providing electrical stimuli to the yeast cells. These tests are done in a single bath filled with SC medium containing nutrients for our genetically modified yeast and additional free Ca2+ ions. After electrical stimulation of yeast at different positions in the device, optical signals will be expected to be visible to the naked eye. In a more sensitive analysis, isolated protein will be characterized on a spectrophotometer.

GECOs

Real-time imaging of biochemical events inside living cells is important for understanding the molecular basis of physiological processes and diseases[3]. Genetically encoded sensors based on fluorescent proteins (FPs) are frequently used for molecular recognition. In this iGEM project we use fluorescent proteins to provide the light in our display. More specifically we make use the so called GECOs.

Fig. 2 Cartoon representation of the calcium dependence

A GECO is a protein which is fluorescent in the presence of Ca2+[2] (Fig. 2). There are two important classes of genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators. One is called the Forster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)-based cameleon type[4] and the other one is called the single Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) type[5]. The GECO protein belongs to the single GFP type. Research has shown that Ca2+ indicators targeted to the E. coli periplasm can be shifted toward the Ca2+-free or Ca2+-bound states by manipulation of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration[2]. Robert E. Campbell et al. named these Ca2+ calcium sensors GECOs. R-GECO, G-GECO and B-GECO emit red, green and blue light respectively, each with their own distinct excitation and emission spectrum (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Excitation and emission spectra of the GECO's

References

- [1] K. Iida, et al., Essential, completely conserved glycine residue in the domain III S2S3 linker of voltage-gated calcium channel α1 subunits in yeast and mammals, Journal of Biological Chemistry 282: 25659-25667, (2007)

- [2] Y. Zhao, et al., An expanded palette of genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators, Science 333: 1888-1891, (2011)

- [3] L. Lindenburg and M. Merkx, Colorful calcium sensors, (2012)

- [4] A. Miyawaki, et al., Nature 338, (1997)

- [5] J. Nakai, M. Ohkura, K. Imoto, Nat. Biotechnol., (2001)

"

"