Team:Wageningen UR/Coil system

From 2012.igem.org

(→"leucine zipper" coils) |

Lisamsonne (Talk | contribs) (→GFP with the E-coil) |

||

| (122 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Template: WUR}} | {{Template: WUR}} | ||

| - | + | <html><script>document.getElementById("header_slider").style.backgroundImage = "url(https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2012/6/60/HeaderProject.jpg)";</script></html> | |

| - | = The Plug and Apply (PnA) system | + | = The Plug 'n Apply system (PnA system)= |

| + | A big challenge of our project is the attachment of ligands and functional proteins on either the outside or inside of a virus-like particle ([[Team:Wageningen_UR/VLPs|VLP]]). We decided to use a noncovalent anchor-like system, which consists of two different coiled-coil proteins. We called it the Plug-and-Apply-system (PnA-system). In figure 1 is shown the actual connection of a ligand (yellow color) via the PnA-system (shown in red and green color) to a VLP (light blue colour). | ||

| + | <br><br> | ||

| + | [[File:VLP click.jpg|center|thumb|600px|''Figure 1: The Plug-and-Apply-system. The VLP (blue) is fused to the E-coil (red) and the ligand (yellow) will be fused to the K-coil (green) as described in the follwing texts'']] | ||

| + | <br><br> | ||

== E- and K-coil == | == E- and K-coil == | ||

| - | [[File:GNC4_homodimer.jpg|thumb|100px|''Figure | + | [[File:GNC4_homodimer.jpg|thumb|100px|''Figure 2: homodimeric GCN4 leucine zipper'']] |

<p align="justify"> | <p align="justify"> | ||

| - | + | For various experiments the E-/K-coil combination IAAL E3 and IAAL K3 reported by Litowksi et al. in 2002 was used. | |

| - | + | <br /> | |

| - | α-helical coiled-coils represent | + | <br /> |

| - | + | α-helical coiled-coils represent a widely abundant but simple oligomerization motif in proteins. They have an enormous diversity of functions in nature ranging from motor proteins to transcription factors and chaperones [1]. Coiled-coils are comprised of one single secondary protein structure: the α-helix. Their quaternary structure is stable and does not unfold in aqueous solution at a neutral pH unlike other peptide α-helices. One of the striking structural features of the coiled coils is their build-up of two to five α-helices. These helices contain a heptad repeat of mainly apolar amino acids which is denoted as '''(abcdefg)^n''' in literature. The letters '''a''' and '''d''' are usually amino acids with a highly hydrophobic side chain. The side chains are packed against each other forming a hydrophobic core which allows the formation of a supercoil. Whereas the letter '''n''' is representing the number of helices in the final coil. The helices can be identical or even different in sequence and may be aligned in a parallel/antiparallel way. The amino acids of the letters '''e''' and '''g''' have typically charged residues to allow electrostatic interactions with other peptides (most importantly other coils)[2]. The process of dimerization is largely dependent on the peptide sequence and can be homodimeric (Figure 2.) or heterodimeric (e.g. E- and K-coil). In our project we are utilizing heterodimeric coiled-coils to noncovalently attach proteins. This system is advantageous because of the high stability and specificity. The use of heterodimeric coils additionally prevents the self-dimerization of either the virus capsid monomer or the protein (or ligand) of choice. | |

| - | + | <br /> | |

| - | [[File:Coiled-coils interactions.JPG|500px|center|thumb|''Figure | + | <br /> |

| + | [[File:Coiled-coils interactions.JPG|500px|center|thumb|''Figure 3: cross-section view of a E-/ K-coil heterodimer''</p>]]<!-- --><br /> | ||

<p align="justify"> | <p align="justify"> | ||

| - | In figure | + | In figure 3 the chemical interactions of a E- and K-coil pair are shown, unfortunately not the pair we have used in the case of our experiments. The wide white arrows depict the interhelical hydrophobic interactions (hydrophobic core)[2]. The thin arrows display the electrostatic attractions of the two coils on each other. As mentioned before these electrostatic interactions are caused by the amino acids present on position '''e''' and '''g'''. In this case glutamic acid (E) and lysine (K). All these interactions greatly contribute to the stability and the prevention of self-dimerization. |

| - | The correct amino acid sequence of the coil pair IAAL E3 and IAAL K3, which we have implemented in our experiments is stated in table 1[2]. | + | The correct amino acid sequence of the coil pair IAAL E3 and IAAL K3, which we have implemented in our experiments is stated in table 1[2]. We chose this pair because we wanted to have a reasonably short coil with only 3 heptad repeats to avoid interference with the quaternary structure of the capsid proteins. |

</p> | </p> | ||

| + | ''Table 1: Amino acid sequence of the chosen pair of coils (in one letter amino acid code)'' | ||

| + | |||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center" | {| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center" | ||

|- style="font-style: italic" | |- style="font-style: italic" | ||

| Line 30: | Line 37: | ||

|Ac-KIAALKEKIAALKEKIAALKE -NH2 | |Ac-KIAALKEKIAALKEKIAALKE -NH2 | ||

|} | |} | ||

| - | |||

| - | ==GFP with E-coil== | + | ==GFP with the E-coil== |

| + | [[File:Gfpcoilhistag.PNG|300px|right|thumb|<p align="justify">''Figure 4: protein folding prediction of GFP (green) with a His-tag (blue) fused to a coiled coil (purple) ([http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K883705 BBa_K883705])]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | In an effort to reduce the amount of laboratory work it was decided to fuse the different capsid proteins of the [[Team:Wageningen_UR/VLPs|VLPs]] with the K-coil only. We designed experiments to add the K-coil to capsid proteins of the Turnip yellows virus ([[Team:Wageningen_UR/ObtainingthePoleroVLP|TuYV]]), the Cowpea chlorotic mottle virus ([[Team:Wageningen_UR/ModifyingtheCCMV|CCMV]]) and to Hepatitis B ([[Team:Wageningen_UR/ModifyingtheHepatitisB|Hepatitis B]]) by fusion PCR (for more information see [[Team:Wageningen_UR/Project|project]] pages). Possible ligands and other proteins of interest are fused with the E-coil. In this way the GFP - E-coil construct for example is of universal use with either of the [[Team:Wageningen_UR/VLPs|3 different viruses]]. The GFP E-coil construct was created by a two-step PCR to add the E-coil to a GFP template (taken from the parts registry). The detailed experimental approach can be found in the following methods section. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Ligandgfp.jpg|200px|center]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | '''Methods''' | ||

| + | |||

<p align="justify"> | <p align="justify"> | ||

| - | + | We designed three primers to obtain the desired construct in 2 subsequent PCR reactions. The E-coil is fused to the N-terminus of the GFP protein additionally we placed a histidine-tag on the C-terminus. | |

</p> | </p> | ||

| - | [[File: | + | [[File:Legend.png|600px|center|thumb|<p align="justify">''Figure 5: legend''</p>]] |

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Steps GFP-coil fusion.png|600px|center|thumb|<p align="justify">''Figure 6: primers designed for the fusion of GFP with the E.coil''</p>]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Steps GFP-coil fusion2.png|600px|center|thumb|<p align="justify">''Figure 7: PCR steps for the fusion of GFP with the E.coil''</p>]] | ||

| + | |||

| - | |||

<p align="justify"> | <p align="justify"> | ||

| - | Next to the E | + | Next to the construct mentioned above, we made a variant of GFP + E-coil without a histidine-tag by using the sequencing reverse primer (which anneals to the backbone) instead of the self-designed backward primer. |

| + | |||

| + | To produce and test our fusion protein, the constructs were both ligated behind an IPTG inducable promoter. The presence of fluorescence was tested by inducing the transformants with IPTG and exposing them with UV light. | ||

| + | In order to make more sensitive measurements fluorescence microscopy was used. | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| - | + | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | '''Results''' | ||

| + | |||

<p align="justify"> | <p align="justify"> | ||

| - | + | After some trouble with the PCR reactions at the beginning, the correct construct was obtained and ligated into [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_J04500 BBa_J04500] (behind an IPTG induced promoter) and sequenced. To make this part available for the Registry of Standard Biological Parts this construct was also ligated into a pSB1C3 plasmid backbone resulting in the biobricks [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K883704 BBa_K883704]and [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K883705 BBa_K883705]) | |

| - | This experimental approach was done only for the BBa_K197022 KILR. We designed 2 primers to anneal directly on the sequence of the KILR coil. | + | After IPTG induction fluorescence could be seen for both transformants containing the biobricks [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K883704 BBa_K883704] (IPTG induced promoter + GFP fused to a coiled coil) and [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K883704 BBa_K883705] (IPTG induced promoter + GFP with a His-tag fused to a coiled coil) (Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11). |

| + | This proves that the GFP is still functioning after the addition of a coil as well as a coil and a Histidine tag. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The functionality of GFP in the fusion protein was also tested and confirmed for the construct in the pSB1AK3 backbone (Figure 8, Figure 11). | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:GFPcoil in AKbb.JPG|500px|left|thumb|<p align="justify">''Figure 8: colonies containing GFPcoil + IPTG promoter [left] and GFPcoil + His tag + IPTG promoter [right] in a pSB1AK3 backbone exposed to UV light. In the middle: control colony that does not produce fluorescence '</p>]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Fluorescence Cbb.png|430px|right|thumb|<p align="justify">''Figure 9: colonies containing BBa_K883704 in DH5α [left; front], BBa_K883705 in DH5α [right; back] exposed to UV light. In the middle: control colony that does not produce fluorescence '</p>]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <html><div style="clear:both;height:1px;"></div></html> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Colour difference.png|400px|center|thumb|<p align="justify">''Figure 10: difference in fluorescence between the colony containing BBa_K883704 and the control'</p>]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p align="justify"> | ||

| + | Using fluorescence microscopy, the intensity of the fluorescence could be measured observed more accurately. | ||

| + | Pictures where taken of each of the tranformants prior IPTG induction (in a liquid culture) as well as after growing on a IPTG containing plate overnight (Figure 11). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Comparing the intensity of the florescence of the positive control (JM109 containing Bba_I13522 - GFP with a constitutive promoter) with the transformants containing our constructs it seems that our GFP-coil fusion protein results in a weaker florescence. However the expression cannot be compared since it is induced by different promoters. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Our negative controls (transformants prior induction) show no fluorescence (Figure 11). | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Fluorescence bricks .jpg|500px|center|thumb|<p align="justify">''Figure 11: fluorescence GFPcoil + IPTG induced promter in pSB1AK3 in BL21, GFPcoil + His tag + IPTG induced promoter in pSB1AK3 in JM109, BBa_K883704 in DH5α, BBa_K883705 in DH5α measured with fluorescence microscopy. On the right side: before induction (sample taken from liquid medium); on the left side: after induction with IPTG (sample taken from a plate) - of each sample a picture was taken once with light microscopy and once with fluorescence microscopy'</p>]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | =="Leucine zipper" coils== | ||

| + | <p align="justify"> | ||

| + | Next to the E-/K-coil combination we are searching for suitable alternatives. We found the EILD/ KILR coils made by UC Berkeley, which are already presented in the Registry of Standard Parts ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K197021 BBa_K197021] and [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K197022 BBa_K197022]). Both coils are GNC4 leucine zippers which can form both homo- and heterodimers. The 2009 iGEM Berkeley wetlab team used this property to show cell-cell adhesion of ''Escherichia coli'' cells, if the coils are presented on the cell surface (Figure 12) [3]. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Berkeley coils.jpg|500px|center|thumb|<p align="justify">''Figure 12: cell-cell adhesion using coiled-coils''</p>]]<!-- --><br /> | ||

| + | <p align="justify"> | ||

| + | Although functionality of these coils was proved in cell-cell adhesion, they were cloned into a BBa_197038 plasmid backbone. This backbone is very unusual for standard registry parts and is not compatible with any of the iGEM cloning standards. To allow future iGEM teams to work with the Berkeley system more easily, we decided to clone the KILR-coil into a standard 10 plasmid backbone pSB1C3. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This experimental approach was done only for the BBa_K197022 KILR. We designed 2 primers containing iGEM standard 10 pre- and suffix to anneal directly on the sequence of the KILR coil. | ||

*FW primer KILR: 5’ GTTTCTTCGAATTCGCGGCCGCTTCTAGAGGATCTGTTAAAGAACTGGAAGACAAAAA 3’ | *FW primer KILR: 5’ GTTTCTTCGAATTCGCGGCCGCTTCTAGAGGATCTGTTAAAGAACTGGAAGACAAAAA 3’ | ||

*BW primer KILR: 5’ TACTAGTAGCGGCCGCTGCAGGAAGAAACCGCAACCACCACGTTCAC 3’ | *BW primer KILR: 5’ TACTAGTAGCGGCCGCTGCAGGAAGAAACCGCAACCACCACGTTCAC 3’ | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

</p> | </p> | ||

| - | == | + | [[File:Robert_KILR_PCR_3-8 2.jpg|250px|left|thumb|''Figure 13: st.10 PCR Berkeley KILR '']][[File:Nicetransf.JPG|250px|left|thumb|''Figure 14: KILR transformation plate with nice red-white screening possibility'']][[File:KILR digestion check.jpg|250px|left|thumb|''Figure 15: KILR linearization '']] |

| + | |||

| + | <br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br> | ||

| + | <p align="justify"> | ||

| + | The digested PCR product was ligated into a BBa_J04450 (RFP coding device) plasmid to allow a red-white screening of the transformed colonies after transformation by electroporation. 5 white colonies checked by digestion, if they yielded a plasmid of the expected size. The gel electrophoresis of figure 15 shows the expected constructs lengths for all samples except for number 4, which was discarded. Sample 1 and 2 were sent for sequencing. Unfortunately, the [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K883600 BBa_K883600] part was sent to parts registry before sequence results revealed that all 2 samples lack a SpeI restriction site. They do, however, contain the full sequence of the KILR coil (about 111bp) and the restriction sites of EcoRI, XbaI and PstI. | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Ideas - possible Epitopes and Ligands == | ||

<p align="justify"> | <p align="justify"> | ||

| - | The parts registry already contains both ligands and epitopes | + | The parts registry already contains a multitude of both ligands and epitopes that could be attached to the [[Team:Wageningen_UR/VLPs|VLPs]] using the PnA-system. An overview is given in the table below. Many of the BioBricks are still 'planning', but the design can be used to attach to the E-coil. |

</p> | </p> | ||

''Table 2 Overview of epitopes and ligands from the parts registry'' | ''Table 2 Overview of epitopes and ligands from the parts registry'' | ||

| Line 141: | Line 219: | ||

|Planning | |Planning | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | |||

---- | ---- | ||

| + | == References == | ||

*1. Minten, I.J., et al., Controlled encapsulation of multiple proteins in virus capsids. J Am Chem Soc, 2009. 131(49): p. 17771-3. | *1. Minten, I.J., et al., Controlled encapsulation of multiple proteins in virus capsids. J Am Chem Soc, 2009. 131(49): p. 17771-3. | ||

*2. Litowski, J.R. and R.S. Hodges, Designing heterodimeric two-stranded alpha-helical coiled-coils. Effects of hydrophobicity and alpha-helical propensity on protein folding, stability, and specificity. J Biol Chem, 2002. 277(40): p. 37272-9. | *2. Litowski, J.R. and R.S. Hodges, Designing heterodimeric two-stranded alpha-helical coiled-coils. Effects of hydrophobicity and alpha-helical propensity on protein folding, stability, and specificity. J Biol Chem, 2002. 277(40): p. 37272-9. | ||

*3. Aguado, G.G.L. Part: BBa_K197022 KILR. 2009 [09/17/2012]; Available from: http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K197022. | *3. Aguado, G.G.L. Part: BBa_K197022 KILR. 2009 [09/17/2012]; Available from: http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K197022. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <div class="prNav"> | ||

| + | <div class="prev"> | ||

| + | <a href="https://2012.igem.org/Team:Wageningen_UR/Project" title="Introduction">1. Introduction</a> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="next"> | ||

| + | <a href="https://2012.igem.org/Team:Wageningen_UR/VLPs#Virus-Like_Particles" title="Virus Like Particles">3. Virus Like Particles</a> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

Latest revision as of 17:37, 26 October 2012

Contents |

The Plug 'n Apply system (PnA system)

A big challenge of our project is the attachment of ligands and functional proteins on either the outside or inside of a virus-like particle (VLP). We decided to use a noncovalent anchor-like system, which consists of two different coiled-coil proteins. We called it the Plug-and-Apply-system (PnA-system). In figure 1 is shown the actual connection of a ligand (yellow color) via the PnA-system (shown in red and green color) to a VLP (light blue colour).

E- and K-coil

For various experiments the E-/K-coil combination IAAL E3 and IAAL K3 reported by Litowksi et al. in 2002 was used.

α-helical coiled-coils represent a widely abundant but simple oligomerization motif in proteins. They have an enormous diversity of functions in nature ranging from motor proteins to transcription factors and chaperones [1]. Coiled-coils are comprised of one single secondary protein structure: the α-helix. Their quaternary structure is stable and does not unfold in aqueous solution at a neutral pH unlike other peptide α-helices. One of the striking structural features of the coiled coils is their build-up of two to five α-helices. These helices contain a heptad repeat of mainly apolar amino acids which is denoted as (abcdefg)^n in literature. The letters a and d are usually amino acids with a highly hydrophobic side chain. The side chains are packed against each other forming a hydrophobic core which allows the formation of a supercoil. Whereas the letter n is representing the number of helices in the final coil. The helices can be identical or even different in sequence and may be aligned in a parallel/antiparallel way. The amino acids of the letters e and g have typically charged residues to allow electrostatic interactions with other peptides (most importantly other coils)[2]. The process of dimerization is largely dependent on the peptide sequence and can be homodimeric (Figure 2.) or heterodimeric (e.g. E- and K-coil). In our project we are utilizing heterodimeric coiled-coils to noncovalently attach proteins. This system is advantageous because of the high stability and specificity. The use of heterodimeric coils additionally prevents the self-dimerization of either the virus capsid monomer or the protein (or ligand) of choice.

In figure 3 the chemical interactions of a E- and K-coil pair are shown, unfortunately not the pair we have used in the case of our experiments. The wide white arrows depict the interhelical hydrophobic interactions (hydrophobic core)[2]. The thin arrows display the electrostatic attractions of the two coils on each other. As mentioned before these electrostatic interactions are caused by the amino acids present on position e and g. In this case glutamic acid (E) and lysine (K). All these interactions greatly contribute to the stability and the prevention of self-dimerization. The correct amino acid sequence of the coil pair IAAL E3 and IAAL K3, which we have implemented in our experiments is stated in table 1[2]. We chose this pair because we wanted to have a reasonably short coil with only 3 heptad repeats to avoid interference with the quaternary structure of the capsid proteins.

Table 1: Amino acid sequence of the chosen pair of coils (in one letter amino acid code)

| name | peptide sequence |

| gabcdefgabcdefgabcdef | |

| IAAL E3 | Ac-EIAALEKEIAALEKEIAALEK-NH2 |

| IAAL K3 | Ac-KIAALKEKIAALKEKIAALKE -NH2 |

GFP with the E-coil

In an effort to reduce the amount of laboratory work it was decided to fuse the different capsid proteins of the VLPs with the K-coil only. We designed experiments to add the K-coil to capsid proteins of the Turnip yellows virus (TuYV), the Cowpea chlorotic mottle virus (CCMV) and to Hepatitis B (Hepatitis B) by fusion PCR (for more information see project pages). Possible ligands and other proteins of interest are fused with the E-coil. In this way the GFP - E-coil construct for example is of universal use with either of the 3 different viruses. The GFP E-coil construct was created by a two-step PCR to add the E-coil to a GFP template (taken from the parts registry). The detailed experimental approach can be found in the following methods section.

Methods

We designed three primers to obtain the desired construct in 2 subsequent PCR reactions. The E-coil is fused to the N-terminus of the GFP protein additionally we placed a histidine-tag on the C-terminus.

Next to the construct mentioned above, we made a variant of GFP + E-coil without a histidine-tag by using the sequencing reverse primer (which anneals to the backbone) instead of the self-designed backward primer. To produce and test our fusion protein, the constructs were both ligated behind an IPTG inducable promoter. The presence of fluorescence was tested by inducing the transformants with IPTG and exposing them with UV light. In order to make more sensitive measurements fluorescence microscopy was used.

Results

After some trouble with the PCR reactions at the beginning, the correct construct was obtained and ligated into [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_J04500 BBa_J04500] (behind an IPTG induced promoter) and sequenced. To make this part available for the Registry of Standard Biological Parts this construct was also ligated into a pSB1C3 plasmid backbone resulting in the biobricks [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K883704 BBa_K883704]and [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K883705 BBa_K883705]) After IPTG induction fluorescence could be seen for both transformants containing the biobricks [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K883704 BBa_K883704] (IPTG induced promoter + GFP fused to a coiled coil) and [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K883704 BBa_K883705] (IPTG induced promoter + GFP with a His-tag fused to a coiled coil) (Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11). This proves that the GFP is still functioning after the addition of a coil as well as a coil and a Histidine tag. The functionality of GFP in the fusion protein was also tested and confirmed for the construct in the pSB1AK3 backbone (Figure 8, Figure 11).

Using fluorescence microscopy, the intensity of the fluorescence could be measured observed more accurately. Pictures where taken of each of the tranformants prior IPTG induction (in a liquid culture) as well as after growing on a IPTG containing plate overnight (Figure 11). Comparing the intensity of the florescence of the positive control (JM109 containing Bba_I13522 - GFP with a constitutive promoter) with the transformants containing our constructs it seems that our GFP-coil fusion protein results in a weaker florescence. However the expression cannot be compared since it is induced by different promoters. Our negative controls (transformants prior induction) show no fluorescence (Figure 11).

Figure 11: fluorescence GFPcoil + IPTG induced promter in pSB1AK3 in BL21, GFPcoil + His tag + IPTG induced promoter in pSB1AK3 in JM109, BBa_K883704 in DH5α, BBa_K883705 in DH5α measured with fluorescence microscopy. On the right side: before induction (sample taken from liquid medium); on the left side: after induction with IPTG (sample taken from a plate) - of each sample a picture was taken once with light microscopy and once with fluorescence microscopy'

"Leucine zipper" coils

Next to the E-/K-coil combination we are searching for suitable alternatives. We found the EILD/ KILR coils made by UC Berkeley, which are already presented in the Registry of Standard Parts ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K197021 BBa_K197021] and [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K197022 BBa_K197022]). Both coils are GNC4 leucine zippers which can form both homo- and heterodimers. The 2009 iGEM Berkeley wetlab team used this property to show cell-cell adhesion of Escherichia coli cells, if the coils are presented on the cell surface (Figure 12) [3].

Although functionality of these coils was proved in cell-cell adhesion, they were cloned into a BBa_197038 plasmid backbone. This backbone is very unusual for standard registry parts and is not compatible with any of the iGEM cloning standards. To allow future iGEM teams to work with the Berkeley system more easily, we decided to clone the KILR-coil into a standard 10 plasmid backbone pSB1C3. This experimental approach was done only for the BBa_K197022 KILR. We designed 2 primers containing iGEM standard 10 pre- and suffix to anneal directly on the sequence of the KILR coil.

- FW primer KILR: 5’ GTTTCTTCGAATTCGCGGCCGCTTCTAGAGGATCTGTTAAAGAACTGGAAGACAAAAA 3’

- BW primer KILR: 5’ TACTAGTAGCGGCCGCTGCAGGAAGAAACCGCAACCACCACGTTCAC 3’

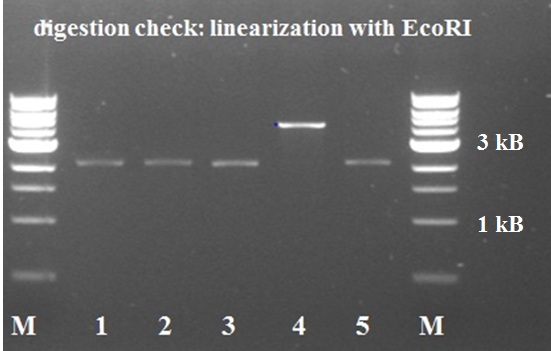

The digested PCR product was ligated into a BBa_J04450 (RFP coding device) plasmid to allow a red-white screening of the transformed colonies after transformation by electroporation. 5 white colonies checked by digestion, if they yielded a plasmid of the expected size. The gel electrophoresis of figure 15 shows the expected constructs lengths for all samples except for number 4, which was discarded. Sample 1 and 2 were sent for sequencing. Unfortunately, the [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K883600 BBa_K883600] part was sent to parts registry before sequence results revealed that all 2 samples lack a SpeI restriction site. They do, however, contain the full sequence of the KILR coil (about 111bp) and the restriction sites of EcoRI, XbaI and PstI.

Ideas - possible Epitopes and Ligands

The parts registry already contains a multitude of both ligands and epitopes that could be attached to the VLPs using the PnA-system. An overview is given in the table below. Many of the BioBricks are still 'planning', but the design can be used to attach to the E-coil.

Table 2 Overview of epitopes and ligands from the parts registry

| Epitopes | Author | URL | Type | Status |

| V5 epitope tag tail domain (GKPIPNPLLGLDST) | Reshma Shetty | http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_T2018 | proteindomain/affinity | Planning |

| V5 epitope tag head domain (GKPIPNPLLGLDST) | Reshma Shetty | http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_T2019 | proteindomain/affinity | Planning |

| V5 epitope tag special internal domain (GKPIPNPLLGLDST) | Reshma Shetty | http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_T2020 | proteindomain/affinity | Planning |

| VSV-G epitope tag tail domain (YTDIEMNRLGK) | Reshma Shetty | http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_T2021 | proteindomain/affinity | Planning |

| VSV-G epitope tag special internal domain (YTDIEMNRLGK) | Reshma Shetty | http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_T2022 | proteindomain/affinity | Planning |

| ITGA4 - B epitope | QGEM_09 | http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K214003 | Null | Available |

| Ligands | ||||

| Delta-mCherry Juxtacrine Signaling Ligand MammoBlock | Grant Robinson | http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K511302 | Null | Planning |

| Delta-mCherry-4xFF4 Juxtacrine Signaling Ligand MammoBlock | Grant Robinson | http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K511303 | Null | Planning |

| Stem cell factor (SCF) or c-kit-ligand | David Charoy | http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K292009 | Null | Available |

| SH3 ligand | John Dueber | http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_J62002 | Null | Planning |

| SH3 ligand | John Dueber | http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_J62003 | Null | Planning |

References

- 1. Minten, I.J., et al., Controlled encapsulation of multiple proteins in virus capsids. J Am Chem Soc, 2009. 131(49): p. 17771-3.

- 2. Litowski, J.R. and R.S. Hodges, Designing heterodimeric two-stranded alpha-helical coiled-coils. Effects of hydrophobicity and alpha-helical propensity on protein folding, stability, and specificity. J Biol Chem, 2002. 277(40): p. 37272-9.

- 3. Aguado, G.G.L. Part: BBa_K197022 KILR. 2009 [09/17/2012]; Available from: http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K197022.

"

"