Team:Cambridge/Project draft

From 2012.igem.org

Contents |

Project

Parts for a reliable, cost-effective, biosensing standard

Introductory Video:

Aim

The fundamental aim of this project is to develop parts towards a standard for biosensors that allows high accuracy and reliability, whilst being cost-effective, practical and straightforward to use, even for users with no biological background. We hope that our work will be particularly useful to environmental scientists or health workers.

Background

Electronic circuits excel at logic and speed of computation, but aren't particularly flexible when it comes to sensing the a wide-range of small molecules. The use of biosensors as an approach to determining concentrations of analytes in samples for a huge variety of applications (medical, doping, ground water contamination - See human Practices) has great potential to be revolutionary technology.

Currently, however, whilst plenty of biosensors exist and have been characterised to a greater or lesser degree, they are in no way unified or standardised. Not only that, they are almost exclusively either non-quantitative or only usable in the lab, read using expensive and delicate plate-readers. They are also limited, as is often the case in synthetic biology, by the stochasticity of life, often giving unreliable or poorly reproducible results. Furthermore, very little thought has gone into the storage and distribution on biosensors for use in the field where shelf life, cost of transportation, storage conditions and biocontainment all become important factors

We aim to develop a new standard for biosensors that tackles all these issues. The standard is to be back-compatible, so not only will new biosensors developed with the standard have these properties, but so will pre-existing sensors after minimal adaptation.

The standard consists of five parts:

1. Use of a ratiometric reporter system

Biosensors may give unreliable outputs. This is due to differences in the number and state of the cells from test to test. By including an internal control signal, to which another inducible signal may be normalised, the reliability and reproducibility of a sensor may be significantly improved. We are currently working on two such two-signal systems. Firstly, a construct that uses an inducible eCFP and a constitutively expressed eYFP. All components, save the vector, are existing biobricks. This will serve as a proof of concept and a way of testing old and new sensors. However, this will require a platereader to use. Our second construct will not, as described below.

2. Use of bacterial luciferase

Luciferase light emission is visible to the naked eye, and can therefore be sensed and quantified using inexpensive, off-the-shelf electronic components, giving it an advantage over fluorescent proteins in this context

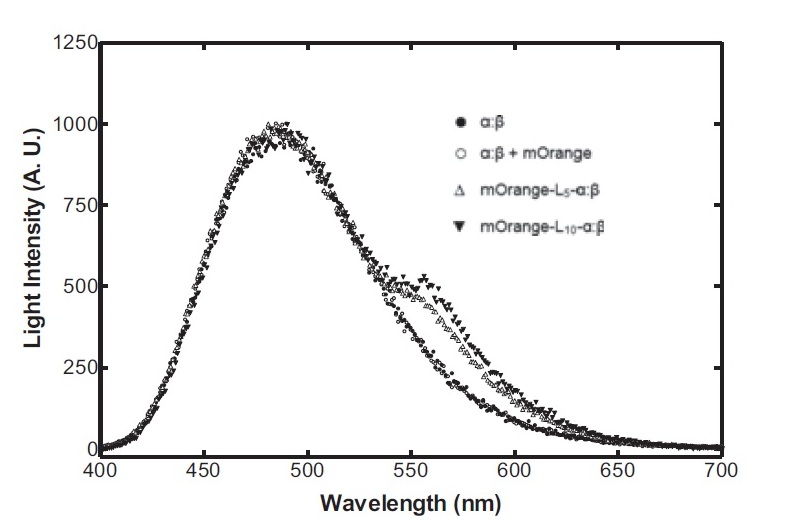

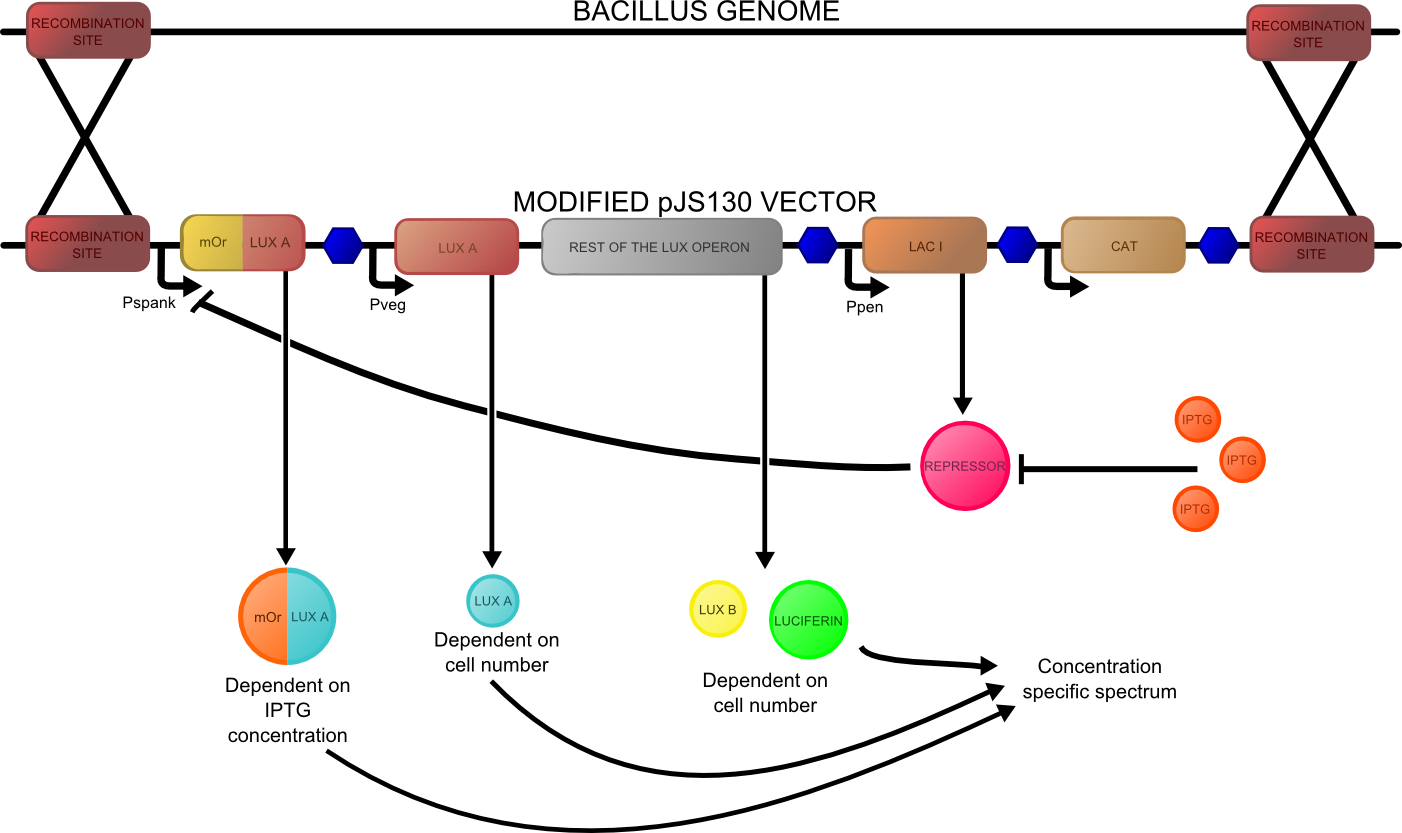

Bacterial luciferase has a major advantage over other luciferases in this context in that the substrate regeneration enzymes are known and included in the operon. Other luciferases require addition of exogenous luciferin, which is expensive and unstable at room temperature for any significant length of time. The major problem is the lack of colour change variants of bacterial luciferase for the second signal. We are investigating two possibilities for the colour variant. Firstly, a fusion of the luxA subunit with mOrange, a fluorescent protein. This has recently been shown (Dachuan Ke1 and Shiao-Chun Tu, 2011) to result in an additional peak on the emission spectrum at 560 nm, compared to the natural peak at 490 nm. Secondly, a natural accessory YFP for the Vibrio fischeri luciferase, isolated from a yellow bioluminescent strain, which shifts the peak to longer wavelengths and increases the intensity.

In either case, an unaltered lux operon would be expressed constitutively. Either the accessory protein or the mOrange fusion would be expressed inducibly, and a ratio taken between the two peak intensities.

3. Development of a cheap and easy sensing kit

We are developing a cheap kit for quantification of the lux-based ratiometric construct. All components are inexpensive and readily available. It is self-contained, based on arduino, and will be compatible for use with a PC or an android smartphone, for ease of use in the field.

4. Development of new biosensors and adaptation of old biosensors

It is important that this standard is compatible with existing biobrick sensors. Therefore, we have selected a few biosensors to adapt to and characterise with our constructs. Additionally, we are investigating new and novel biosensors. We have decided to use riboswitches, as they are not represented in the registry and may become more widely used in the future. We have obtained fluoride and magnesium riboswitches to characterise and adapt.

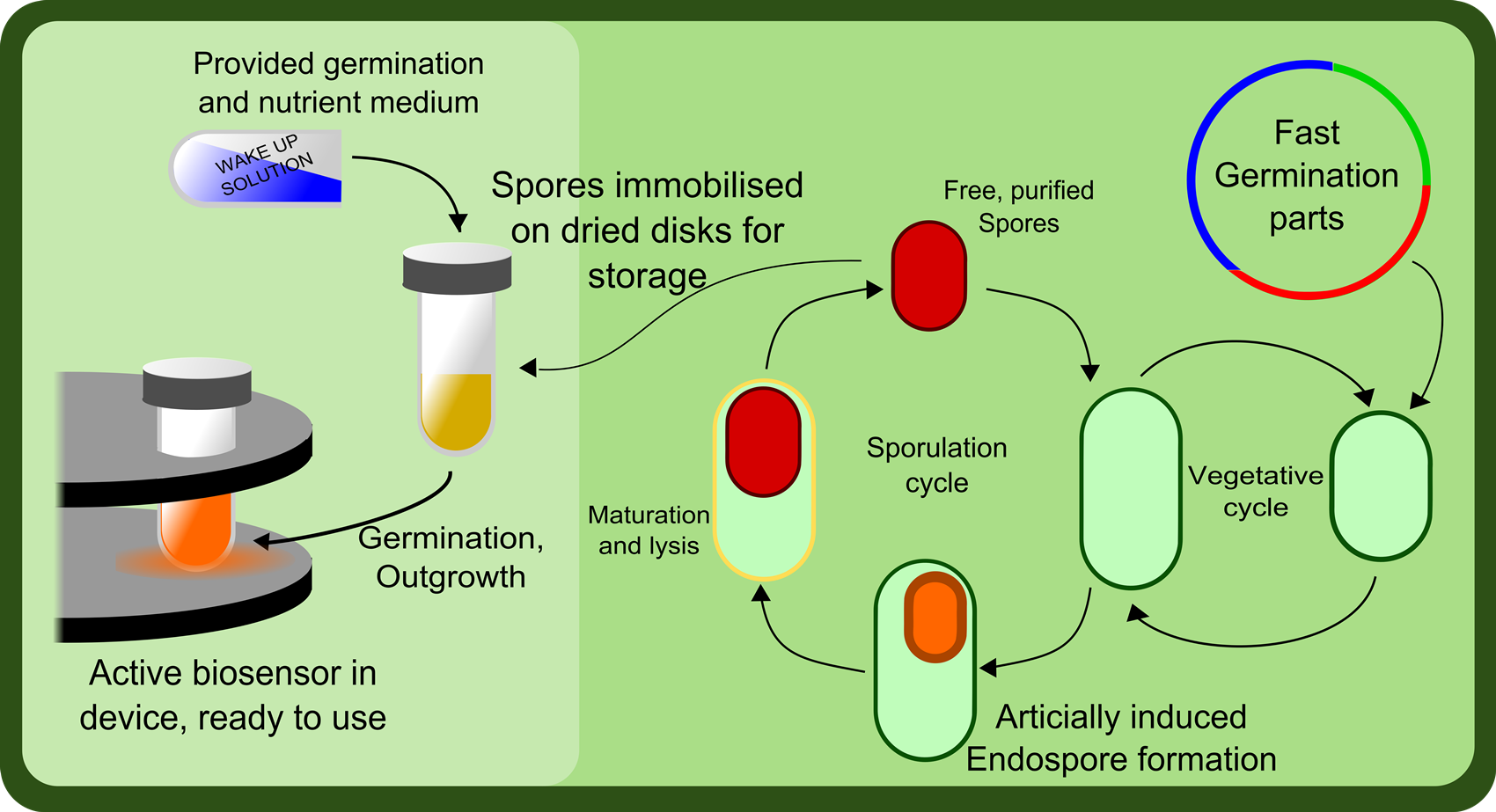

5. Development and use of a custom quick-germination strain of Bacillus subtilis

Bacillus subitilis forms extremely hardy spores, which can be kept at room temperature on desiccated medium. Compared to E.coli, which must be kept in a freezer or freeze-dried for transport, the practical benefits of using subtilis are self-evident. We have isolated genes in subtilis that can be overexpressed to considerably shorten germination time.

Project Details

As stated above, the main aim of the project was to develop a bio-sensing standard to promote a platform for the development of novel biosensors that may work in a wealth of different ways but that can all be characterised and coupled to an output that is predictable, reliable and most importantly meaningful.

Standardised Outputs

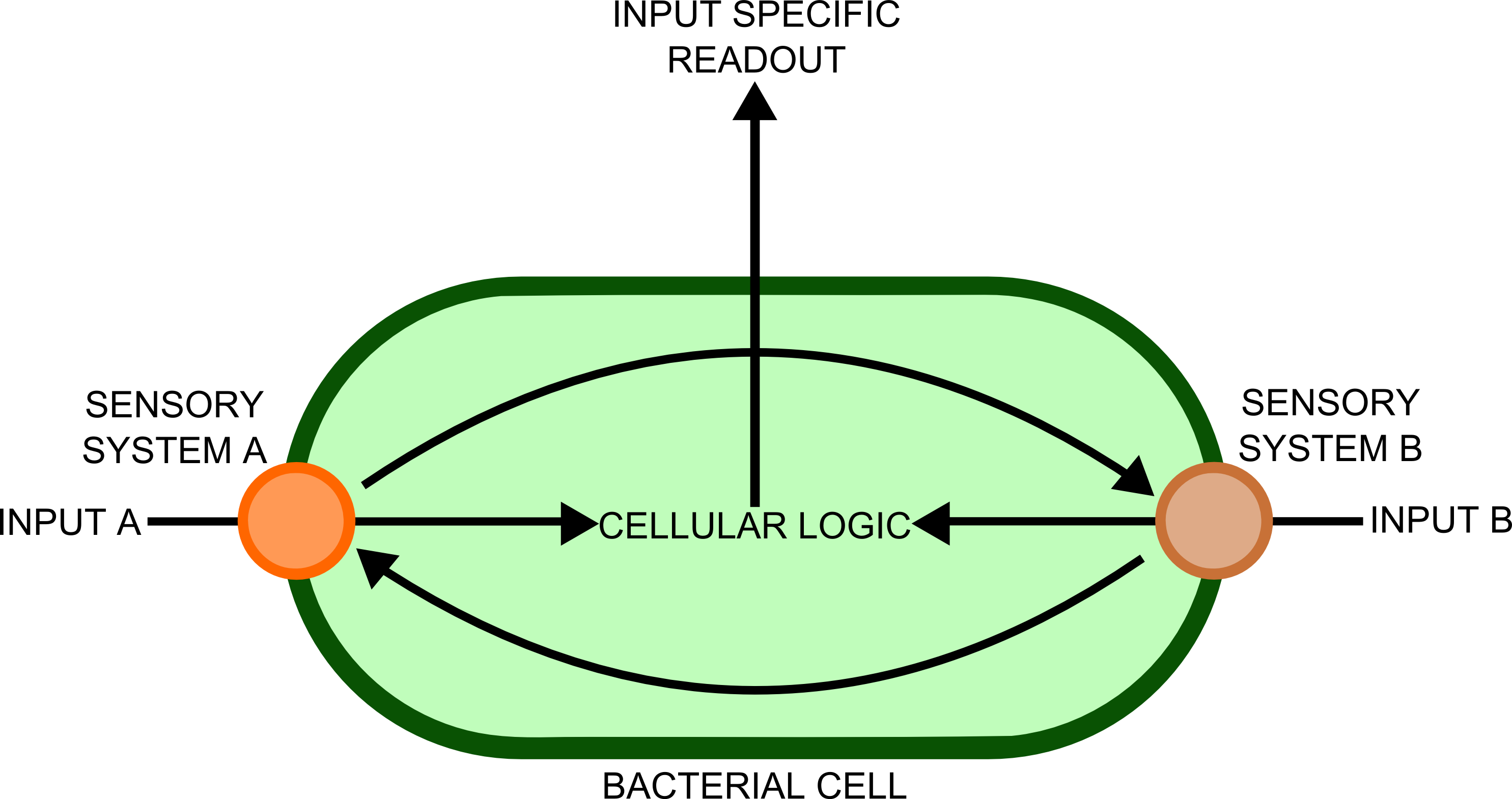

The use of biosensors within synthetic biology has one main advantage over traditional, electronic sensors, which is the diversity of chemical signals to which these finely tuned nanomachines can respond to. The ability of the cells to integrate and process information sensed in this way is powerful, but presently the complexity of the metabolic pathways used by cells for this confounds attempts at synthetic in vivo information processing. Until we have a far more complete picture of the interactions between cellular components that allow information processing (something which may be provided in the future by the field of Systems biology), the use of electronic circuits will remain a far more powerful and simple means of processing such information.

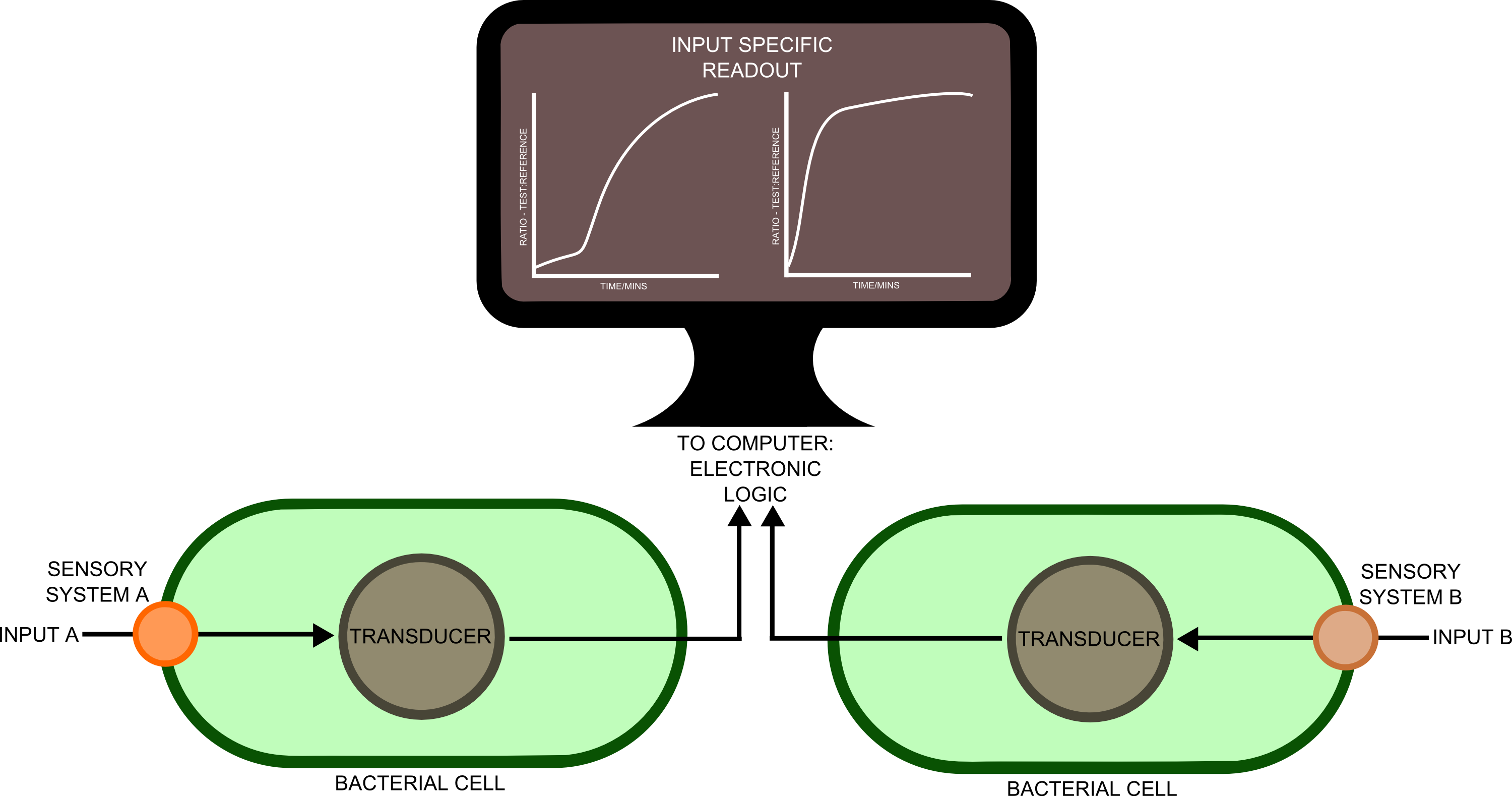

In order to transfer such information to a computer would require a biological - electronic interface. This implies that the bacteria would send a message of some sort, which will be detected by an electronic sensor. Many different cell types, each containing a complement of genes suitable for detecting ]a particular substance, would be used in different spatial locations. Separation of the different genes into different cellular compartments would prevent crosstalk between the different sensory cascades, improving the reliability and predictability of the constructs produced.

In order to best implement these principles, we have decided that every biosensor should be coupled to a standard output with its own response curves, to suit the customer's needs. Decoupling the culture/analyte solution from the detection system (e.g. an electronic one) would be a good idea as otherwise the behaviour of the electrode under different conditions might affect the results. Therefore we chose to use light as the signal transducer. This left us with a choice between biofluorescence and bioluminescence.

Whilst fluorescent proteins have been characterised in far greater detail than luciferases, part of the broader aim of the project is for the kit to be as affordable as possible. And given that the equipment to detect the emission spectra of luciferases is cheaper, we decided that a quantitative measurement of bioluminescence was a better option.

One of the greatest problems we seek to overcome in this project is that of consistent readouts. As is always the case with biology, predictability in our biosensing equipment was going to be an issue. To normalise for cell density productivity, it was decided that a ratiometric output would be absolutely necessary if the output from our biosensors was to be meaningful. Drawing on work done by James Brown and the Haseloff lab into reliable, predictable and quantitative ratiometric measurements using fluorescent proteins, we decided to use these principles as the basis of our work with luciferase. We also decided that, as a side experiment and proof of concept, we would attempt to achieve meaningful ratiometric outputs with fluorescent proteins that could be measured with an (all too expensive!) plate reader.

On the luciferase side of things, after a fairly deep trawl through the literature, an OFP-luciferase fusion was found where the emission spectra appeared sufficiently distinguishable from that of the normal bacterial luciferase (a fairly distinctive blue) that it could be measured using simple photo-resistors and coloured filter gels. The emission spectra of the OFP/luciferase fusion is shown below:

The construct that we hope to make is shown below:

Biosensors

As the main crux of this project is a standardised output, we aimed to develop several biosensors, employing different mechanisms, to prove the extended functionality of the final product. To date, most of the biosensors in the registry use an inducible promoter to control expression of their reporter protein. We have used some of these as a proof of the compatability of our kit with a theoretical customers' sensors. However, we also explored another mechanism of biosensing in the form of riboswitches. These have the potential to be the detectors of the future providing a more standard way of designing input circuits and hopefully a faster sensing method as the transciption has already occurred (unlike inducible promoters).

The sensors:

Instrumentation

We have constructed a mechanical rotary device that is turned by an arduino-controlled motor to 'sense' from 6 different cuvettes that can be placed in the device and then left for automated detection. The arduino is also connected to two light sensors, one supplied with a blue and the other with an orange filter. The ratio of the light intensity at blue and orange frequencies can be measured to determine the strength of output signal from the bacillus.

The hardware is coupled to a graphical user interface (GUI) that was designed using wxpython. Python is particularly useful as the communication with the arduino microcontroller is done using serial programming, for which python has standard libraries. However, before any communication takes place between the user and the device, the arduino is loaded to perform the basic functions which are written in C++. The arduino and python were chosen for the ease of use and open platform. Also, the arduino is cheap and python is free!

Sporulation and Germination

Another aspect to this project is the longevity of the product. Strains of bacteria expressing various receptors would be generated and stored as dormant spores. This allows the individual tubes of bacterial 'sensors' to sit in the user's cupboard until needed. When the user requires a specific sensor, the appropriate strain is selected and the bacteria can be germinated by following a simple protocol. They can then be placed into the arduino device, the sample loaded and the concentration profile measured.

Part of the main reason for choosing Bacillus subtilis as our chassis was because of it's abiltiy to form dormant spores. As part of our project, we aim to determine a protocol for inducing sporulation in Bacillus, and determine a very simple protocol for germinating the spores so they can be used as part of the system.

It is essential for the germination procedure to be as straight forward as possible, requiring minimal equipment and expertise, so that it could in theory be performed in the field, in a situation where the biosensor might be used.

Results

-->

"

"