Team:LMU-Munich/Germination Stop/Knockout

From 2012.igem.org

How do Sporulation & Germination Work?

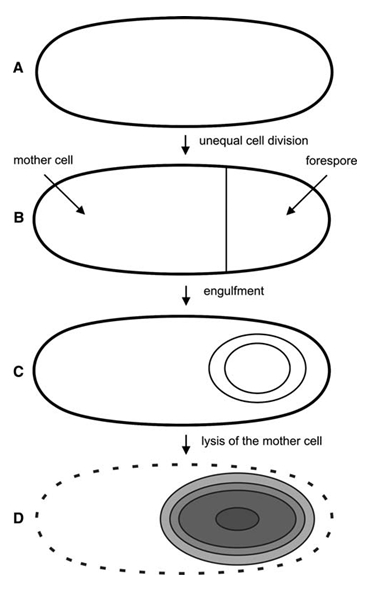

Sporulation: The Bacillus life cycle can include both classic division as well as reproduction by sporulation and spore germination. In response to nutrient starvation, Bacillus cells form endospores in a process called sporulation (Fig. 1). The “mother” cell forms the endospore within its own cytoplasm. The endospore contains its DNA in the spore core, which is protected by several layers of coats. The outermost layer is the spore crust. The spore is very dry, and contains a substance called dipicolinic acid (DPA), which replaced water to protect the DNA. Until the spore hydrates and swells out of its protective coats, it is resistant to a wide variety of environmental stressors, including UV radiation, toxic chemicals, freezing, high heat, dessication, and pH extremes. This resistance to stressors allows the spore to survive almost indefinitely until conditions are again ideal for growth.

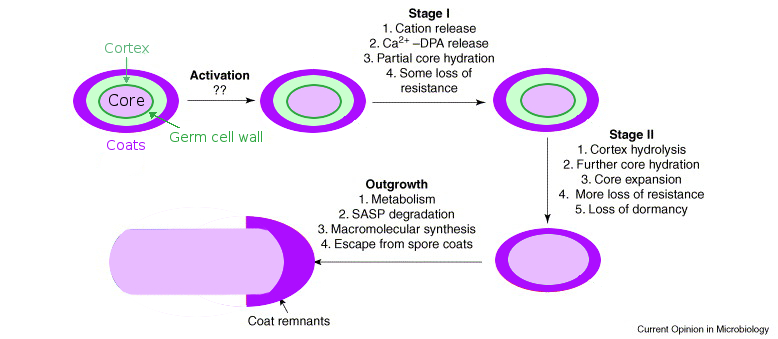

Germination: On its inner spore membrane, the spore has germinant receptors. The spore coats are believed to be semipermeable or porous, in order to permit the passage of germinants to the receptors. When germinants such as amino acids and sugars reach the receptors, the spore begins the biophysical process of germination (see Fig. 2). Initially, the spore replaces its DPA with water (Stages I and II in Fig. 2), shifts its pH (Stage I), and swells (Stage II). Lytic enzymes break down the rigid spore coat layers encapsulating the spore's core (Stage II), allowing the spore core to swell further and begin the outgrowth process into a vegetative cell (Outgrowth). When the spore coat is broken down by lytic enzymes, the spore's environmental resistance is lost. For our project, we wish to prevent this germination process.

|

How do Germination Gene Knockouts Work?

Our idea of how to prevent germination from occurring is to knock out genes encoding functions involved in the germination process. There are a huge number of genes which play a role in germination, but our goal was to select a few very essential genes to knock out.

Based on the research of others, the genes we chose were cwlJ, sleB, cwlB, gerD, and cwlD. Past works of [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19554258 J. Kim and W. Schumann (2009)] and [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11466293 B. Setlow et al. (2001)] showed:

cwlJ and sleB: when knocked out together, germination frequency was reduced by 5 orders of magnitude. Both genes code for lytic enzymes which are active in the process of germination.

gerD and cwlB: When knocked out together, germination frequency was reduced by 5 orders of magnitude. The gerD product plays an unknown role in nutrient germination; the product of cwlB plays a role in cell wall turnover & cell lysis. Note: after several attempts to knock out cwlB, and yielding cells unable to grow or cells growing at a very slow rate, we decided that knocking out cwlB would not be prudent for the production of Sporobeads, as it would delay all experiments in the GerminationSTOP module.

cwlD: When knocked out, germination occurred at a rate of 0.003 to 0.05%. This gene codes for recognition components for cleavage by the germination-specific cortex lytic enzymes.

By knocking out all five of these genes, our goal was to yield a B. subtilis strain which produces spores completely incapable of germination. Germination is stopped during the process of spore coat breakdown. Without the lytic enzymes to break down the coat, the spores should be unable to outgrow into the vegetative stage.

Table 1: Literature values extracted from [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19554258 J. Kim and W. Schumann (2009)] and [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11466293 B. Setlow et al. (2001)]

.| Germination Genes | Encoded Function | Mutant Germination Rate |

|---|---|---|

| gerD | Unknown role in nutrition germination | Reduction by 5 orders of magnitude |

| cwlJ | Germination-specific lytic enzymes | 0.003 – 0.05%

No ATP detected |

| sleB | Germination-specific lytic enzymes | 0.003 – 0.05%

No ATP detected |

| cwlD | Recognition component for lytic enzymes | 0.003 – 0-005% |

Germination Gene Knockout Success!

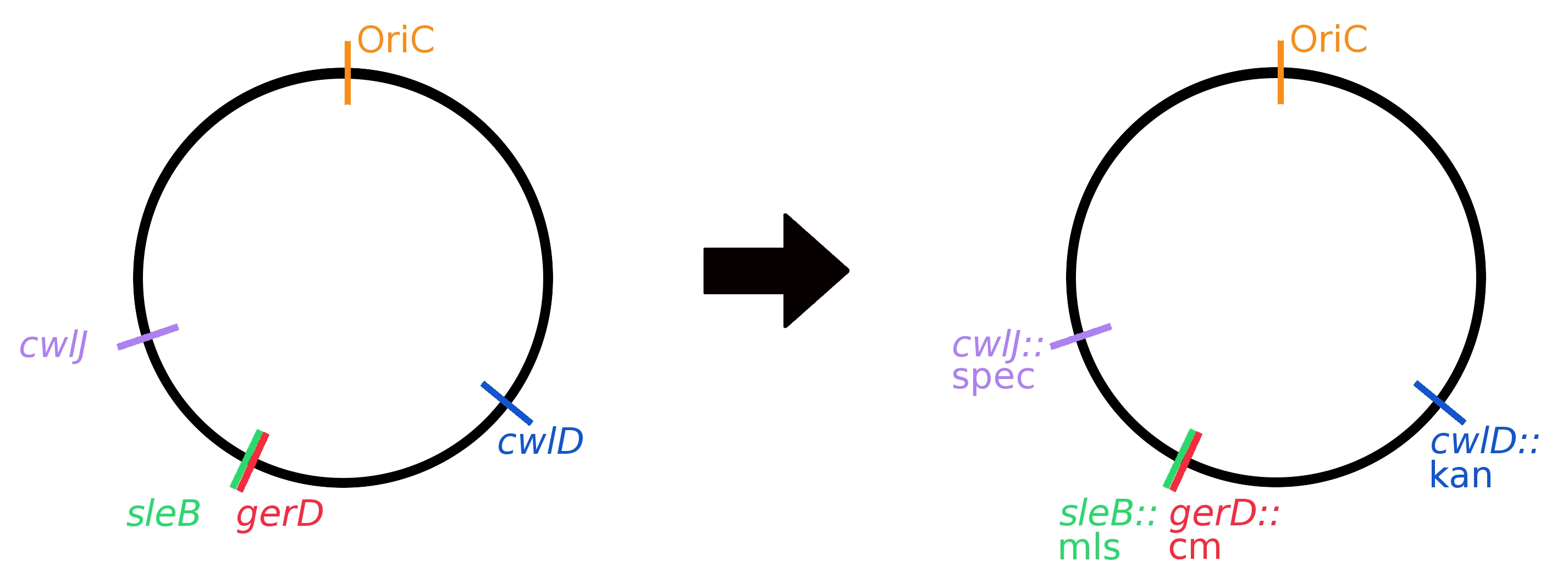

Two methods were employed to knock out germination genes: replacement by resistance cassettes and clean deletions. Resistance cassette knockouts were generated by using long-flanking homology PCR (see Protocols). Single knockouts were created first using different resistance cassettes; then they were combined to create multiple knockouts. A graphical representation of the genome with all gene replacements can be seen in Fig 3.

|

The germination rate of our mutants was checked with a germination assay, shown in Fig. 4. The assay was developed based on published protocols ([http://www.amazon.co.uk/Molecular-Biological-Methods-Bacillus-Microbiological/dp/0471923931/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1348709578&sr=8-1 Harwood, Cutting (1990) Molecular Methods for Bacillus subtilis. Wiley]).

|

We were able to achieve germination rates as low as <1 in 4.6x109 spores in our triple mutant B43. Other mutants also showed extremely reduced germination ability. A table of germination rates of our mutants and all of the other spectacular results can be found on our results page. Our single mutants were not checked in the germination assay. The double and triple mutants tested showed mixed results, with some unable to germinate, and others maintaining low germination abilities. Our quadruple mutants demonstrated no ability to germinate, even in several separate germination assays.

Despite this success, safety was a top priority for this project. In the event that some small percentage of spores retained the ability to germinate, the Suicideswitch subproject (below) prevents outgrowth into viable vegetative cells.

"

"