Team:Freiburg/Project/Experiments

From 2012.igem.org

Experiments

Gene activation

This reporter system gives us a couple of advantages over standard EGFP or luciferase systems. First of all, the SEAP is secreted into the cell culture media, therefore we don't have to lyse our cells for measuring, but just take a sample from the supernatant. We are also able to measure one culture multiple times, e.g. at two different points in time. Another advantage is the measurement via photometry which makes the samples quantitively comparable. Interestingly, we did not have to clone a TALE binding site upstream of the minimal promoter (which would be required for other DNA binding proteins) but simply produced a TALE that specifically bound to the given sequence.

This reporter system gives us a couple of advantages over standard EGFP or luciferase systems. First of all, the SEAP is secreted into the cell culture media, therefore we don't have to lyse our cells for measuring, but just take a sample from the supernatant. We are also able to measure one culture multiple times, e.g. at two different points in time. Another advantage is the measurement via photometry which makes the samples quantitively comparable. Interestingly, we did not have to clone a TALE binding site upstream of the minimal promoter (which would be required for other DNA binding proteins) but simply produced a TALE that specifically bound to the given sequence.

Experimental design

The experiment was done with four different transfections, either no plasmid, only the TAL vector, only the SEAP plasmid or a cotransfection of both plasmids. The cells were seeded on a twelve well plate the day before in 500µl culture media per well. The transfection was done with CaCl2 after a cell culture course protocol written by the lab of Professor Weber.

The experiment was done with four different transfections, either no plasmid, only the TAL vector, only the SEAP plasmid or a cotransfection of both plasmids. The cells were seeded on a twelve well plate the day before in 500µl culture media per well. The transfection was done with CaCl2 after a cell culture course protocol written by the lab of Professor Weber.

Results

The Toolkit

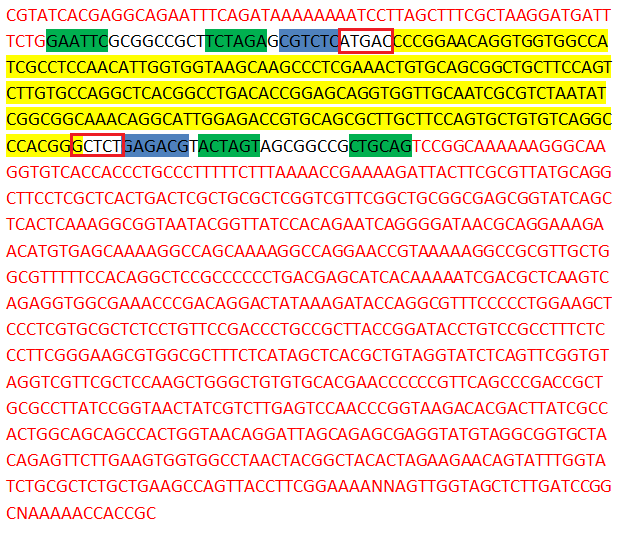

The creation of a toolkit with 96 different parts not only means a lot of labwork but also a lot of organisational tasks, sequencing and analysis. We don't want to bore you with the 96 sequences of our finished biobricks, but we want to give you one example of a finished biobrick and highlight some of the interesting and important strips in its sequence. If you are interested in the other sequences, just have a look at our parts section or go to the [http://partsregistry.org Registry of Standard Biological Parts].

|

In this sequence of our biobrick AA1, the main features of all our biobricks are highlighted. As pointed out in the Golden Gate Standard section of our project description, all direpeat plasmids are submitted in the Golden Gate Standard, that was developed by us and which is fully compatible with existing iGEM standards. In yellow you can see the direpeat gene fragment itself, the green parts are iGEM restriction sites (a requirement for all biobricks), the sequence written in red is part of the psb1C3 vector, the blue sequences are recognition sites for BsmB1 and the red boxes are the cutting sites of BsmB1.

Creation of TAL sequences - Golden Gate Cloning

Admittedly, our GATE assembly kit is a little larger than the kit published from the Zhang kit in Nature this year (the latter comprises 78 parts). But considering that future iGEM teams can easily combine the parts to form more than 67 million different effectors, we believe that it was worth the effort. Now, to get from the toolbox to the finished TAL effector, you only need a few components: six direpeats, one effector backbone plasmid, two enzymes and one buffer. If you mix these components and incubate in your thermocycler for 2.5 hours, you get your custom TAL effector. To put this in perspective: The average turnaround time for TALE construction with conventional kits is about two weeks! In the following sections, we want to show you the efficiency of our GATE assembly platform

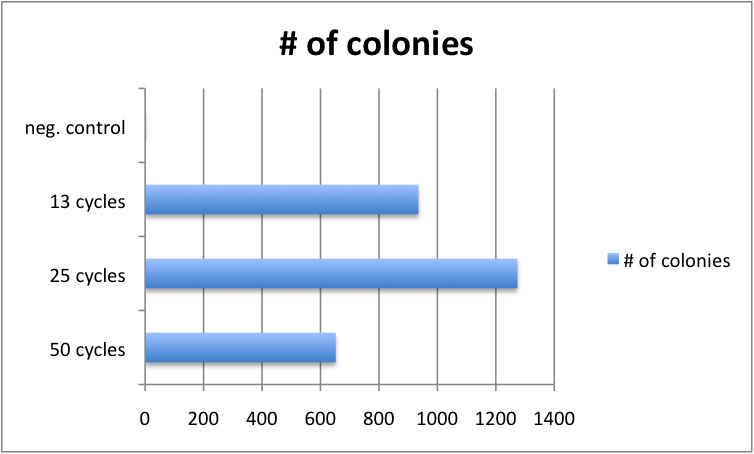

Varying Cycle number of GATE assembly has limited effect

Golden Gate protocols published so far for multistep TALE assembly differ significantly in the number of digestion-ligation cycles performed. To asses, whether the cycle number significantly affects outcome, we performed 4 different GATE assemblies, each with three different cycle numbers (50, 25 and 13 cycles). We did not see significant differences in the number of colonies for the three cycle numbers. Consequently, from that point on, we performed GATE assembly with only 13 cycles (which only take approximately 2.5 hours instead of 8.5 hours for 50 cycles).

|

Direpeat Amplification by Colony PCR

The figure clearly demonstrates the difference in size between the amplicons of negative control (kill cassette still in the vector) and positive (direpeats have replaced the cassette) samples. While lane 2 shows a negative result with a single band of bigger size, all the other samples yielded amplicons of smaller length and thus are considered as positive due to amplification of direpeats.

Nevertheless, it is obvious that the colony PCR did not produce one single product when amplifying the direpeats, but rather a smear consisting of amplicons with varying lengths.

This effect is due to numerous homologies within the direpeats and has previously been described by Briggs et al.1 .

To eliminate those homologies to the greatest extent possible, we changed codon usage within our direpeats. Nevertheless, as the results of our colony PCR demonstrate, there is still a profound amount of homologies left, which imposes difficulties on the amplification of the direpeats array by PCR and instead results in a smear.

Thus, the existence of this smear indicates the presence of direpeats within the expression vector. Moreover, the light bands at 1276 bp indicates, that the right number of direpeats have been inserted into the vector. We performed 30 colony PCRs from colonies of different GATE assemblies and had no negative results (but in some cases, we could not determine the hight of the light band). Since positive results in colony PCR of TALEs do not exclude wrong order of direpeats, we sequenced 28 clones of different GATE assemblies and analyzed the results: in 27 of the 28 clones, sequencing results entirely matched the right sequence. So the efficiency of GATE assembly is approximately 96 %.

The figure clearly demonstrates the difference in size between the amplicons of negative control (kill cassette still in the vector) and positive (direpeats have replaced the cassette) samples. While lane 2 shows a negative result with a single band of bigger size, all the other samples yielded amplicons of smaller length and thus are considered as positive due to amplification of direpeats.

Nevertheless, it is obvious that the colony PCR did not produce one single product when amplifying the direpeats, but rather a smear consisting of amplicons with varying lengths.

This effect is due to numerous homologies within the direpeats and has previously been described by Briggs et al.1 .

To eliminate those homologies to the greatest extent possible, we changed codon usage within our direpeats. Nevertheless, as the results of our colony PCR demonstrate, there is still a profound amount of homologies left, which imposes difficulties on the amplification of the direpeats array by PCR and instead results in a smear.

Thus, the existence of this smear indicates the presence of direpeats within the expression vector. Moreover, the light bands at 1276 bp indicates, that the right number of direpeats have been inserted into the vector. We performed 30 colony PCRs from colonies of different GATE assemblies and had no negative results (but in some cases, we could not determine the hight of the light band). Since positive results in colony PCR of TALEs do not exclude wrong order of direpeats, we sequenced 28 clones of different GATE assemblies and analyzed the results: in 27 of the 28 clones, sequencing results entirely matched the right sequence. So the efficiency of GATE assembly is approximately 96 %.

Activation of transcription

In theory, the TAL domain should bring the fused VP64 domain in close proximity to the minimal promotor to activate the transcription of the repoter gene SEAP. The phosphatase is secreted an acummulates in the cell culture media. After 24 and 48 hours, we took samples from the media, stored them at -20°C, and subjected them two to photometric analysis.

In theory, the TAL domain should bring the fused VP64 domain in close proximity to the minimal promotor to activate the transcription of the repoter gene SEAP. The phosphatase is secreted an acummulates in the cell culture media. After 24 and 48 hours, we took samples from the media, stored them at -20°C, and subjected them two to photometric analysis.

As it is observable in the graph, co-transfection of cells with TAL and SEAP plasmids (++) yielded a high increase in SEAP activity, compared to the control samples. The graph shows the average value of three biological replicates with its standard deviation. We further performed a t-test (Table) to prove if our experiment is statistically significant. The yellow highlighted fields show the p-values for our double transfections. As it is clearly observable, the p-values range below a value of 0,05 which indicates that our TAL transcription factor is able to elevate the transcription of the SEAP gene in a statistically significant manner.

After addition of pNPP, the substrate of SEAP, the activity of SEAP was measured over a period of time. In the next image, the results of the first nine minutes of this measurement are shown. After this time, the OD of the double transfection (++) rose too high to be measured by our photometer. As it is clearly visible, the sample with the double transfection shows a profound increase in the OD. This points to the fact that great amounts of SEAP have been secreted into the cell culture media due to elevated gene expression. In the other samples almost no SEAP activity was measureable. The sample transfected with only the SEAP plasmid showed the highest OD but this effect was not statistically significant (p-value:0,25/0,51).

In the samples, that had been taken 48h after double transfection, the same effects could be demonstrated.

Furthermore, we reapeated the same experiment for a second time. The corresponding data can be viewed here:

Reference

1. Briggs, A. W. et al. Iterative capped assembly: rapid and scalable synthesis of repeat-module DNA such as TAL effectors from individual monomers. Nucl Acids Res (2012).doi:10.1093/nar/gks624

"

"