Team:Washington/Flu

From 2012.igem.org

“For the first time in history we can track the evolution of a pandemic in real time. Influenza viruses are notorious for their rapid mutation and unpredictable behaviour.”--Margaret Chan, WHO Director General

Goal[Top]

We aimed to further optimize the binding of HB80.4 to the group 1 HAs, but knowing that HB80.4 was already broadly binding to many HAs, we wanted to focus our efforts on the flu binder HB36.5 which until had not yet been tested against any other HAs is group 1. Therefore, we wanted to test HB36.5 against the other group 1 HAs and asses its native binding capabilities. After testing, we discovered that in addition to HA1, HB36.5 bound to H5, H5, H9 and H13. Binding was observed to HA2 or HA12. We then proceeded create subtype specific flu binders for these two HAs. Having two broadly – binding flu binders, with subtype specific capabilities would allow for enhanced rapid and reliable global tracking of current and future Influenza strains.There are 16 subtypes of Hemagglutinin. They are divided into two groups based on their phylogenicity.

Background

The influenza virus, also known as the flu, is a deadly virus that has decimated large populations of various species including humans. Even with the advent of vaccinations, high rates of mortality still occur because of the constant evolution of the virus. Variations within each strain of influenza are found within the viral surface proteins that coat their surfaces. One such protein is Hemagglutinin (HA), which is represented by the H when describing flu subtypes (H1N1, H2N3, etc). Hemagglutinin is primarily involved in viral transfer as it mediates the binding and entry into a host cell through a sialic acid linkage. Each strain of Influenza is characterized by it's variant of Hemagglutinin. There are 16 known subtypes of Hemagglutinin; these subtypes give rise to the vast multitude of strains that exist to today and usually only differ by a relatively few number of amino acid mutations. The World Health Organization uses the history of influenza breakouts to predict upcoming strains which could threaten to cause future pandemics and vaccinations are made using these predictions.

In 2011, Fleishman et al., detailed two small proteins which had binding capabilities to various subtypes of hemagglutinin. In 2012, Whitehead et al., optimized the flu binders and showed that HB80.4 was broadly binding, meaning it bound to multiple HAs with high affinity. They also showed that HB36.5 bound preferentially to HA 1.

Methods [Top]

Design: Method of computational design

Gathering information about the structures of Hemagglutinin

Since we wanted to improve the binding of HB80.4 and HB36.5 to specific HAs, we had to understand the structural differences of the many subtypes of hemagglutinin. Initially, we searched for specific hemagglutinin structures on the [http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/home/home.do Protein Data Bank] (PDB). If we found the desired hemagglutinin structures, we downloaded the associated PDB file and made a model of the binder-HA complex in Pymol. These model would then later be used in [http://fold.it/portal/ Foldit].

If we could not find the exact structure of a particular hemagglutinin, we then searched for the protein sequence of that hemagglutinin on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (www.ncbi.nih.gov). We then aligned the protein sequence of the structurally unknown hemagglutinin we obtained to that of the H1 HA (which has a known structure) by using [http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/ Clustalw2]. Next, we created homology models in FoldIt of the desired hemaggluttinin by changing the side chains of the H1 HA in Foldit according to the protein sequence differences we found.

Using the computational application Foldit to design our models

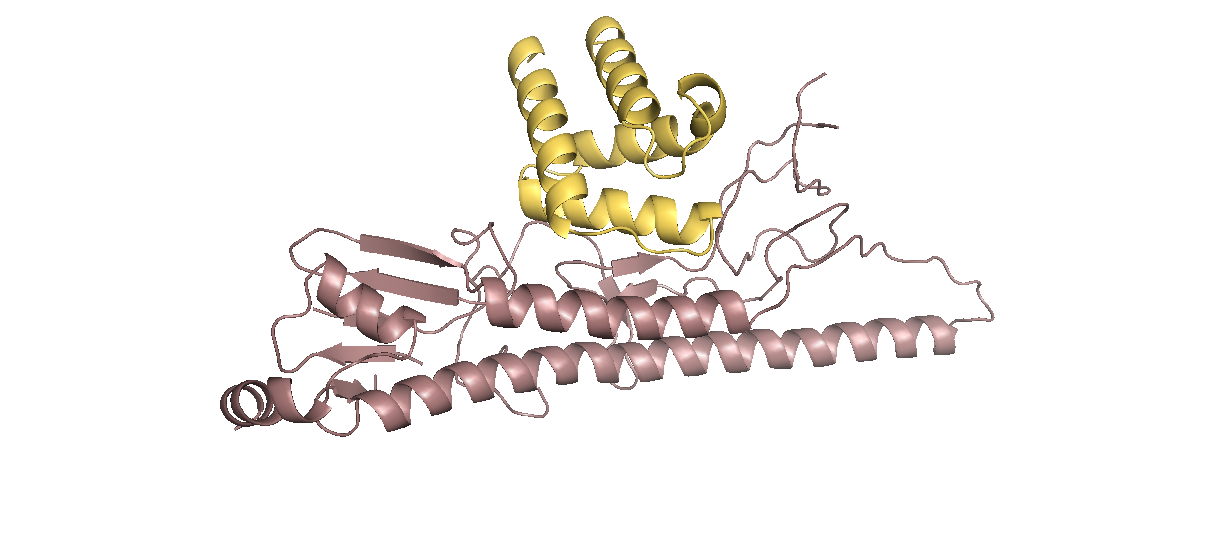

Crystal stuctures of HB36.3 and HB80.4 in complex with H1HA are available on the PDB as PDB ID 3R2X and 4EEF, respectively. To create models our the binder bound to different HAs, we aligned our alternative HA structures to the H1HA in the published crystal structures using PYMOL. Then, we would record the difference in side chains between that specific hemagglutinin and H1HA and use FoldIt to implement those changes on the known crystal structures. The models we created are linked below:

| File:HB80 H12 model.zip | File:HB80 H9 model.zip | File:HB80 H5 model.zip | File:HB36 H13 model.zip | File:HB36 H12 model.zip |

|---|

| File:HB36 H9 model.zip | File:HB36 H6 model.zip | File:HB36 H5 model.zip | File:HB36 H2 model.zip |

|---|

Proposing Mutations based on FoldIt Models

After preparing the FoldIt model, we proposed mutations on the original flu binder in order to improve its binding to the desired hemagglutinin. There is a score total in FoldIt which indicates the energy of the whole protein structure. It is our understanding that the protein structure is more stable when its energy is lower. Thus, our primary goal was to decrease the score total in FoldIt. We did that in three different ways, filling the holes, making space, and balancing the electrostatic. Holes that did not exist in H1HA would be created with the replacement of different side chains. We would mutate the corresponding side chain on the flu binder so that it extends out and fill a hole on the hemagglutinin. Making space is the exact opposite of filling the holes. Some side chains of certain hemaggluttinins would be more projected out in space than that of hemagluttinin one. Therefore, we would mutate the corresponding side chains of the flu binder in order to provide room for the more extended side chains. Some variations of side chain on hemaggluttinin causes some electrostatic changes. We would mutate the corresponding side chains of the flu binder so as to counter balance the electrostatic changes. For example, if a certain area on the helix is changed to be more electronegative, we would introduce an electropositive side chain on the flu binder for improving the binding and vice versa.

Build: Kunkel Mutagenesis - Mutagenizing HB80.4 and HB36.5 flu binders

Kunkel mutagenesis is a classic procedure for incorporating targeted mutations into a plasmid and we use it to create many variants of original starting flu binders.

The proteins tested were encoded on the shuttle vector pETCON which contained the yeast display components and was compatible with expression both in E. Coli (bacteria) and S. Cerevisiae (Yeast). This allowed us to do Kunkel Mutagenesis in E. Coli and not have to switch vectors when we transform into yeast in the testing phase of our experiment when we perform Yeast Surface Display.

The first step to producing our specially designed flu binders was to change the original flu binding protein with our desired amino acid substitutions.

We designed mutagenic oligonucleotide primers that would anneal to the original flu binding protein and incorporate point mutations that, when expressed, would result a variant of the binder with the desired amino acid shift.

To incorporate these mutations, we first isolated single stranded DNA (ssDNA) of our vector harboring the original binding sequence. To do this we infected cells with bacteriophage M13, which packages its own ssDNA genome identified by length, and so in tandem packaged our vector in single stranded form. We then harvested the phage from the lysed culture of E. Coli, and extracted our single stranded vector DNA.

Next, we annealed and extended our mutagenic oligos to incorporate the specified mutations into the newly synthesized antisense strand. This hybrid vector was transformed into E. Coli that degraded the original uracil-containing DNA and replaced it with sections complementary to the mutagenized strand.

Test: Yeast Surface Display

To test our designs, we transformed our mutants into the organism Saccharomyces cerevisiae in order to have a more stable cell line for surface display and binding efficiency analysis. We then used yeast surface display, a method adapted from Boder and Wittrup (1997) [3]. This method allowed us to analyze a subset of our constructs at 4 different antigen (HA) concentrations: 0,1, 10, and 100 nM. In this process, our mutant plasmids were first expressed in yeast and grown in SDCAA growth media. Next, cells were grown in SCGAA media which contained glucose and galactose, required for the activation of the galactose inducible promoter on the yeast plasmid. This allows the mutant plasmid to be expressed on the yeast surface. All yeast cell samples were standardized to an OD600 of 2, and then labeled using different amounts of a single type of biotinylated antigen (HA). After an incubation step, the samples were then washed to remove unbound antigen. The samples were then labeled with Streptavidin-PE (to monitor binding of antigen, see in red in the diagram below) and anti-cymc FITC (to monitor surface expression, seen in green in the diagram below).

We then analyzed the fluorescent signature of the yeast cells using flow cytometery. Flow cytometry beams a laser into a stream of the samples containing the mutant and uses fluorescence detectors to measure the volume of fluorescently labeled cells. This generates graphs of the mean PE fluorescence of the surface displaying the population of cells as a function of antigen, and the KD is calculated that fits to that data assuming 1:1 binding stoichiometry.

Results Summary [Top]

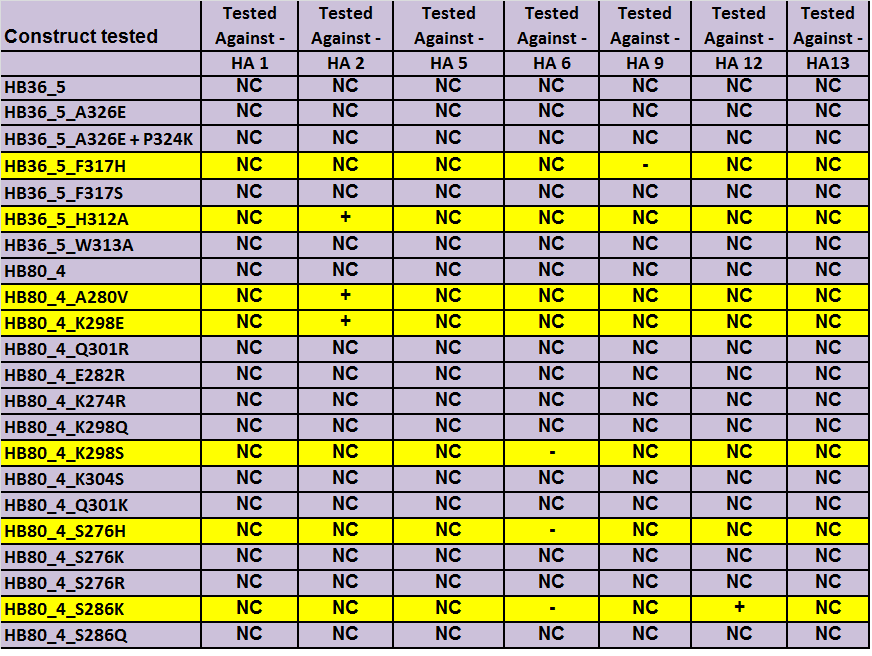

We were able to design and test 6 HB36.5 variants and 14 HB80.4 variants. Including the starting designs we tested over 150 binder/HA combinations (see below spreadsheet). The results showed that most of the suggested mutations we found did not change the binding affinity to the different hemagglutinins. However, we did find 7 variants (listed below the table), that had an effect on binding. Our most dramatic results were with HB36.5 H312A, which was able to bind H2HA strongly where the original design variant could not. H2HA is particularly important as it has not been seen in humans since 1958. As it is known to still circulate in birds and has the potential to cross back over into humans it can be considered a future pandemic strain. We hope that our mutations to HB36.5 will be useful in a diagnostic that can rapidly test for the presence of H2 hemagglutinin which would be useful in global health monitoring. We have not been able to find any other protein that can differentiate between H1(the most common) and H2HA and believe we have created the first such example.

HB36.5_F317H was predicted to increase HA5 binding but it decreased the binding to HA9. Nevertheless, it can be used for specific hemagglutinin subtypes binder.

HB36.5_H312A was predicted to increase HA2 binding and it did improve binding to HA2.

HB80.4_A280Vwas predicted to decrease HA2 binding but it improved the binding to HA2.

HB80.4_K298E was predicted to increase HA2, HA5, HA6 and HA12 binding and it did improve binding to HA2.

HB80.4_S276H was predicted to increase HA6 binding but it decreased the binding to HA6.

HB80.4_K298S was predicted to increase HA12 binding but it decreased the binding to HA6.

HB80.4_S286K was predicted to increase HA12 binding and it increased the binding to HA12. However, it decreased the binding to HA6.

Future Directions [Top]

We intend to combine the HB36.5 single-point mutants H312A and W313A, both successfully having increased binding to HA2, to create a superior combinatorial mutant with multiple-fold improvement. Simultaneously, we intend to create a mutant of HB36.5 that will bind H12 preferentially, as HB36.5 does not currently do so. After obtaining a version of HB36.5 that binds to HA12 more efficiently, a diagnostic system can be made to track the types of hemagglutinin on the surface of influenza. Specifically, this system can identify HA2 and HA12 from the 16 subtypes of hemagglutinin.

Parts Submitted [Top]

Flu Binders submitted six parts to the registry: Starting HB80.4 and HB36.5 Flu binders and four of our promising mutants. A short description for each part is provided below.

[http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K892405 BBa_K892405: Starting HB80.4]

[http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K892401 BBa_K892401: Starting HB36.5]

[http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php/Part:BBa_K892403 BBa_K892403: HB36.5_H312A]

A mutated HB80.4 flu binder aimed to increase binding to H2, a subtype of hemagglutinin on the surface of Influenza. This mutant has a point mutation at residue 312 from Histidine to Alanine.

[http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part: HB36.5_F317S]

[http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part: HB36.5_A326E]

References[Top]

[1] Whitehead, Timothy, et al. "Optimization of affinity, specificity and function of designed influenza inhibitors using deep sequencing." Nature Biotechnology 30.6 (2012):543-548.

[2] Fleishman, Sarel, et al."Computational design of proteins targeting the conserved stem region of influenza hemagglutinin." Science 332.6031 (2011): 816-821.

[3] Boder, Eric and Wittrup, Dane. "Yeast surface display for screening combinatorial polypeptide libraries." Nature Biotechnology 15.6 (1997):553-557.

"

"