Team:Marburg SYNMIKRO/Project

From 2012.igem.org

Contents |

Summary

We aimed to establish a system in Escherichia coli cells that generates a large number of novel proteins by combinatorial fusion of subfragments. Our project was inspired by the VDJ-recombination of the vertebrate immune system. There, a limited number of protein coding sequences is used to generate the enormous diversity of antibodies. We designed A and B modules containing different protein coding subfragments to be recombined. Fusion of one A fragment with one B fragment is achieved by the site-specific DNA recombinase Gin of bacteriophage Mu. Recombination sites were arranged as direct repeats thus causing deletions upon recombination. Gin catalyzed recombination depends on the presence of an enhancer element.This enhancer was placed together with the suicide gene sacB between the A and B modules. This design guarantees that recombination automatically stops when the central fragment is deleted. To test our system and to visualize the combinatorial activity we fused fluorescent proteins of different color to different intracellular localization domains. We expect that after successful recombination E. coli cells will glow in different colors located at different positions within the cell.

General goal

The development of novel proteins and the Improvement of existing ones by genetic engineering has a tremendous impact on our daily lives. We all benefit from advances in this field be it for medical, industrial or environmental applications. The central goal of our project is the random generation of novel protein variants. The Marburg_SYNMIKRO team 2012 has created ˈThe Recombinatorˈ: an intelligent Genetically Engineered Slot Machine (iGESM). "The Recombinator" can be used to produce large numbers of novel proteins by combinatorial fusion of functional domains.

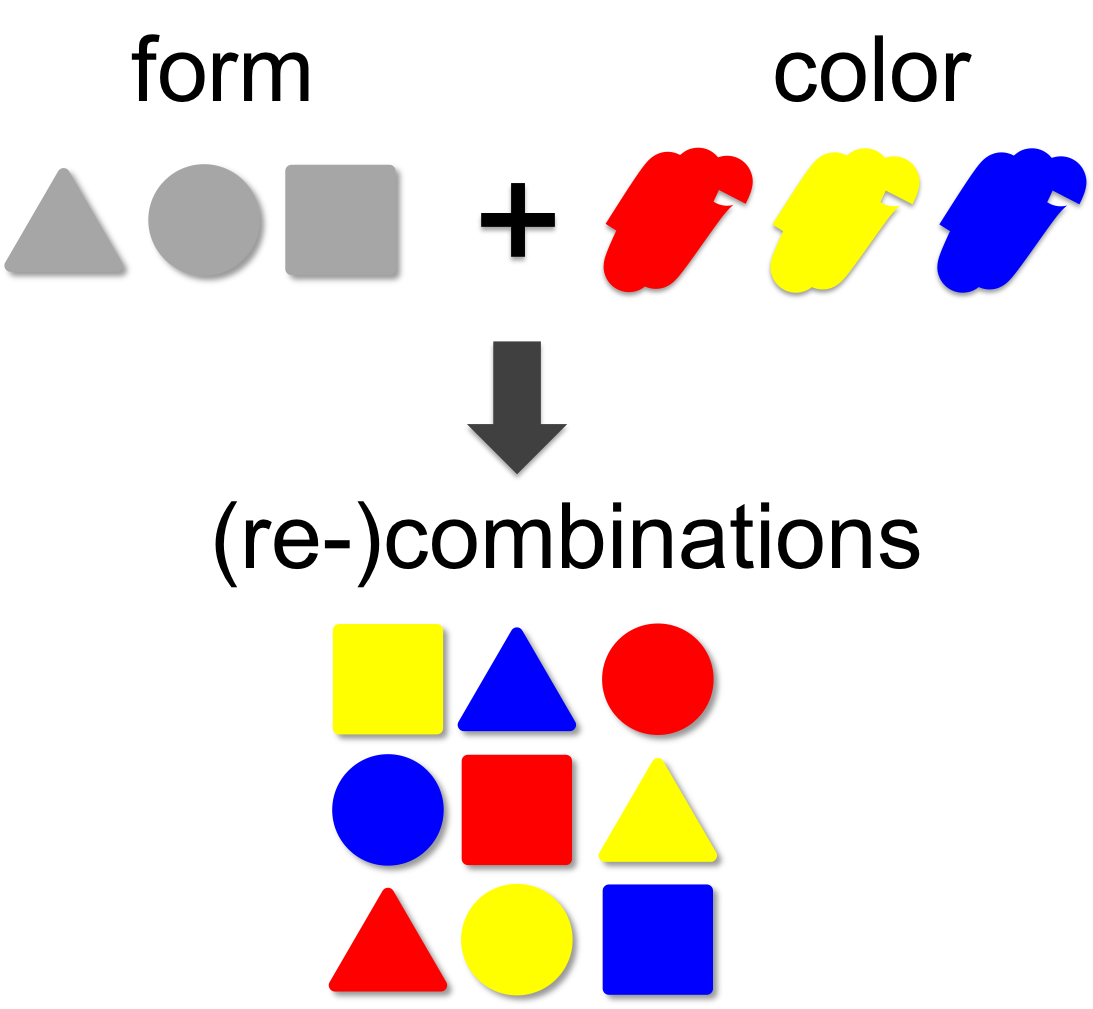

Combinatorics

In mathematical theory the number of possible combinations results from the multiplication of elements. In our example (left) we combine three forms (triangle, square and circle) with three colors (red, blue and yellow). This results in 3 x 3 = 9 different combinations. A practical example for the power of combinatorics is visualized on our team page, where you can enlarge the size of the iGEM team by generating additional team members through recombination of the existing ones. By this method a total of 12 x 12 x 12 = 1,728 novel mixed-up team members can be designed.

Recombination in the adaptive immune system

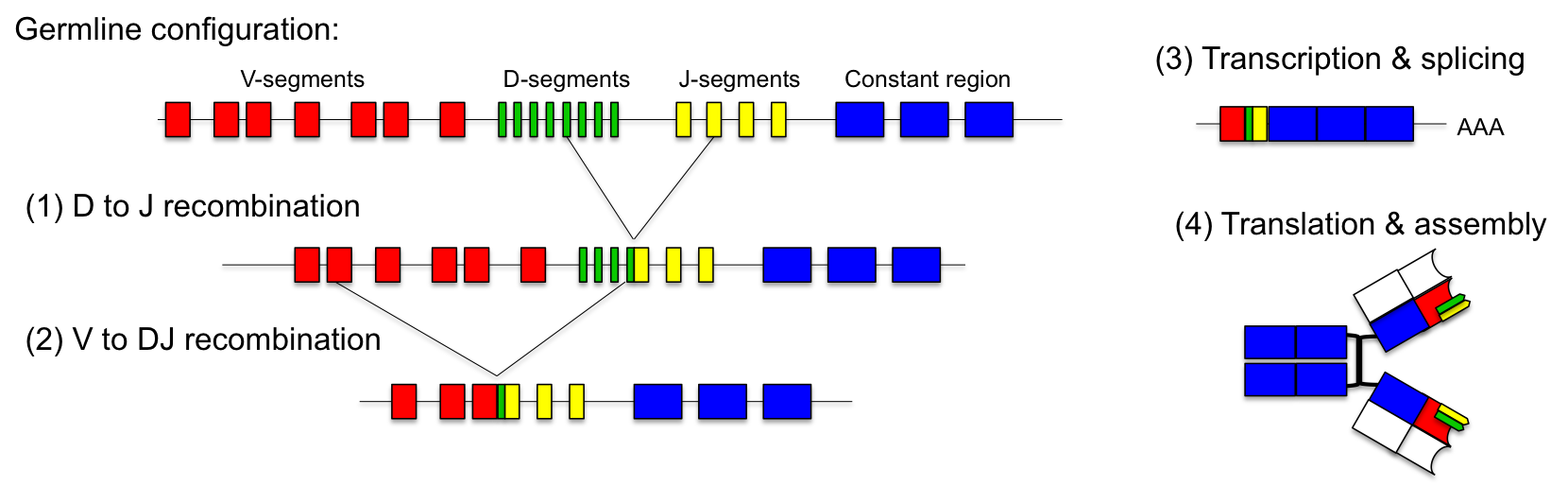

Our "Recombinator" system for the generation of novel fusion proteins in vivo was inspired by the generation of antibody diversity via VDJ-recombination. The enormous number of different antibodies is generated by recombination of a limited number of segments that are recombined to form functional antibody chains. This occurs in the B-cells of the immune system and is essential for the recognition of specific antigens.

Antibodies consist of two heavy and two light chains which are covalently connected by disulfide bonds. Both, the heavy and the light chain can be subdivided into constant and variable regions. The variable parts confer the ability to recognize specific antigens. During our life, the immune system is confronted with thousands of different antigens from bacteria, viruses and other microorganisms. This raises the question how antibody diversity is generated during development.

Nature has invented an ingenious solution to this problem: the combinatorial design of the variable regions of the antibodies. In the germline, the genetic locus of the light chain consists of up to 40 V-segments and 5 J-segments. The heavy chain contains 50 V-, 27 D- and 6 J-segments. During maturation of the immune system antibodies are generated by random fusion of these segments.This process is called VDJ-recombination and is catalyzed by the DNA recombinases (RAG-1 and RAG-2).

For the light chain, one V-segment gets fused to one of the J-segments by recombination. The production of the variable heavy chain occurs in two steps. Initially, one of the J-segments is fused to the D-segment (1). Then, the combined DJ-sequence is added to one of the V-segments (2). The recombined antibody gene is transcribed together with the constant part of the antibody, which is added as exon by splicing (3). Heavy and light chains are assembled into functional antibodies (4). Stability of the secreted antibodies is reached by covalent disulfide bonds between heavy and light chains. Since each antibody is generated by combinatorial fusion of one of 40 V-segments, 5 J-segments for the light chain and one of 50 V-, 27 D- and 6 J-segments for the heavy chain, the number of possible combinations amounts to 1.6 x 106. Furthermore, during the recombination process additional mutations are introduced. This increases the number of possible rearrangements to more than 1010.

Site-specific genetic recombination

Genetic recombination is essential to maintain the integrity of large genomes. Double strand breaks in the DNA are repaired by the process of homologous recombination which is conserved from bacteria to man. During sexual propagation homologous recombination occurs during meiosis and creates genetic diversity by exchanging DNA segments between chromosomes.

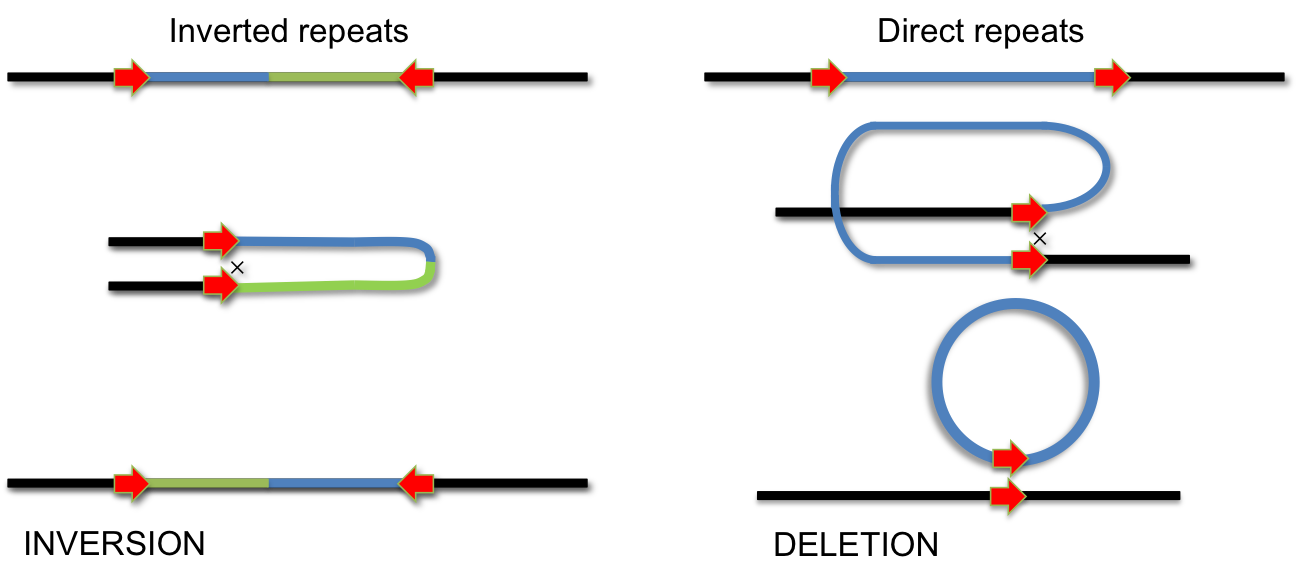

In addition to homologus recombination, several site-specific DNA recombination systems have evolved. Site-specific recombination is used for integration of phage lambda, phase variation of pathogenic Salmonella strains, for VDJ-recombination during antibody development and for several other biological processes, which involve specific DNA rearrangements. In all these cases, specialized enzymes recognize short DNA sequences flanking a segment of DNA. Recombination occurs by cutting and religating these short elements. Depending on the orientation of recombination sites, this process either results in INVERSION or DELETION of the intervening DNA segment. If the recombination sites are arranged as inverted repeats, the segment is inverted; if they form direct repeats, the intervening segment will be removed by recombination.

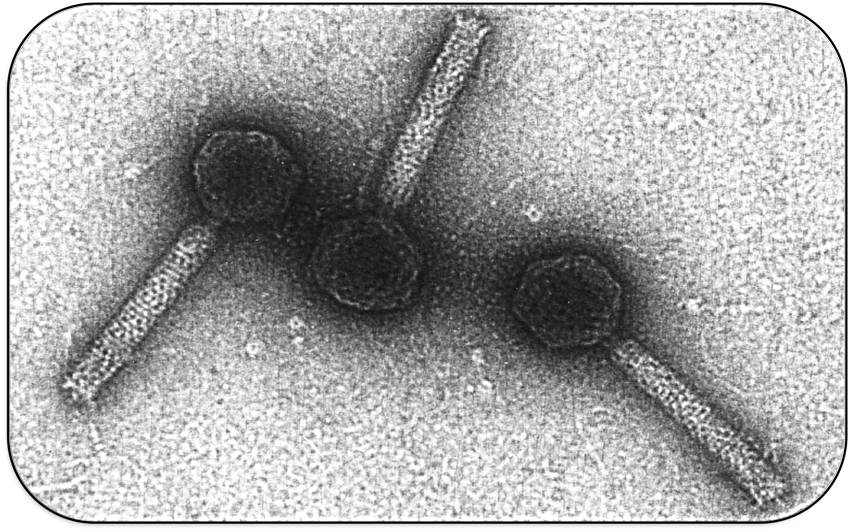

Phage Mu

The bacteriophage Mu is a temperate bacterial virus which has an unusual lifestyle. During lytic phase it propagates in the bacterial host cell by replicative transposition. During lysogenic phase it also behaves like a transposon and integrates into the host genome at a random position. This results in the occurrence of genetic mutations and hence the phage got its name ("mutator phage"). This has been used to construct small derivatives (mini Mu) which can be used for tagging mutagenesis.

Interestingly, phage Mu has a broad host range and can infect very different types of bacteria. Recognition of different hosts by the phage depends on the expression of specific tail proteins (S and U) which are located in the phage genome on the invertible G-segment. Dependent on the orientation of the G-segment, G(+) or G(-), different versions of the tail proteins S and U are expressed and recognize different lipopolysaccharides in the cell wall of bacteria.

Gin recombination

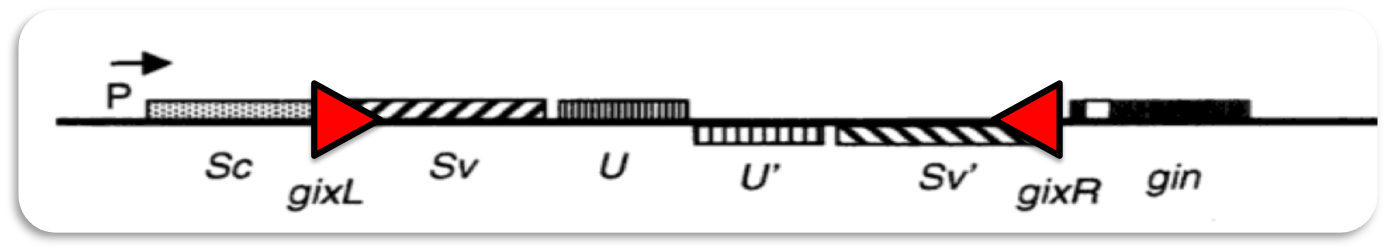

The invertible G-segment of bacteriophage Mu contains two genes, S and U, which are transcribed from a common promoter located outside the G-segment. Depending on its orientation either S and U or S' and U' are expressed.

Inversion of the G-segment is catalyzed by the site-specific DNA recombinase Gin which is encoded on the phage genome. The gin gene is located adjacent to the G-segment. Gin invertase binds to the short gixL and gixR recombination-sites flanking the G-segment. Recombination between these inverted sites results in inversion of the G-segment.

Enhancer

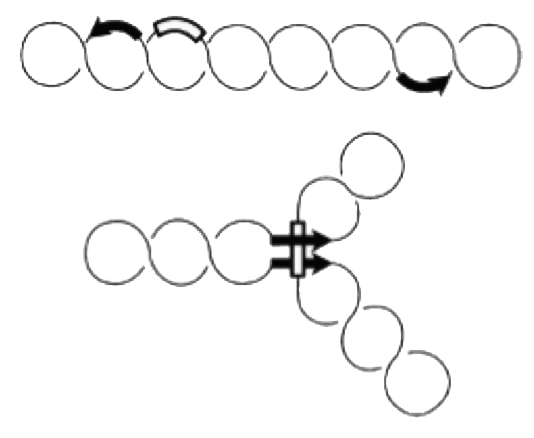

Site-specific recombination catalyzed by Gin recombinase requires the formation of a synaptonemal DNA-protein complex with aligned recombination sites (below).

Efficient recombination occurs only in the presence of a recombinational enhancer (open rectangle) which is located within the inverted DNA segment. The enhancer is bound by the bacterial protein FIS, which stimulates formation of the synaptonemal complex.

Construct

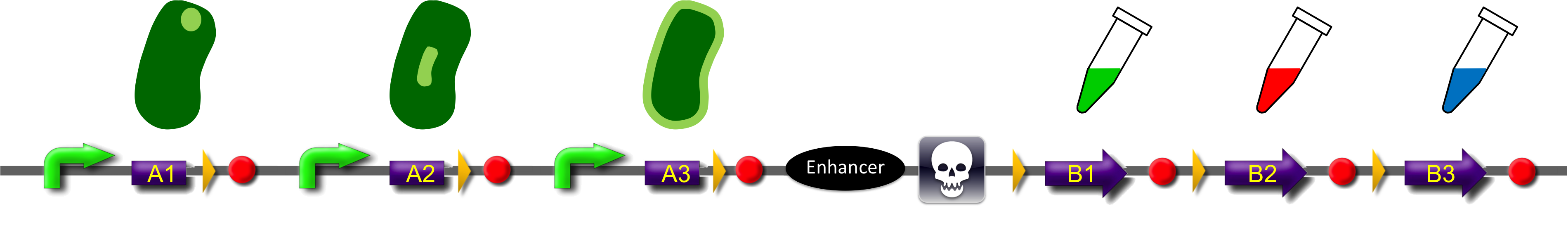

ˈThe Recombinatorˈ is able to recombine diverse protein domainsresulting in expression of chimeric proteins. The system is based on the site-specific Gin recombination system of bacteriophage Mu. Efficient recombination between two gix sites (yellow triangles) requires the presence of an enhancer element (Klippel et al., 1993). To demonstrate the proof-of-principle of our system we placed the enhancer element between bacterial intracellular localization domains (the A-modules) and the fluorescent proteins GFP, CFP and mRFP (B-modules). Due to this design recombination terminates after deletion of the central segment. This guarantees that our system generates a random fusion of one A-module with one B module.

Each localization domain is preceded by a promoter and ribosomal binding site.

The A-modules were taken from the bacterial HU, GroES and Amidase C proteins. These proteins are targeted to the cell pole, the periplasm and the nucleoid, respectively (Bernhardt et al., 2003; Wery et al., 2001; Li et al., 2012). Each A-module is followed by a recombination site (gixR). For expression of the fusion conbstructs we used a constant promoter (biobrick [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_J23108 BBa J23108]) Thus we added a gix-site after every A-module and in front of each B-module. By this setting a single A-module gets fused to one B-module by recombination.

For the termination of the transcription a terminator goes along with each B-module and gix-site of the A-modules. To determine the starting point of the translation a ribosomal binding site (RBS) is placed between the promoter and the A-modules.

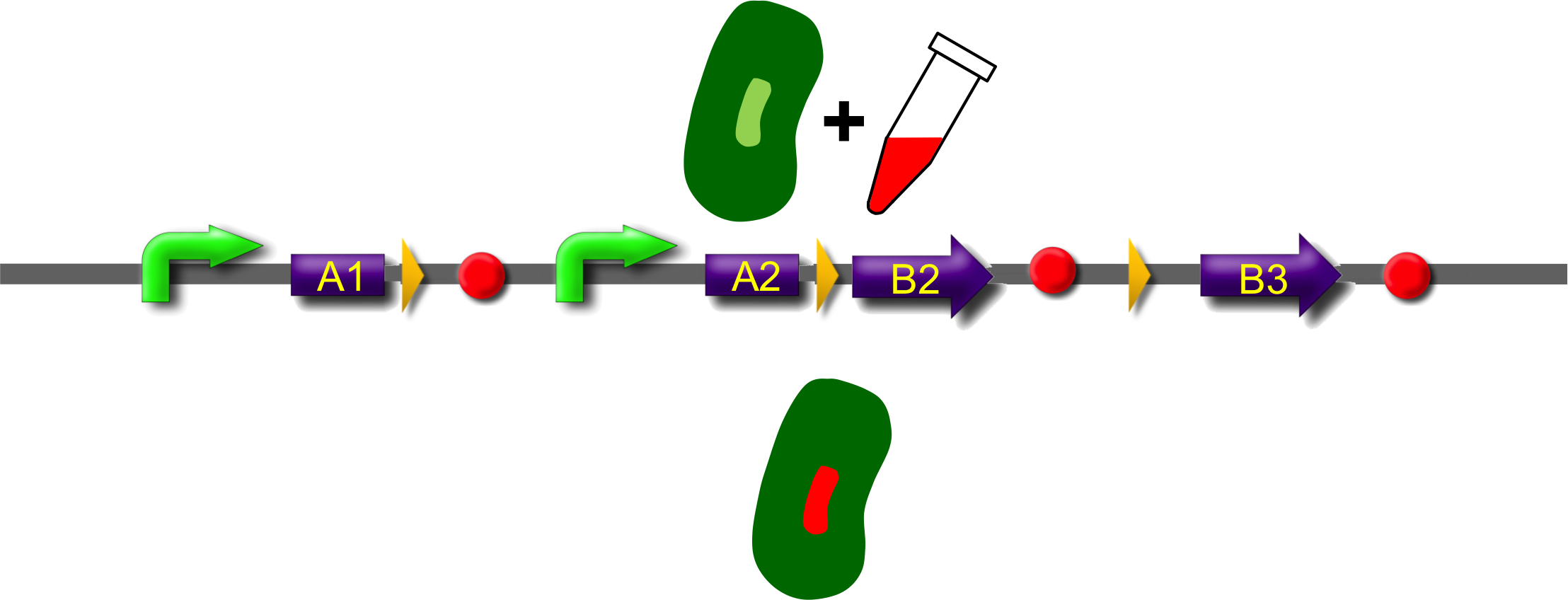

To receive only cells in which recombination of our construct has taken place we used sac b as a suicide gene for selection. Because we wanted to insure that sac b is deleted after recombination it was set downstream of the enhancer. Finally, we made use of an extra plasmid for the Gin-recombinase with an inducible promoter. The assembly of all stated components led to the creation of ˈThe Recombinatorˈ which works like in the following : By inducing Gin, the recombinase can shuffle one A-module to one B-module at the gix-sites randomly. Parts located upstream of the gix-site from the B-module and downstream of the gix-site from the A-module are deleted including the enhancer and sac b. For instance: If A2 is recombinated to B2 then A3, the enhacer, sac b and B1 are removed from the construct and a novel protein A2/B2 arises. This protein is supposed to be found at the cell pole and to fluoresce red. The usage of three A- and B-modules results in nine possible combinations of the modules but can be scaled up by the utilization of further domains. By imitating a kind of evolutional process, which serves in the creation of proteins, there are certain advantages of our system. Modified enzymes can reveal a higher specificity to their substrates or increase their activities by a extended range of substrates. Moreover proteins can acquire improved functions like alternative partners of interaction or a changed stability. Furthermore our system does not depend on rational design that requires the three dimensional structure of the proteins. Besides industrial applications such as the optimization of cellulases, lipases, amylases or the production of synthetic chemicals in novel metabolic pathways the development and improvement of pharmaceuticals and antibiotics attracts the attention. This is due to their causation of side effects and complications which limit their usage. The discovery of potential pharmaceuticals can be overcome by the generation of combinatorial libaries or phage display which can be done by our construct.

All modules are separated by recombination sites that are arranged as direct repeats. Site specific recombination between these sites results in deletion of the intervening sequence (see Box: recombination) and generation of a fusion protein. Each recombination event that is accompanied with deletion of the central region will remove the recombinational enhancer and recombination will stop. Each A-module contains a strong constitutive promoter and a ribosome binding site (RBS) but lack a stop codon. B-modules on the other side lack promoter and RBS but contain a stop codon. As consequence only recombination product between A and B modules is forming a functional fusion construct with a promoter, a ribosome binding site and stop-codon. Non-recombined A-modules may form mRNAs which are rapidly degraded due to the lack of a stop codon. B-modules cannot be transcribed as they lack a promoter.

tmRNA

Because of the upstream localized promoter of the A-modules they can be transcribed in mRNA which is recognized by ribosomes. After the production of a polypeptide the ribosomes are released from the mRNA by a stop codon at the 3ˈ end of the translated mRNA. Due to the fact of missing stop codons in the A-modules the ribosomes are stalled at the mRNA. To rescue stalled ribosomes bacteria own a chimeric RNA molecule called tmRNA (transfer-messenger-RNA). This RNA consists of a tRNAAla at the 3ˈ end followed by ten codons that encode for a tag and a stop codon. The tRNAAla is charged with alanine and binds EF-Tu-GTP. If a ribosome is now stalled by a missing stop codon of the A-module the tmRNA binds to the A site of a ribosome and a transpeptidation takes place. At the end of the tmRNA the stop codon leads to the release of the ribosome. This results in the recycling of the ribosomes and in the degradation of the tagged protein by proteases.

Our suicide gene sacB

To select for cells that contain only recombined A- and B-modules we used the suicide gene sacB for counter-selection. The Bacillus subtilis sacB gene codes for the secreted enzyme levansucrase which belongs to the glycosyltransferase family. The enzyme uses sucrose as substrate to produce the polymer 2,6-beta-D-fructosyl-levan). If levan is present in gram negative bacteria like Escherichia coli it has an lethal effect on the cells. The reason for its toxcity has remained unclear. But there are certain theories about the mechanism. The first one implies that levan encumbers the periplasm because of its high molecular weight. The second one suggests the transfer of fructose residues to inappropriate acceptor molecules that have toxis effects on bacteria cells. For the selection of recombined modules the cells are grown in the presence of sucrose. If the recombination was successful sac b can not be expressed anymore and the cells can grow on succrose sustainable media.

Gay et al. (1985) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC177784/pdf/1781197.pdf

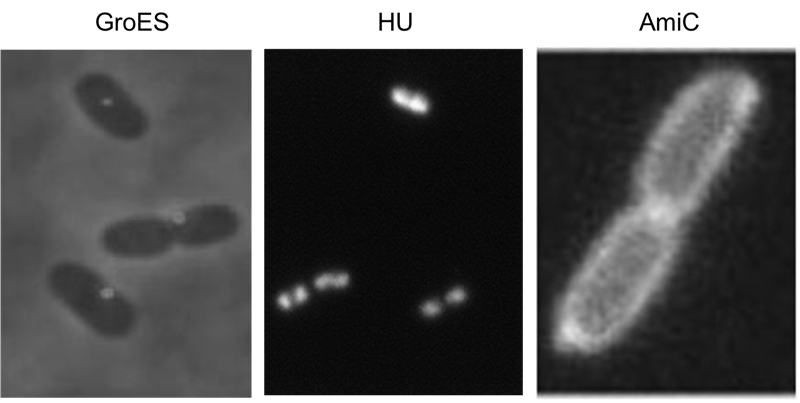

Localization domains

We have screened the literature and identified several bacterial proteins with particular localization within the cell. We decided to use GroES for localization at the cell poles, the small DNA binding protein HU to mark the nucleoid and the amidase AmiC, which is targeted to the periplasm. Depicted are micrographs from the articles by Li et al., 2012, Wery et al., 2001 and Bernhard et al., 2004.

For the examination of a successful recombination we fused a localization domain (A-module) to a fluorescent domain (B-module). However the chosen domains had to comply certain conditions. First of all the domains of the A- and B-modules should possess the ability to yield in a functional protein after their fusion. Moreover the domains had to be distinguishable to demonstrate diverse combinations of the domains. To achieve entirely active proteins we removed any stop codon at the end of the A-modules and tried to avoid their formation at the fusions agency. The applied A-modules should be kept apart due to their localizations inside the cells. So we decided to utilize the domains of HU, GroES and amidase c. HU belongs to a group of ˈhistone-likeˈ small DNA-binding protein and has its function in the organization of the genomic DNA. It is present in Escherichia coli, Eubacteria and homologs of it can be found in several species of bacteria and chloroplasts (Ram et al., 2008; Karcher et al., 2009). So B-modules fused with this domain should be recognized in the area of the nucleoid. Furthermore we used the chaperonin GroES to place fusion proteins at the cell pole. GroES interacts in a complex with GroEL and provides protein folding in the presents of ATP (Li et al., 2012). The third domain was taken from amidase c. Amidase c hydrolyses the cell wall during the cell division and can be localized at the periplasm (Bernhardt et al., 2004). By detection of the generated proteins at different areas of the cell we can ensure that all A-modules are able to fuse with the B-modules.

To assure the same for the B-modules they encode for different fluorescent proteins. In the construct gfp, cfp and mRfp permit guarantee for different combinations of the B-modules with the A-modules.

Fluorescent proteins

[http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/2008/ Nobel prize] Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Outlook

pipapo

References

Bernhardt TG and de Boer PA (2003) The Escherichia coli amidase AmiC is a periplasmic septal ring component exported via the twin-arginine transport pathway.. Mol Microbiol 48:1171-82. ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12787347 pubmed])

Faelen M, Resibois A and Toussaint A (1979) Mini-mu: an insertion element derived from temperate phage mu-1. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 43:1169-77. ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/158471 pubmed])

Gay P, Le Coq D, Steinmetz M, Berkelman T and Kado CI (1985) Positive selection procedure for entrapment of insertion sequence elements in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol 164:918–921. ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2997137 pubmed])

Klippel A, Kanaar R, Kahmann R and Cozzarelli NR (1993) Analysis of strand exchange and DNA binding of enhancer-independent Gin recombinase mutants. EMBO J 12:1047-1057. ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8384550 pubmed])

Li G and Young KD (2012) Isolation and identification of new inner membrane-associated proteins that localize to cell poles in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 84:276–295. ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22380631 pubmed])

Wery M, Woldringh CL and Rouviere-Yaniv J (2001) HU-GFP and DAPI co-localize on the Escherichia coli nucleoid. Biochimie 83:193-200. ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11278069 pubmed])

"

"