Team:MIT/TheKeyReaction

From 2012.igem.org

Introduction

Over the course of the spring, summer, and fall, our team conducted extensive literature searches on molecular probes and DNA computing. This foundation of knowledge has informed our current strategies for achieving RNA strand displacement, which has allowed us to create a test-bed for our designs inside of mammalian cells. We have developed rational design strategies to create orthogonal and protected RNA sequences, and we have been able to deliver our nucleic acid oligomers to mammalian cells. We have also been able to design and test strategies to sense RNAs using strand displacement and create short RNAs in vivo as well as demonstrate NOT logic with strand displacement. These successes have furthermore allowed us to enable the key reaction behind RNA strand displacement in mammalian cells.

Through multiple iterations of each of our two design strategies, we achieved RNA strand displacement in vivo. These results indicate that RNA is capable of acting as a processing medium inside of mammalian cells.

See our page on strand displacement for background information on the mechanism of strand displacement and how one mechanism allows for complex cascading logic circuits before examining our results.

Sneak preview of our data, click to read more:

Design

Principles for designing sequences for the reporting reaction with in vivo strand displacement. The reporting reaction allows us to verify toehold mediated strand displacement, the basis for all sophisticated circuits that we envision.

Iteration 1

The first iteration aimed to replicate existing DNA strand displacement using derived RNA strands.

We used the DNA S6 domain and toehold sequences used by Qian et al. 2011, and converted them into RNA. RNA strand displacement has not yet been published. Furthermore, we added 2'O-methyl modifications to the ribose of each base. This is a widespread RNA modification (e.g. Behlke et al. 2008) that protects the RNA from its own 2'OH, which can catalyze backbone cleavage. It can also protect the strand from enzymatic cleavage by rendering it to a non-substrate for nucleophilic attack.

Regular RNA ribose (left) vs. 2'O-methyl ribose (right). Source: Wikipedia.

Iteration 2

In the second iteration, we optimized our sequences for an in vivo environment.We set out to design new sequences that:

- have increased thermodynamic stability (greater Tm, the melting temperature of a double-stranded complex)

- are orthogonal to RNAs expressed in HEK293 cells

- are more protected from nuclease activity

- are more protected from the RISC complex

We achieved this by:

- increasing the domain and toehold lengths

- increasing the G/C content

- analyzing the HEK293 transcriptome

- researching literature for protective modifications

Sequence Selection Algorithm

We analyzed HEK293 transcriptome data by fetching the accession IDs from HEK293 Cell Database and then the corresponding sequences from GenBank. Duplicate sequences were removed.

We first chose an 8 nucleotide (nt) toehold sequence. The sequence space was restricted to a 3-base code (A/T/C) with the sequence ending in 5' CA 3' clamp (see Qian et al. above). We calculated the Hamming distance between each potential toehold and the transcriptome, along with the number of exact consecutive nucleotide matches from the beginning to rank each potential sequence. The resulting list can be sorted by deviation from the mean for each possible Hamming distance (0-8) and exact consecutive run (0-8). The best sequence would be one for which low Hamming distance instances are relatively (>=1 standard deviation) less common and high Hamming distances are relatively more common. Similarly, shorter consecutive run instances are more favored over longer ones.

5' UACUAC CA 3' // has repeats

Top 5 generated toeholds.

5' ACUAUC CA 3' // choose this one

5' CCUAUA CA 3'

5' CUAUAC CA 3'

5' ACCUAU CA 3'

Then, the same approach was used to identify the 20 nt domain sequence. However, generating all sequences is very time intensive with roughly 320 combinations of 3-base code sequence to evaluate. Instead, a genetic algorithm was used to generate sequences, evaluate them and to improve on the top scoring sequences by mutating them or performing crossovers with other sequences. After an overnight run of four threads of this algorithm, the best sequences were selected. Then the sequence with the highest G/C content and fewest repeats was chosen. In principle, the latter constraints can be added to the automatic scoring feature of the genetic algorithm.

Protective Base Modifications

The original strands were modified with 2'O-Methyl groups on the ribose sugar (see above). We kept these modifications on the newly designed strands.

For strands without 3' fluorophore (ROX or Alexa 488) modifications, we added a phosphate group to the 3' end. According to IDT, this protects from some 3' exonuclease degradation. Input strands received an IR800 modification on the 5' end for quantification and potential protection from 5' exonucleases.

Protective Sequence Modifications

To protect against the RISC complex, we made a variant of the reporter top strand that included a bulge 10 nucleotides from the 3' end (Iba et al., 2012). There were 3 different bulges published by Iba et al., but only one of them, 5' CACU 3', used a 3-base code, so we chose this sequence as the bulge.

Nucleic Acid Delivery

In order to implement the key reaction of RNA strand displacement in vivo, we first demonstrated our ability to deliver nucleic acids to mammalian cells through a variety of methods and reagents. In this section, we will review three different nucleic acid delivery techniques to mammalian cells: (1) Delivery of plasmid DNA, (2) Delivery of 2'-O-Methyl RNA and (3) Delivery of plasmids with inducible protein control.

1. Delivery of Plasmid DNA to Mammalian Cells

Through the Gateway method, we have assembled many promoter-gene constructs as detailed on our Biobrick Parts Page. After construction of the plasmid, we delivered the plasmid DNA to HEK293 (Human Embryonic Kidney) cells through transient transfection. In particular, we used lipofection with Lipofectamine 2000 reagent. See Materials and Methods for our Gateway and lipofection protocols.

This figure shows HEK293 cells which were transiently transfected with Hef1A:TagBFP and Hef1A:mKate using Lipofectamine 2000. Equimole amounts of DNA were delivered, 500 ng total per 1.65 uL of reagent. Images were taken on a Zeiss microscope at 10X. (a) Brightfield (b) Overlay of blue, red and brightfield (c) Blue channel (d) Red channel

2. Delivery of 2'-O-Methyl RNA to Mammalian Cells

The movie above shows HEK293 cells expressing constitutive eYFP which are transfected with a 2'-O-Methyl RNA strand labeled with ROX (5-carboxy-x-rhodamine) on the 3' end. As time passes, the complex/vesicles are uptaken by the cell, releasing their payload and resulting in whole cell fluorescence. Each frame is 5 minutes, movie encompasses 200 minutes in 9 seconds.

Time point images taken at T = 0, 2, 3, and 4 hours post-transfection. Images taken at 10X on Zeiss microscope.

Time point images taken at T = 0, 2, 3, and 4 hours post-transfection. Images taken at 10X on Zeiss microscope.

Spontaneous dissociation and rapid degradation of RNA oligomers often occur under in vivo conditions. Our experiments to demonstrate strand displacement require that our RNA be stable and react predictably in cells. Thus, we chose to use chemically-modified 2'O-methyl RNA, a naturally occurring and nontoxic RNA variant found in mammalian ribosomal RNAs and transfer RNAs. The -OH functional group at the 2' position on each nucleotide is replaced with an -O-Me group, which prevents cleavage of the RNA backbone. In addition to a significant increase in stability against nucleases, the modification seems to confer increased melting temperature. This minimizes the probability that the RNA strands will dissociate upon introduction to the cellular environment.1. Because 2'O-methyl RNA exhibits different chemistry than normal RNA, we developed specific protocols to deliver these constructs to mammalian cells.

Figure 1

We then ran optimization experiments to optimize the ratio of 2'-O-Me RNA delivered to RNAiMAX (transfection reagent used) to achieve maximum transfection efficiency. The invitrogen protocol2 for Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent recommends 0.6 to 30 pmol of nucleic acid delivered per well per 24-well plate. Throughout our experiments we observed that we could see high transfection efficiency for 30 pmol of RNA but almost no transfection for 15 pmol, so we ran a titration experiment, (Figure 1), testing out 20, 25 and 30 pmol of RNA with 1.0, 1.33 and 1.5 uL of transfection reagent and see saturation levels at 25 pmol. Therefore, the rest of our experiments were standardized around 25 pmol of RNA delivered with 1.33 uL of reagent:

Figure 1 shows a normalized graph of flow cytometry data with the FITC channel on the x-axis showing arbitrary fluorescence units and cell count on the y-axis, normalized. We can see that as we move from 0 to 20 to 25 picomoles of double stranded RNA delivered, the entire cell population shifts toward higher fluorescence levels, but we start to saturate the system as we see fluorescent population shift left at 30 picomole of RNA delivered.

3. Inducible Control of Protein Expression

In this circuit, a constitutive mammalian promoter, Hef1A, drives expression of a trans-activator, rtTA3. rtTA3 activates the Tre-Tight promoter in the prescence of doxycycline (DOX), a small molecule. Tre-Tight drives expression of mKate, a red fluorescent protein. In addition, a plasmid containing the Hef1A promoter driving expression of TagBFP, a blue fluorescent protein, is used as a transfection marker.

In this circuit, a constitutive mammalian promoter, Hef1A, drives expression of a trans-activator, rtTA3. rtTA3 activates the Tre-Tight promoter in the prescence of doxycycline (DOX), a small molecule. Tre-Tight drives expression of mKate, a red fluorescent protein. In addition, a plasmid containing the Hef1A promoter driving expression of TagBFP, a blue fluorescent protein, is used as a transfection marker.

To move from transfecting RNA into cells to transcribing RNA in vivo, we needed to control the expression of RNA, whether mRNA or short non-coding RNAs used in strand-displacement circuits. We achieved this by demonstrating the use of inducible expression systems.

To characterize these systems, we constructed a system where an inducible promoter drives the expression of a fluorescent protein, which allows for quantification of the protein expression levels. Protein expression in turn informs us of mRNA levels.

In this system, we have constitutive expression of rtTA3 driven by the Hef1A promoter. In the presence of doxycycline (DOX), rtTA3 can activate the Tre-Tight (TreT) promoter, which is driving expression of mKate, a red fluorescent protein.

100,000 HEK293 cells were transfected with equimolar rations of Hef1a:rTTA3, TreT:mKate, and Hef1a:TagBFP (as a transfection marker), standardized to 500 ng total plasmid DNA, with 1.65 uL Lipofectamine 2000. After 48 hours, cells were imaged on a Leica Confocal Microscope at 10x. We can see that we have transfection, since cells are fluorescing blue. Also, we can see that as we increase the concentration of DOX present, we see an increase in red fluorescence.

100,000 HEK293 cells were transfected with equimolar rations of Hef1a:rTTA3, TreT:mKate, and Hef1a:TagBFP (as a transfection marker), standardized to 500 ng total plasmid DNA, with 1.65 uL Lipofectamine 2000. After 24 hours, DOX was then added to 16 different concentrations ranging from 0.1 nM to 5000 nM. Lastly, cells were harvested for flow cytometry after 48 hrs and allowed to count 10,000 events. As we increase concentrations of DOX, the mean red fluorescence increases.

Experimental RNA Strand Displacement

Through multiple iterations of each of our two design strategies, we achieved RNA strand displacement in vivo. These results indicate that RNA is capable of acting as a processing medium inside of mammalian cells.

Click hereto see our initial data with our first design:

Click here to skip to our best data where we demonstrate strand displacement

Design One

In vitro

To inform our in vivo work and enable the key reaction of strand displacement, we verified our designs in vitro (see Protocol). Even though the sequences used were from previously published work, strand displacement reactions with RNA inputs to RNA reporters or other gate:output complexes have not been published in vitro, so we needed to establish that RNA works as the substrate for toehold-mediated strand displacement.

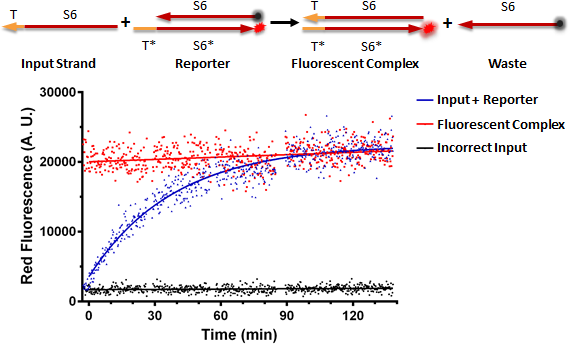

Testing an RNA reporter in vitro. The negative control received a scrambled input, whereas the positive control only contained the fluorescent complex. The experimental well contained the reaction shown at the top of the figure, where the toehold T of the input strand binds the complementary toehold T* on the reporter complex, which is non-fluorescent due to the presence of a quencher near the fluorophore. This results in the initiation of branch migration, which results in a fluorescent complex, and a waste molecule (free quencher strand).

Conclusion: RNA can be used as a processing medium in vitro.

In vivo

Our first strategy to implement the key reaction of RNA strand displacement in vivo was to adapt the DNA sequences of inputs, gates and reporters from the Qian/Winfree, "Scaling Up Digital Circuit Computation with DNA Strand Displacement Cascades," 2011 Science Paper to 2’-O-Methyl RNA strands, which we successfully tested in vitro and now to transfect with Lipofectamine 2000 into mammalian cells.

Experimental Design: HEK293 (Human Embryonic Kidney) cells were used that constitutively express a yellow fluorescent protein (eYFP) in order to be easily visible in microscopy images. For RNA transfection protocols, please visit our Methods page. The negative control well did not receive any RNA. The positive control well received a gate strand tagged with a ROX fluorophore annealed to an input strand, to act as a product of a strand displacement reaction. The scrambled input well received the reporter and an input strand containing the correct toehold domain but the incorrect binding domain. In the correct input well, the cells received the double stranded reporter as well as an input strand with the correct toehold domain and hybridization domain.

Images taken at 15.5 hours post transfection on a Zeiss microscope at 10X.

Results: We should expect that the toehold of the input strand binds to the complementary exposed toehold on the double stranded reporter, and will branch migrate and effectively kick off the output strand of the reporter that is tagged with a quencher. Therefore, the fluorophore will no longer be quenched, yielding red fluorescence. We see from the above figure that in the negative control well, 200,000 HEK293+eYFP cells are healthy and adherent. In the positive control well, we see localized red fluorescence in the form of vesicles as well as distributed, whole cell red fluorescence. In the scrambled input well, we see red vesicles as well as red whole cell fluorescence. In the correct input well, we see only whole cell red fluorescence.

Conclusion: The quenched reporter comes apart in the vesicles and possibly inside of the cells, too.

Iteration Two of Design One: Switch Transfection reagent to RNAiMAX

From the first foundational experiment, we observed localized red fluorescence in vesicles as well as whole cell fluorescence. This indicates that our reporter complex is either melting, being degraded or being recognized by a specific enzyme, as well as the reporter is coming apart inside of the lipofectamine vesicles. We researched better transfection reagents for double stranded RNA, and found that Lipofectamine RNAiMAX is designed specifically for the delivery of double stranded RNA, whereas Lipofectamine 2000 is specifically designed for the delivery of plasmids.

Once we received the new transfection reagent, we set up experiments similar to the initial experiment but with an optimized protocol for RNAiMAX (See Methods).

These images were taken on a Zeiss microscope at 10x at 15.5 hours post-transfection in the red channel. Negative control received only double stranded quenched ROX complex (Reporter) with an exposed toehold. Correct Input received the reporter and an input with the correct toehold and binding domain to strand displace the top strand of the reporter.

Conclusion: From collected data, we observed that RNAiMAX is a superior reagent for double stranded RNA, and we now only see the reporter coming apart inside of cells instead of inside vesicles. However, the experimental well and the negative control exhibit the same behavior still, which leads us to Iteration Three, where we observe what is going wrong in our system.

Iteration Three of Design One: Tag RNA strand with an Alexa Fluorophore to act as a transfection marker

Since we continually observed a trend of the reporting strand coming apart inside of the cell (i.e. the quencher no longer quenching the fluorophore) we modified the reporter with an additional fluorophore, AlexaFluor488 to act as a transfection marker, so that we could observe the reporter entering the cell. AlexaFluor488 is a green dye, and we predict that if the two strands melt inside of HEK293 cells then we would see an initially green vesicle enter the cell and then localized green and red fluorescence in the cytoplasm, indicating that the strands came apart.

This is a graph of flow cytometry data with FITC on the x-axis in arbitrary fluorescent units and texas-red on the y-axis. We can see that the no transfection well serves as our negative control. The dsROX is our positive control and acts as the product of a strand displacement reaction. The No input well received the new reporter tagged with AlexaFluor488 and generally stays annealed inside of the cell as we see the population lie mainly along the FITC axis. The blue population received the new tagged reporter with the correct input, which should yield a strand displacement reaction, and we do see that the population lies between the no input population and the positive control, indicating that we do see some strand displacement.

Conclusion: AlexaFluor488 acts as a troubleshooting mechanism, so that we can see the reporter has been transfected inside of the HEK293 cells and the efficiency is high. There appears to be some strand displacement activity, but we decided to redesign the reporter to optimize the key strand displacement reaction.

Design Two

In vitro

To verify that the modifications we made in the second iteration of our strand design (see above) do not interfere with strand displacement, we tested them in vitro.

Testing the second iteration of an RNA reporter in vitro. Compared are the strands without bulge (left) and with the protective bulge (right). Kinetics and completion levels are nearly identical between the two variants, suggesting that the bulge does not interfere with strand displacement.

Conclusion: The 2nd set of de novo designs work for strand displacement and the bulge does not significantly affect the toehold-mediated strand-displacement reaction.

In Vivo

Back to results overviewWe demonstrated the key reaction of RNA strand displacement in vivo using both the techniques of nucleofection and transfection. Our best data from design iteration two is below:

Nucleofection Data:

This is flow cytometry data, taken 15 minutes post-nucleofection, with FITC (green channel) on the x-axis in arbitrary units and Texas-Red on the y-axis in arbitrary units. The No Transfection population is the negative control of 200,00 HEK293 cells. The dsROX population was nucleofected with 10 pmol of a double stranded tagged ROX complex (the product of a strand displacement reaction) to act as a positive control for strand displacement. The No Input (green population) received 10 pmol of the long, new designed reporter, which we can see is shifted far right on the FITC axis, demonstrating high transfection efficiency. When we nucleofect 33 pmol of the correct input with 10 pmol of the reporter (the blue population), we see the population shift up, exhibiting green and red fluorescence, indicating that strand displacement occurred.

This is a graph of flow cytometry data from the same experiment above showing Texas Red in A.U. on the x-axis and cell count on the y-axis. We can quantitatively see an entire population shift (6-fold) in the experimental well of cells that receive the correct input and the reporter versus the well that receives only the reporter.

This graph shows a 200-point moving average of the data from the nucleofection experiment above. The red line, dsROX, is a positive control that acts as the product of a strand displacement reaction. The green line, no input, shows cells that were nucleofected with only the reporter, and we see that for higher levels of green fluorescence (indicating higher nucleofection efficiency), red levels stay low (indicating no strand displacement). The blue line, input, shows cells that were nucleofected with the reporter and the correct input, and we see that higher levels of green correspond to higher levels of red fluorescence (indicating strand displacement occurred).

Nucleofection Experiment Results: This experiment has shown that we can demonstrate RNA strand displacement in vivo using the reporting mechanism after reformulating a new design for our sequences and testing multiple iterations of the design. This experiment was performed following the Lonza protocol to nucleofect HEK293 cells. According to this protocol (but at 4C to better protect the double strand from melting), we delivered the controls and correct inputs and reporters to the cells. The concentration of the reporter was 500nM whereas the input was 1.5uM. In the above figure, it is clear that the cells that received reporter and input (blue line) have a higher red fluorescence than the cells that received only the reporter (green line).

Transfection Data:

This graph shows flow cytometry data with FITC on the x-axis in A.U. and Texas-Red on the y-axis. A 200-point moving average was taken to reduce noise in the data. We can see that for higher levels of green fluorescence (indicating transfection efficiency) in the FITC channel, the no input well and scrambled input wells have consistent low levels of red fluorescence (indicating no strand displacement). However, for the input well, higher levels of green fluorescence correlate with higher levels of red fluorescence, which indicates that for higher transfection efficiency of our reporter, we see more strand displacement taking place.

Experimental Design and Results: This foundational experiment has finally shown that we can demonstrate RNA strand displacement in vivo after reformulating a new design for our sequences and testing multiple iterations of the design. In this experiment, each well received 150,000 HEK293 cells in supplemented DMEM. For controls, No Transfection is a well which only received cells. The No Input well was transfected with 25 pmol of our new designed longer reporter using RNAiMAX reagent. The experimental well labeled Scrambled Input, was transfected with 25 pmol of both the reporter and an input strand with the correct toehold but incorrect binding domain, which would not yield a strand displacement reaction. The experimental well labeled Input, was transfected with 25 pmol of both the reporter and the input strand with the correct toehold and binding domain, which can bind to the exposed toehold of the reporter and through branch migration, knock off the top strand of the reporter, yielding an unquenched fluorophore and successful strand displacement reaction In Vivo.

"

"