Team:Calgary/Notebook/Hydrocarbon

From 2012.igem.org

Week 1 (May 1-4)

Week 2 (May 7-11)

Decarboxylation

For the decarboxylation sub-project, the second week was entirely focused on literature research and the practice of basic laboratory techniques. 8 potential pathways were identified as potential candidates for naphthenic acid decarboxylation. The first of these would utilize only the University of Washington's "PetroBrick" (from iGEM 2011), consisting of the genes encoding the enzymes acyl-ACP reductase (AAR) and aldehyde decarbonylase (ADC). We have planned to verify the PetroBrick in the distribution plates and test its efficacy on naphthenic acids in the coming weeks. If this proves to be unsuccessful, we will begin investigating the alternative approaches, beginning with replacing AAR with carboxylic acid reductase (CAR) from Nocardia iowensis, a very unspecific reductase shown to work on structures resembling naphthenic acids. Failing this, the remaining pathways will be examined; however, the disadvantage in these pathways is their direct reliance on the success of the other steps, as the naphthenic acids must be degraded to the point of resembling branched-chain fatty acids (since all remaining pathways are related to fatty acid metabolism).

Denitrification

In the first two weeks of iGEM our group has focused on reviewing literature regarding the bioremediation of nitrogen groups attached to naphthenic acids. The most prevalent N heterocycle is carbazole, representing 75% of total nitrogen by mass. The upper pathway of carbazole biodegradation is catalyzed by the enzymes coded for by the car operon, CarA (CarAaAbAd), CarB (CarBaBb), and CarC. These enzymes convert carbazole to anthralinic acid. The lower pathway is catalyzed by the enzymes of the ant operon, antA, B, and C, yielding cathecol while releasing CO2 and NH3. The car and ant operons are both regulated by the Pant regulator which is induced by the protein, antR. CarAa also has its own promoter which is not induced by antR. We have also investigated an alternative pathway using CarA combined with an amidase (amdA) that selectively cleaves NH2 from an intermediate of the car pathway. This could bypass much of the car/ant pathway and is possibly more efficient.

We have decided to use Pseudomonas resinovorans and Rhodococcus erythropolis to amplify these genes from. CarABC and AntABC from P. resinovorans has been shown to have a wide range of nitrogen containing substrate specificity. R. erythropolis contains the amdA gene that we wish to use, and some evidence suggests that it may also be able to degrade sulfur rings through its CarABC pathway.

In addition to our research we have also been learning some of the lab techniques we will be using this summer. This includes transforming a plasmid into E. coli, plating and selecting for bacteria containing the plasmid, verifying with colony PCR, performing a mini-prep and a restriction digest.

Desulfurization

Alongside the wider team involved in the naphthenic acids to hydrocarbon development aspects of the project, this week was dedicated to familiarising ourselves on the protocols that will be available to our disposal. Specifically, we explored rudimentary tools needed in an investigation of microbial biology such as polyremase chain reaction, gel verification, preparation of overnight cultures, as well as developing a procedural flowchart to transform competent cells with registry biobricks. With regards to our sub-group specific goals, we reviewed the current available literature around various industrial and laboratory approaches to desulfurization of organic groups, especially in the petroleum industry. This included a side-along comparison of non-biological processes such as conventional hydrodesulfurisation that is currently employed in petroleum product refinery stages and how biological routes would supplement and perhaps even offer several advantages over these methods. Current limitations to biological desulfurisation, however, includes such factors as biocatalyst stability, enzyme specificity, desulfurization rate, and a need for a carbon source to regenerate co-factors. We also identified the enzyme desulfinase operating as one of the bottlenecks in the desulfurisation pathway. Overall, our goals moving forward involve determining the specific pathways involved in the desulfurization process, as well as the reaction conditions we would want to employ and identifying specific model compounds, in addition to dibenzothiophene (DBT) that we could use to test the effectivity of our biosystem in order to determine its functionality in the conversion of NAs to economically valuable hydrocarbons.

Ring Cleavage

This week we mainly researched aromatic ring cleaving using intra- and extradiol dioxygenases from species of Pseudomonas and Bacillus but also began literature searches on aliphatic ring cleavage done by monooxygenases.

Week 3 (May 14-18)

Decarboxylation

The third week included some additional literature investigation in the first two days. The iGEM distributions arrived this week, and verification began on May 17th by transformation into E. coli, followed by colony PCR on May 18th (using standard protocols on the wiki). Additionally, primers were designed for CAR in N. iowensis, along with primers for Nocardia posphopantetheine transferase (NPT), a second enzyme required for optimal function in the former, and a short list of contacts were acquired to request the donation of the required strain (called NRRL 5646) from researchers who have worked with it previously. A sort of form email was drafted for this purpose, and should this be unsuccessful, we will be purchasing the strain from DSMZ (http://www.dsmz.de). In the following week, we will begin with development of overnight cultures and gel preparation.

Ring Cleavage

In the second week we continued to do more research on the degradation of alicyclic compounds and found two strains of bacteria that contained genes needed for this process. The first strain, Thauera butanivorans, contains the genes required to activate the ring by adding a hydroxyl group. The gene is called butane monooxygenase and is composed of three subunits, a hydroxylase, a reductase, and a regulatory component. The second strain, Acinetobacter sp. SE19, contains the genes needed to oxidize the alcohol, formed by butane monooxygenase, and to cleave the ring. There is a cluster of nine genes that perform this oxidation and cleavage but only six are involved directly.

Desulfurization

Building on the previous week's literature review, the 4S pathway was recognised as the preferred biological mechanism that we would explore in devising a desulfurisation biosystem. Of specific interest is the dsz operon as well as DszD which is a FMN:NADH reductase, an essential component of the pathway, but not part of the operon. ''Rhodococcus erythropolis IGTS8'' was the preferred model in investigations of the pathway. An alternative to the DszD, HpaC, was also recognised as a viable option. Following this, other protocols added to our growing lab methods 'toolkit' were a restriction digest protocol, PCR purification, and finally, DNA construction digest. Aims moving forward include obtaining strains of the R. erythropolis, while also executing a timeline devised to biobrick, test, and incorporate the genes necessary in the above processes in a biobrick circuit.

Week 4 (May 22-25)

Decarboxylation

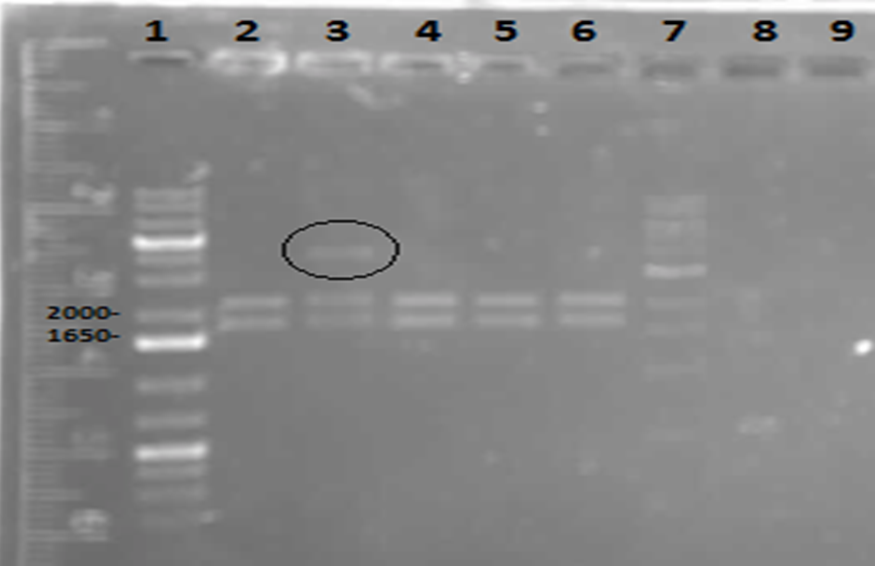

This week, a gel was prepared for the colony PCR prepared last week, and the gel was run, yielding results that were very difficult to see. The PCR and gel electrophoresis process were repeated, yielding the following gel:

[[File:UCalgary_igem_PCRverfication_Hydrocarbon_PetroBrick_Gel_1.PNG|thumb|500px|center]]Results indicate successful transformation with the PetroBrick. Lane 1 contains the 1 kb plus ladder, while Lanes 2-11 contain the results of colony PCR. Each of these bands correspond to the PetroBrick vector, which is 2070bp, indicating that the transformation was successful. Lane 12 contains a positive control, which varies distinctly from the colony PCR results. The negative control lane is empty as expected.

Overnight cultures were grown from the colonies were prepared this week. Sigma compounds - for the purpose of testing the PetroBrick on naphthenic acid analogues - were selected from the list provided. The compounds to be used include cyclohexanepentanoic acid, cycohexane-1,1-dicarboxylic acid, and benzo[b]thiophene-3-acetic acid. A mini-prep was completed on the overnight cultures prepared earlier in the week, according to protocol obtained from the wiki. The DNA concentration in the resulting samples was measured by nanodrop to confirm successful plasmid extraction, and the resulting DNA concentrations were as follows:

- Tube 1: 44.9 ng/mL

- Tube 2: 54.2 ng/mL

- Tube 3: 54.4 ng/mL

- Tube 4: 41.6 ng/mL

- Tube 5: 34.3 ng/mL

Because tube 3 (prepared from Colony 3, Plate 3) had the highest concentration, it was to be used for the eventual sequencing of the plasmid. The restriction digest was completed also, but it was not run on a gel this week; this was left for Week 5.

Contents |

Desulfurization

This week was kicked off with a project development meeting with Emily and David, and we devised a protocol for biobricking the hpaC. Additionally, methods to place the genes coding for the 4 enzymes, DszA,B,C and HpaC into a single construct were explored. Within the lab, the PCR performed on the resuspended pUC18-hpaC was not successful initially. Furthermore, we ordered the substrates/compounds that we are going to use. Once the substrates and the Rhodococcus strain arrive we are going to test how effectively the bacteria can desulfurize different sulphur-containing compounds that resemble NAs. Finally, Dr. Yoshikazu Izumi involved in the team that developed an improved efficiency dszB through directed mutagenesis in 2007 was contacted to request the plasmid that contains the mutation. dszB is a major bottleneck in the 4S pathway and if a strain or sample containing this mutation was obtained, it would significantly bolster our later testing efforts on DBT, as well as other compounds such as thiophane.

Denitrification

<p>This week we reviewed the primers listed in the database and also designed some new ones. Primers for CarAa, CarAc, and CarAd were designed individually, while primers for CarBaBbC and AntABC were designed to encompass multiple genes in a sequence. These primers were designed to be used on Pseudomonas putida which we decided to use as our gene source since it was available to us as opposed to ordering Pseudomonas resinovorans. We also designed a primer for the AmdA gene from Rhodococcus erthyroplois. In addition to ordering these primers we also ordered the nitrogen containing compounds that we will need to test these enzymes on. We decided on using carbazole to make sure the enzymes can perform their natural function as well as pyrrolidine to test them on a similar ring structure. We also ordered cyclohexamine in order to independently test the function of the alternative AmdA pathway. Finally, we decided to eventually order 4-Piperidine butyric acid hydrochloride to test how the enzymes will work on nitrogen containing naphthenic acids. However, we decided since it is a very expensive compound we would wait to make sure the enzyme's work on more simple compounds before ordering it.We also started our work in the wet lab by plating colonies and making an overnight culture of -80 freezer stock Psuedomonas putida on Thursday. We also resuspended the primers for CarAa, CarAc, CarAd, AntA, AntB, and Ant C that were already in the database. We were able to use the colonies that grew on the streak plates to start a colony PCR to attempt to isolate each of these genes on Friday.

Ring Cleavage

We started looking into more organisms that can carry out cyclohexane degradation and found one called Brachymonas petroleovorans. This organism is capable of both hydroxylating cyclohexane and carrying out cyclohexanol oxidation. We are also hoping to find evidence that Pseudomonas fluorescens, Pf-5 has genes that can cleave aliphatic rings, however, first we have to determine if Pf-5 can grow in the presence of butylcyclohexane. To do so we carried out an assay, using LB, testing the toxicity of butylcyclohexane on Pf-5. After 24 hours of incubation we took OD600 readings¬ which suggested that the presence of butylcyclohexane did not have effect on cell growth. We also looked up Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5 in the Pseudomonas Genome Database and found genes that code for proteins with similar functions to what we have found for aromatic and aliphatic ring cleavage.

Bioinformatics/Modelling

Handy bioinformatics tools

FMM (From Metabolite to Metabolite) is a critical tool for synthetic biology. FMM can reconstruct metabolic pathways form one metabolite to the other one. <a href:http://fmm.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/>http://fmm.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/</a>

This webpage runs the software that performs the enumeration of all pathways for target compounds in KEGG. More precisely, the desired KEGG compound is submitted in order to get the map of all pathways connecting the compound to metabolites endogenous to E. coli. Optionally, the full map containing the supplements can also be requested. <a href:http://bioretrosynth.issb.genopole.fr/tools/metahype/>http://bioretrosynth.issb.genopole.fr/tools/metahype/</a>

DNA Designer 2.0 is a Drag and drop standalone software, runs on Windos, MacOS. <a href:https://www.dna20.com/secure/order.php?page=genedesigner2>https://www.dna20.com/secure/order.php?page=genedesigner2 </a>

DNADesign is a Web-based application <a href:http://genedesign.thruhere.net/gd/> http://genedesign.thruhere.net/gd/</a>

Modelling

Constraint-based flux analysis - modeling microorganism metabolic network and perform flux analysis.

The metabolic network is translated in to a matrix and then the simulation will calculate a pathway that optimizes the goal (max biomass or max production).

The network will be reconstructed (gene/reaction can be added or deleted) to enhance the expected pathway to degrade target compounds. The media (compounds, thermo-conditions) will be manipulated to find the best condition(s) that satisfy the microorganisms to digest the target compounds and reach a good growth rate (say above threshold).

Week 5 (May 28 - June 1)

Decarboxylation

On Tuesday (May 29), a gel was run on the restriction digests of the extracted plasmids from Week 4, which appeared to confirm the successful transformation of the PetroBrick, showing clear bands at the pertinent locations. The gel is as follows:

Lane 1 contained the 1 kb plus ladder, while lanes 2-6 contained the restriction digest results, which had used the five different miniprep tubes with plasmids isolated from five different colonies. As can be observed in the gel, the upper row of bands corresponds to 2392bp, indicating the petrobrick part. The lower set of bands corresponds to the PetroBrick pSB1C3 vector at 2070 bp. These results suggest that the PetroBrick plasmid had been successfully purified.

Based on the apparent success of the gel, the products were sent away for sequencing. Long-term stocks were prepared for the alkane production medium outlined in University of Washington's PetroBrick protocols from 2011 (see https://2011.igem.org/Team:Washington/alkanebiosynthesis). These stocks are as follows:

- 1 L of 1M Tris (pH = 7.25)

- 10 mL of 1 mg/mL Thiamine

- 10 mL of 10% Triton x-100

- 1 M MgSO4

- 0.1 M FeCl3 (anhydrous)

The medium itself is to be prepared in Week 6 once the results of sequencing are (hopefully) acquired.

Ring Cleavage

This week we redid the previous assay with Pf-5 and butylcyclohexane using glass vials instead of falcon tubes. These vials allowed for more surface and better containment of the volatile compound. We carried out this assay using both LB and M9-MM. After 24 hours we took OD600 readings and obtained similar results as last week. The growth was considerably decreased in the M9-MM, however we are not sure whether the bacteria were able to use the compound as a carbon source because the MM contained glucose. The fact that the growth decreased showed that they might depend on the glucose in the media to grow.

Denitrification

On Monday and Tuesday we used the database primers to attempt to isolate CarAa, CarAc, CarAd, AntA, AntB, and AntC from the Psuedomonas putida we plated last week. CarAd, AntB, and AntC were all put in the gradient PCR machine to account for the wide range of their primers’ melting points, while the others were done via regular PCR. Unfortunately, no positive results were obtained from these reactions. The PCR on CarAc and AntA was repeated on Wednesday, still not giving positive results. Finally, we attempted to use a salt concentration gradient on the PCR reaction for CarAc and AntA, using concentrations that ranged from 1.0 microlitres/tube to 2.0 microlitres/tube in increments of 0.2 microlitres/tube. This helped as CarAc showed bands in samples that had concentrations of 1.2 and 1.4 microlitres/tube. AntA also showed bands, however they were not the correct size, indicating contamination and/or non-specific annealing of the primer. The positive control also showed bands of the correct size. Earlier in the week we also made overnight cultures of 3 environmental strains (28, 29, 30) of Psuedomonas putida from -80 glycerol stock. On Friday we performed a genomic prep on these cultures, and plan on attempting to amplify genes from the isolated DNA next week.

Desulfurization

Since we wanted to make sure we would not run out of pUC18(plasmid containing hpaC gene), we transformed some E.coli cells with it. We grew them on plates containing A, K, T and C antibiotics and they only grew on A. Therefore pUC18 has A resistance. We did a three sets of PCR with hpaC primers, one using 1/10 dilution of pUC18, the other using 1/100 dilution of pUC18 and one with the colonies we had just obtained by transforming the E.coli cells with pUC18. The PCR worked and we saw bands of the same size for all three sets of PCR. (Unfortunately, the picture we saved is not a good one since some of the bands faded awayunder UV). Then we did a PCR purification to obtain the pure hpaC gene. We also did 3 sets of digestion(using pairs of X&P enzymes, E&S enzymes and E&P enzymes) to insert the hpaC gene into the pSB1c3 vector. All the sets grew successfully. Following the above successes with hpaC, the arrival of our rhodococcus strain afforded us the opportunity to begin investigation of the dsz operon using the primers current in our reagent library. The gram-positive nature of the strain also dictated we explore various lysing strategies before the Dsz genes could be amplified for further purification and biobrick construction steps (as with the hpaC). PCR was carried out using dszA primers on three different treatments {microwave, lysate buffer, and a control} which yielded banding pattern around 1200 base pairs for the lysate treatment (2%SDS and 10% tritonX-100, plus heat for 5mins at 98C).

Week 6 (June 4 - June 8)

Decarboxylation

This week, we first made a streak plate of our confirmed Petrobrick E.coli Colony 3, Plate 2, as well as a long-term glycerol stock for storage. In accordance with the Washington team’s protocols, we prepared our M9 minGlucose Media (Production Media) with the following reagents:

- 75mL ddH2O

- 0.6g Na2HPO4

- 0.3g KH2PO4

- 0.05g NaCl (855.6mL 1M solution)

- 0.2g NH4Cl

- 20mL of 1M Tris (pH = 7.25)

- 1mL of 10% Triton

- 100mL of 1mg/mL thiamine hydrochloride

- 10mL of FeCl3 (anhydrous)

- 100mL of MgSO4

**3.0g glucose needed to be added later after the mixture was autoclaved, as glucose is known to caramelize under the conditions of the autoclave.

We also prepared an overnight stock containing 5mL of LB broth inoculated with E.coli from our verified colony. The following day we measured its optical density, demonstrating that our OD was 1.311, suitable for our purposes. We obtained our PetroBrick sequencing results with a complementarity of 87%, as compared to the theoretical PetroBrick in the PartsRegistry, which was deemed by iGEM team leaders to be high enough to continue in our protocol. We also performed glucose filtration, transferring 3g of glucose into our Production Media solution after it had been autoclaved in order to ensure sterile transfer. On the final day of the week, we were able to start our General Production Protocol that would be followed by a 48 hour incubation. It was in this time that hydrocarbon production was reportedly supposed to occur. Use of the GC would occur in the following week to test for alkane production.

Denitrification

We started off this week by determining the DNA concentration of our genomic prep samples from last week using the nanodrop. DNA concentration for all three putida strains was at least 1000 ng/microlitre, well above what was needed for PCR. 1/2 and 1/3 dilutions were prepared for all three strains so as not to have an excess of template DNA in PCR reactions. PCR was performed on all 3 strains using primers for CarAc, CarAd, AntA, AntB, and AntC using 6 replicates per gene. The only successful amplification appeared to be AntB and CarAc, both from strain 28 (with weaker bands in strain 29). We then performed another PCR, just on those two genes with an increased amount of Taq polymerase to hopefully get enough amplified DNA to move forward with. This resulted in strong bands for both at the expected size. We then performed PCR purification using the Qiaquick kit and obtained samples containing 33.5 ng/microlitre of AntB DNA and 129 ng/microlitre of CarAc DNA. These concentrations were both sufficient to begin a restriction digest and ligation of these parts into vector PSB1C3. Next week we hope to verify the results of the restriction digest, continue to amplify CarAc and AntB from strain 28, and hopefully submit a biobrick for sequencing.

Desulfurizationtion

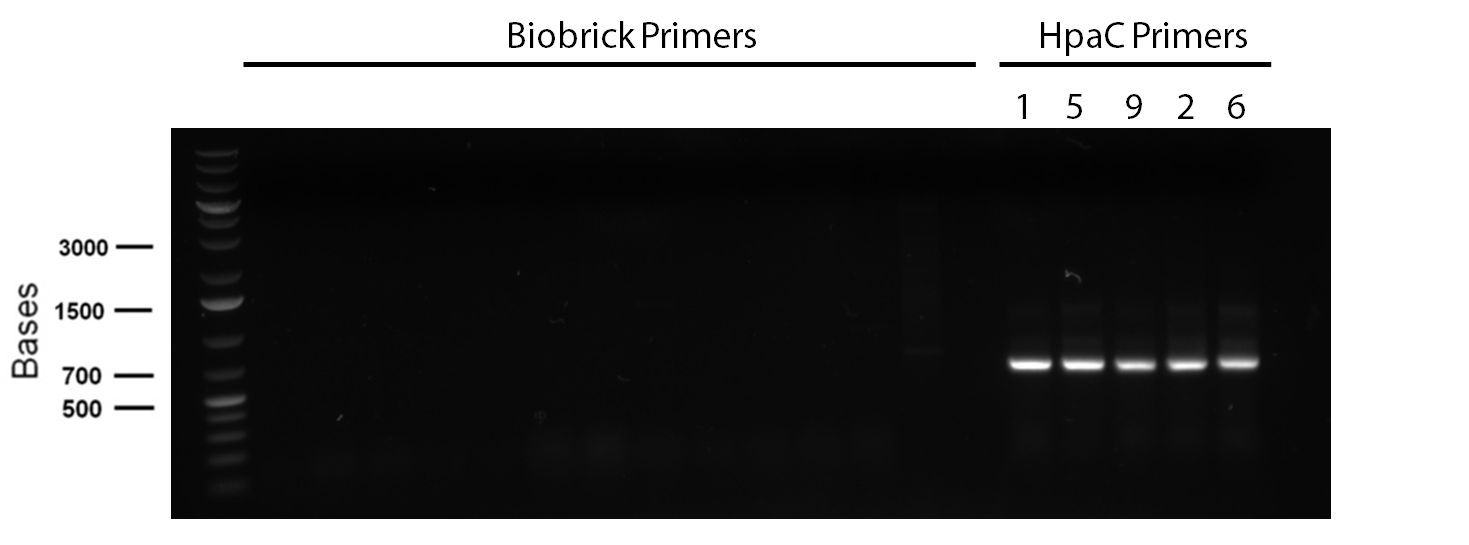

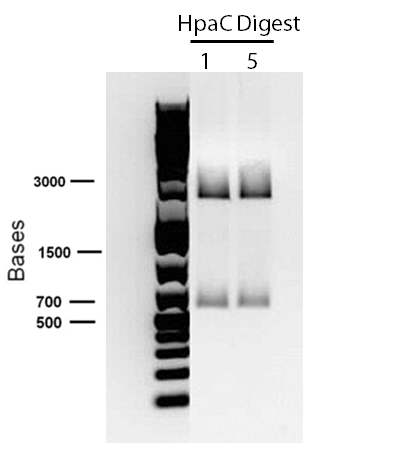

</p> In order to confirm the hpaC biobrick construction, first we did two sets of colony PCR(choosing white colonies from the 3 plates we grew last week). One with hpaC primers and one with biobrick primers. After running them on the gel(first picture below) we saw equal bands for the PCRs performed using hpaC bands(However, a PCR using biobrick primers was performed later and the same results were obtained). Colonies 1(-) and 5(-) were used to make overnight cultures with. Then the overnight cultures were used for miniprep. Digestions were performed on the miniprep products using EcoRI and Pst. The results were good(second picture below) and two bands were observed on each column (one for vector and the other for hpaC). hpaC was sent in for sequencing. </p>

</html>

PCR reagents were prepared to re-test/confirm previous results of dszA amplification following two different lysing treatments (microwave + lysate buffer). This time, all three genes were amplified and gel verification showed clear banding patterns around 500bp range for all three genes for the microwave treatment. Remaining PCR products were run on a gel and extracted for further purification steps; however, presence of any genetic material were not confirmed through nanodropping which raised concerns about the composition of the purified products or the success of the initial amplification step, or perhaps even the lysis treatment. Further experimentation will have to be carried out to troubleshoot.

Week 7 (June 11 - June 15)

Decarboxylation

After preparing our production media 48 hour incubation sample for gas chromatography and extracting with ethyl acetate, we left our sample for use in the GC. Our results indicated a small hydrocarbon peak, indicating a possibility that hydrocarbon production had been a success, but it was not distinct enough to make this conclusion. The procedure would be repeated, this time creating sigma compound solutions as well. These sigma compounds would resemble naphthenic acids. In order to ensure that hydrocarbon peaks would be produced from these compounds and not from glucose, we prepared a new production media lacking glucose, in hopes that incubated bacteria could survive for long enough without a food source to decarboxylate a sigma compound to some extent. Since the sigma compounds we initially selected for our purposes had not arrived as of yet, we opted for others: Cyclohexanepentanoic acid (CHPA), cyclohexanecarboxylic acid, and 1,4-cyclohexanedicarboxylic acid. We performed 8 overnight cultures and prepared sigma compound solutions. Despite our many attempts, we were only able to acquire an OD of about 0.6 for these 8 tubes. We then performed our production protocol with the tubes, preparing them with the following reagents and inoculating them with the contents of our broth cultures:

- Tube 1: Glucose

- Tube 2: Glucose

- Tube 3: Glucose and CHPA

- Tube 4: Non-glucose and CHPA

- Tube 5: Glucose and cyclohexanecarboxylic acid

- Tube 6: Non-glucose and cyclohexanecarboxylic acid

- Tube 7: Glucose and 1,4-cyclohexanedicarboxylic acid

- Tube 8: Non-glucose and 1,4-cyclohexanedicarboxylic acid

In the above tubes, “glucose” indicated that glucose-containing production media was used, whereas “non-glucose” indicated that the production media lacking glucose was used. In each case where a sigma compound was added, it was present at a concentration of 25mg/L. Each production tube was then left for a 48 hour incubation over the weekend, to perform gas chromatography tests the following week.

Denitrification

The purified PCR products for CarAc and AntB were digested with restriction enzymes EcoRI+SpeI, EcoRI+PstI, and XbaI+PstI. However, only PSB1C3 plasmids that had been digested with EcoRI+SpeI and EcoRI+PstI were available to attempt ligation. Gel results were inconclusive on the restriction digest product as the plasmid size appeared much larger than expected. However, transformation was still attempted on the ligation products for both genes (both using EcoRI+SpeI ligation into PSB1C3 plasmid). The transformation products were plated onto chloro plates to select for colonies that had the chloro resistance gene on the PSB1C3 plasmid. Also this week another round of PCR was performed for the Car and Ant genes, however all, but CarAc showed bands in the negative control lane, possibly indicating contamination or the formation of primer dimers. The CarAc bands were fairly weak and a PCR purification resulted in very low DNA concentration, insufficient to move onto restriction digest. Next week's plan hinges heavily on the result of the transformation from this Friday.

Desulfurisation

This week, we took a two-pronged approach in our lab experimentation with one focusing on amplifying dsz genes and purifying them (then finally constructing biobricks), and also a side focus on developing a plasmid purification protocol for the PSB1C3-hpaC and pUC18-hpaC plasmids to replenish our current stocks. For the dsz aspect, we were able to successfully grow extra plates of rhodococcus strain which was used to inoculate PCR tubes. Gel verification, however, afforded a very contradictory result with significant streaking and false positives with similar banding pattern to previous gels run in the previous week. A final gel verification of a random sample of a tube of PCR products from dszA,B,C respectively and two negative control treatments involving master mix only and the lysed cells only illustrated the lack of discrepancy between the supposed successful amplification and the lysed cells (with lysate buffer) alone. This results recommended we take a different approach involving plasmid isolation carried out before PCR, rather than applying the PCR reagents directly to a hypothetically lysed culture sample. On the bright side, PSB1C3-hpaC verification through sequencing was successful, confirming the construction of our first biobrick (out of the four). Subsequently, O/N cultures of the plasmid containing cultures were prepared and stored in glycerol at -80C. Furthermore, verification of catalase gene part (BBa_K137068) from the parts registry was initiated, with our newly identified biobricked-hpaC acting as a positive control, but the banding pattern was not very conclusive.

Week 8 (June 18 - June 22)

Denitrification

The results of our transformation on CarAc and AntB from last week showed mostly red colonies indicating that the ligation was unsuccessful and that the PSB1C3 plasmid simply closed on itself with no insert. However, there were three colonies for CarAc that were white (cut with both X+P and E+P). Colony PCR was performed on these three colonies using biobrick primer sets to verify that the part had been inserted in these colonies, but unfortunately all PCR results were negative indicating an unsuccessful ligation.

We also performed a miniprep on Psudomonas putida strain #28 this week using a home-made protocol rather than the Qiagen kit. Miniprep A had a DNA concentration of 1539.8 ng/uL and Miniprep B had DNA concentration of 1001.2 ng/uL possibly indicating that there may have been a lot of genomic DNA contamination. However miniprep A product was still used as a PCR template for a reaction attempting to isolate CarAc, CarAd, AntA, AntB, and AntC. Special conditions for this PCR included replacing 60 uL of water with 60 uL of betaine heated to 37 degrees Celsius and running a Mg gradient ranging from 0.5 uL - 2.5 uL per tube for each gene. Of these only AntB had bands of the right size in 3 of the lanes (Mg concentrations of 1.5, 2, and 2.5 uL). However, all of the AntB bands (including the negative control) contained a contamination band at around 100 bases, probably due to the formation of primer dimers. This forced us to do a gel extraction rather than a PCR purification. This gel extraction did not work as the nanodrop results indicated high amounts of agarose contamination. Another PCR was performed using the same conditions, but using miniprep B instead as there was no more miniprep A product remaining. Unfortunately there were no bands for AntB, only the 100 basepair contamination bands.

"

"