Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Results/Summary

From 2012.igem.org

Summary

Datapage

How our system works

Data for our favorite new parts

- <partinfo>K863000</partinfo> - bpul (laccase from Bacillus pumilus) with T7 promoter, RBS and HIS tag:

- <partinfo>K863005</partinfo> - ecol (laccase from E. coli) with T7 promoter, RBS and HIS tag:

Data for pre-existing parts

We have also characterized the following parts

- <partinfo>BBa_K863012</partinfo> - tthl laccase ( from T. thermophilus) with constitutive promoter J23100, RBS and HIS tag:

- <partinfo>BBa_K863022</partinfo> - bhal laccase (from Bacillus halodurans) with constitutive promoter J23100, RBS and HIS tag:

Laccase from Bacillus pumilus DSM 27 (ATCC7061)

First some trails of shaking flask cultivations were made with different parameters to define the best conditions for the production of the His-tagged BPUL. Because of no activity in the cell lysate a purification method was established (using Ni-NTA-Histag resin). The purified BPUL could be detected by SDS-PAGE (molecular weight of 58,6 kDa) as well as MALDI-TOF. To improve the purification strategies the length of the elution gradient was increased. The fractionated samples were also tested concerning their activity. A maximal activity of X was reached. After measuring activity of BPUL a scale up was made up to 3 L and also up to 6 L.

Shaking Flask Cultivation

The first trails to produce the BPUL were produced in shaking flask with various designs (from 100 mL-1 to 1 L flasks, with and without baffles) and under different conditions. The parameters we have changed during our screening experiments were the temperature (27 °C,30 °C and 37 °C), different concentrations of chloramphenicol (20 to 170 µg mL-1), various induction strategies (autoinduction and manual induction), several cultivation times (6 - 24 h) and in absence or presence of 0,25 mM Cu2Cl. Due to the screening experiments we identified the best conditions for expression of BPUL:

- flask design: shaking flask without baffles

- medium: autoinduction medium

- antibiotics: 60 µg mL-1 chloramphenicol

- temperature: 37 °C

- cultivation time: 12 h

The reproducibility and repeatability of the measured data and results were investigated for the shaking flask and bioreactor cultivation with n≤3.

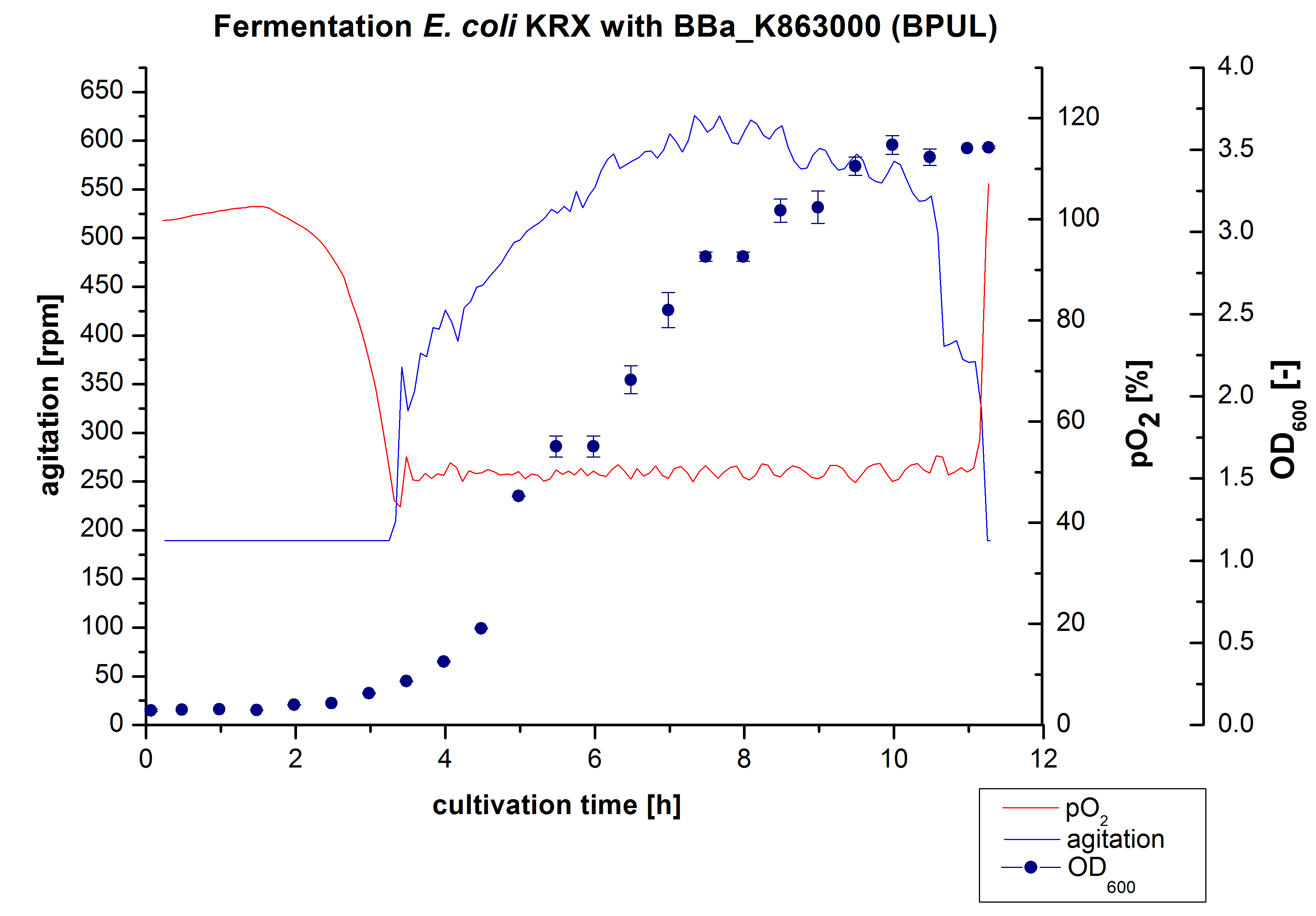

3 L Fermentation E. coli KRX with <partinfo>BBa_K863000</partinfo>

After the measurement of activity of BPUL we made a scale-up and fermented E. coli KRX with <partinfo>BBa_K863000</partinfo> in Braun Biostat B with a total volume of 3 L. Agitation speed, pO2 and OD600 were determined and illustrated in Figure 1. We got a long lag phase of 2 hours due to a relativly old preculture. The cell growth caused a decrease in pO2 and after 3 hours the value fell below 50 %, so that the agitation speed increased automatically. After 8,5 hours the deceleration phase started and therefore the agitation speed was decreased. There is no visible break in cell growth through induction of protein expression. It is probably that we did not produce such a great amount of BPUL that it had any influence on cell growth or that it is not active so far. The maximal OD600 of 3,53 was reached after 10 hours, which means a decrease of 28 % in comparison to the fermentation of E. coli KRX under the same conditions (OD600,max =4,86 after 8,5 hours, time shift due to long lag phase). The cells were harvested after 11 hours.

Purification of BPUL

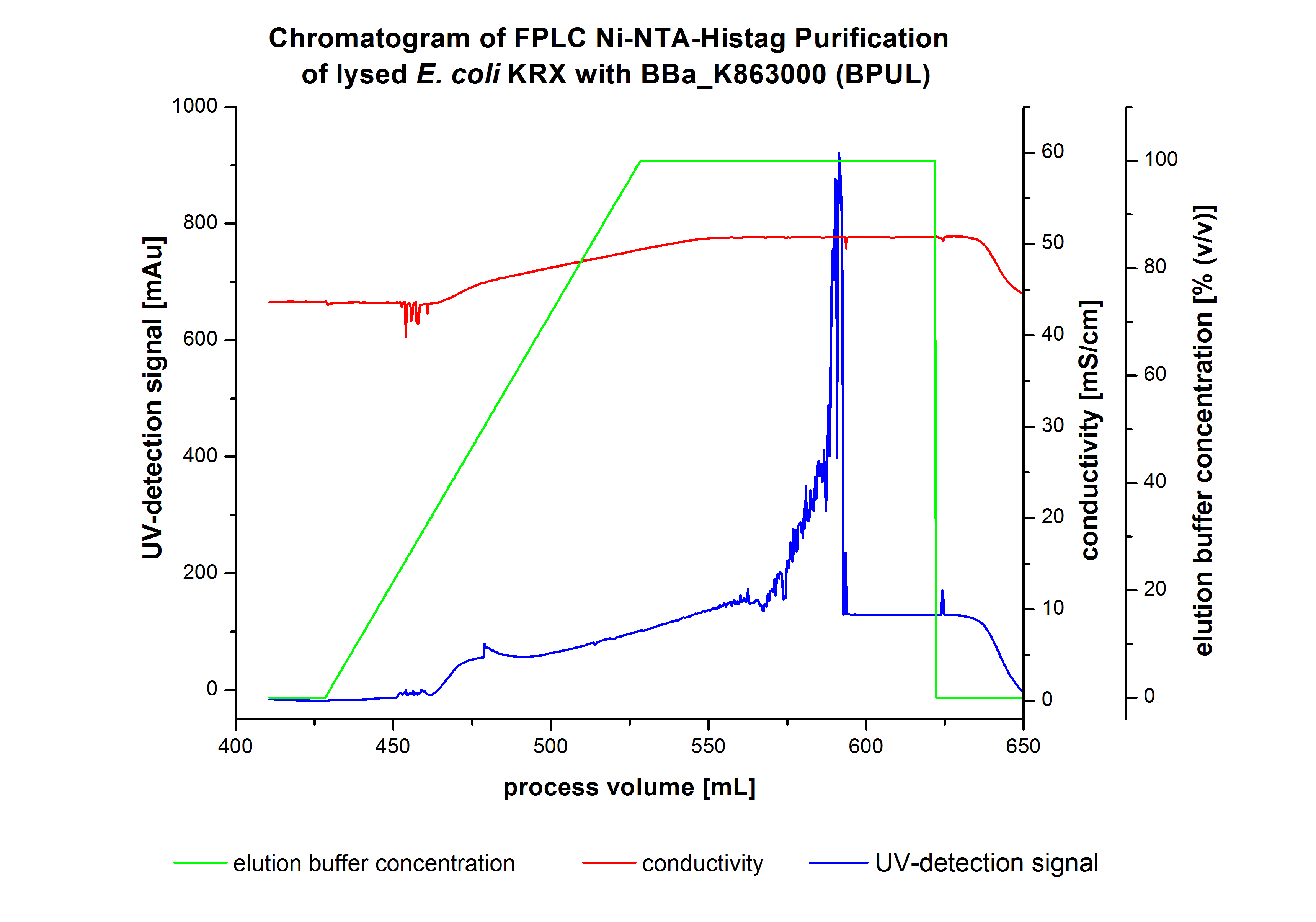

The harvested cells were resuspended in Ni-NTA-equilibrationbuffer, mechanically lysed by homogenization and centrifuged. The supernatant of the lysed cell paste was loaded on the Ni-NTA-column (15 mL Ni-NTA resin) with a flowrate of 1 mL min-1 cm-2. Then the column was washed by 10 column volumes (CV) with Ni-NTA-equilibrationbuffer. The bound proteins were eluted by an increasing Ni-NTA-elutionbuffer gradient from 0 % to 100 % with a total volume of 100 mL and the elution was collected in 10 mL fractions. The chromatogram of the BPUL-elution is shown in figure 2:

The chromatogram shows a remarkable widespread peak between the process volume of 460 mL to 480 mL with the highest UV-detection signal of 69 mAU , which can be explained by the elution of bound proteins. The corresponding fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE analysis. Afterwards the UV-signal increased caused by the changing imidazol concentration during the elution gradient. Between the process volume of 550 and 580 mL there are several peaks (up to a UV-detection-signal of 980 mAU) detectable. These results are caused by an accidental detachment in front of the UV-detector. Just to be on the safe side, the corresponding fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE analysis. The results of the SDS-PAGE are shown in the following pictures.

SDS-PAGES of purified BPUL

Figure 3 shows the purified culture of E. coli KRX with <partinfo>BBa_K863000</partinfo> lysates (fermented in 3 L Braun Biostat B). For this SDS-PAGE two of three samples were treated before. The cell disrupting buffer was exchanged to MilliQ, because of its usability for the activity test. It shows the elution fractions 1 and 2 before and after the buffer exchange and elution fraction 3 only before buffer exchange. The arrow marks the BPUL band with a molecular weight of 58,6 kDa. This PAGES shows, that BPUL could be expressed and eluted (first 2 fractions) successfully and that the exchange of buffers leads to a loss of the amount of proteins.

The appearing bands were analysed by MALDI-TOF and could be identified as CotA (BPUL).

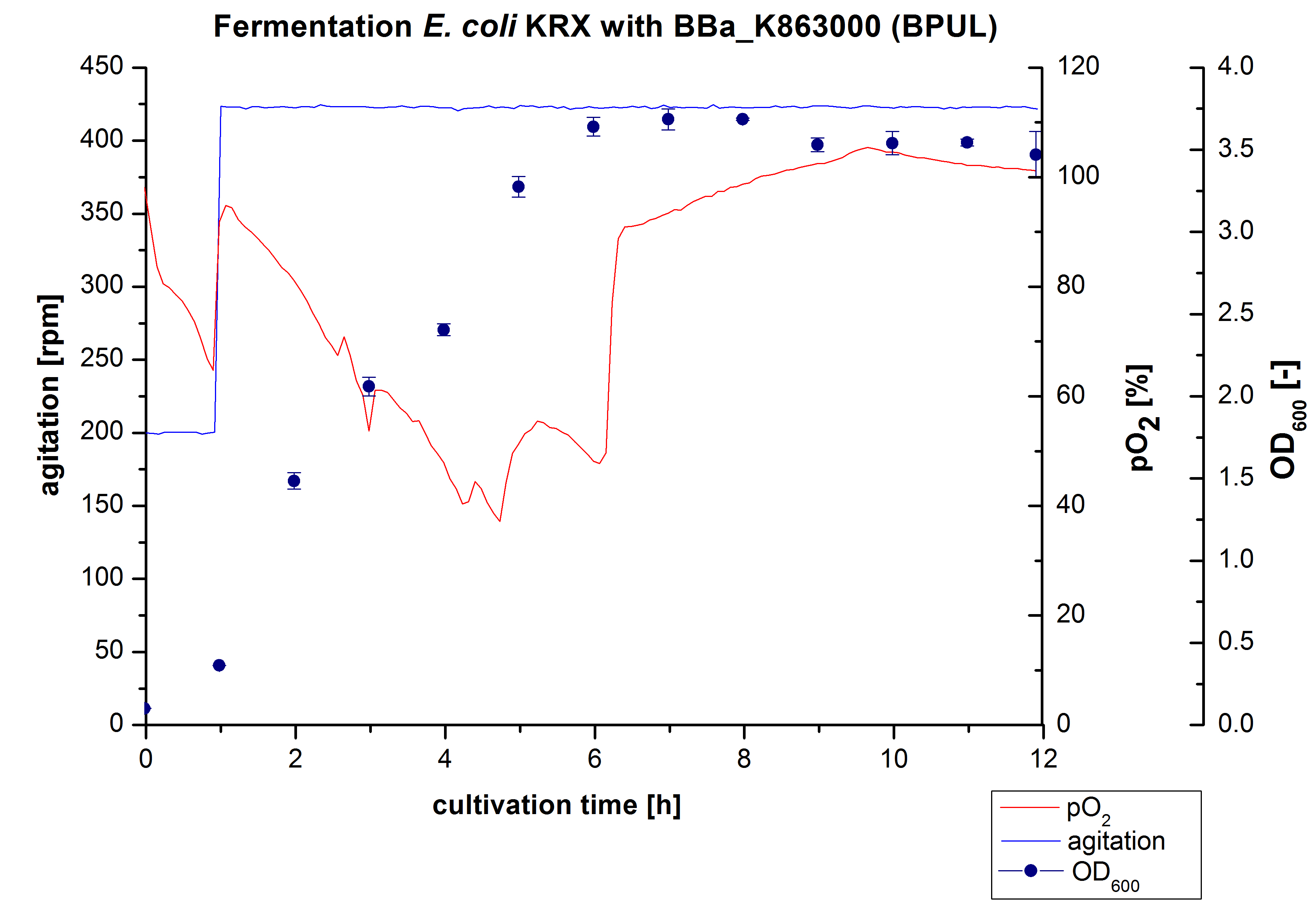

6 L Fermentation of E. coli KRX with <partinfo>BBa_K863000</partinfo>

Another scale-up of the fermentation of E. coli KRX with <partinfo>BBa_K863000</partinfo> was made up to a final working volume of 6 L in Bioengineering NFL22. Agitation speed, pO2 and OD600 were determined and illustrated in Figure 3. There was no noticeable lag phase. Agitation speed was increased up to 425 rpm after one hour due to problems caused by the control panel. The pO2 decreased until a cultivation time of 4,75 hours. The increasing pO2-Level indicates the beginning of the deceleration phase. There is no visible break in cell growth caused by an induction of protein expression. A maximal OD600 of 3,68 was reached after 8 hours of cultivation, which is similar to the 3 L fermentation (OD600 = 3,58 after 10 hours, time shift due to long lag phase). The cells were harvested after 12 hours.

Purification of BPUL

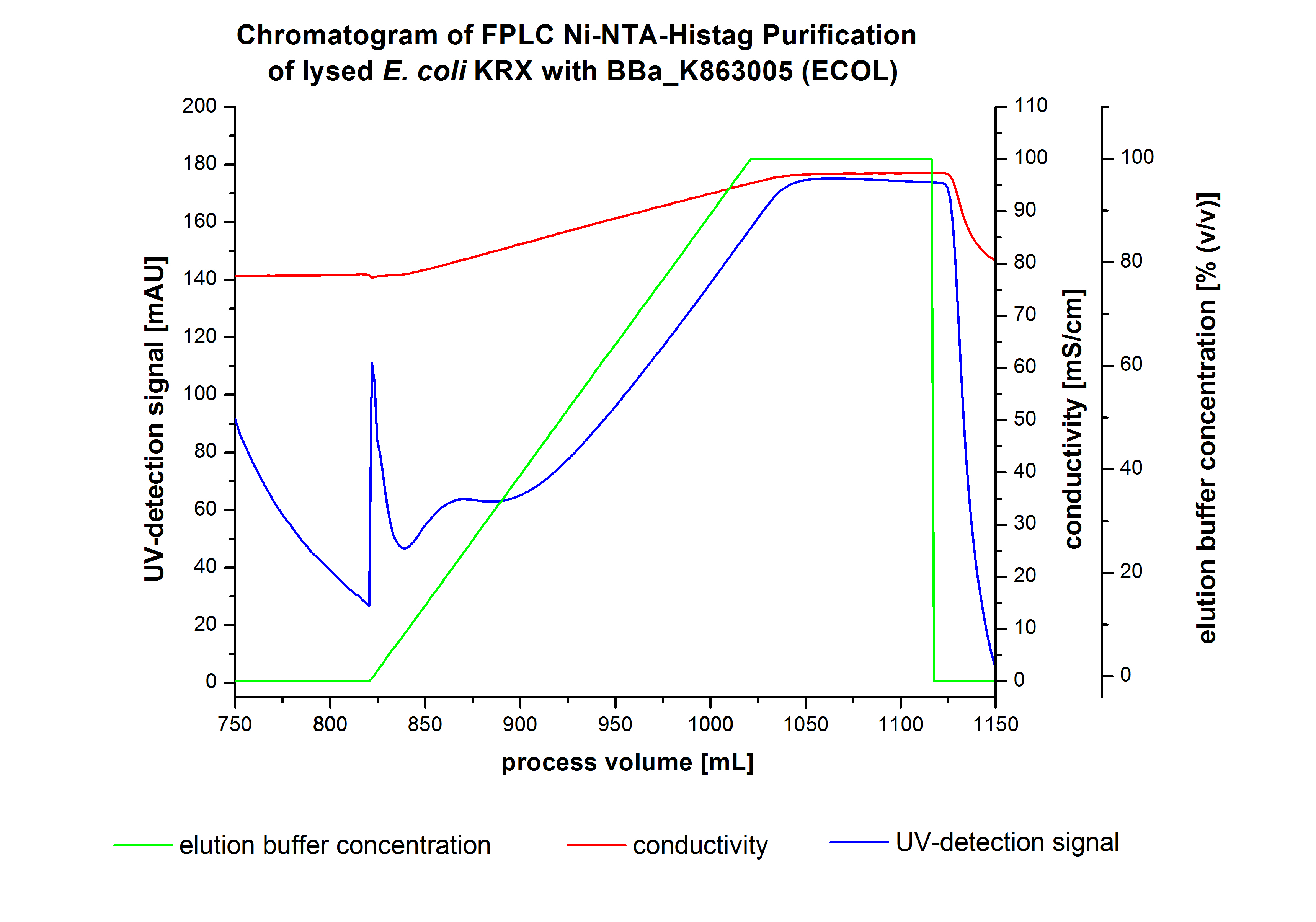

The harvested cells were prepared in Ni-NTA-equilibrationbuffer, mechanically lysed by homogenization and centrifuged. The supernatant of the lysed cell paste was loaded on the Ni-NTA-column (15 mL Ni-NTA resin) with a flowrate of 1 mL min-1 cm-2. The column was washed by 5 column volumes (CV) with Ni-NTA-equilibrationbuffer. The bound proteins were eluted by an increasing elutionbuffer gradient from 0 % (equates to 20 mM imidazol) to 100 % (equates to 500 mM imidazol) with a total volume of 200 mL. This strategy was chosen to improve of purification by a slower increase of Ni-NTA-elutionbuffer concentration. The elution was collected in 10 mL fractions. The chromatogram of the BPUL-elution is shown in figure 5.

The chromatogram shows a peak at the beginning of the elution. This can be explained by pressure fluctuations upon starting the elution procedure. Between a process volume of 832 mL and 900 mL there is remarkable widespread peak with a UV-detection signal of 115 mAU. This peak corresponds to an elution of bound proteins at a Ni-NTA-elutionbuffer concentration between 10 % and 20 % (equates to 50-100 mM imidazol) . The corresponding fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE analysis. The ensuing upwards trend of the UV-signal is caused by the increasing imidazol concentration during the elution gradient. Towards the end of the elution procedure there is a constant UV-detection signal, which shows, that the most of the bound proteins was already eluted. Just to be on the safe side, all fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE analysis to detect BPUL. The results of the SDS-PAGE are shown in the following pictures.

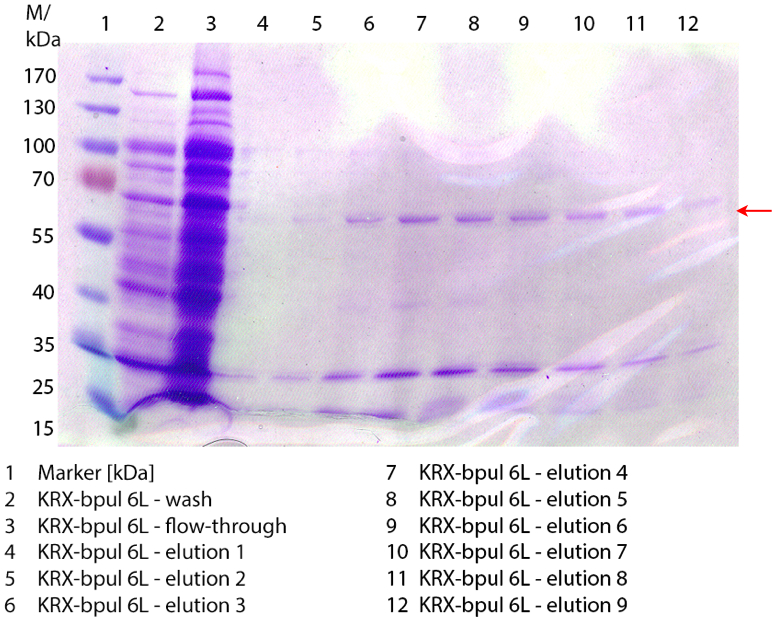

SDS-PAGES of purified BPUL

In figure 6 the SDS-PAGE of the Ni-NTA-Histag purification of the lysed culture of E. coli KRX containing <partinfo>BBa_K863000</partinfo> is illustrated. It shows the flow-through, wash and elution fractions 1-9. BPUL has a molecular weight of 58,6 kDA and was marked with a red arrow. The band appears in all fractions from 2 to 9 with a variing strength, with the strongest ones in fractions 7 to 9. There are also some other non-specific bands, which could not be identified. Therefore the purification method has to be improved for the next time.

Furthermore the bands were analysed by MALDI-TOF and identified as CotA (BPUL).

Laccase from Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3)

First some trails of shaking flask cultivations were made with changing parameters to identify the best conditions for the production of the laccase ECOL fused to a Histag. Because of no activity in the cell lysate a purification method was established (using Ni-NTA-Histag resin). The purified ECOL could be identified by SDS-PAGE (molecular weight of 53,4 kDa) as well as MALDI-TOF. The fractionated samples were also tested concerning their activity. A maximal activity of X was reached. After measuring activity of ECOL a scale up was made up to 3 L and then also up to 6 L.

Shaking Flask Cultivations

The first trails to produce ECOL were produced in shaking flask with various designs (from 100 mL-1 to 1 L flasks, with and without baffles) and under different conditions. The parameters we have changed during our screening experiments were the temperature (27 °C,30 °C and 37 °C), different concentrations of chloramphenicol (20-170 µg mL-1), various induction strategies ([autoinduction autoinduction and manual induction), several cultivation times (6 - 24 h) and in absence or presence of 0,25 mM Cu2Cl. Due to the screening experiments we identified the best conditions under which ECOL was expressed:

- flask design: shaking flask without baffles

- medium: autoinduction medium

- antibiotics: 60 µg mL-1 chloramphenicol

- temperature: 37 °C

- cultivation time: 12 h

The reproducibility and repeatability of the measured data and results were investigated for the shaking flask and bioreactor cultivation with n ≤ 3.

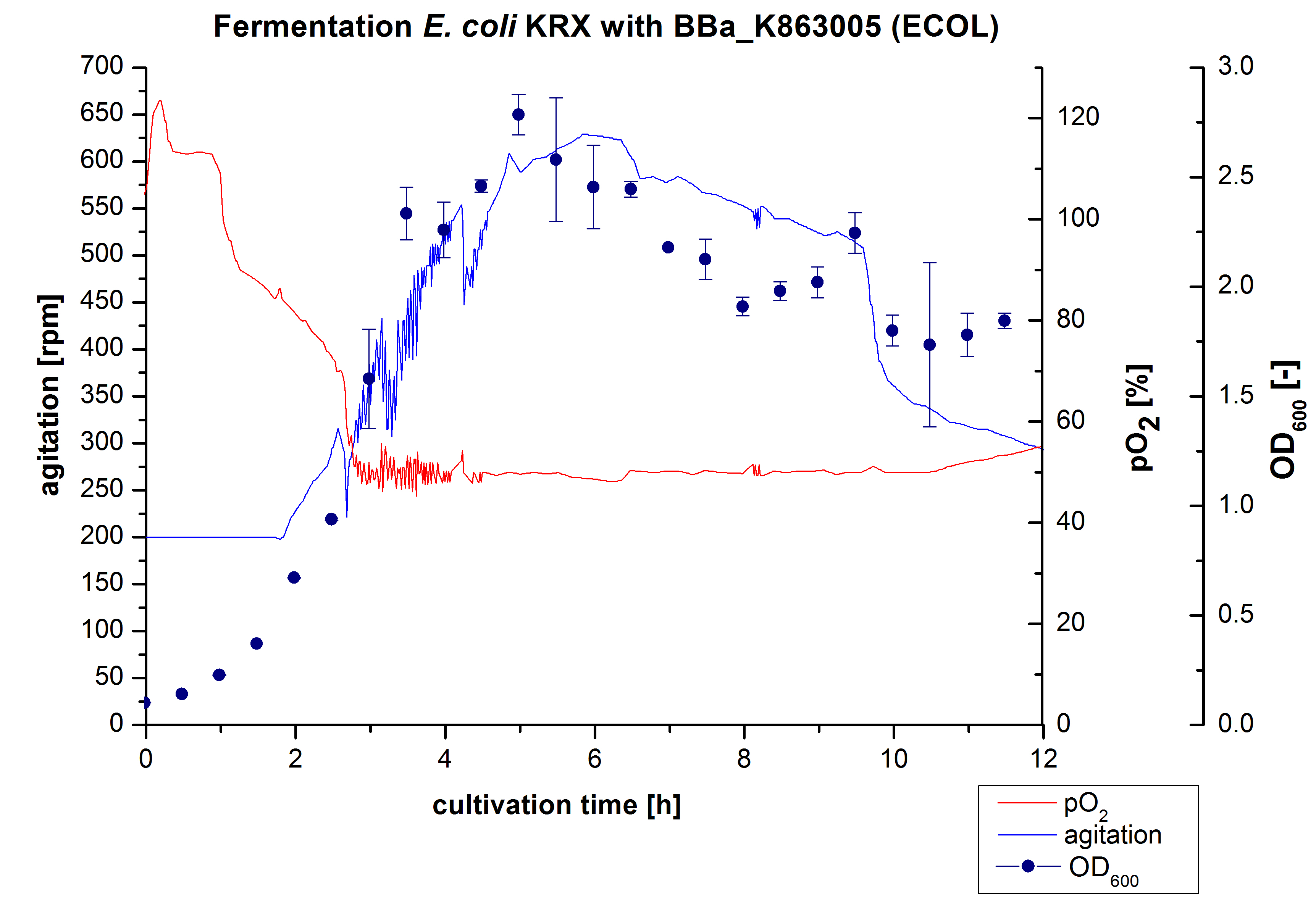

3 L Fermentation E. coli KRX with <partinfo>BBa_K863005</partinfo>

After the measurement of activity of ECOL we made a scale-up and fermented E. coli KRX with <partinfo>BBa_K863005</partinfo> in Infors Labfors with a total volume of 3 L. Agitation speed, pO2 and OD600 were determined and illustrated in Figure 1. The exponential phase started after 1,5 hours of cultivation. The cell growth caused a decrease in pO2. After 2 hours of cultivation the agitation speed increased up to 629 rmp (5,9 hours) to hold the minimal pO2 level of 50 %. Then, after 4 hours there was a break in cell growth due to induction of protein expression. The maximal OD600 of 2,78 was reached after 5 hours. In comparison to E. coli KRX (OD600,max =4,86 after 8,5 hours) and to E. coli KRX with <partinfo>BBa_K863000</partinfo> (OD600,max =3,53 after 10 hours, time shift due to long lag phase) the OD600,max is lower. In the following hours, the OD600,max and the agitation speed decreased and the pO2 increased, which indicates the death phase of the cells. This is caused by the celltoxicity of ECOL (reference: [http://www.dbu.de/OPAC/ab/DBU-Abschlussbericht-AZ-13191.pdf DBU final report]). Therefore they were harvested after 12 hours.

Purification of ECOL

The harvested cells were resuspended in Ni-NTA-equilibrationbuffer, mechanically lysed by homogenization and centrifuged. The supernatant of the lysed cell paste was loaded on the Ni-NTA-column (15 mL Ni-NTA resin) with a flowrate of 1 mL min-1 cm-2. Then the column was washed by 10 column volumes (CV) with Ni-NTA-equilibrationbuffer. The bound proteins were eluted by an increasing Ni-NTA-elutionbuffer step elution from 5 % (equates to 25 mM imidazol) with a length of 60 mL, to 50 % (equates to 250 mM Imidazol) with a length of 60 mL, to 80 % (equates to 400 mM imidazol) with a length of 40 mL and finally to 100 % (equates to 500 mM imidazol) with a length of 80 mL. This strategies was chosen to improve the purification caused by a step by step increasing Ni-NTA-elutionbuffer concentration. The elution was collected in 10 mL fractions. The chromatogram of the BPUL-elution is shown in figure 2:

The chromatogram shows two remarkable peaks. The first peak was detected by a Ni-NTA-equilibrationbuffer concentration of 5 % (equates to 25 mM imidazol) and resulted from the elution of weakly bound proteins. After increasing the Ni-NTA-elutionbuffer concentration to 50 % (equates to 250 mM imidazol) a peak up to a UV-detection signal of 292 mAU was measured. The area of this peak indicates that a high amount of protein was eluted. The corresponding fractions were analysed by SDS-PAGE analysis to detect ECOL. There were no further peaks detectable. The following increasing UV-dectection-signals equates to the imidazol concentration of the Ni-NTA-elutionbuffer. The corresponding SDS-PAGES are shown in figure 3.

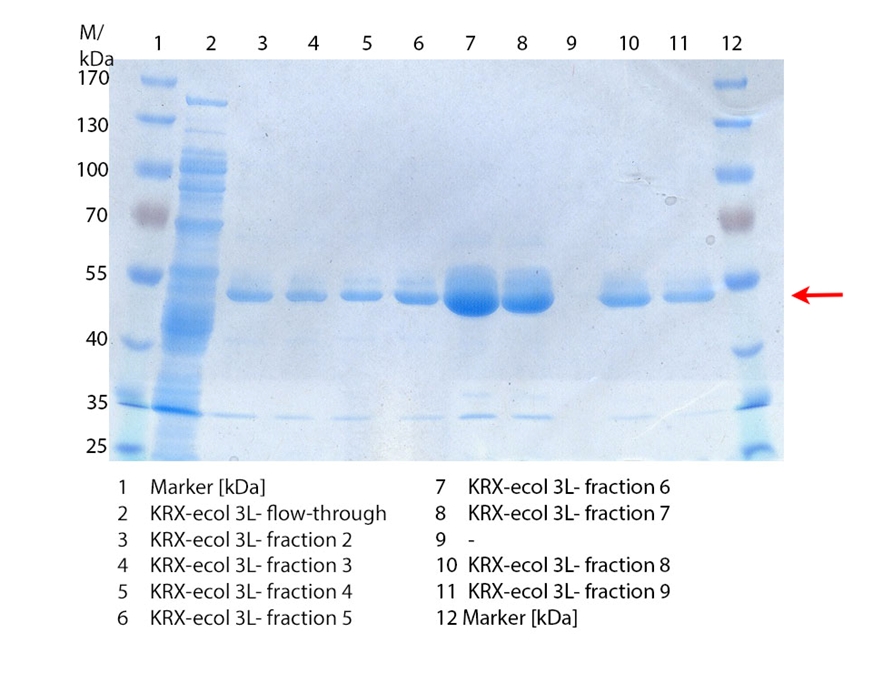

SDS-PAGE of ECOL purification

In figure 3 the SDS-PAGE of the Ni-NTA-Histag purification of the lysed culture ( E. coli KRX containing [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K863005 BBa_K863005]) is illustrated including the flow-through and the fractions 2 to 9. The red arrow indicates the band of ECOL with a molecular weight of 53,4 kDa, which appears in all fractions. The strongest bands appear in fractions 6 and 7. Another small band with a lower molecular weight appears, but was not identified.

Furthermore the bands were analysed by MALDI-TOF and identified as CueO (ECOL).

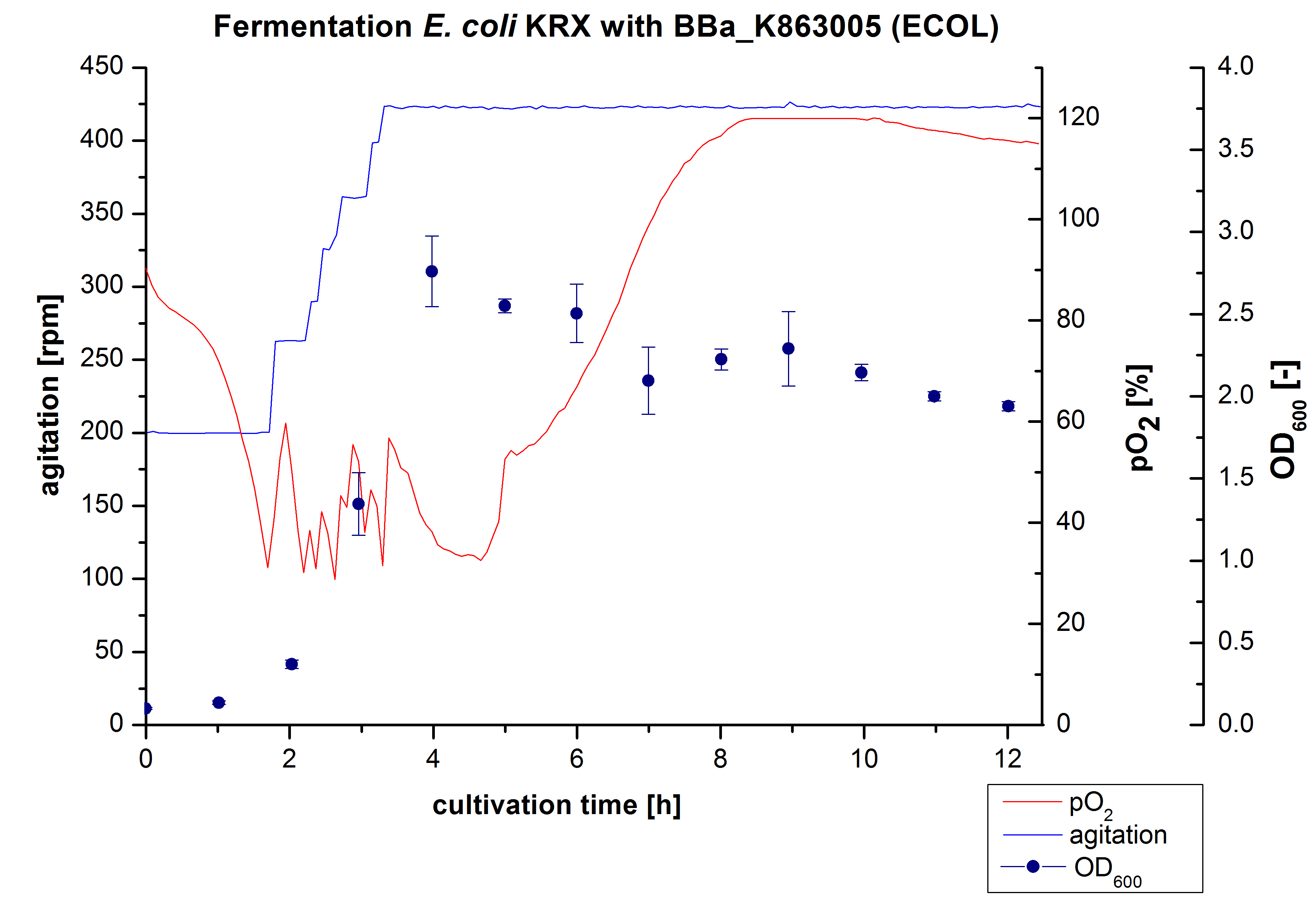

6 L Fermentation E. coli KRX with <partinfo>BBa_K863005</partinfo>

Another scale-up of the fermentation of E. coli KRX with <partinfo>BBa_K863005</partinfo> was made up to a final working volume of 6 L in Bioengineering NFL22. Agitation speed, pO2 and OD600 were determined and illustrated in Figure 3. There was no noticeable lag phase and the cells immediatly began to grow. The cells were in an exponential phase between 2 and 4 hours of cultivation, which results in a decrease of pO2 value and therefore in an increase of agitation speed. After 4 hours of cultivation the maximal OD600 of 2,76 was reached, which is comparable to the 3 L fermentation of E. coli KRX with <partinfo>BBa_K863005</partinfo>. Due to induction of protein expression there is a break in cell growth. The death phase started, which is indicated by an increasing pO2 and a decreasing OD600. This demonstrates the cytotoxity of the laccases for E. coli, which was reported by the [http://www.dbu.de/OPAC/ab/DBU-Abschlussbericht-AZ-13191.pdf DBU]. In comparison to the fermentation of E. coli KRX with <partinfo>BBa_K863000</partinfo> under the same conditions (OD600,max= 3,53), the OD600,max was lower. Cells were harvested after 12 hours.

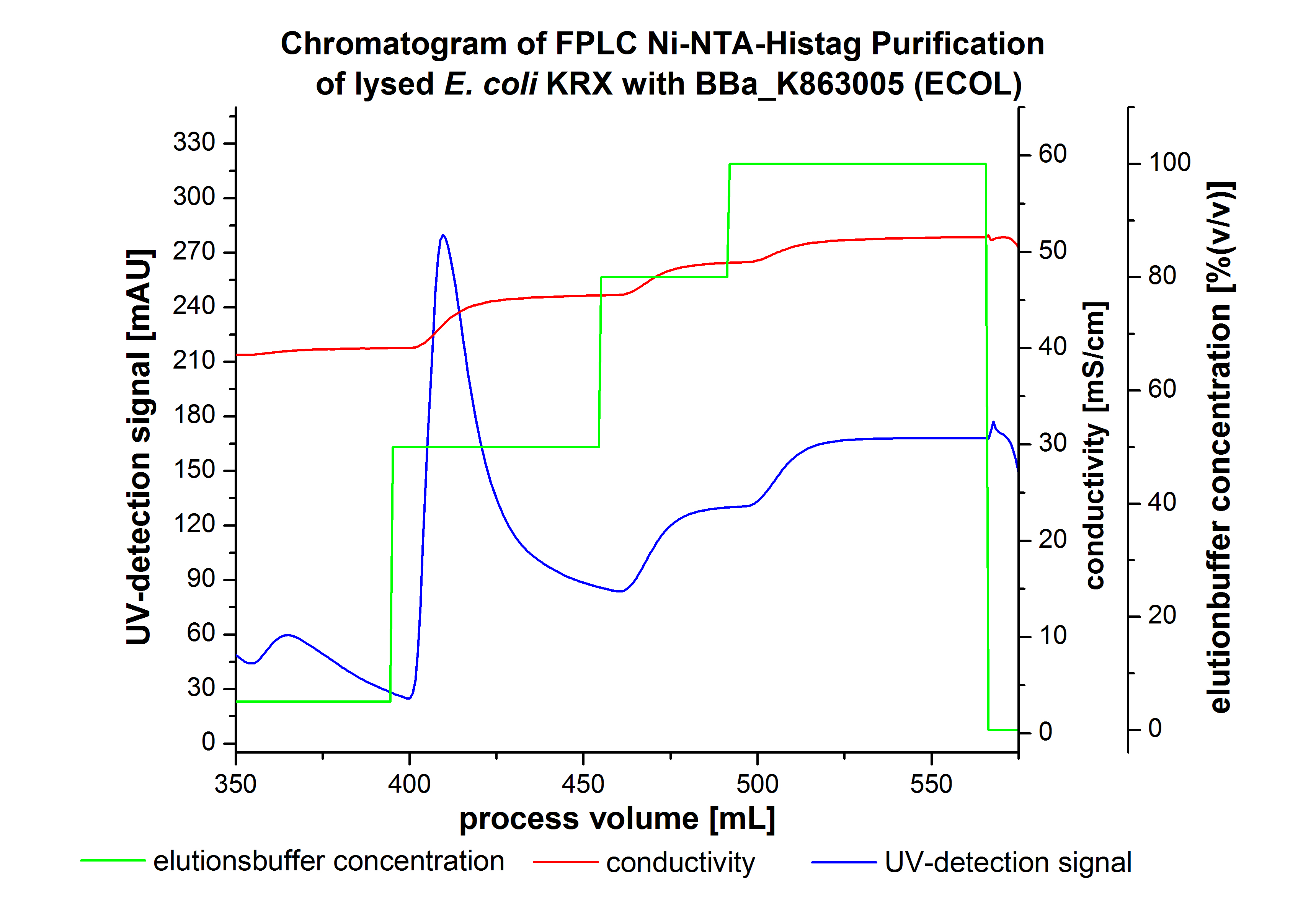

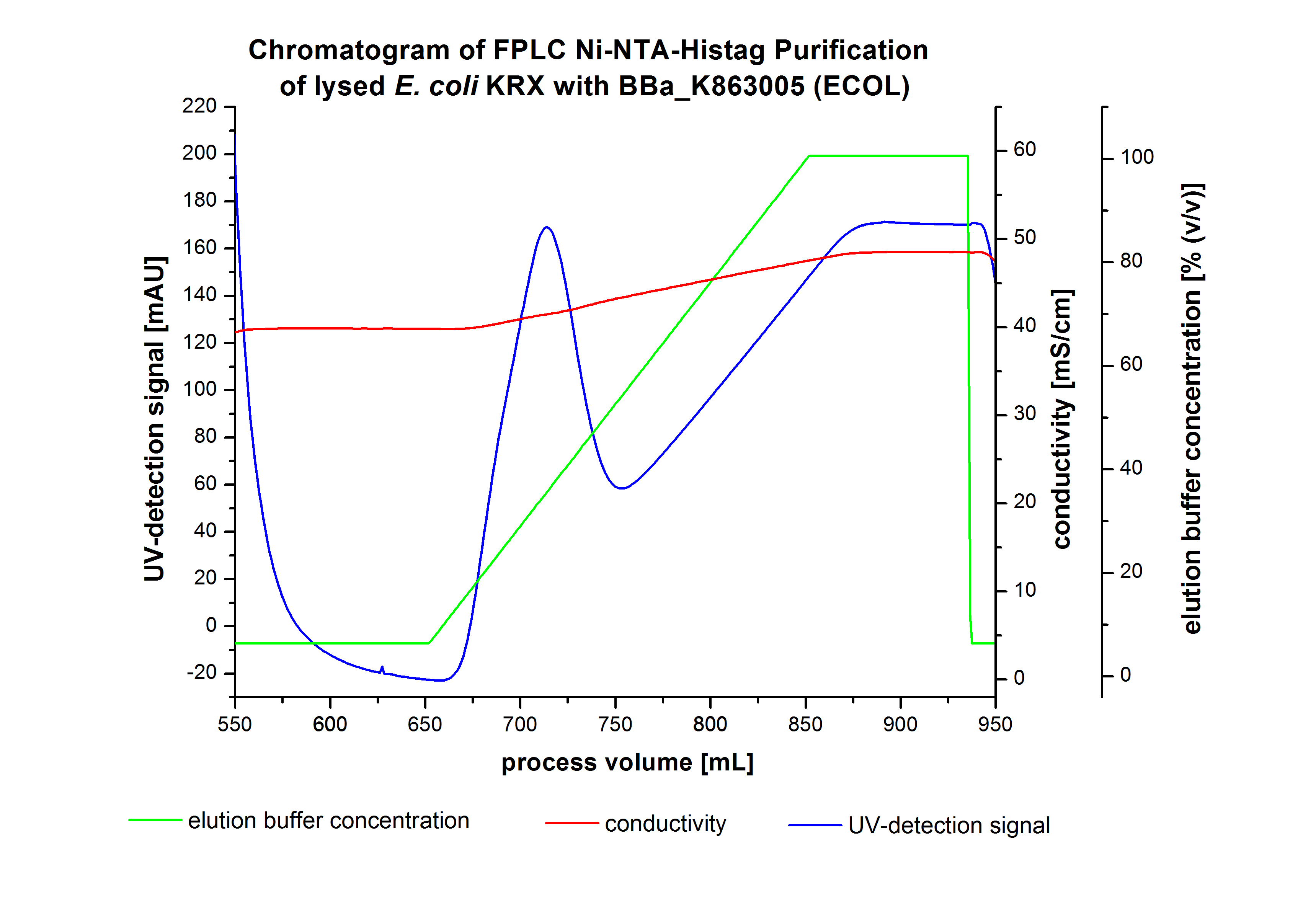

Purification of ECOL

The harvested cells were resuspended in Ni-NTA-equilibrationbuffer, mechanically lysed by homogenization and centrifuged. The supernatant of the lysed cell paste was loaded on the Ni-NTA-column (15 mL Ni-NTA resin) with a flowrate of 1 mL min-1 cm-2. The column was washed by 10 column volumes (CV) with Ni-NTA-equilibrationbuffer. The bound proteins were eluted by an increasing Ni-NTA-elutionbuffer gradient from 0 % to 100 % with a length of 200 mL and the elution was collected in 10 mL fractions. The chromatogram of the ECOL-elution is shown in figure 4:

After washing the column with 10 CV Ni-NTA-elutionbuffer the elution process was started. At a process volume of 670 mL to 750 mL the chromatogram shows a remarkable widespread peak (UV-detection signal 189 mAU) caused by the elution of a high amount of proteins. The run of the curve show a fronting. This can be explained by the elution of weakly bound proteins, which elutes at low imidazol concentrations. A better result could be achieved with a step elution strategy (see purification of the 3 L Fermentation above). To detect ECOL the corresponding fractions were analysed by SDS-PAGE analysis.

SDS-PAGES of ECOL purification

In figure 6 the result of the Ni-NTA-Histag purification of the lysed culture E. coli KRX containing [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K863005 BBa_K863005] (6 L fermentation) including the flow-through, wash and the fractions 1 to 15 (except from fraction 11/12) are shown. The red arrow indicates the band of ECOL with a molecular weight of 53,4 kDa, which appears in all fractions. The strongest bands appear from fractions 3 and 8 with a decreasing amount of other non-specific bands.

Furthermore the bands were analysed by MALDI-TOF and identified as CueO (ECOL).

Laccase from Thermus thermophilus HB27

First some trails of shaking flask cultivations were made with different parameters to define the best conditions for the production of the His-tagged TTHL. Because of no activity in the cell lysate a purification method was established (using Ni-NTA-Histag resin). The purified TTHL could not be detected by SDS-PAGE (theoretical molecular weight of 53 kDa) by using the '' E. coli'' KRX as expression system. Due to this results we decided to change the expression to ''E. coli'' Rossetta-Gami 2. With this expression system the TTHL could be detected by SDS-PAGE as well as MALDI-TOF analysis. To prove the activity of the produced laccase we used a small scale Ni-NTA-column to purify our laccase. The fractionated samples were also tested concerning their activity. A maximal activity of X was reached. After measuring activity of TTHL a scale up was made up to 6 L

Shaking Flask Cultivation

The first trails to produce the Thermo thermophilus-laccase (TTHL) were produced in shaking flask with various designs (from 100 mL-1 to 1 L flasks, with and without baffles) and under different conditions. The parameters we have changed during our screening experiments were the temperature (27 °C,30 °C and 37 °C), different concentrations of chloramphenicol (20-170 µg mL-1), various induction strategies (autoinduction and manual induction), several cultivation times (6 - 24 h) and in absence or presence of 0,25 mM CuCl2. Due to the screening experiments we wasn't able to detect the best conditions for the production with the E. coli KRX chassi. Due to the failed screening results we decided to produce the TTHL in an other E. coli strain called E. coli Rosetta-Gami 2 containing <partinfo>BBa_K863012</partinfo>. We decided to use E. coli Rosetta-Gami 2 becaus of his skill to translate rare codons. We produced our TTHL with the following conditions:

- flask design: shaking flask without baffles

- medium: LB-Medium

- antibiotics: 60 µg mL-1 chloramphenicol and 300 µg mL-1 ampicillin

- temperature: 37 °C

- cultivation time: 24 h

The reproducibility and repeatability of the measured data and results were investigated for the shaking flask and bioreactor cultivation with n≤3.

The Results of the SDS-PAGE analysis are shown in the following images:

SDS PAGES!!!!!

ACTIVITÄTSMESSUNGEN VOM ERSTEN AKTIVEN B PUMI!!!!!!

Fermentation of E. coli KRX with <partinfo>BBa_K863012</partinfo>

After measuring activity of TTHL we made a scale-up and fermented E. coli Rosetta-Gami 2 with <partinfo>BBa_K863000</partinfo> in Bioengineering NFL22 with a total volume of 6 L. Agitation speed, pO2 and OD600 were determined and illustrated in Figure 1. The cells immediatly began to grow and therefore the pO2 decreased up to a value of 0 %, because the breakdown of the control unit. After a cultivation time of 9 hours the agitation speed was increased up to a 500 rpm, which resulted in a pO2 value of more than 100 % for the rest of the cultivation. During the whole process the OD600 increased slowly in comparison to the fermentation of E. coli KRX with <partinfo>BBa_K863000</partinfo> or <partinfo>BBa_K863005</partinfo>. The maximal OD600 was reached after 19 hours of cultivation, when the cells were harvested.

Purification of TTHL

The cells were harvested and resuspended in Ni-NTA-equilibrationbuffer, mechanically lysed by homogenization and centrifuged. After preparing the cell paste we did not have the possibility to purificate the TTHL with the 15 mL. To detect and to analyse our produced TTHL we implement a small scale purification of 6 mL of the supernatant with a 1 mL Ni-NTA-column. The results of the SDS-PAGE analysis are shown the following images:

SDS-PAGE of purification TTHL

Laccase from Bacillus halodurans C-125

First some trails of shaking flask cultivations were made with various parameters to identify the best conditions for the production of the His-tagged BHAL. Because of no activity in the cell lysate a purification method was established (using Ni-NTA-Histag resin). The BHAL could not be detected by SDS-PAGE (theoretical molecular weight of 56 kDa) by using the '' E. coli'' KRX as expression system. Due to this results we decided to change the expression to ''E. coli'' Rossetta-Gami 2. With this expression system the BHAL could be found by SDS-PAGE as well as MALDI-TOF analysis. To prove the activity of the produced laccase we used a small scale Ni-NTA-column to purify our laccase. The fractionated samples were also tested concerning their activity. A maximal activity of X was reached. A scale up could not be implemented yet.

Laccase from Trametes versicolor

Immobilization

Subtrate Analytics

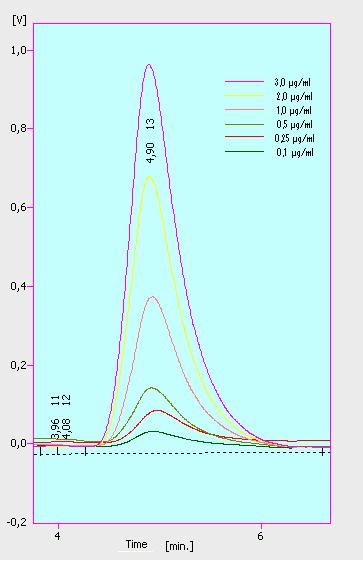

Dilutioin series

At first we mesured dilution series of all different substrates.

- estrogens

- estradiol

- estrone

- ethinyl estradiol

- analgesics

- diclofenac

- naproxen

- ibuprofen

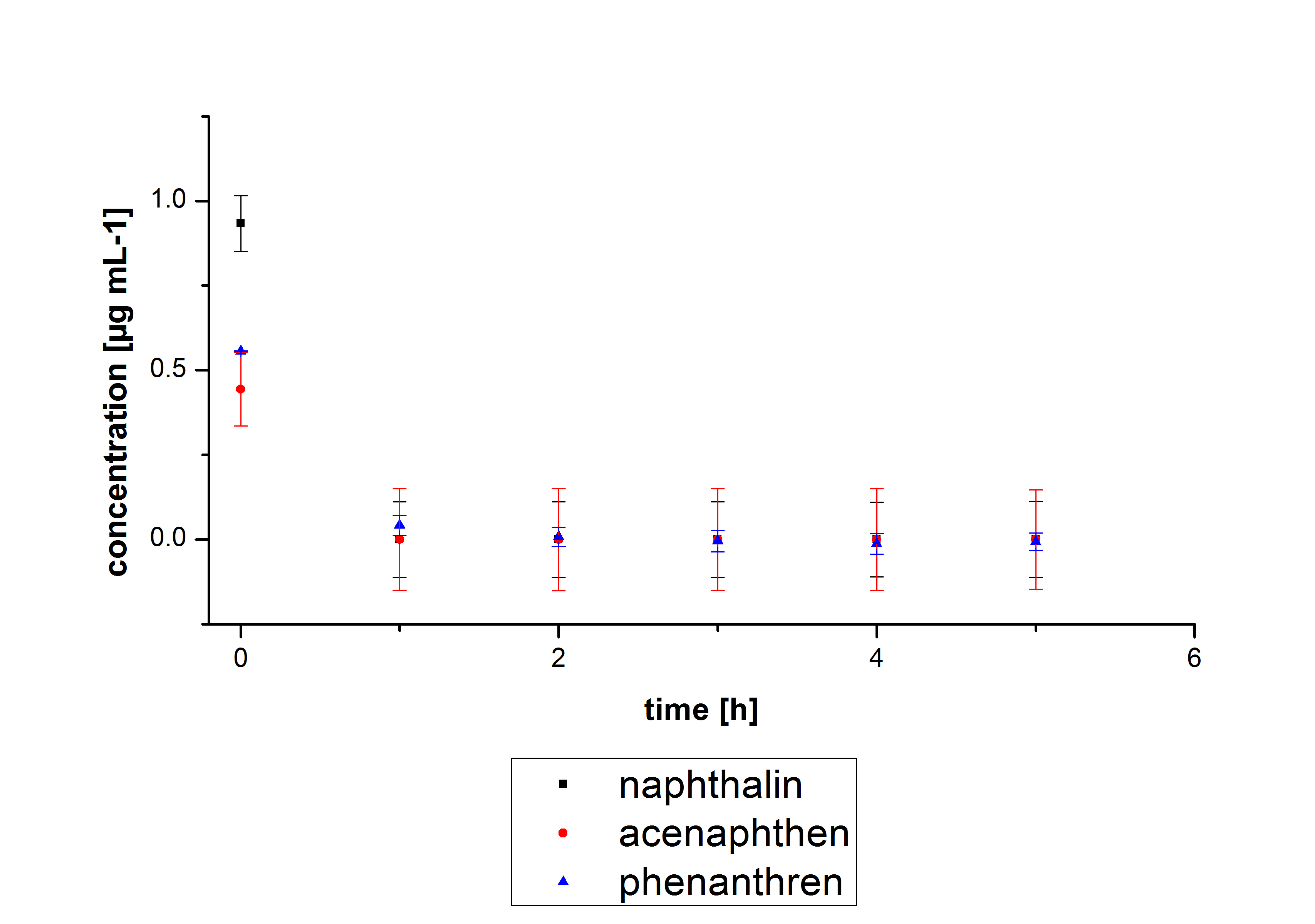

- PAH´s

- naphthalene

- acenaphthene

- phenantrene

- anthracen

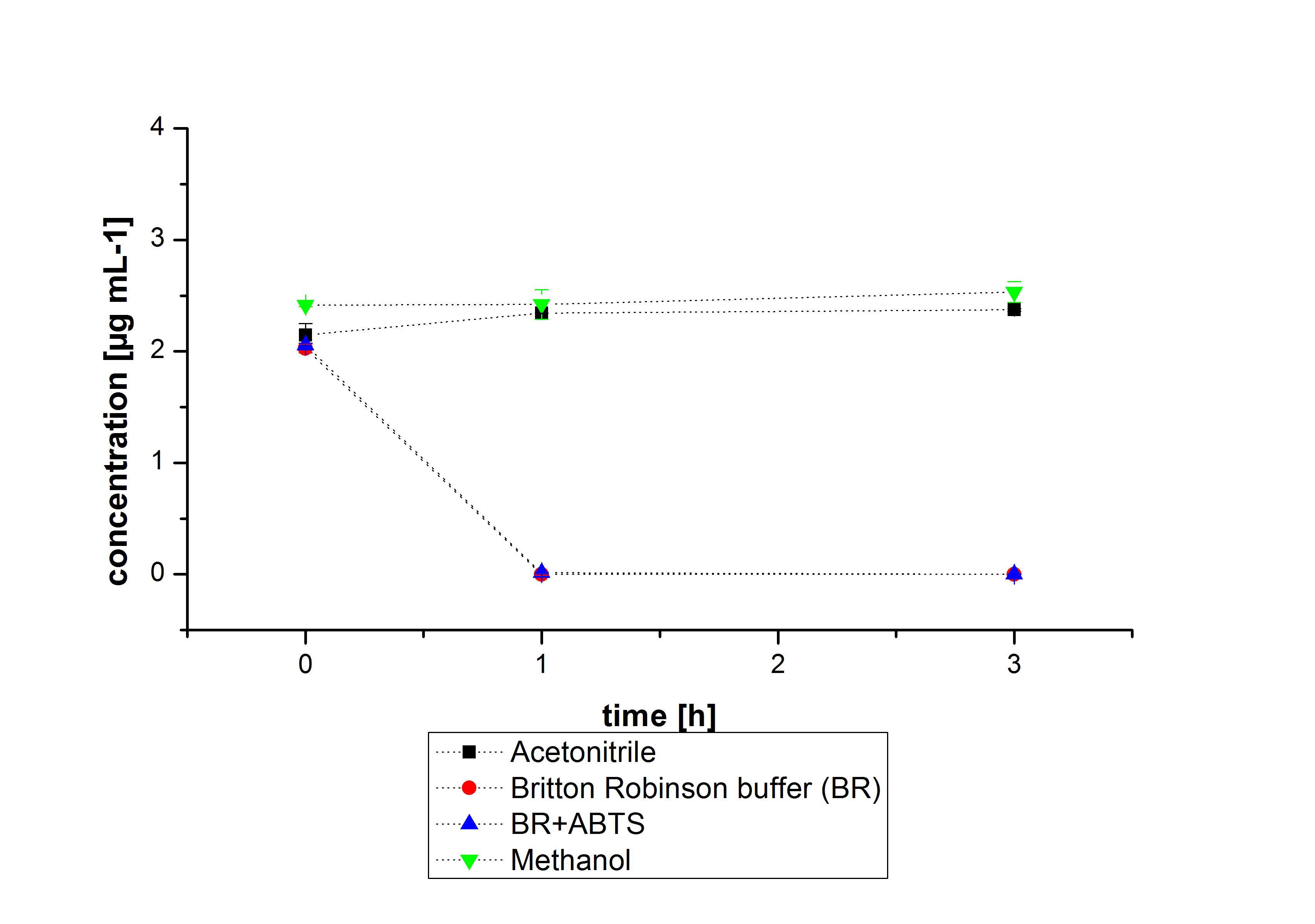

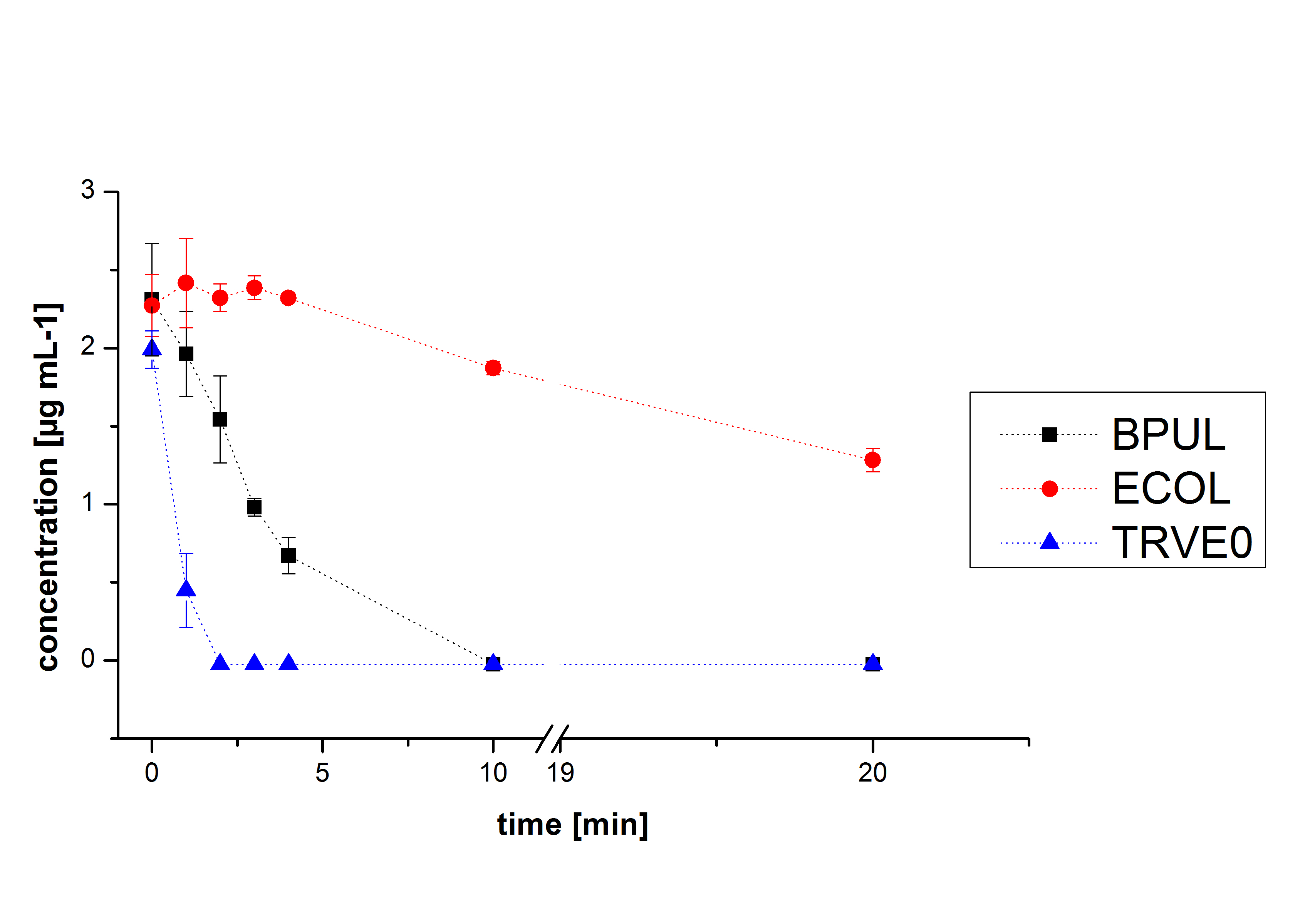

Negative controls

Degradation

Cellulose binding domain

Introduction

In the field of cheap protein-extraction cellulose binding domains (CBD) have made themselfes a name. A lot of publications have been made, concerning a cheap strategy to capture a protein from the cell-lysate with a CBD-tag. Also enhanced segregation with CBD-tagged proteins have been observed. Here the idea is different, we want to take advantage of the binding capacity of binding domains not only for purification reasons (it is still a benefit), but also as an immobilizing-protocol for our laccases.

To make a purification and immobilization-tag out of a protein domain, there are a lot of decisions and characterizations you have to get through.

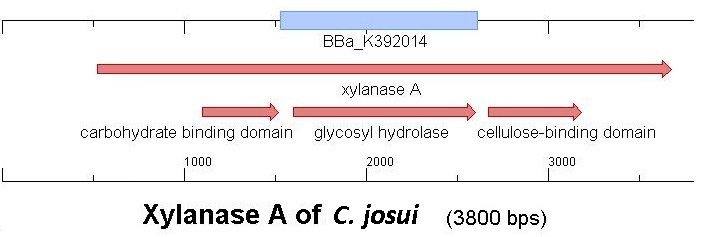

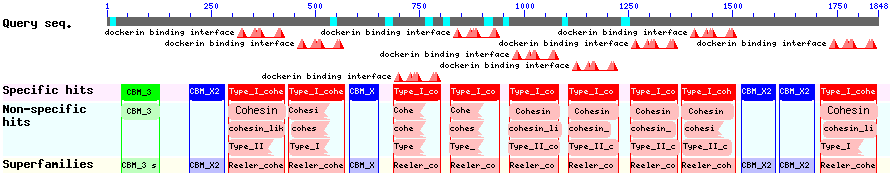

Starting with the choice of the binding domain, the first limitation is accessibility. Our first place to look was, of course the [http://partsregistry.org Partsregistry]. We found a promising Cellulose binding motif of the C. josui Xyn10A gene (<partinfo>BBa_K392014</partinfo>) there and ordered it right from the spot for our project. After some research later concerning the sequence of that BioBrick it turned out that the part is not the CBD of the Xylanase as it should be, but the glycosyl hydrolase domain of the protein (Figure 1). This result made the part useless for our project ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K392014:Experience complete review]) and it was the only binding domain in the [http://partsregistry.org Partsregistry] that fitted to our project.

So we started to search the accessible organisms we had via NCBI for binding-domains, -proteins and -motifs and asked in work-groups if they could help us out. The results of our database research were only two chitin/carbohydate binding modules within the Bacillus halodurans genome (we ordered that stain for it's laccase <partinfo>BBa_K863020</partinfo>). One is in the [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide/289656506?report=genbank&log$=nuclalign&blast_rank=1&RID=0JPT9WMS01N Cochin chitinase gene] and the other in a [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/BAB05022.1 chitin binding protein].

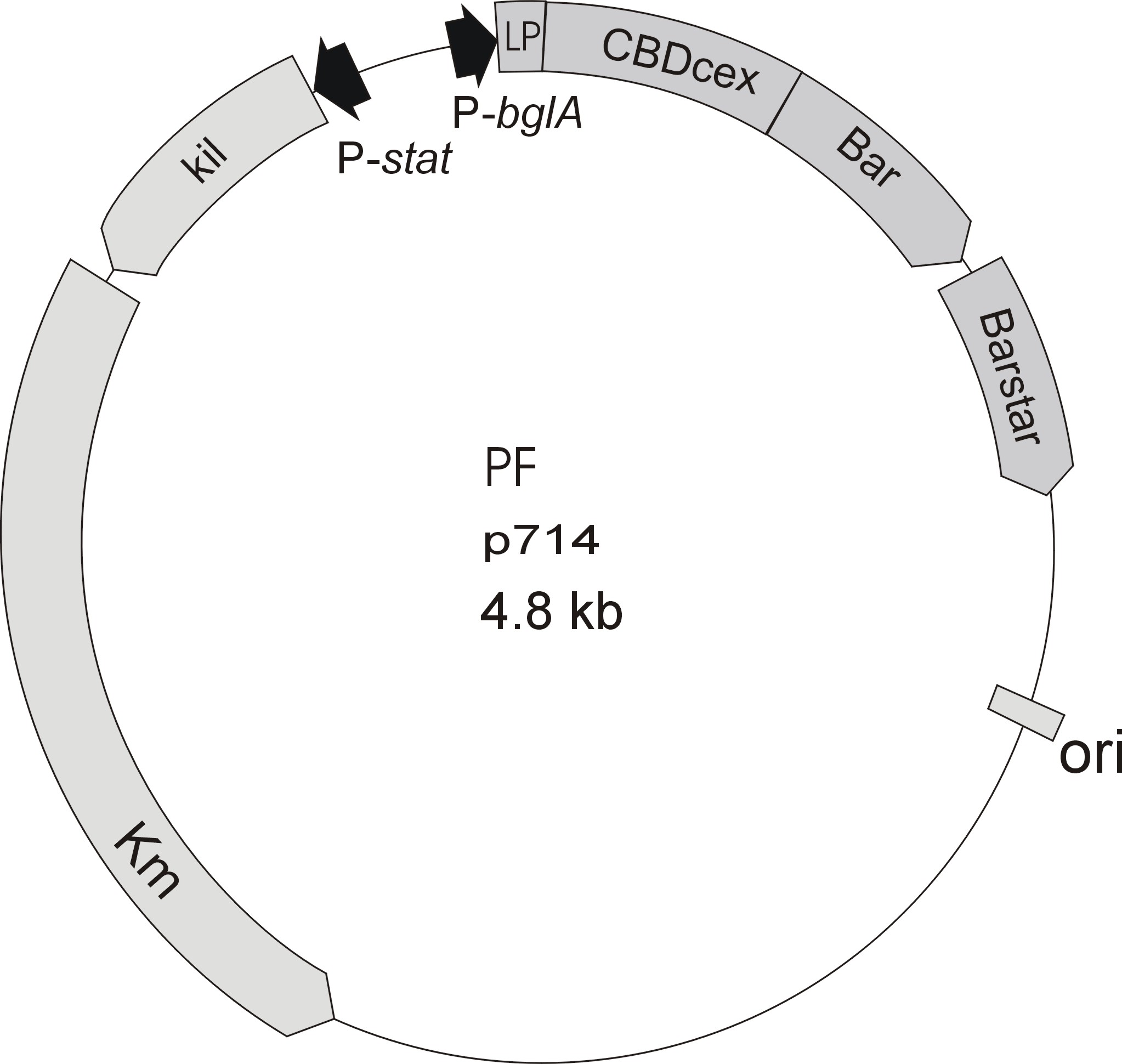

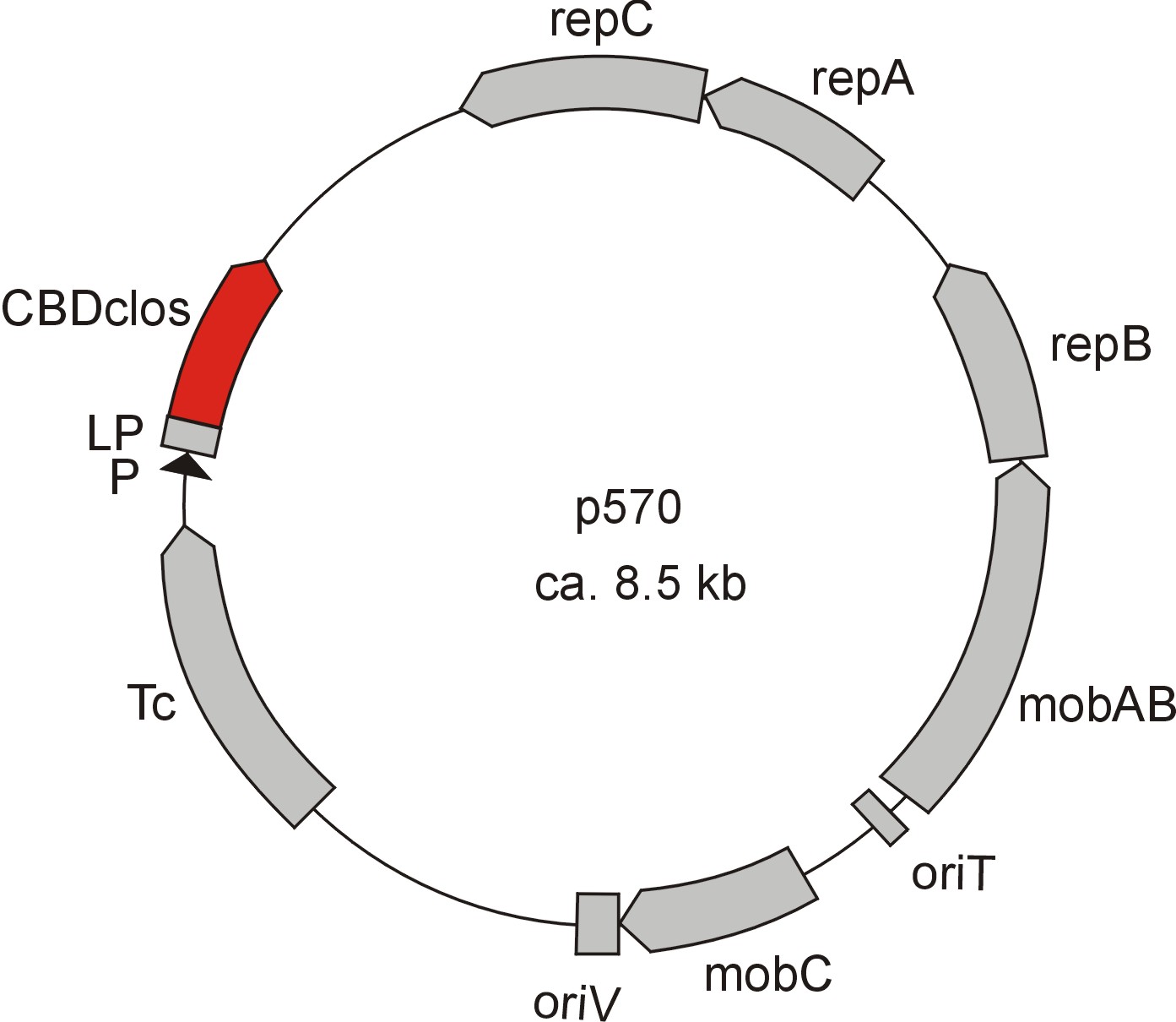

Meanwhile the Fermentation of our university group offered use two plasmids (p570 & p671), containing two different cellulose binding domains. The Cellulose binding domain of the [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide/327179207?report=genbank&log$=nucltop&blast_rank=3&RID=152ZCN0E01N Cellulomonas fimi ATCC 484 exoglucanase gene] (CBDcex) and the Cellulose binding domain of [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/M73817 Clostridium cellulovorans cellulose binding protein gene (cbp A)] (CBDclos). At that point we decided to use these two domains. Staying within the cellulose binding domain-family and leave other protein domains like carbohydrate binding domains aside will keep the results comparable. Like changing to a different binding material would change the binding capacities of both domains in the same way. Also we would stay within bacterial CBD and didn't have to spend time thinking about post-translational modification and glycosylation.

To get to know more about these two domains, their properties and their proteins we consulted NCBI and used the [http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ BLAST]-tool to identify the cellulose binding domains and ExPASy-tools for further measurements.

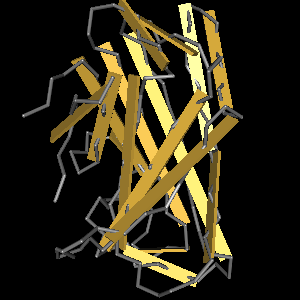

The CBD of the Cellulomonas fimi ATCC 484 exoglucanase gene (Figure 6) is a 100 amino acid long domain, close to the C-terminal ending of the protein with a theoretical pI of 8.07 and a molecular weight of 10.3 kDa. It is classified to be stable and belongs to the Cellulose Binding Modul family 2 (pfam00553/cl02709). This means two tryptophan residues are involved in cellulose binding, this type of CBD is only found in bacteria. Also a CBM49 Carbohydrate binding domain is found within the protein domain, where [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17322304?dopt=Abstract binding studies] have shown, that it binds to crystalline cellulose, which could be a possible target for immobilization.

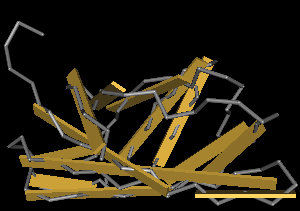

The CBD of the [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/M73817 Clostridium cellulovorans cellulose binding protein gene (cbp A)] on the other hand is a N-terminal domain with 92 amino acids, theoretical pI of 4.56 and ist also classified as stable. It belongs to the Cellulose Binding Modul family 3 (pfam00942/cl03026) and is part of a very large cellulose binding protein with four other carbohydrate binding moduls and a lot of docking interfaces for the proteins in its amino acid sequence (Figure 7).

The Binding Assay

To measure the capacity and strength of the bonding between the cellulose binding domains and different types of cellulose many different assays have been made. One of the simplest and most often used is the fusion of the CBD to a reporter-protein, especially [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22305911a green or red fluorescent protein (GFP/RFP)] is very common. The place of the CBD is measured through the fluorescence of the fused GFP and quantification can easily been done.

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18573384 Protocol]:

- Harvest the E coli-cells producing the fusion-protein of CBD and GFP and centifuge 10 minutes at top speed.

- Re-suspend the cell-pellet in 50 mM Tris-HCl-Buffer (pH 8.0).

- Break down cells via sonication.

- Centrifuge at top speed for 20 minutes to get rid of the cell-debris.

- Take the supernatant and measure the emission at 511 nm (excitation at 501 nm) (<partinfo>E0040</partinfo>)

- Mix a definite volume of lysate with a definite volume or mass of e.g. crystalline cellulose (CC) or reactivated amorphous cellulose (RAC)

- Wait 15 (RAC) to 30 (CC) minutes

- Take supernatant and measure the emission at 511 nm again.

- The difference between the first an the second measurement is the relative quantity of what has bound to the cellulose.

Cloning of the Cellulose Binding Domains

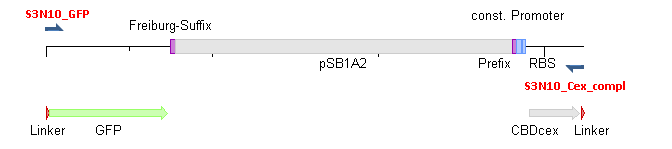

The cloning of the CBDs should fit to the cloning of our laccases, so we designed the BioBricks with a T7-promoter and the B0034 RBS to have a similar method of cultivation. After we investigated the restriction-sites it showed, that at least for the characterization of the CBDs a quick in-frame assembly of the CBDs and a GFP would be possible, because nether the CBDs nor the GFP (<partinfo>I13522</partinfo>) of the partsregistry inherits a AgeI- or NgoMIV-site, which makes Freiburg-assembly possible. To do so, we designed primers for the constructs <partinfo>BBa_K863101</partinfo> (CBDcex(T7)), carrying the CBDcex domain from the C. fimi exoglucanase and <partinfo>BBa_K863111</partinfo> (CBDclos(T7)), carrying the CBDclos domain from the C.cellulovorans binding protein. The protein-BLAST of the two CBDs gave a exact picture of which bases are count to the binding domains and which are not. To be sure not to disturb the folding anyway we kept 6 to 12 bases up and downstream of the domains as conserved sequences. Even if the [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K863101 CBDcex]is a N-terminal domain we chose to make the domains N-terminal, so the BioBrick already carries all regulatory parts and the linked protein can easily be exchanged. This also would be nice for other people using this part.

| CBDcex_T7RBS | 80 | TGAATTCGCGGCCGCTTCTAGAGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAAAGAGGAGAAATAATGGGT CCGGCCGGGTGCCAGGT |

| CBDcex_2AS-Link_compl | 56 | CTGCAGCGGCCGCTACTAGTATTAACCGGTGCTGCCGCCGACCGTGCAGGGCGTGC |

| CBDclos_T7RBS | 73 | CCGCTTCTAGAGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAAAGAGGAGAAATAATGTCAGTTGAATTTTACAACTCTAAC |

| CBDclos_2ASlink_compl | 63 | CTGCAGCGGCCGCTACTAGTATTAACCGGTGCTGCCTGCAAATCCAAATTCAACATATGTATC |

The listed complementary primers added, besides the Freiburg-suffix, a two amino acid Glycine-Serine-linker to the end of the CBDs. This is a very short linker, but as GFP-experts and [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17394253 publications] described GFP and CBDs are very stable proteins and should cope with a very short linker. The benefit of a short linker is that protease activity is kept minimal.

The GFP <partinfo>K863121</partinfo> we wanted to use for the assay was an alternated version of the <partinfo>BBa_I13522</partinfo>. We made primers that added a Freiburg-pre- and suffix to the GFP coding sequence and a His-tag to the C-terminus to get it purified for the measurements. This part <partinfo>BBa_K863121</partinfo> (GFP_His) should be easily added to the CBDs and assemble to the fusion-proteins <partinfo>BBa_K863103</partinfo> CBDcex(T7)+GFP_His] and <partinfo>BBa_K863113</partinfo> CBDclos(T7)+GFP_His]).

| GFP_Frei | 54 | TACGGAATTCGCGGCCGCTTCTAGATGGCCGGCATGCGTAAAGGAGAAGAACTT |

| GFP_His6_compl | 74 | CTGCAGCGGCCGCTACTAGTATTAACCGGTGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGTTTGTATAGTTCATCCATGCCATGTG |

Since we added a His-tag to the end of the GFP, we had to make a alternated version of the <partinfo>BBa_I13522</partinfo> to compare binding of GFP with and without CBD. Therefore we made a forward primer, to amplify the whole <partinfo>BBa_I13522</partinfo> and used the GFP_His_compl-primer to add the His-tag to the C-terminus.

| GFP_FW_SV | 39 | acgtcacctgcgtgtagctCGTAAAGGAGAAGAACTTTT |

Due to bad cleavage efficiency at the PstI restiction-site in nearly all PCR-products the cloning of the CBDs ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K863102 CBDcex(T7)] and [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K863112 CBDclos(T7)])and especially the insertion of [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K863121 GFP_His] to the CBDs took a lot more time as expected. This was because, while designing the primers, we missed to add additional base pairs from the cleavage-site to the termini to increase the efficiency to standard. When we got aware of the problem, cloning got a lot quicker and more successful.

As the project went on and the T7-constructs didn't seem to work one suspected reason was that a stop codon (TAA) that accidentally resulted between the RBS and ATG could be the reason for that. To solve the problem we started to change to a constitutive promoter (<partinfo>BBa_J61101</partinfo>) using the Freiburg-assembly. Therefore Freiburg forward primers for the CBDs were made.

| CBDcex_Freiburg-Prefix | 54 | GCTAGAATTCGCGGCCGCTTCTAGATGGCCGGCGGTCCGGCCGGGTGCCAGGTG |

| CBDclos_Freiburg-Prefix | 57 | GCTAGAATTCGCGGCCGCTTCTAGATGGCCGGCTCATCAATGTCAGTTGAATTTTAC |

The second advantage of these primers were, that the order of the fusion proteins could easily been changed, when a Freiburg suffix-primer for the GFP would be available, so we ordered that.

| GFP_Freiburg_compl | 61 | ACGTCTGCAGCGGCCGCTACTAGTATTAACCGGTTTTGTATAGTTCATCCATGCCATGTGT |

Sadly the primers arrived just a few days before wiki freeze and we had no time to test that. The switching to the constitutive promoter had no obvious effect (no green colonies or culture). Changing the expression strain of E. coli BL21 didn't do no positive effect ether. Which led us to the conclusion, that besides further information the problem has to be the space in between the two proteins and the CBD and GFP must hamper each other from folding correctly. To test and solve this a very long linker with three serines followed by ten asparagines should be assembled in the already existing parts via a blunt end cloning. This also is right at hand, just wasn't successful in the time which was left.

| S3N10_Cex_compl | 40 | TTGTTGTTGTTCGAGCTCGAGCCGACCGTGCAGGGCGTGC |

| S3N10_Clos_compl | 40 | TTGTTGTTGTTCGAGCTCGAGCTGCCGCCGACCGTGCAGG |

| S3N10_GFP | 40 | CAATAACAATAACAACAACCGTAAAGGAGAAGAACTTTTC |

Literature

Biotechnol Bioeng. 2007 Oct 15;98(3):599-610. Strategy for selecting and characterizing linker peptides for CBM9-tagged fusion proteins expressed in Escherichia coli. Kavoosi M, Creagh AL, Kilburn DG, Haynes CA. J Biol Chem. 2007 Apr 20;282(16):12066-74. Epub 2007 Feb 23. A tomato endo-beta-1,4-glucanase, SlCel9C1, represents a distinct subclass with a new family of carbohydrate binding modules (CBM49). Urbanowicz BR, Catalá C, Irwin D, Wilson DB, Ripoll DR, Rose JK. Protein Expr Purif. 2012 Apr;82(2):290-6. Epub 2012 Jan 28. Cellulose affinity purification of fusion proteins tagged with fungal family 1 cellulose-binding domain. Sugimoto N, Igarashi K, Samejima M. Anal Chim Acta. 2008 Jul 28;621(2):193-9. Epub 2008 May 27. Bioseparation of recombinant cellulose-binding module-proteins by affinity adsorption on an ultra-high-capacity cellulosic adsorbent. Hong J, Ye X, Wang Y, Zhang YH.

Shuttle vector

Collaboration with UCL

The BioBrick [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K729002 BBa_K729002] from the University College London was characterized by us using our Chassi (''E. coli'' KRX and our acitvity assay. We cultivcate a ''E. coli'' KRX containing [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K729002 BBa_K729002] in 50 mL shaking flask for 12 h. The harvested cells were lysed and the supernatant was purified from substances with a low molecular weight. The purified supernatant analyzed by SDS-PAGE analysis, our etablished activity assay as well as MALDI-TOF. A maximal activity of X was reached. To compare the laccase the University College London we cultivated the ''E. coli'' KRX and ''E. coli'' KRX containing [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K863005 BBa_K7863005].

Introduction

Cultivation

PCIL - Laccase from Pycnoporus cinnabarinus

TVEL5 - Laccase from Trametes versicolor

TVEL10 - Laccase from Trametes versicolor

TVEL13 - Laccase from Trametes versicolor

TVEL20 - Laccase from Trametes versicolor

| 55px | | | | | | | | | | |

"

"