Team:Tianjin/Project/Regulation

From 2012.igem.org

Austinamens (Talk | contribs) (→Background) |

Austinamens (Talk | contribs) (→Completely Synthesizing the Genome of Mycoplasma Genitalium using Yeast Assembler) |

||

| Line 125: | Line 125: | ||

===Completely Synthesizing the Genome of Mycoplasma Genitalium using Yeast Assembler=== | ===Completely Synthesizing the Genome of Mycoplasma Genitalium using Yeast Assembler=== | ||

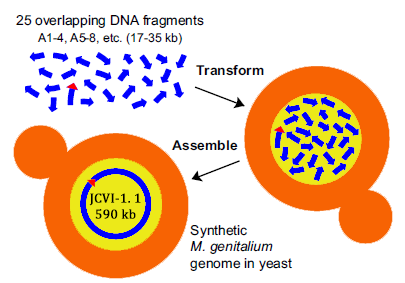

In 2008, Gibson from the J. Craig Venter Institute, published an article “one-step assembly in Yeast of 25 overlapping DNA fragments to form a complete synthetic Mycoplasma genitalium genome”. In the article, the author transformed 25 overlapping DNA fragments into Yeast, homologous recombination occurs, and then the whole genome is synthesized. | In 2008, Gibson from the J. Craig Venter Institute, published an article “one-step assembly in Yeast of 25 overlapping DNA fragments to form a complete synthetic Mycoplasma genitalium genome”. In the article, the author transformed 25 overlapping DNA fragments into Yeast, homologous recombination occurs, and then the whole genome is synthesized. | ||

| - | [[file:TJU2012-Proj-LMR-fig-6.png|thumb|500px|center|'''Figure 6.''' Synthetic Mycoplasma genitalium genome (from "One-step assembly in yeast of 25 overlapping DNA fragments to form a complete synthetic Mycoplasma genitalium genome")]] | + | [[file:TJU2012-Proj-LMR-fig-6.png|thumb|500px|center|'''Figure 6.''' Synthetic Mycoplasma genitalium genome (from "One-step assembly in yeast of 25 overlapping DNA fragments to form a complete synthetic ''Mycoplasma genitalium genome''")]] |

Construction of a synthetic M. genitalium genome in yeast. Yeast cells were transformed with 25 different overlapping A-series DNA segments (blue arrows; ~17 kb to35 kb each) composing the M. genitalium genome. To assemble these into a complete genome, a single yeast cell (tan) must take up at least one representative of the 25 different DNA fragments and incorporate them in the nucleus (yellow), where homologous recombination occurs. This assembled genome, called JCVI-1.1, is 590,011 bp, including the vector sequence (red triangle) shown internal to A86 – 89. | Construction of a synthetic M. genitalium genome in yeast. Yeast cells were transformed with 25 different overlapping A-series DNA segments (blue arrows; ~17 kb to35 kb each) composing the M. genitalium genome. To assemble these into a complete genome, a single yeast cell (tan) must take up at least one representative of the 25 different DNA fragments and incorporate them in the nucleus (yellow), where homologous recombination occurs. This assembled genome, called JCVI-1.1, is 590,011 bp, including the vector sequence (red triangle) shown internal to A86 – 89. | ||

Revision as of 03:19, 27 September 2012

Background

Metabolic Regulation

Cell metabolism is the foundation of cell growth, secretion, differentiation, etc. as well as the core process of the modern fermentation technology that can make large impact on the quality and output of product.

However the modern metabolic regulation of strains has a large amount of areas for improvement. Take the most common E. coli as example. At present, most of the regulation means is to use a single promoter to construct specific operon gene cluster to achieve the regulation with the addition of certain inducers induction of a specific protein. But this induced expression is typically unidirectional, irreversible and it needs to build many complex operons’ gene structure to construct multiple logical regulation, this will produce a plenty of limitation.

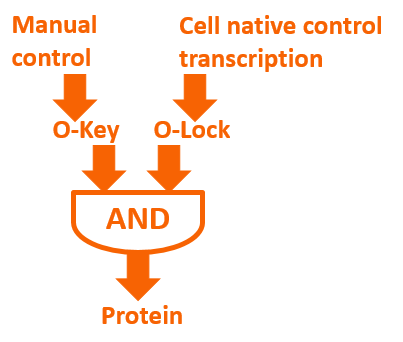

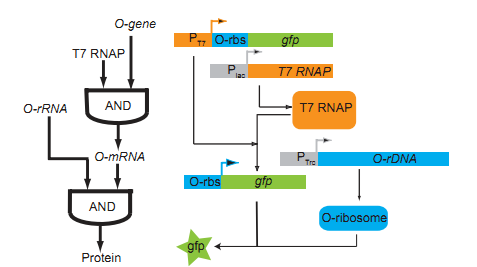

If we add our O-Key into the expression system, a novel regulation means will exist on the level of translation. Meanwhile, we can combine O-Key with the traditional transcription regulation to create logic gate regulation structure like “AND” gate. The logic gate working with normal close and normal open promoter can constitute multiple “AND/OR/NOR” logic gate control system which has more simple structure compared to traditional regulation.

The Difficulty of Large Fragments Assembly

The general digestion connection will leave scar and will be limited by the specific cleavage sequences.

Long PCR fragment will suffer the decline of success rate and distortion, etc.

However, the construction of some large fragments cannot be avoided, so the development of a low-cost, simple operation, good fidelity, a little limiting factor large DNA fragment assembly method is particularly important.

Yeast Assembler

History

Yeast Assembler is based on in vivo homologous recombination in yeast. As for its high efficiency and ease to work with, in vivo homologous recombination in yeast has been widely used for gene cloning, plasmid construction and library creation. In the early of 2008, Zengyi Shao from University of lllinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, used such a method to construct biochemical pathways. Such a method, for its high efficiency in assembling multiple genes, received great popularity since its appearance.

Principles

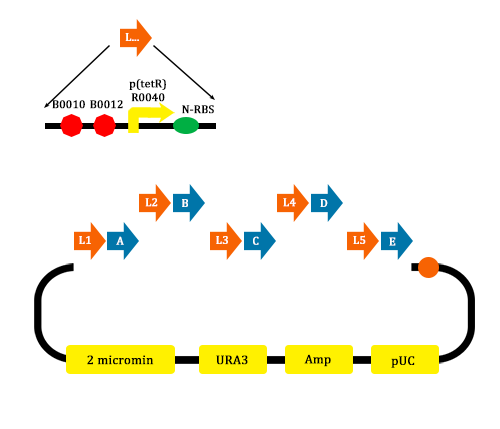

One step assembly into a vector.

When parts are transformed all parts into Yeast, homologous recombination occurs at the site “x”, and then all little parts are integrated into a vector.

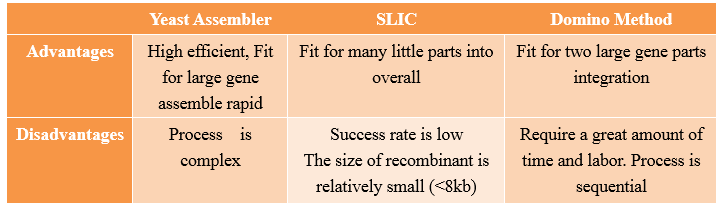

Advantages and Disadvantages

Compared with other methods,the “Yeast assembler” are more efficient and useful for large gene assemble.

Completely Synthesizing the Genome of Mycoplasma Genitalium using Yeast Assembler

In 2008, Gibson from the J. Craig Venter Institute, published an article “one-step assembly in Yeast of 25 overlapping DNA fragments to form a complete synthetic Mycoplasma genitalium genome”. In the article, the author transformed 25 overlapping DNA fragments into Yeast, homologous recombination occurs, and then the whole genome is synthesized.

Construction of a synthetic M. genitalium genome in yeast. Yeast cells were transformed with 25 different overlapping A-series DNA segments (blue arrows; ~17 kb to35 kb each) composing the M. genitalium genome. To assemble these into a complete genome, a single yeast cell (tan) must take up at least one representative of the 25 different DNA fragments and incorporate them in the nucleus (yellow), where homologous recombination occurs. This assembled genome, called JCVI-1.1, is 590,011 bp, including the vector sequence (red triangle) shown internal to A86 – 89.

Synthesizing the Pathway Needed for Synthesizing Violacein

Background

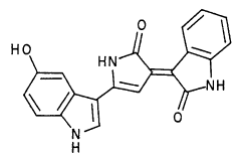

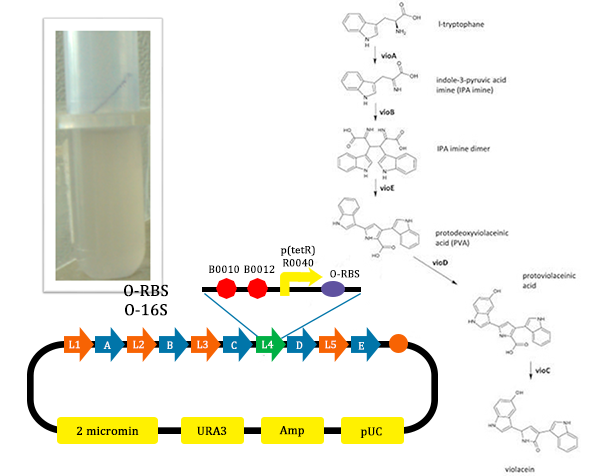

In order to verify the abilities of orthogonal system to adjust metabolism, we chose the metabolic pathway of Violacein. The reason why we chose this one are based on the facts that the pathway is suitable to adjust, and has been deeply learned.

Violacei, the major pigment produced by Chromobacterium violaceum, is a bactericide, a trypanocide, a tumoricide and in addition it has anti-viral activity.

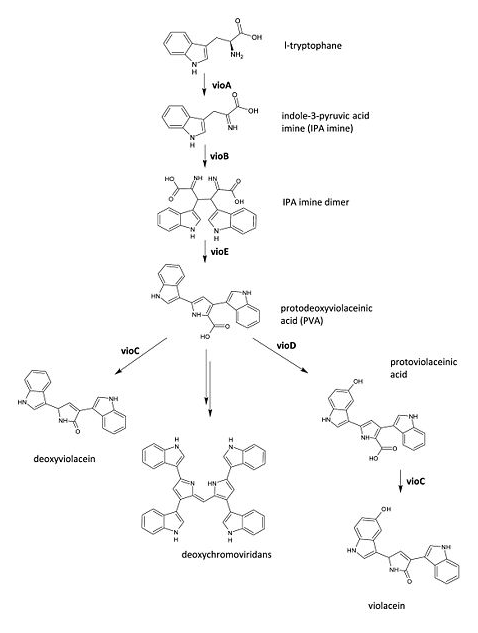

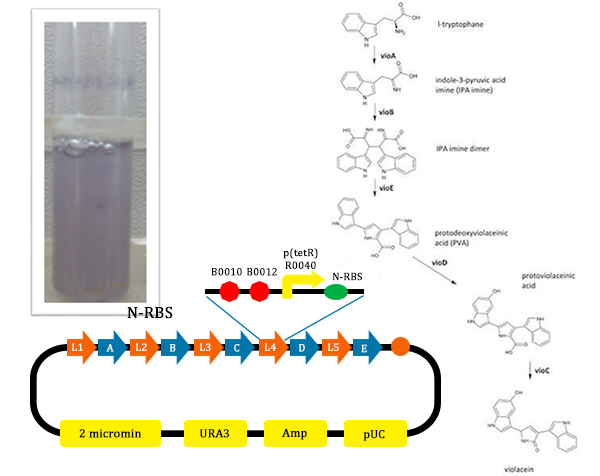

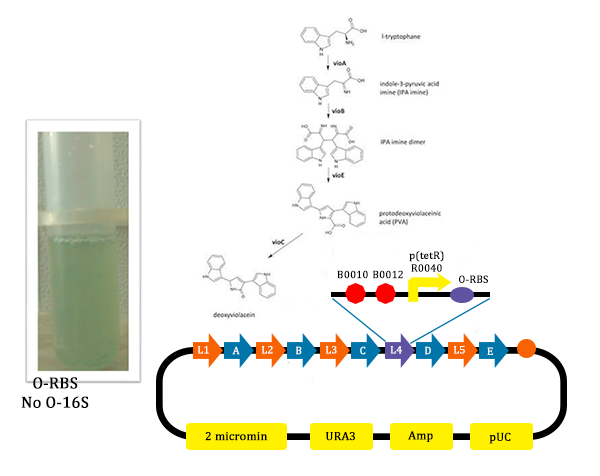

The metabolic pathways to produce Violacein are revealed in the following picture.

From the pathway, we can know that except for the desire product, Violacein, the pathway will also produce side product, deoxyviolacein.

Principle

In order to verify the feasibility of the orthogonal system in adjusting metabolism, we mutated the RBS of the gene encoding VioD by MAGE, and assembled in Yeast Assembler. The VioD gene and the O-Key gene with pBad promoter were finally transformed into the cell. Because the cell itself doesn’t have the O-Key, the gene is stringently shut down. When we added Ala to induce pBad, the O-Key were produced to open the O-Lock, so the cell could produce violacin.

Experiment

- MAGE mutate the RBS of the gene coding VioD to o-RBS

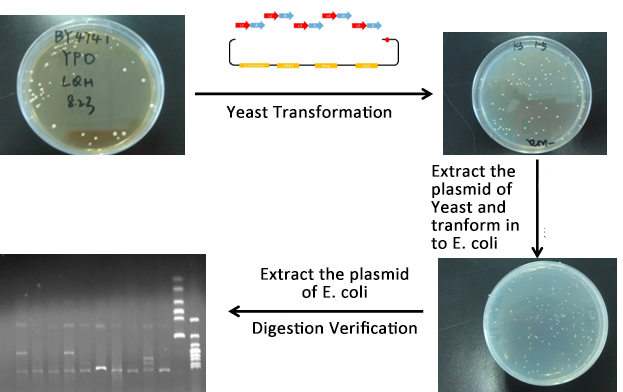

- We construct different parts of Vio operons, and transformed into yeast for assembly(In this part, we also assembly the original genes without mutation)

- Extracted the plasmid of Yeast and then transformed into our O-E.coli on LB plates.

- Verify through Cpcr and inculcated the right colony into liquid LB overnight.

- Extracted the plasmid of E.coli and verified through digestion of ligase.

Results and Analysis

- From the above picture, the process is finished smoothly and the result of Digested verification is right.

- From this picture, we could find that the test tube with the normal pathway, the liquid is purple. In such condition, for PVA have the larger potential to turn into violacein, violacein stand for a large part and liquid is purple.

- In this picture, we could find that liquid is blue. As we didn’t add Ala into the liquid, the cells didn’t produce O-ribosome, then the vioD could not be expressed. The PVA could only become deoxyviolacein, which is blue. Therefore the liquid is blue.

- In this picture, the liquid is lavender. For this tube, we added Ala, which could induce the production of O-ribosome, then PVA could turn into violacein, then the liquid is lavender.

- From the results of this experiment, we could find that the orthogonal system could work well when used to adjust metabolism, and the effect is satisfied. In the fourth part, we will further discuss the application of the orthogonal system in regulating the metabolism.

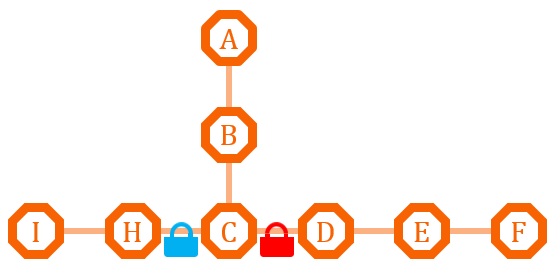

Logic Gate Metabolic Regulation

Biological logic gate has been described as the most advanced “biological circuit” ever built. This year, we used the orthogonal system to achieve metabolic regulation by logic gate – the O-Key. Our technology is a translational regulation. It not only introduce a new “AND gate” regulation to cells, but also works perfect with transcriptional regulation, waste no sequence resources and has certain potential of encryption.

The core of our O-Key consists of two part: the o-ribosome and o-mRNA. Their roles in metabolic regulation can be described as key and lock. O-ribosome serves as key, while o-mRNA is the lock. We use the o-RBS to “lock” the target sequence, and make it decipherable only under o-ribosome. They altogether forms an AND gate.

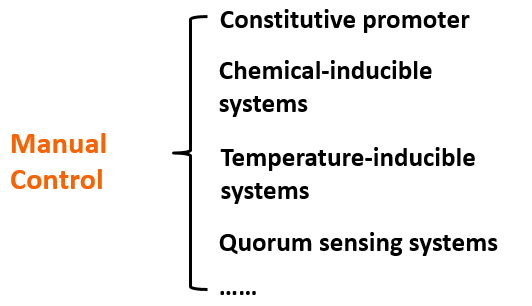

The regulation of o-ribosome can be achieved by four ways: constitutive promoter, chemical inducible systems, temperature-inducible systems, quorum sensing systems。We can chose different pathways according various conditions.

We use modeling fitting to predict the key nodes in the metabolism network. MAGE can be used to mutate the RBS of target gene to o-RBS thus locking the target gene. Compared with the conventional way of regulating by overexpression and gene knockout, our O-Key avoids decreasing cell activity and slowing growth rate because of partial adjustment of regulation networks by altering multiple cell native control transcription simultaneously. This technology saves time and boost efficiency.

We will elaborate on the function of O-Key in the following examples.

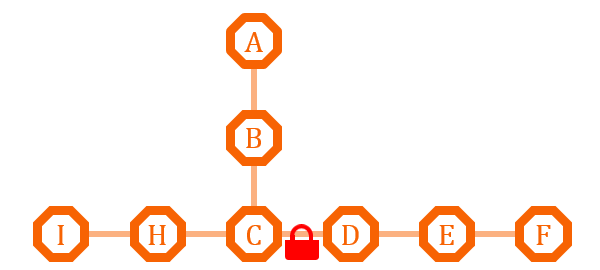

This pathway has two branches. If we put an O-Lock between C and D, we can adjust the metabolic pathway according to the cell growth cycle. Say I is the primary metabolites, and the bacteria need it for growth, we can close the O-Lock to shut down pathway D. When the bacteria is in stationary phase and in sufficient quantity, we can open the O-Lock to turn on pathway D, and increase the secondary metabolites F by its competitive advantage.

If the natural branch competitive advantage does not exist, or we need precise regulation of the metabolism of the two pathway, we can install different O-Key system on the two pathway, and use the O-Key to achieve accurate control.

In a word, the O-Key system has two advantages. On the one hand, it can achieve the same function of other complex operons using much more concise sequence.

Moreover, with the combination of different O-Key system we are able to construct more complicated logic networks using in a much simpler way. Currently, we have demonstrated that bacteria and DNA molecules can “copy” logic gate, and started constructing more complicated logic gates.

We wish this research would result in a new generation biological processor, and they have the same importance in information processing as other electric devices. Although there is still a long way before constructing a biological computer, we have the faith that our O-Key logic gate will be applied as the fundamental module in the computer.

References

- Daniel G. Gibsona, Gwynedd A. Bendersb, et al., Next-generation synthetic gene network

- Daniel G. Gibson, Synthesis of DNA fragments in yeast by one-step assembly of overlapping oligonucleotides

- Zengyi Shao, Hua Zhao1and Huimin Zhao, DNA assembler, an in vivo genetic method for rapid construction of biochemical pathways

- Lon M. Chubiz and Christopher V. Rao, Computational design of orthogonal ribosomes

- George H.McArthur IV and Stephen S. Fong, Toward Engineering Synthetic Microbial Metabolism

- Howard M Salis, Ethan A Mirsky & Christopher A Voigt, Automated design of synthetic ribosome binding sites to control protein expression

- Wenlin An and Jason W. Chinl, Synthesis of orthogonal transcriptiontranslation networks

- One-step assembly in yeast of 25 overlapping DNA fragments to form a complete synthetic Mycoplasma genitalium genome

"

"