Team:LMU-Munich/Spore Coat Proteins

From 2012.igem.org

Franzi.Duerr (Talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 162: | Line 162: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| - | <p align="justify">In fig. 6 it is noticable that the wildtype spore has hardly any fluorescence output whereas both spores with the integrated construct pSB<sub>''Bs''</ | + | <p align="justify">In fig. 6 it is noticable that the wildtype spore has hardly any fluorescence output whereas both spores with the integrated construct pSB<sub>''Bs''</sub>1C-P<sub>''cotYZ''</sub>-''cotZ''-2aa-gfp-terminator give a distinct fluorescence signal. Furthermore it is shown that the strain B 70 has the highest fluorescence intesity.</p> |

Revision as of 23:41, 26 September 2012

The LMU-Munich team is exuberantly happy about the great success at the World Championship Jamboree in Boston. Our project Beadzillus finished 4th and won the prize for the "Best Wiki" (with Slovenia) and "Best New Application Project".

[ more news ]

Sporobeads - what protein do you want to display?

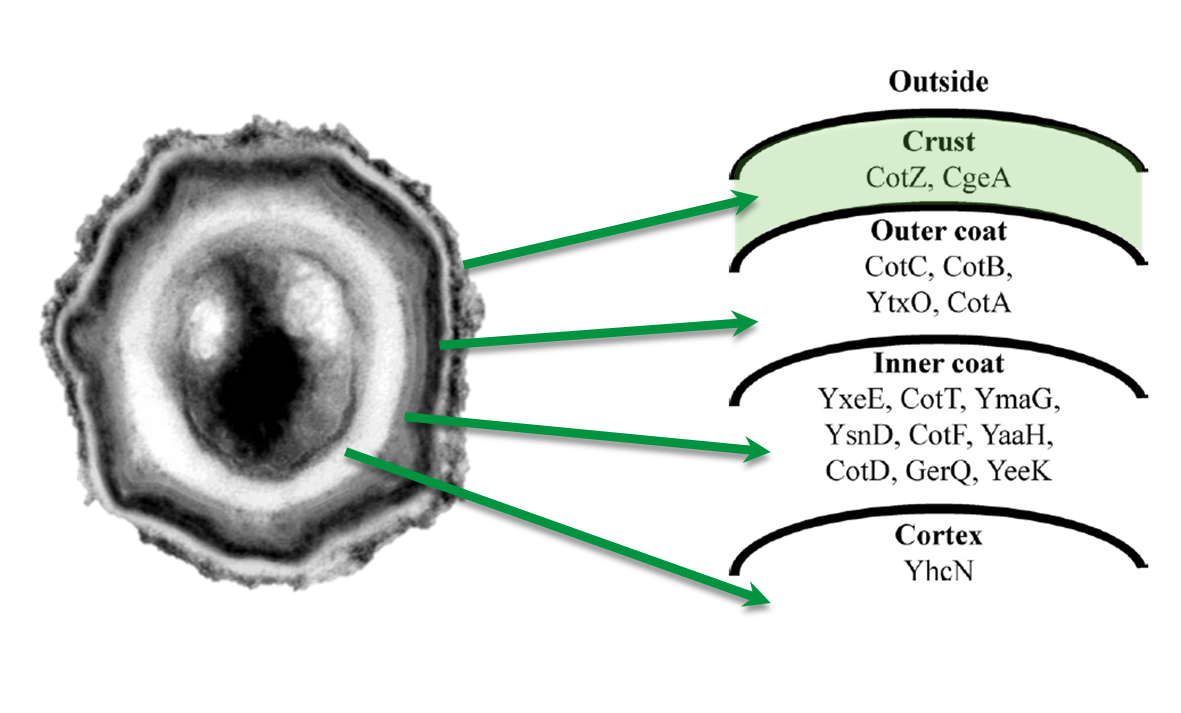

Sporobeads are Bacillus subtilis spores modulated in a way that they can be used as a platform for individual protein display. The aim of this module is to create these spores that display fusion proteins on their surface. There are several different proteins forming the spore coat layers of Bacillus subtilis spores. The outermost layer, the so called spore crust, is composed of two proteins, CotZ and CgeA ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=imamura%20et%20al.%202011%20spore%20crust Imamura et al., 2011]). This is why we used them to create functional fusion proteins to be expressed on our Sporobeads.

|

The gene cgeA is located in the cgeABCDE cluster and is regulated by its own promoter PcgeA. The cluster cotVWXYZ contains the gene cotZ which is cotranscribed with cotY and regulated by the promoter PcotYZ. Another promoter of this cluster PcotV is responsible for the transcription of the other three genes. Those three promoters were evaluated with the lux reporter genes to get an impression of their strength and their time of activation (see for more details [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K823025 pSBBs3C-luxABCDE]) so they could be used for expression of spore crust fusion proteins.

|

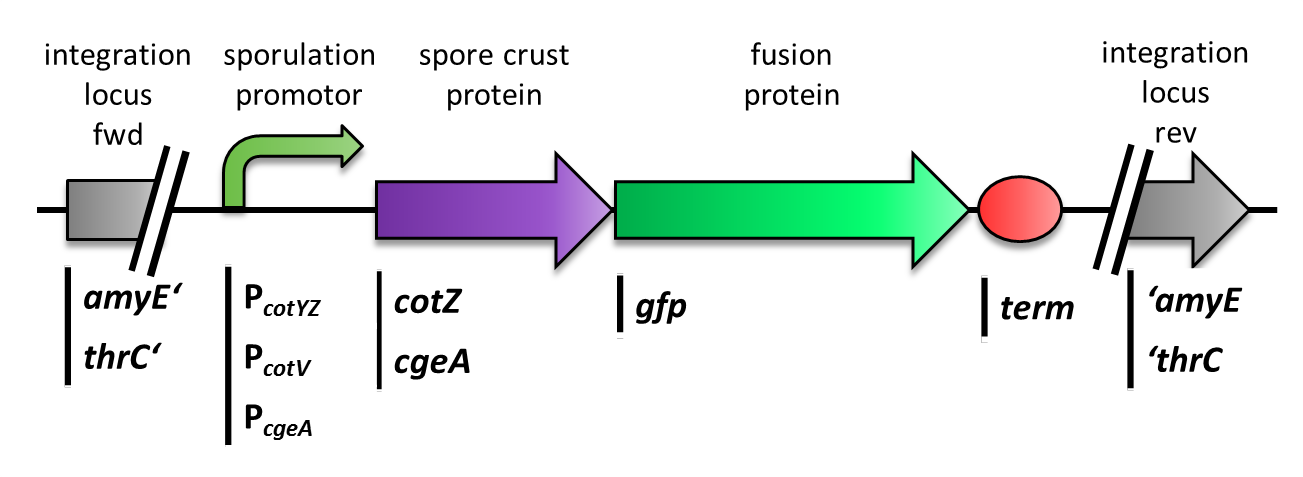

First, we used [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K823039 gfp] as a proof of principle and fused it to cgeA and [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K823031 cotZ]. This way we would determine if it is possible to display proteins on the spore crust and if their expression has any effect on spore formation.

We constructed the BioBrick for cotZ, cgeA and gfp in [http://partsregistry.org/Help:Assembly_standard_25 Freiburg Standard]. cotZwas then fused to its two native promoters, PcotV and to PcotYZ, and PcgeA, which regulates the transcription of cgeA. For cgeA we only used its native promoter PcgeA and the stronger one of the two promoters of the cotVWXYZ cluster, PcotYZ (for more details see crust promotor evaluation. While [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K823039 gfp] was ligated to the terminator B0014 (see [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_B0014 Registry]). When these constructs were finished and confirmed by sequencing, we fused them together by applying the Freiburg standard to create constructs, in which gfp is fused C-terminally to cotZ or cgeA flanked by one of the three promoters and the terminator. This way we created C-terminal fusion proteins.

But as we did not know if C- or N-terminal fusion would influence the fusion protein expression, our second aim was to construct N-terminal fusion proteins as well. For this purpose we wanted to fuse the genes for the crust proteins cotZ and cgeA to the terminator and gfp to the three chosen promoters. Unfortunately, there occured a mutation in the XbaI site during construction of gfp in Freiburg Standard. Therefore we were not able to finish these constructs.

|

| |

|

Finally we needed to clone our constructs into an empty Bacillus vector, so that they could get integrated into the genome of B. subtilis after transformation. Thus we picked the empty vector pSBBS1C from our BacillusBioBrickBox, for the cotZ constructs. This vector integrates into the amyE locus, which allows to easily check the integration via starch test. In oder to also express both crust protein constructs in one strain, the cgeA fusion proteins had to be cloned into one of our other empty vectors pSBBS4S. Unfortunately for unknown reasons, the cloning of the constructs with cgeA into this vector has so far not been successful.

We were able to finish five constructs cloned into wildtype W168 and the ΔcotZ mutant:

| recipient strain W168 | recipient strain W168 ΔcotZ (B 49) | |

|---|---|---|

| pSBBs1C-PcotYZ-cotZ-2aa-gfp-terminator | B 53 | B 70 |

| pSBBs1C-PcotYZ-cotZ-gfp-terminator | B 54 | B 71 |

| pSBBs1C-PcotV-cotZ-2aa-terminator | B 55 | B 72 |

| pSBBs1C-PcotV-cotZ-terminator | B 56 | B 73 |

| pSBBs1C-PcgeA-cotZ-2aa-terminator | B 52 | B 69 |

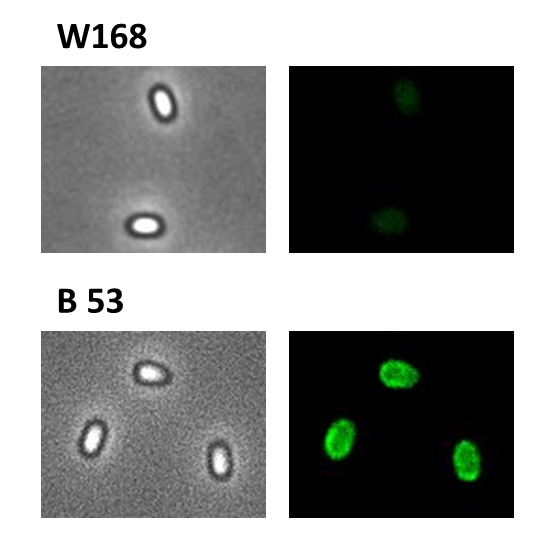

Finally, we started with the most important experiment for our GFP-Sporobeads, the fluorescence microscopy. Therefore we developed a sporulation protocol (for details see Protocol for enhancement of mature spore numbers), that increases the rates of mature spores in our mutant samples. The cells were fixed on agarose-pads and imaged in bright field and excited in blue wavelength. All Sporobeads showed green fluorescence on their surface. But B53-Sporobead (containing the PcotYZ-cotZ-gfp-terminator construct) illusidated the highest fluorescence intensity (see Figure 4). For further experiments, we chose this as it showed the brightest fluorescence.

|

Since there were still some vegetative cells left after 24 hours of growth in Difco Sporulation Medium, we wanted to purify the Sporobeads. We tried three different methods for this approach: treatment with French Press, sonification and lysozyme. By means of the microscopy results we were able to conclude that lysozyme treatment was the only successful method (see data). Additionally, it did not harm the crust fusion proteins as green fluorescence was still detectable afterwards.

Eventually, clean deletions of the native genes should reveal if there is any difference in fusion protein expression in our Sporobeads. Thus we deleted the native cotZ and cgeA using the cloning method described by [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedterm=New%20Vector%20for%20Efficient%20Allelic%20Replacement%20in%20Naturally%20Nontransformable%2C%20Low-GC-Content%2C%20Gram-Positive%20Bacteria Arnaud et al., 2004].

|

| |

|

Because of the low but distinct fluorescence of wildtype spores, we measured and compared the fluorescence intensity of 100 spores per construct (see data). The Sporobeads were investigated by fluorescence microscopy and analysed. We obtained significant differences between wildtype spores and all our Sporobeads (see Data). The intensity bar charts should thereby show the fluorescence difference between wildtype (W168), B53- and B70-Sporobeads (B53 strain with native cotZ deletion). To demonstrate the distribution of the fusion proteins we created 3D graphs, which show the fluorescence intensity spread across the spore surface. For analysis we measured the fluorescence intensity of an area of 750px per spore by using ImageJ and evaluated it with the statistical software R. The following graph (Fig. 6) shows the results of microscopy and ImageJ analysis of the strongest construct integrated into wildtype W168 (B53) and the clean deletion mutant of cotZ (B 70).

|

| |

|

In fig. 6 it is noticable that the wildtype spore has hardly any fluorescence output whereas both spores with the integrated construct pSBBs1C-PcotYZ-cotZ-2aa-gfp-terminator give a distinct fluorescence signal. Furthermore it is shown that the strain B 70 has the highest fluorescence intesity.

|

|

|

|

| Bacillus Intro | Bacillus BioBrickBox | Sporobeads | Germination STOP |

"

"