Team:Peking/Project/Luminesensor/Design

From 2012.igem.org

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| - | + | The physiologically functional domain of the novel sensor is the DNA binding domain of the LexA protein, a bacteria transcription repressor. In order to work well with our VVD photosensor domain, the DNA binding domain of the transcriptional factor must be easily discernable in the whole structure, and it had better been proven to function independent of the rest part of the protein. Of course, the DNA binding activity of the transcriptional factor we choose must be specific and rigorously require dimerization. LexA is just the transcription repressor that satisfy all these criteria. <br /><br /> | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| Line 88: | Line 81: | ||

| - | + | LexA is a transcription repressor of all the genes in the SOS system in E.coli, and its crystal structure has been resolved at high-resolution. LexA protein consists of a N-terminal DNA binding domain and a C-terminal dimerization domain with a short hydrophilic linker linking the two separate domains, making the structure impressively modular. Beside the apparent structural modularity, various researches have utilized LexA to create versatile gene expression regulating modules that have convincingly demonstrated its functional modularity, further adding to its promise. (For example, a LexA-based genetic system has been devised for monitoring and analyzing protein heterodimerization in <i>Escherichia coli</i>.) Under normal physiological conditions, two LexA proteins will form a homodimer through the dimerization domain interface and bind to the SOS box target gene sequence in promoters of genes in SOS system and create significant steric hindrance for transcription polymerase binding and thus inhibit transcription initiation. When E.coli cell encounters some extracellular factors that would cause intracellular damage, for example, DNA breakage that would result in ssDNA formation, the RecA protein, which also belongs to the SOS family, will bind to the ssDNA to form a filament and interact with LexA and cause its auto-cleavage. The cleavage will cause the DNA binding domain to dissociate from the dimerization domain. Without the help of dimerization domain, the DNA binding domain will no longer stay in its dimerized form. LexA DNA binding domain has been shown to have a thousand-fold lower binding affinity to its target sequence in its monomer form compared to its dimerized form. Thus the cleaved LexA can no longer bind efficiently to its target sequence to block the way for transcription initiation, and the target gene will be expressed. <br /><br /> | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

Revision as of 15:38, 22 October 2012

Summary

Light has created innumerable wonders in nature. Equipped with tools and methods in optogenetic research, scientists have also achieved some truly fascinating goals in a synthetic way, such as tuning the expression of genes through the intensity of light, making bacteria capable of detecting the edge of a light illuminated pattern or even recruiting fluorescent proteins to cell membrane to print patterns on the cell.

However, these fabulous achievements have not yet fully explored the potency of light as a signal. Light as a signal may carry massive information. The wavelength, intensity, frequency and spatial-temporal patterns of light are all informations encoded in a physical manner. Plus light signals possess a Bool-logic-like dynamic behavior and does not require any medium for its propagation, it would be much more enabling in transmitting accurate and complex information than the frequently investigated chemical signals. (In fact, natural biological systems has already explored this advantage to an astonishing extent. Think of our vision! )

Thus using light as a signal, we may program cellular behaviors to achieve, say, cell-cell communication that does not require physical contact. To communicate through light, first cells must be able to sense light, which means we need to develop a light sensor. And to realize this new generation of light communication that has never been implemented before, the sensor itself must make a big difference. But what kind of differences would make it better than before? In order to answer this question, we performed a brief retrospect to meditate upon what accomplishments have already been achieved, and what problems remain to be solved in optogenetic research.

Design: A Retrospect

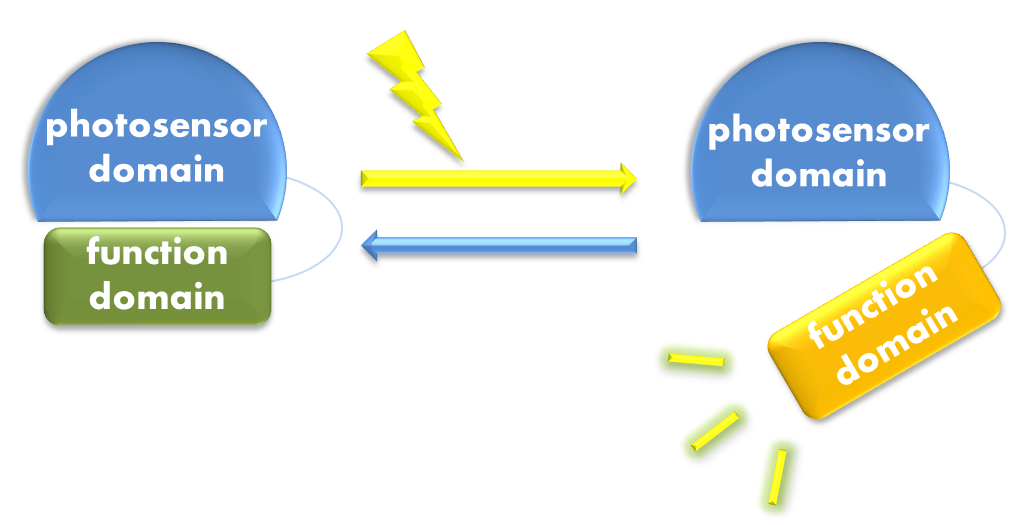

To date, virtually all of current light-sensitive optogenetic modules have been designed following two similar general principles –- attaching a physiologically functional domain to a photoreceptor domain, or rewiring physiological pathways to the downstream of the signaling pathways of photoreceptor proteins in order to use light to trigger physiological response. These two principles, whose concepts easy to understand, actually bear in their kernel the spirit of modular design which has been so strongly proposed in synthetic biology, with the former principle particularly versatile and easy to manipulate.

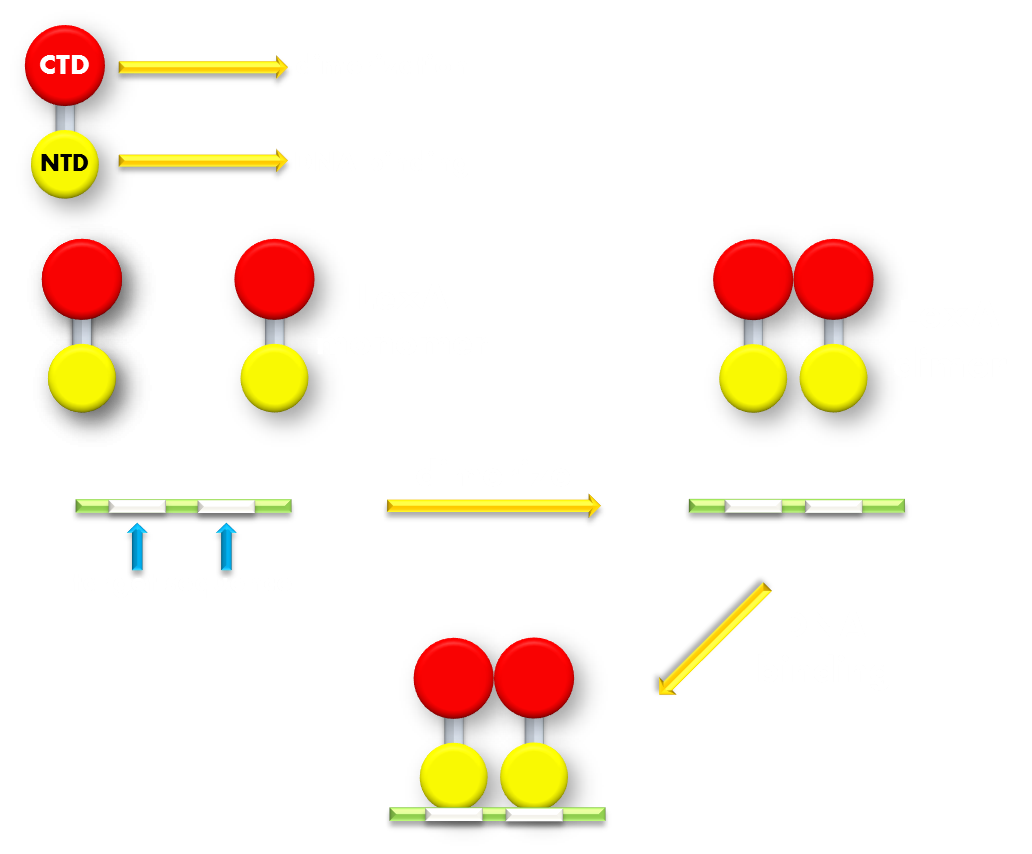

Figure 1. Illustration of the first general principle of optogenetic design. Designs of fusion proteins in optogenetic research have followed a general principle of attaching a physiological functional domain to a photosensor domain. When light excites the photosensor domain to trigger, say, confromational change, the change will be transmitted to the physiological domain to induce physiological effect.

Figure 2. Illustration of the second general principle of optogenetic design. There is another principle for optogenetic design, namely to rewire a physiological signaling pathway to the downstream of the signaling pathway of a photosensor. Thus the physiological effect of the physiological pathway may occur as a ramification of the photosensor signaling cascade.

Thus, we reasoned that the first principle is an appropriate paradigm to follow. However, in order to make the novel sensor an unprecedented success, the functional domain, photoreceptor domain, and the connection between them must be carefully chosen and sophistically designed to solve several important problems that have become gradually manifest along with the development of optogenetic research, for they may impede the future application of our optogentic tool.

First of all, in order to be widely applicable for biotechnological use, a photosensitive module must be truly ‘sensitive’. Some of the existing photosensitive modules work best around light intensity of 10W/m2, which is about the illuminance inside a room on a sunny day; some even require laser beams to activate, whose light intensity can hardly be achieved in natural environment. Apparently, the dependency on high light intensity is severely defective, because high-intensity light can be detrimental to cellular function or can even cause cell death. Moreover, this defect limits the application of optogenetics in future possible scenarios where photosensitive modules may be required to respond to soft light that is cell-and tissue-friendly, or light emitted by biological organisms, or, even more stringent, light emitted by bacteria, which is by no means brighter than the dim light of the moon. This is particularly the case when we consider cell-cell communication through light, because the cells receiving the light signal must be able to sense light emitted by another kind of cell.

Secondly, the photosensitive modules must be widely compatible. Most of current photosensitive modules have utilized light-sensitive domains of photoreceptors of eukaryotic origin, which often fail to work in prokaryotic organisms. Yet comparing to eukaryotic organisms, prokaryotic cells require significantly less stringent culturing conditions and are considerably less susceptible to environmental pollutions. What’s more, some of current photosensitive modules utilize photoreceptor domains such as phytochromes where exogenously supplied specific chormophores are necessary for its normal function. These two obvious defects substantially block the way to applying optogenetics to synthetic biology where in-field application is very much considered.

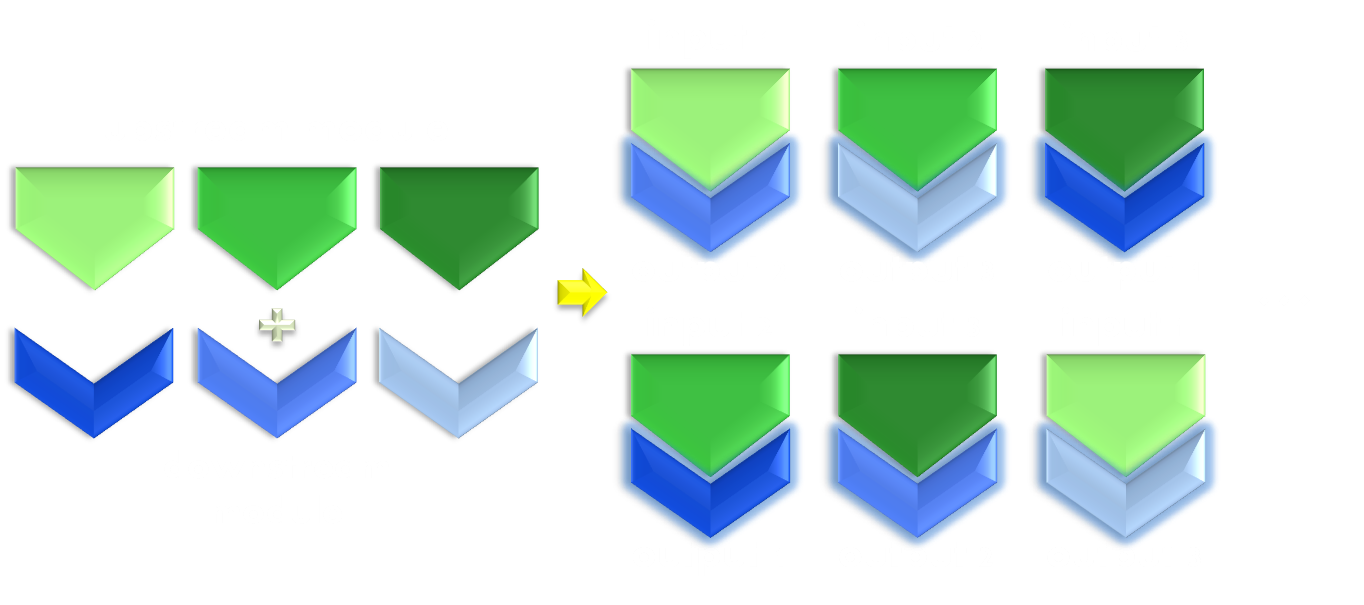

Thirdly, the design of a successful photosensitive module should be instructive to future photosensitive module engineering, which is particularly important for synthetic biology. In other words, its design should be modular enough to make possible the reshuffling of functional domain to construct modules with novel physiological functions. With not much deduction, one can easily postulate that this would require equal amount of modularity in the original photosensor domain and physiologically functional domain based on which the design was constructed.

Figure 3. Illustration of the importance of modularity. Modularity is important in both evolution and synthetic biology. As shown in the figure, even if only equipped with limited amount of modular parts, we can interchange the relationship between them to create many more new physiological function. Thus designs possessing modular components would be much more enabling than a non-modular one.

Now, with the little retrospect above, we have chosen the designing principle and determined the ‘differences’ we would like to achieve: sensitivity, compatibility, and modularity. Now comes the time to rationally build up the sensor.

Design: Building Up the Light Sensor

Under the invaluable instruction of Prof. Yi Yang, our ECUST team members constructed a brand new prokaryotic light sensor following the first principle we have described above. (Attaching a physiologically functional domain to a photosensor domain.)

The photosensor domain of the fusion protein sensor is a VVD protein. VVD is the smallest member of the phototropin photosensor family. Phototropin is one of the three most commonly used groups of photosensors (rhodopsins, phytochromes, and phototropins), and possesses the most distinct modular structure among them. Phototropins have a structurally conserved light sensor domain, termed LOV (light, oxygen and voltage) domain, which is easily discernable and often precedes, within a single reading frame, a sequence of an enzymatically functional domain, connected by the sequence of a linker domain. Despite its structural modularity, the LOV light sensitive domain also seems to possess an outstanding functional modularity, for it was found to combine with various functional domains, including naturally occurring ones and artificially synthesized ones, to perform various cellular functions.

LOV photosensor domain bears much more virtue than just its modularity. LOV domains have a non-covalently bound flavin (FMN or FAD) chromophore that is absolutely essential for its function. Unlike those choromophres of rhodopsins and phytochormes, flavin is an essential chemical compound deeply involved in the respiratory chain in all forms of life, including bacteria. In another word, in order to let this LOV domain function in bacteria, we only need to incorporate the gene into the cell, and the cell will automatically supply the protein with the chromophore. This ensures the compatibility of the sensor to a variety of biological organisms.

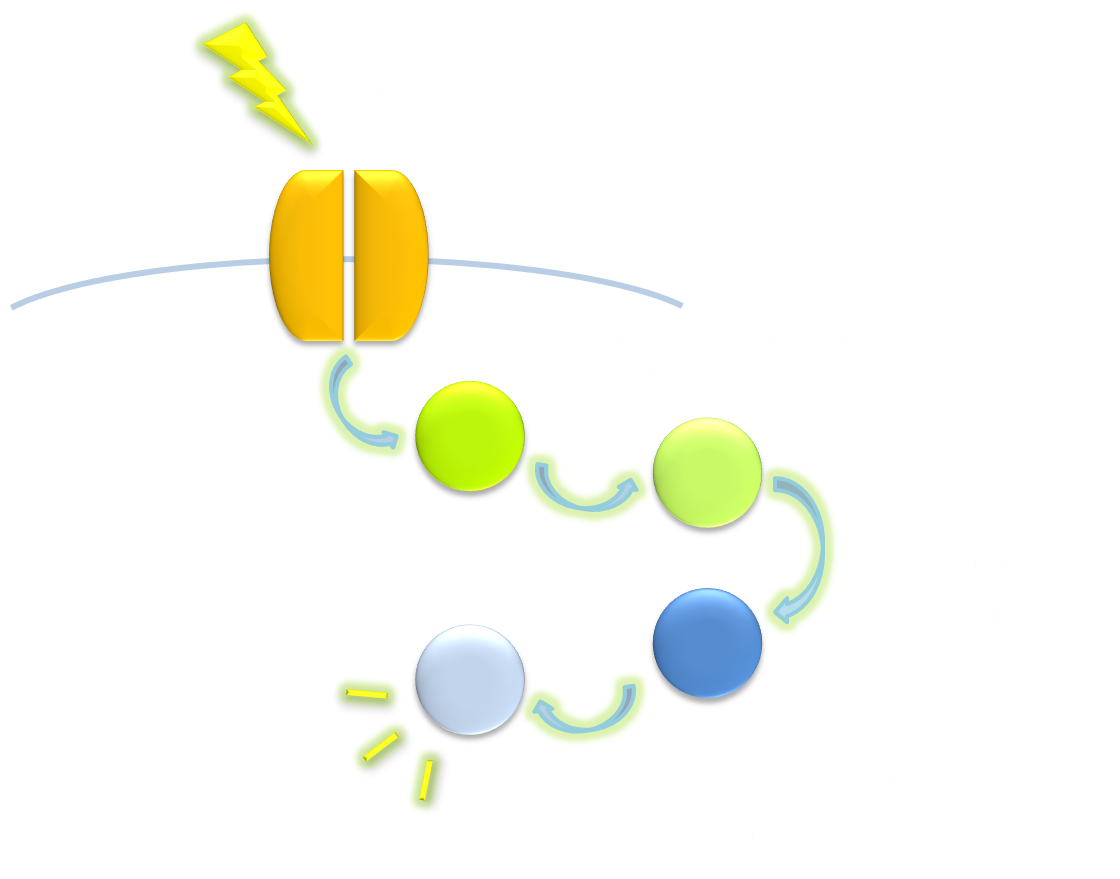

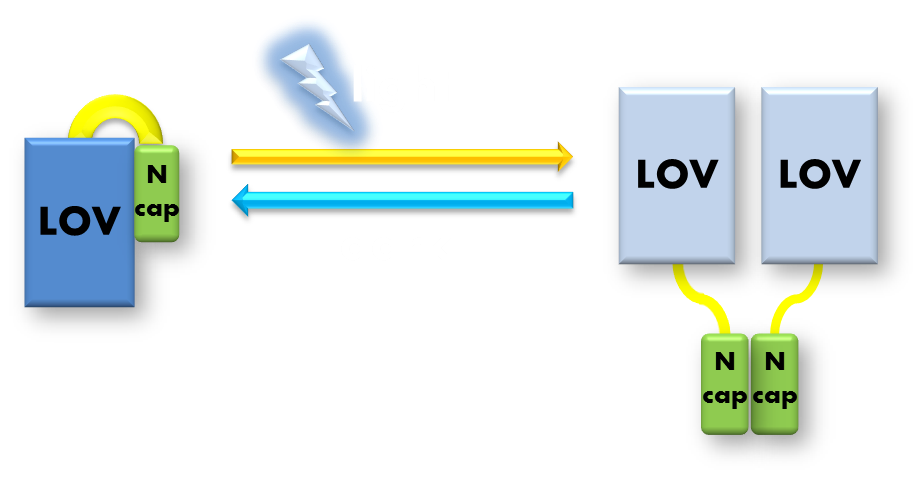

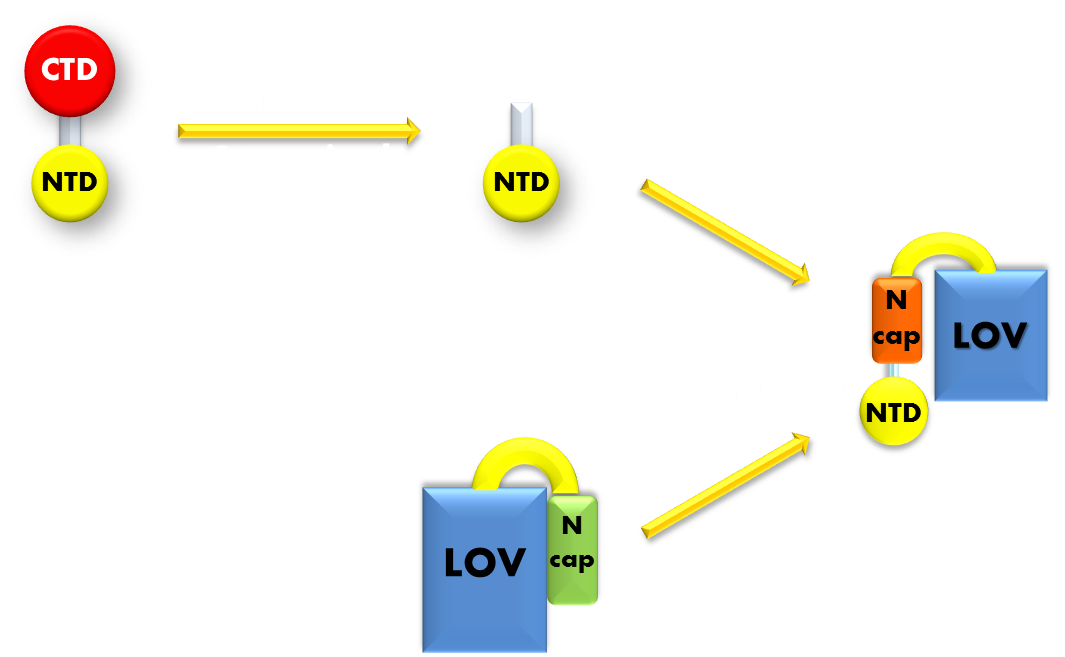

The VVD phototropin protein our team utilize is a well characterized phototropin originated from Neurospora. crassa that has been previously demonstrated to be very sensitive. VVD protein contains an N-terminal cap and a LOV photosensitive domain. When exited by blue light with wavelength of 440-480nm, a covalent bound will form between the C4 of the non-covalently bound flavin molecule and the cystine 108 residue of the LOV photosensitive domain. The formation of this covalent bound will trigger a series of conformational change in the LOV domain and cause the N-terminal cap to undock from the LOV domain. The undocked N-terminal cap will serve as an interface between VVD molecules and induce them to form rapidly exchanging dimers.

Figure 4. Illustration of function mechanism of phototropin VVD. VVD belongs to phototropin photosensor family. VVD posseses a clearly distinguishable photo-sensitive LOV domain and utilizes a FAD (flavin adenine dinucleotide) molecule as its chromophore. When excited by blue light, the N-terminal cap of VVD protein will disassociate from the LOV domain and serves as a dimerization surface for subsequent homo-dimerization. When the dimerized VVD proteins are no longer exposed to blue light, they will gradually decay back to its dark state.

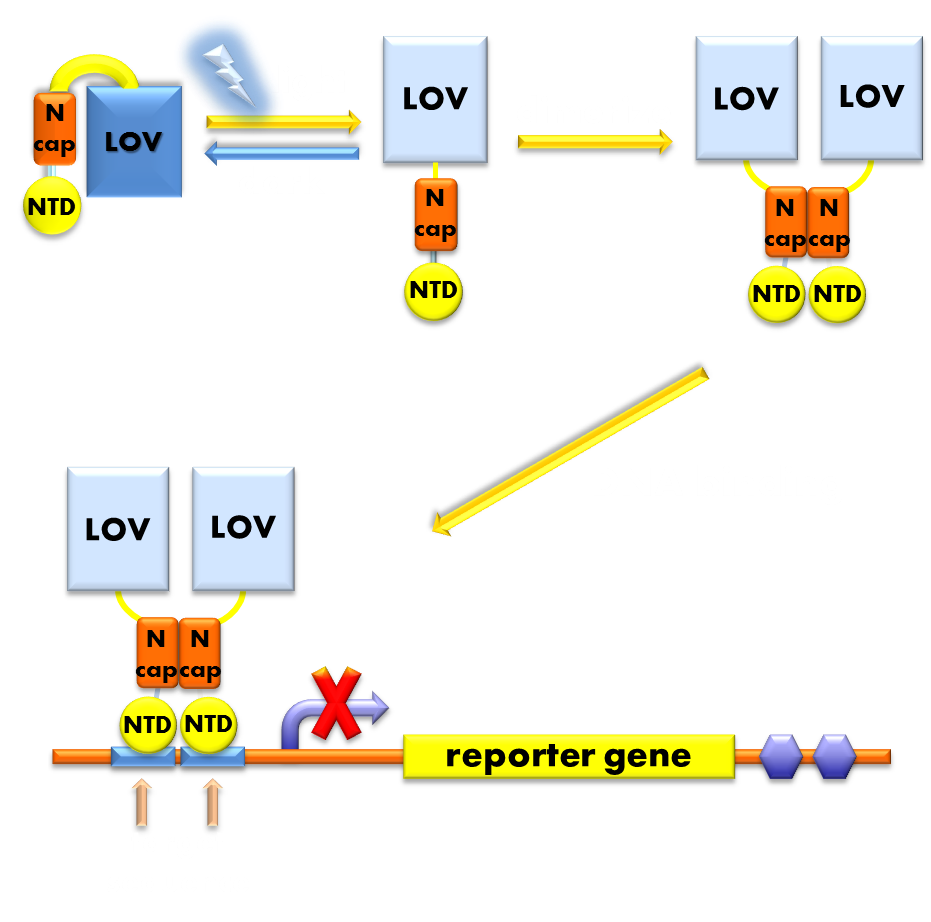

Figure 7.Illustration of function mechanism of LexA transcription repressor. LexA is the general repressor of the genes in bacteria SOS system. It is composed of a C-terminal domain (CTD), which is responsible for dimerization, and a N-terminal domain (NTD), which is responsible for DNA binding. SOS system genes possess a (some possess several) symmetrical sequence (CTGT(N)8ACAG) in their promoters, which is called the SOS box. LexA proteins will form a dimer in bacteria cell and the NTDs will recognize and bind to the SOS box in SOS promoters and thus inhibit transcription initiation.

LexA is a transcription repressor of all the genes in the SOS system in E.coli, and its crystal structure has been resolved at high-resolution. LexA protein consists of a N-terminal DNA binding domain and a C-terminal dimerization domain with a short hydrophilic linker linking the two separate domains, making the structure impressively modular. Beside the apparent structural modularity, various researches have utilized LexA to create versatile gene expression regulating modules that have convincingly demonstrated its functional modularity, further adding to its promise. (For example, a LexA-based genetic system has been devised for monitoring and analyzing protein heterodimerization in Escherichia coli.) Under normal physiological conditions, two LexA proteins will form a homodimer through the dimerization domain interface and bind to the SOS box target gene sequence in promoters of genes in SOS system and create significant steric hindrance for transcription polymerase binding and thus inhibit transcription initiation. When E.coli cell encounters some extracellular factors that would cause intracellular damage, for example, DNA breakage that would result in ssDNA formation, the RecA protein, which also belongs to the SOS family, will bind to the ssDNA to form a filament and interact with LexA and cause its auto-cleavage. The cleavage will cause the DNA binding domain to dissociate from the dimerization domain. Without the help of dimerization domain, the DNA binding domain will no longer stay in its dimerized form. LexA DNA binding domain has been shown to have a thousand-fold lower binding affinity to its target sequence in its monomer form compared to its dimerized form. Thus the cleaved LexA can no longer bind efficiently to its target sequence to block the way for transcription initiation, and the target gene will be expressed.

Figure 8. Procedure of building up our Luminesensor. We take the N-terminal domain of LexA protein, which is responsible for DNA binding, and fused it to the N-terminal of VVD photosensor protein. Thus our Luminesensor is constructed.

Figure 9. Illustration of the function mechanism of our Luminesensor. When exposed to blue light, the N-terminal cap of VVD domain will undock and cause VVD domain to dimerize. The dimerization of VVD protein will help the dimerization of N-terminal domains of LexA protien fused to the N-terminal of VVD domain. When helped to dimerize, the NTD of LexA protein will recognize and bind to the SOS box in the promoter of our reporter gene and inhibit transcription initiation.

With the discussion above, we have decided to use DNA binding domain of LexA repressor protein as the physiologically functional domain. With a flexible linker linking the two distinct domains, we now have the panorama of our design of photosensitive fusion protein. We named this VVD-LexA based photosensitive fusion protein the ‘Luminesensor’.

Design: Ensuring Orthogonality

Perhaps a careful reader has already noticed a severe defect in our design. That is, by choosing the DNA binding domain of a bacteria endogenous transcription repressor, we must use reporter genes that will also be repressed by endogenous LexA protein. If we do not introduce changes into the DNA binding domain of our Luminesensor, the only way to rule out the interference of endogenous LexA would be knocking out the genomic sequence of LexA protein. This will indubitably diminish its applicability in the future, since it will not work in any strain with endogenous LexA remaining. (For details see Modeling Luminesensor Orthogonality)

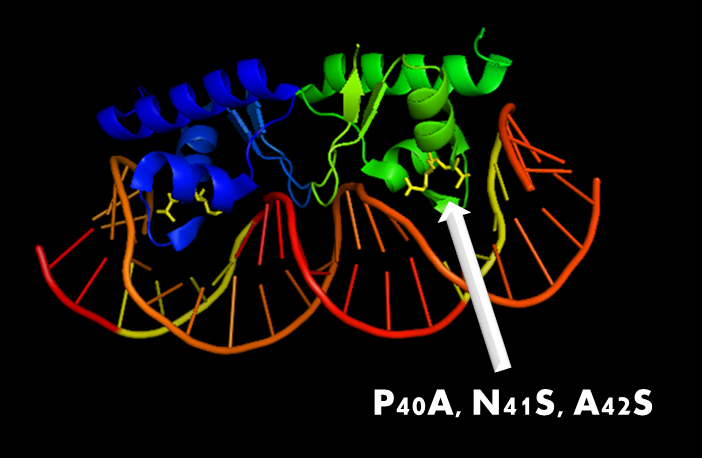

Figure 10. A molecular structure of N-terminal domain of LexA protein. The arrow points to the position of residue 40, 41 and 42. In LexA408 protein, three point mutations P40A, N41S and A42S are introduced into the N-terminal domain. These three mutations near the DNA binding surface of the protein will change its binding specificity. LexA408 will recognize a symmetrically altered sequence different from the one recognized by wild type LexA.

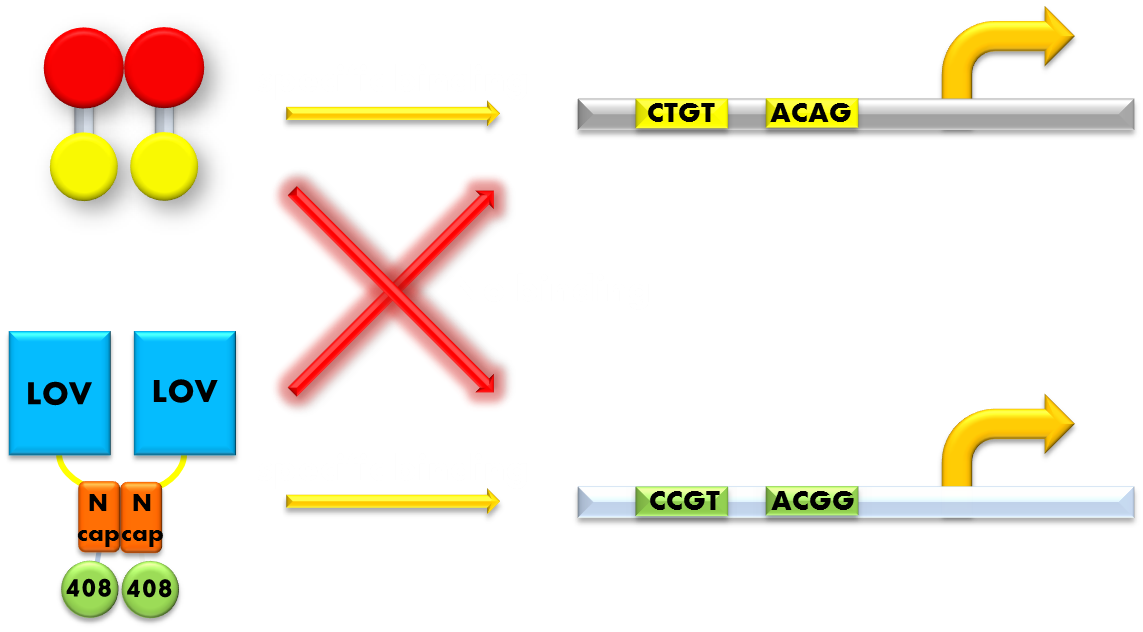

Figure 11. Our solution to the problem of orthogonality. We found that a LexA variant LexA408 will only recognize a symmetrically altered SOS box (CCGT(N)8ACGG), different form the original one (CTGT(N)8ACAG). So we changed the LexA NTD domain of our wild type Luminesensor to its 408 form, and changed the SOS box in our reporter gene promoters correspondingly. Now the endogenous LexA protein will no longer bind to the promoters of our reporter gene, while our Luminesensor still possessing the light-inducible repression function. Thus we ensured our system's orthogonality to the bacteria SOS system.

So we set out to find a solution to this important problem. The most natural way would be creating a mutated form of LexA so that it will only recognize a target sequence different from the sequence the wild-type LexA would recognize. We were happy to discover that such a thing actually exists. It is called the LexA408 variant, and it carries mutations PA40, NS41 and AS42, and has been shown to have much higher affinity for a symmetrically altered target sequence CCGT (N)8 ACGG, different from the wild type SOS box CTGT (N)8 ACAG, which is specifically recognized by the wild-type LexA. Thus, by introducing the 408 mutations into the DNA binding domain of our Luminesensor, we can insulate our light-sensitive system from the interference from the genetic context of the host strain. This outstanding characteristic ensures the orthogonality of our system to the endogenous SOS system will greatly enhance the compatibility of our module to those synthetic modules that have hitherto been designed and thus adds to the promise of future application.

Design: Dynamic Performance Optimization

Though our Luminesensor has outshined many previously designed optogenetic modules in many aspects, space still remains for its improvement. A particularly important matter would be the dynamic performance of our Luminesensor. Signal-background ratio is always a significant judging criterion in synthetic modules. The more digital-like the output may be, the more likely the module would function efficiently in a complex biological system where wanted and unwanted noises are inevitable. Though our Luminesensor has already shown a high background-signal ratio, we still deem dynamic range optimization necessary, since background-signal ratio can never be too high. Another concern would be whether the system is able to be easily reset. In our Luminesensor system, this is equivalent to saying whether our Luminesensor will be able to decay back fast to its dark state when it is no longer exposed to light. This is particularly important when our system is to be applied in a scenario where cell movement is inevitable. For example, imagine we are using liquid medium to culture our Luminesensor containing bacteria and applying to a proportion of the medium blue light to inhibit reporter gene, say GFP, expression to create some sort of pattern, cells that have received blue light will constantly swim out of the illuminated area. If our Luminesensor’s decay half-life is very long, the light-received cells will eventually distribute evenly in those dark area, so no pattern would form. Unfortunately, VVD protein, the photosensor domain we use, has a typical light-to-dark decay half-life of hours. This makes our decay half-life optimization extremely important.

In order to rationally optimize our Luminesensor’s dynamic range and decay half-life, we need to build a dynamic model in the first place to simulate our Luminesensor system and determine which ones of those parameters in the system would be decisive to the two dynamic features we are interested in. (For details see Modeling Luminesensor)

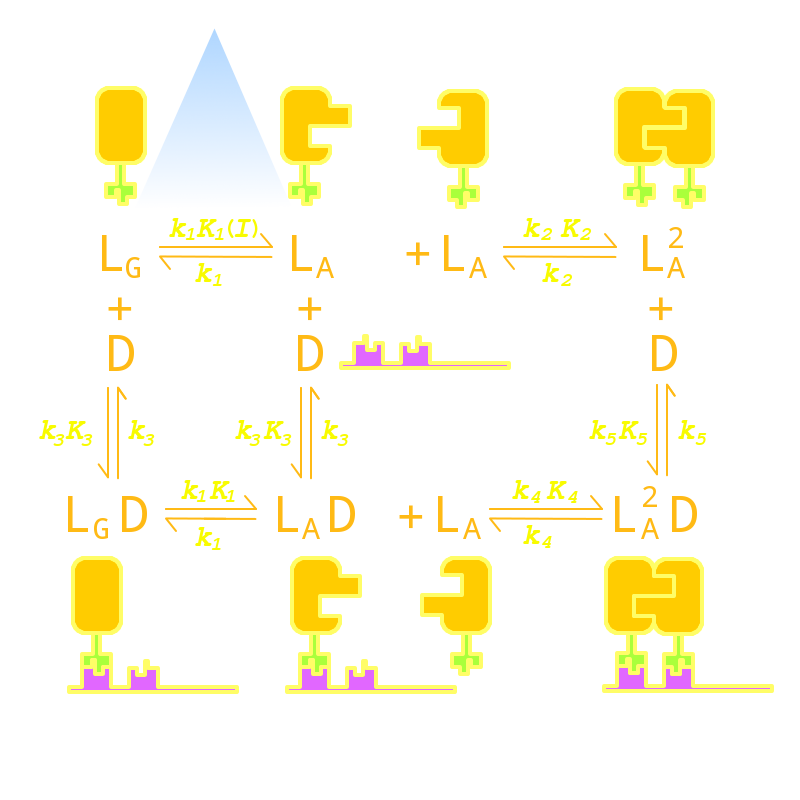

We listed all possible states of the molecules involved in our Luminesensor system and transitions between those states and created an ordinary differential equation system based on law of mass action to describe the dynamic behavior of our system. After in-silico simulation, we singled out 4 critical parameters in our system that would determine the above two aspects of our system’s dynamic performance.

Figure 12. Kinetic Network of our Luminesensor system. This figure shows all possible states of our Luminesensor reporter gene system and all possible reactions that will lead to interconversion between these states. All parameters are marked on their corresponding position.

Figure 13. Ordinary differential equations describing the kinetic behavior of our Luminesensor system. All the ordinary differential equations were built based on the kinetic network above.

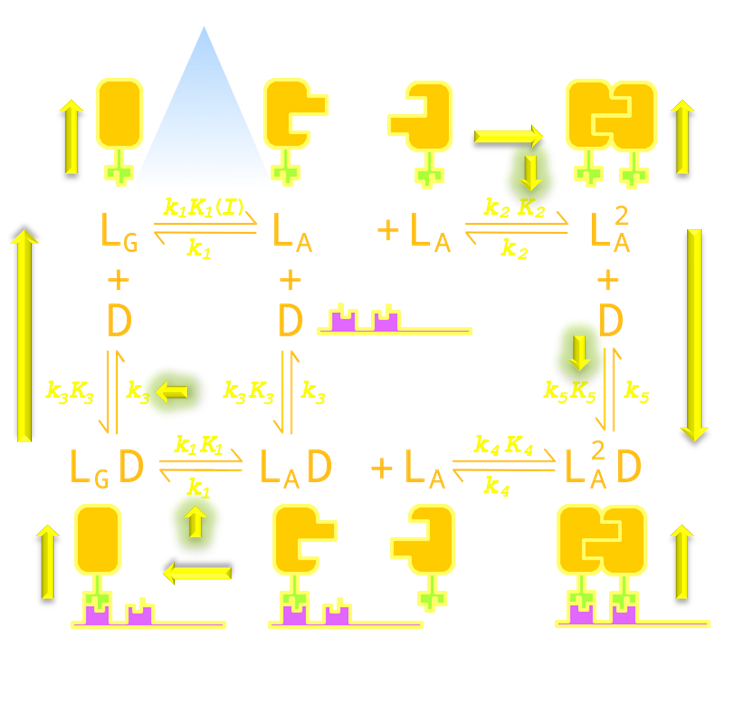

Two of them will affect the background-signal ratio, namely the VVD protein dimerization equilibrium constant and dimerized Luminesensor’s DNA binding equilibrium constant. This is easy to understand intuitively. Because the tighter the Luminesensors dimerizes when illuminated by light, the greater the intracellular concentration of the dimerized Luminesensor will be. The more tightly the dimerized Luminesensors binds the target DNA sequence, the greater proportion of the target gene will be repressed, thus reducing the background of reporter gene expression under light.

The other two parameters are responsible for the decay half-life, namely the rate constant of VVD photosensor domain’s decaying from the light-state back to its dark-state and rate constant of monomer luminesenor’s disassociating form target DNA sequence. This is also easy to understand intuitively. The faster the VVD proteins decay back to its dark-state, the faster the Luminesensor will turn from it dimerized form to its monomer form, which is significantly less efficient in binding target DNA sequence. Thus, the faster the monomer Luminesensors disassociates from the target sequence, the faster the steric hindrance to RNA polymerase created by the DNA-bound Luminesensors will be lifted, thus reducing the amount of time required for the system to reset. (For details see Modeling Luminesensor Simulation)

Figure 14. An intuitive understanding of the importance of parameter K2 (Luminesensor dimerization equilibrium constant), K5 (Luminesensor dimer DNA binding equilibrium constant), k1 (VVD domain decay rate constant) and k3 (Luminesensor monomer DNA disassociation rate constant). As described in the text, K2 increment will push equilibrium towards the Luminesensor dimerization, and K5 increment will push equilibrium towards dimerized Luminesensor's DNA binding, thus reducing reporter gene expression background under light. Similarly, k1 and k3 will accelarate dissociation of monomer the Luminesensor from DNA and dark-state Luminesensor formation, thus precipitating system reset.

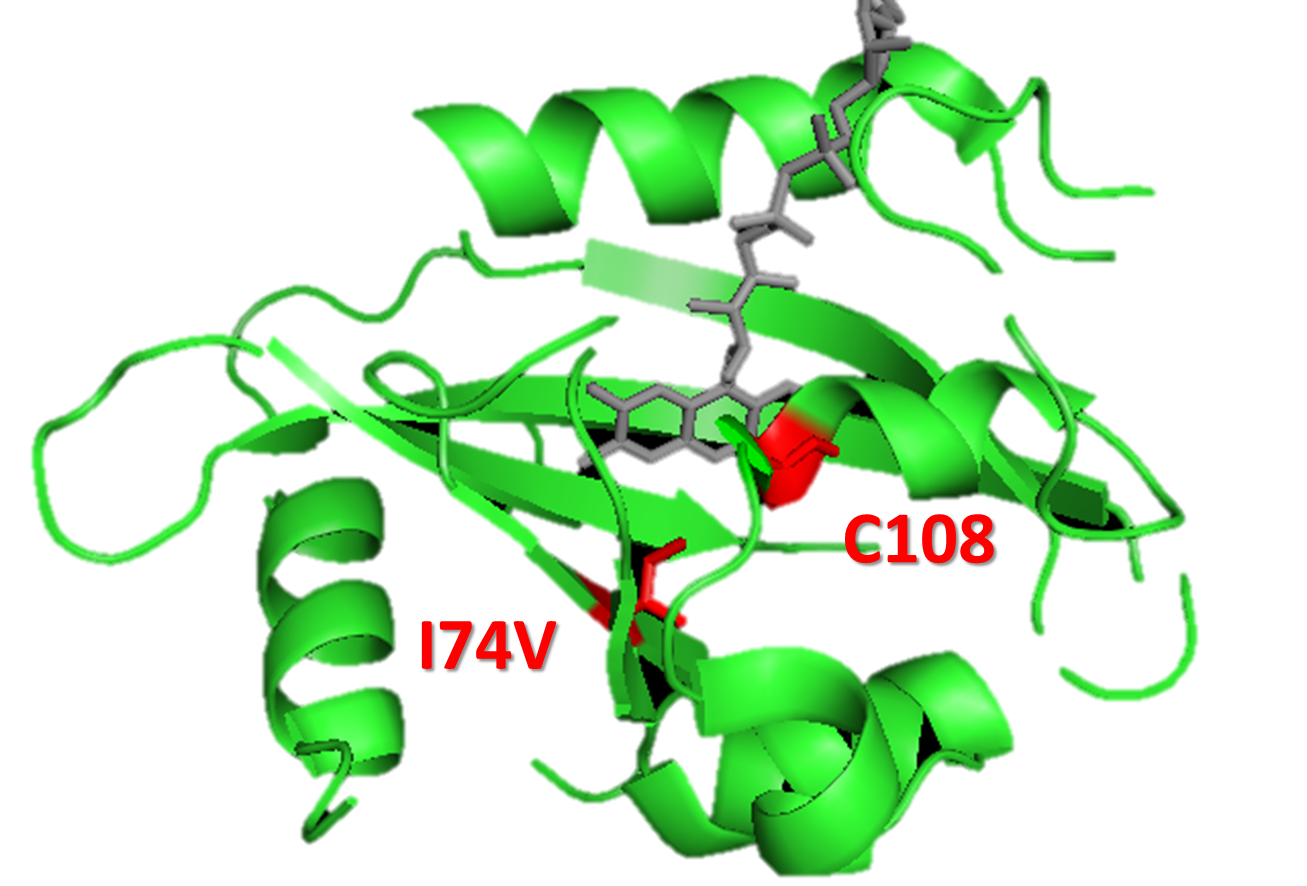

Having singled out these four critical parameters, we set out to search through literature to find mutations that would enhance them. We discovered that there were not very many existing mutations that would enhance the dimerized Luminesensor’s DNA binding equilibrium constant. Rather, these mutations seem to undermine the DNA binding affinity, which would be detrimental to our system. We further reasoned that any mutation that would facilitate the disassociation of the monomer-form Luminesensors from the target DNA sequence is also likely to undermine the DNA binding affinity. Therefore, we focused on looking for the VVD photosensor domain mutations that would promote VVD dimerization and VVD decay. We eventually localized on two specific mutations of VVD photosensor domain: a M135I mutation that will enhance the VVD dimerization, and a I74V mutation in the vicinity of FAD molecule that will enhance the VVD decay rate. (For details see Modeling Luminesensor Optimization)

Figure 15. A molecular structure of VVD protein marking the position of residue 74. As shown in the figure, residue 74 (originaly isoleucine) resides in the vicinity of FAD (flavin adenine dinucleotide) molecule (the chromophore of VVD protein) and residue cystine 108. When VVD is excited by light, a covalent bound will form between residue cystine 108 and C4 of FAD, leading to VVD's conformational change to its light-state. The mutation I74V will interact with Cystine 108 and FAD molecule to destablize the adduct form, accelarating VVD's decay back to its dark-state.

Figure 16. A molecular structure of the VVD protein marking the position of residue 135. As shown in the figure, residu 135(originally methionine) also resides near the FAD molecule. M135I is proposed to change the electronic environment of FAD molecule and somehow enhance VVD dimerization (possibly by stablizing light-state). The exact molecule mechanism is unclear.

Having determined the plausible mutations, when then introduced mutation M135I, I74V and the combination of the two mutations into our 408 form of the Luminesensor. By characterizing the dynamic behavior of the mutated Luminesensor along time course, we discovered that mutation M135I indeed improved the signal-background ratio significantly. However, I74V mutation seems to reduce the signal-background ratio dramatically, rendering our Luminesensor useless. So disregarding of the faster decay half-life it may provide, we have to rule I74V out of our design.

Reference

- 1. Shimizu-Sato, S., Huq, E., Tepperman, J.M., & Quail, P.H.(2002). A light-switchable gene promoter system. Nat. Biotechnol. 20: 1041: 1044

- 2. Wu, Y., Frey, D., Lungu, O.I., Jaehrig, A., Schlichting, I., Kuhlman, B. & Hahn, K.M.(2009). A genetically encoded photoactivatable Rac controls the motility of living cells. Nature, 461: 104: 8

- 3. Levskaya, A., Weiner, O.D., Lim, W.A. & Voigt, C.A.(2009). Spatiotemporal control of cell signalling using a light-switchable protein interaction. Nature, 461: 997: 1001

- 4.Möglich, A., Ayers, R.A. & Moffat, K.(2009). Design and Signaling Mechanism of Light-Regulated Histidine Kinases. J. Mol. Biol., 385: 1433: 1444

- 5. Strickland, D., Moffat, K. & Sosnick, T.R.(2008). Light-activated DNA binding in a designed allosteric protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 105: 10709: 10714

- 6. Ohlendorf, R., Vidavski, R.R., Eldar, A., Moffat, K. & Möglich, A.(2012). From Dusk till Dawn: One-Plasmid Systems for Light-Regulated Gene Expression. J. Mol. Biol., 416: 534: 542

- 7. Toettcher, J.E., Voigt, C.A., Weiner, O.D. & Lim, W.A.(2010). The promise of optogenetics in cell biology: interrogating molecular circuits in space and time. Nat. Methods, 8: 35: 38

- 8. Bacchus, W. & Fussenegger, M.(2011) The use of light for engineered control and reprogramming of cellular functions. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol., 23: 1: 8

- 9. Cole, S.T.(1983) Charaeterisation of the Promoter for the LexA Regulated sulA Gene of Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet., 189: 400: 404

- 10. Crane, B.R. et al.(2007) Conformational Switching in the Fungal Light Sensor Vivid. Science, 316: 1054: 1057

- 11. Herrou, J. and Crosson, S.(2011) Function, structure and mechanism of bacterial photosensory LOV proteins. Nat. Rev. Microbiol., 9: 713: 723

- 12. Zoltowski, B.D., and Crane, B.R.(2008) Light activation of the LOV protein Vivid generates a rapidly exchanging dimer. Biochemistry, 47: 7012: 7019

- 13. Zoltowski, B.D., Vaccaro, B. & Crane, B.R. Mechanism-based tuning of a LOV domain photoreceptor. Nat. Chem. Biol., 5: 827: 834

- 14. Vaidya, A.T., Chen, C.H., Dunlap, J.C., Loros, J.J., and Crane, B.R.(2011) Structure of a light-activated LOV protein dimer that regulates transcription in Neurospora crassa. Sci. Signal., 4: ra50

- 15. Wang, X., Chen, X. & Yang, Y.(2012) spatiotemporal control of gene expression by a light-switchable transgene system. Nat. Methods, 9: 266: 269

- 16. Zhang, A.P.P., Pigli, Y.Z & Rice, P.A.(2010) Structure of the LexA–DNA complex and implications for SOS box measurement.Nature, 466: 883: 886

- 17. Butalaa, M., Zgur-Bertokb, D., and Busby, S. J. W.(2009) The bacterial LexA transcriptional repressor. Cell. Mol. Life Sci., 66: 82: 93

- 18. Tabor, J.J., Salis,H.M., Simpson, Z.B., Chevalier,A.A., Levskaya, A., Marcotte, E.A., Voigt, C.A., and Ellington, A.D.(2009) A Synthetic Genetic Edge Detection Program. Cell, 137: 1272: 1281

- 19. Voigt., C.A., et al.(2005) Engineering Escherichia coli to see light. Nature, 438: 441: 442

- 20. Ye, H., Baba, M.D.E., Peng, R., Fussenegger, M.(2011) A Synthetic Optogenetic Transcription Device Enhances Blood-Glucose Homeostasis in Mice. Science, 332: 1565: 1568

"

"