Team:Minnesota/Project/UV Absorption

From 2012.igem.org

(Difference between revisions)

m |

|||

| (22 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 132: | Line 132: | ||

<div id="MainBoxContent" style="background-color:white;"> | <div id="MainBoxContent" style="background-color:white;"> | ||

| - | <div style="position:absolute;top:0px;margin-left:50px; width:600px; height:450px; overflow-y:scroll; text-align:left;"> <!---START HERE---> | + | <div style="position:absolute;top:0px;margin-left:50px; width:600px; height:450px; overflow-y:scroll; text-align:left;overflow-x:hidden;"> <!---START HERE---> |

<h1>Synthesizing UV-Protective Compounds in Bacteria</h1><br> | <h1>Synthesizing UV-Protective Compounds in Bacteria</h1><br> | ||

| - | Our first idea was to engineer the production of the Micosprine-like Amino Acids (MAAs) in <i>E. coli</i>. These compounds confer UV protection in Anabaena variabilis and are currently used in sunscreen that protects against the entire UVA and UVB spectrum. To obtain these compounds for use in industry, the current method is direct extraction from A. variabilis. To develop an alternate way of producing these compounds, genes coding for enzymes in their production pathways were taken from A. variabilis and cloned into <i>E. coli</i> using BioBrickTM techniques. The result: E. coli that can produce UV protectant compounds, which has several implications. E. coli are cheap, easy to produce, grow quickly, are preferred for use in industry, and can be grown up in giant bioreactors. Therefore the speed and ease at which MAA-producing bacteria can be grown, as well as the amount that can be grown would drastically increase. Additionally, promoters and mechanisms of down-regulation in <i>E. coli</i> are well characterized, making modification and control of the pathway much simpler. These parts could easily be employed in future experiments where increased UV tolerance is desired (for example, in the characterization of a UV-sensitive promoter). Alternatively, a skin-based, UV-protectant probiotic could eventually be developed if these parts are incorporated into a native, non-pathogenic skim bacterium chassis, such as <i>Staphylococcus epidermidis</i>. Imagine a “sunscreen” that grows naturally on your skin!< | + | <p>Our first idea was to engineer the production of the Micosprine-like Amino Acids (MAAs) in <i>E. coli</i>. These compounds confer UV protection in Anabaena variabilis and are currently used in sunscreen that protects against the entire UVA and UVB spectrum. To obtain these compounds for use in industry, the current method is direct extraction from A. variabilis. To develop an alternate way of producing these compounds, genes coding for enzymes in their production pathways were taken from A. variabilis and cloned into <i>E. coli</i> using BioBrickTM techniques. The result: E. coli that can produce UV protectant compounds, which has several implications. E. coli are cheap, easy to produce, grow quickly, are preferred for use in industry, and can be grown up in giant bioreactors. Therefore the speed and ease at which MAA-producing bacteria can be grown, as well as the amount that can be grown would drastically increase. Additionally, promoters and mechanisms of down-regulation in <i>E. coli</i> are well characterized, making modification and control of the pathway much simpler. These parts could easily be employed in future experiments where increased UV tolerance is desired (for example, in the characterization of a UV-sensitive promoter). Alternatively, a skin-based, UV-protectant probiotic could eventually be developed if these parts are incorporated into a native, non-pathogenic skim bacterium chassis, such as <i>Staphylococcus epidermidis</i>. Imagine a “sunscreen” that grows naturally on your skin!</p> |

| - | + | <p><b>Goal</b><br> | |

| - | <p><b>Goal | + | Clone multiple gene pathways from algal species into <i>E. coli</i> to produce natural UV-protective sunscreening compounds.</p> |

| + | <p><b>Background</b><br> | ||

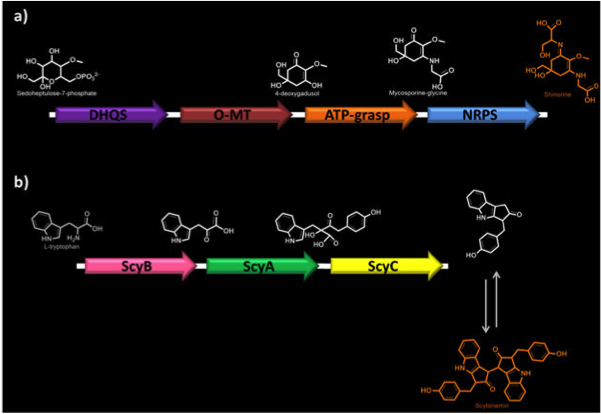

| + | Our research has focused on two novel biosynthetic pathways found in two distinct algal species. A pathway ending in the production of two UV-protective compounds, shinorine and mycosporine-glycine, was cloned from <i>Anabaena varibalis</i>. A second pathway leading to the production of the unrelated UV-screening compound scytonemin was cloned from <i>Nostoc punctiforme</i>. Our objective is to develop novel and effective production platforms for these compounds, some of which are currently used in expensive sunscreens and lotions. These compounds are used both for the UV-absorptive properties as well as their role as potent antioxidants.</p> | ||

| - | < | + | <img src="http://i1158.photobucket.com/albums/p607/iGEM_MN/1Bac.png"> |

| + | <p><b>Figure 1. Biosynthetic pathways of MAAs.</b> a) Shinorine biosynthesis. DHQS, dehydroquinate synthase; O-MT, O-methyltransferase; ATP-grasp; NRPS, non-ribosomal peptide synthase. b) Scytonemin biosynthesis. ScyA (NpR1276), acetolactate synthetase; ScyB (NpR1275), leucine dehydrogenase; ScyC (NpR1274), protein of unknown function.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p><b>Methods</b><br> | ||

| + | <p>Genomic DNA was obtained from the Brett Barney Lab (University of Minnesota) and ATCC for <i> A. variabilis</i> and <i>N. punctiforme</i>, respectively. From here, PCR primer extension was used to clone each individual gene (seven in total) with flanking restriction digest sites to be used for vector cloning. Each gene was cloned into an individual pUCBB BioBrick™ cloning vectors. From here, genes from each individual pathway were cloned onto one pUCBB BioBrick™ vector for each specific pathway.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Upon successful cloning of each pathway, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was used to analyze production of mycosporine-glycine, shinorine, and scytonemin. Methods for extraction and analysis of these compounds from liquid E. coli cultures have previously been developed by Balskus and Walsh (2011).</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Additionally, UV-sensitivity screens were performed on E. coli cultures expressing target pathways. A preliminary screen was done using different exposure time points (t=5, 10, 15, 20 minutes) and dilutions. A secondary test was performed with a 104 fold dilution and an exposure time of 20 minutes. Treated cells were plated and then CFUs were counted.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p><b>Parts List</b><br> | ||

| + | BBa_K814000 dehydroquinate synthase (DHQS) generator <br> | ||

| + | BBa_K814001 ATP-grasp (ATPG) generator <br> | ||

| + | BBa_K814002 dehydroquinate O-methyltrasferase (O-MT) generator <br> | ||

| + | BBa_K814003 shinorine non-ribosomal peptide synthase (NRPS) generator <br> | ||

| + | BBa_K814004 mycosporine-glycine biosynthetic pathway <br> | ||

| + | BBa_K814005 shinorine biosynthetic pathway <br> | ||

| + | BBa_K814006 negative control for mycosporine-like amino acid biosynthesis <br> | ||

| + | BBa_K814007 ScyA (acetolactate synthase) generator <br> | ||

| + | BBa_K814008 ScyB (leucine dehydrogenase) generator <br> | ||

| + | BBa_K814009 ScyC generator <br> | ||

| + | BBa_K814010 partial scytonemin biosynthetic pathway, scyCB <br> | ||

| + | BBa_K814011 scytonemin biosynthetic pathway, scyBAC <br></p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p><b>Results</b><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="http://i1158.photobucket.com/albums/p607/iGEM_MN/2_Bac.png"> | ||

| + | |||

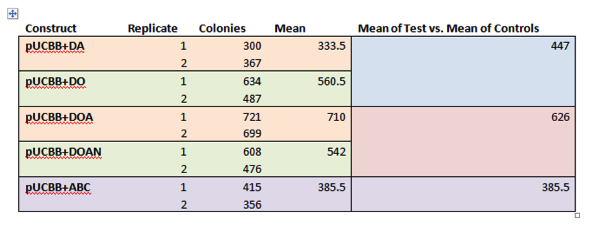

| + | <p><b>Figure 2. HPLC analysis of E. coli expressing MAA biosynthetic genes.</b> Cell extracts of E. coli transformed with +DOA (DHQS, O-methyl transferase, and ATP-grasp) and +DOAN (DOA, and NRPS) showed production and 4-deoxygadusol (a) and mycosporine-glycine (b). Shinorine was not detected in the +DOAN expressing cells. Samples were compared against a +DA negative control (this construct lacks the ability to produce the 4-deoxygadusol intermediate). Cells expressing +ABC (ScyA, ScyB, ScyC) did not show scytonemin production. Data was compared with previous results from Balskus and Walsh, as a standard could not be obtained. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="http://i1158.photobucket.com/albums/p607/iGEM_MN/3Bac.png"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p><b>Figure 3. UV sensitivity screens of E. coli cultures producing MAAs.</b> Preliminary results for the secondary screen showed increased survival in cells producing mycosporine-glycine when compared with +DO and +DA negative controls. Cells expressing +ABC did not show increased survivability.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <img src="http://i1158.photobucket.com/albums/p607/iGEM_MN/cellimages.jpg"> | ||

| + | |||

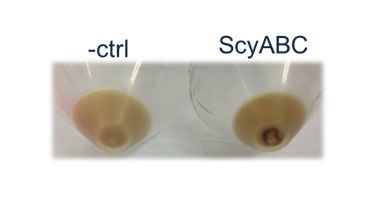

| + | <p><b>Figure 4. Visual inspection of E. coli cells containing the scytonemin pathway.</b> Although HPLC and growth tests were negative, cells expressing +ABC were seen to be expressing a deep brown product that could easily be visualized (below). The control is a cell culture expressing a +DA plasmid vector. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p><b>Conclusion</b><br> | ||

| + | Successful transformation and expression of the mycosporine-glycine/shinorine pathway was achieved, and production of mycosporine-glycine was observed via HPLC analysis. This appears to incur resistance to UV-radiation to a certain degree. As we move forward, it will become critical to obtain expression of NRPS, the final gene in this pathway, and production of shinorine. Steps are being taken to optimize of this final step in the biosynthetic pathway is ongoing.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Although conclusive evidence regarding the production of scytonemin was not found, the initial results are promising. Previous studies on algae described a deep brown secretion in cells that were shown to be producing this compound. This pathway has not yet been fully characterized, and additional genes with unknown functions are present within the native <i>N. punctiforme</i> gene cluster. We are currently looking into cloning and expressing these additional genes, and looking for ways to isolate and analyze potential intermediate products within this pathway.</p> | ||

<!---END--> | <!---END--> | ||

Latest revision as of 03:58, 4 October 2012

Like us on FB and follow us on Twitter!

"

"