Team:Calgary/Project/OSCAR/Bioreactor

From 2012.igem.org

Emily Hicks (Talk | contribs) |

|||

| (55 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2012/9/9d/UCalgary2012_OSCAR_Bioreactor_Low-Res.png" style="float:right; max-width: 200px; padding: 10px;"></img> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2012/9/9d/UCalgary2012_OSCAR_Bioreactor_Low-Res.png" style="float:right; max-width: 200px; padding: 10px;"></img> | ||

<h2>Introduction</h2> | <h2>Introduction</h2> | ||

| - | <p> | + | <p>We want to use the genetically engineered bacteria of the OSCAR project to convert toxic organic compounds into recoverable hydrocarbons. To accomplish this goal our team has designed a contained bioreactor system to operate in the locations of oil sands tailings ponds and oil refineries. We used what is known of similarly sized bioreactors and hydrocarbon recovery techniques to decide what factors to consider in the design of OSCAR's home: culture conditions, method for hydrocarbon extraction, and containment of the genetically modified organisms. |

| - | + | </p> | |

| - | + | ||

<h2>Research</h2> | <h2>Research</h2> | ||

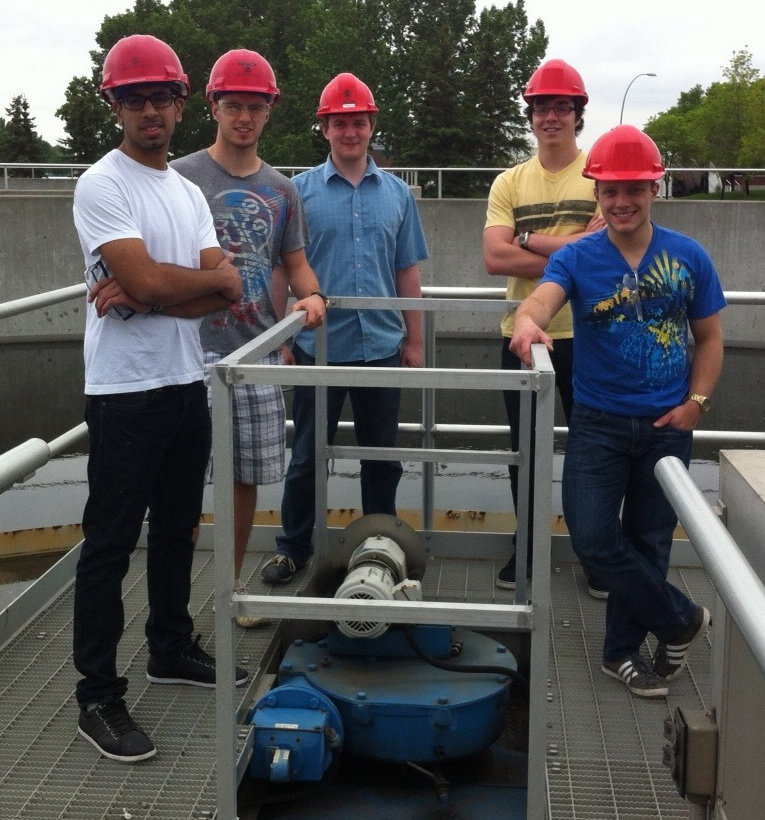

| - | </html>[[File:Wastewater plant-ucalgary.JPG|thumb|200px|right| | + | </html>[[File:Wastewater plant-ucalgary.JPG|thumb|200px|right|Figure 1: Visiting Calgary's Bonneybrook wastewater treatment plant, overlooking one of the bioreactors. ]]<html> |

| - | <p>Before diving into | + | <p>Before diving into making a bioreactor, we first had to research current solutions in the field. To help us with this phase, we read papers on bioreactors that exist with such diverse applications as wastewater treatment, tissue engineering and beer fermentation. |

| + | To observe a large scale bioreactor, we toured a wastewater treatment plant (we would have preferred a brewery) where we interviewed plant managers and learned conditions that need to be considered in big systems: open or closed system (theirs was open), methods for oxygenation and preventing contents from settling. We also interviewed graduate students and professors doing research on bioreactors at the University of Calgary for their insight as well as meeting weekly with the supervisors and biologists on our team. Here is a picture from our trip to the wastewater plant!</p> | ||

| + | |||

<h2>Our Bioreactor Evolution</h2> | <h2>Our Bioreactor Evolution</h2> | ||

| - | <p>Throughout the summer we worked on creating a prototype of the bioreactor. | + | <p>Throughout the summer we worked on creating a prototype of the bioreactor. The process that was deemed most suitable was a cross between a fed-batch system and a continuous stir method in a closed system, where the reactors would be continually fed with more bacterial nutrients and fresh tailings. To remove the hydrocarbons from the culture we decided to use a belt skimmer, similar to those used to help clean up oil spills. This method allows us to run the belt to pick up hydrocarbons without having to remove the entire solution of the batch. This way the bacterial culture already present in the tank can be maintained in active culture to continuously produce more hydrocarbons, which is favored for an industrial scale (1000+ L tanks). Tailings are pre-filtered to prevent environmental strains from joining the mix. Additionally, the process would have to occur within an enclosed system to ensure its containment.</p> |

| - | < | + | <p>To make sure that the belt does not transfer live bacteria into the hydrocarbon collection tank, we will have a UV light aimed at the most apical point in the belt path to ensure that any bacteria picked up by the skimmer receive a lethal dose of radiation just before the hydrocarbons are removed from the bioreactor chamber.</p> |

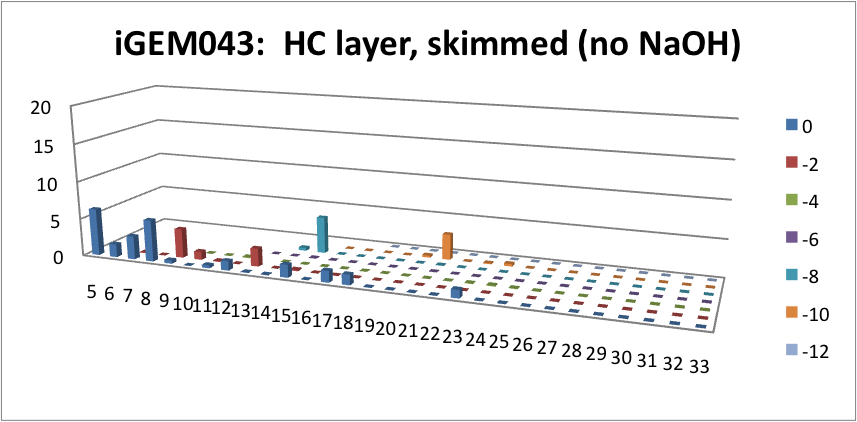

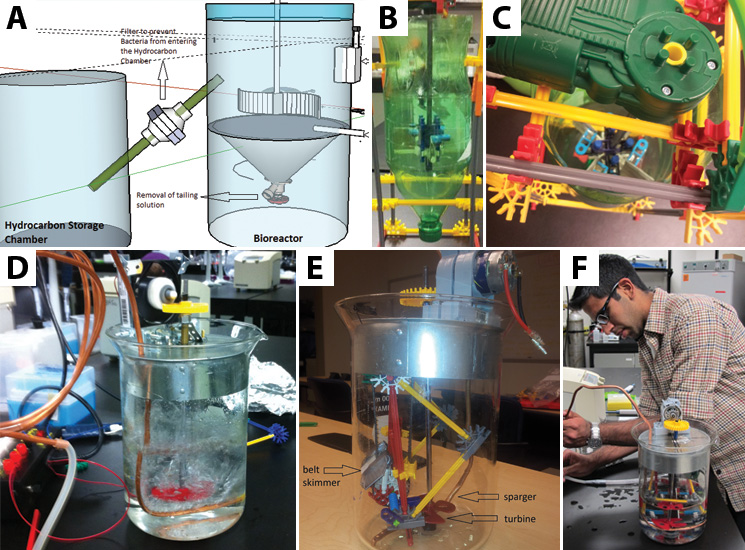

| - | + | </html>[[File:UCalgary2012_BioreactorOverview.jpg|thumb|745px|left|Figure 2: From computer to prototype: how we made our bioreactor. a) Our system began with a model built using Google Sketch Up. It had two chambers and a tube acting as a siphon to pull off hydrocarbons. b/c) The first prototype took shape using materials we found in the lab (including the recycling bin). This system was meant to show that the bioreactor could agitate a solution with the turbine. d) This prototype is the first manufactured design we put together. It needs a power source to turn on the computer fan motor which runs the turbine. It also includes an air sparger system to allow our system to be oxygenated. Apart from the plastic gears, it is fully autoclavable. e/f) Our final prototype, which includes the belt skimmer in an enclosed system. It is able to skim off the top oil layer in a solution of water and canola oil into a small falcon tube.]]<html> | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| + | <h2>The Prototype Design</h2> | ||

| + | <p>We determined the essential concepts that needed to be developed in the prototype. As with the scaled up design, we included the belt skimmer, powered by a small motor to move the belt into and out of the system. Since our bioreactor would necessarily have live cells, our prototype operated as a completely closed system to prevent cross contamination with microbes outside the chamber. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h2>The Belt Skimmer in Action</h2> | ||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<iframe width="600" height="338" align="center" src="http://www.youtube.com/embed/DVTR68DMi5U" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe> | <iframe width="600" height="338" align="center" src="http://www.youtube.com/embed/DVTR68DMi5U" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | <p> This video showcase our belt skimmer. The model hydrocarbons stick to the belt shown in the video and are skimmed off into a Tim Horton's coffee cup (the only disposable cup we could find in the lab. </p> | ||

| - | < | + | <h2>Current Prototype with both the Sparger and Turbine</h2> |

| - | + | ||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<iframe width="338" height="600" align="center" src="http://www.youtube.com/embed/4onfIfuQJ9c" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe> | <iframe width="338" height="600" align="center" src="http://www.youtube.com/embed/4onfIfuQJ9c" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | <p> The second video shows our bioreactor prototype in action with both the sparger and turbine running. </p> | ||

| - | <p>Once we had these designs in place, we were able to start building models and presentation material. One of our goals was to have a computer animation of our design in motion. We were able to meet this goal by using | + | <h2>Belt Skimmer with a Collection Chamber</h2> |

| + | <div align="center"> | ||

| + | <iframe width="420" height="315" src="http://www.youtube.com/embed/HtcgPG3reH4" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <p> This video shows the collection chamber we added to the bioreactor. There is a hole at the bottom of the chamber so that during the bioreactors' showcase the model hydrocarbons don't accumulate in the chamber. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Once we had these designs in place, we were able to start building models and presentation material. One of our goals was to have a computer animation of our design in motion. We were able to meet this goal by using the Maya and RealFlow programs. Maya is a complex and extremely versatile computer animation program used in many animated movies, including James Cameron’s “Avatar”. RealFlow is a particle-generating program, used primarily for creating fluid flow and fluid effects. Combining both of these programs, we created a seventeen second long video showing the basic idea of how our bioreactor will work. Our model will be brought to the competition for demonstration purposes.</p> | ||

<h2>Particle Simulation Using RealFlow2012</h2> | <h2>Particle Simulation Using RealFlow2012</h2> | ||

| Line 53: | Line 63: | ||

<h2>Testing and Results</h2> | <h2>Testing and Results</h2> | ||

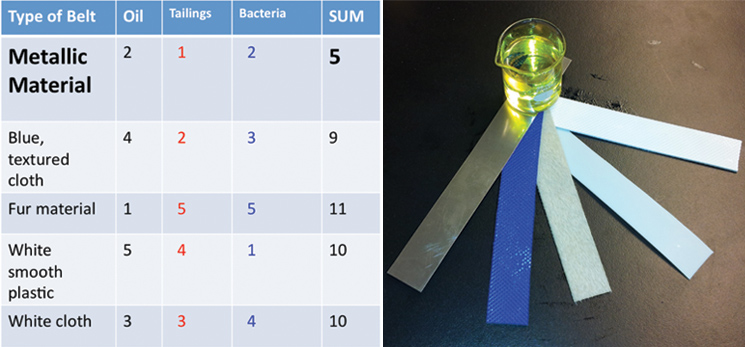

| - | <p>Using the physical models that we made, we were able to conduct experiments to help determine what will make our design most efficient. We received five different belt samples from a belt skimming company (Abanaki), | + | <p>Using the physical models that we made, we were able to conduct experiments to help determine what will make our design most efficient. We received five different belt samples from a belt skimming company (Abanaki), and conducted three different tests to determine which belt is most suitable for us. Our tests sought to find the belt that picked up the most oil, least tailing pond material, and least amount of bacteria. </p> |

| - | </html>[[File:UCalgary-Bioreactor-Materials.jpg|thumb|745px|left| | + | </html>[[File:UCalgary-Bioreactor-Materials.jpg|thumb|745px|left|Figure 3: Left panel: Belt rankings from three different tests. We tested the ability of the belts to pick up hydrocarbons, and to exclude bacteria or tailings pond water. Right panel: The five belts we tested and a sample of canola oil used for hydrocarbon pick up. From left to right: metallic material, blue texture, fur belt, white plastic, white texture]]<html> |

| + | |||

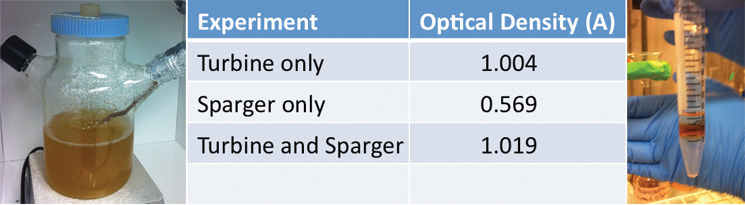

| + | <p>Additionally, we ran three different twenty-four hour bacterial growth tests in our tank to determine the effectiveness of the agitator and sparger on bacterial growth. The turbine mixes the solution so as to prevent the settling of bacterial cells and other heavier materials and to ensure even nutrient and reactant distribution in the tank. The sparger aerates the solution, which is necessary for aerobic bacteria to thrive. When assembled together, the turbine is located above the sparger thus breaking each bubble from the sparger into smaller ones. The test was conducted with a turbine and a sparger, a turbine only, and a sparger only. At the end of each experiment we measured the optical density of the solution with a spectrophotometer to quantify the bacterial growth. Operating our bioreactor with both a turbine and sparger resulted in slightly greater bacterial growth than just the turbine, which coincides with our hypothesis. In order to use the air sparger, we decided to use a HEPA filter to screen air coming out of the system to maintain constant pressure in the tank. The results are displayed below:</p> | ||

| - | < | + | </html>[[Image:UCalgary-Bioreactor-ODNA.jpg|thumb|745px|left|Figure 4: This is the spinner flask and sparger system we used for our bacterial growth tests. Each bacterial growth experiment lasted 24 hours in an incubator at 37 degrees Celsius. This is our data for the optical density reading of each bacterial growth experiment. As expected, we had the most growth when both the turbine and sparger were in operation for 24 hours. This image shows NA and Hydrocarbon Separation in a falcon tube after sitting for 5 minutes. As can be seen, a hydrocarbon layer forms on top of the naphthenic acid layer. This was a very encouraging result since we want to skim the hydrocarbon products from the top layer of our bioreactor.]]<html> |

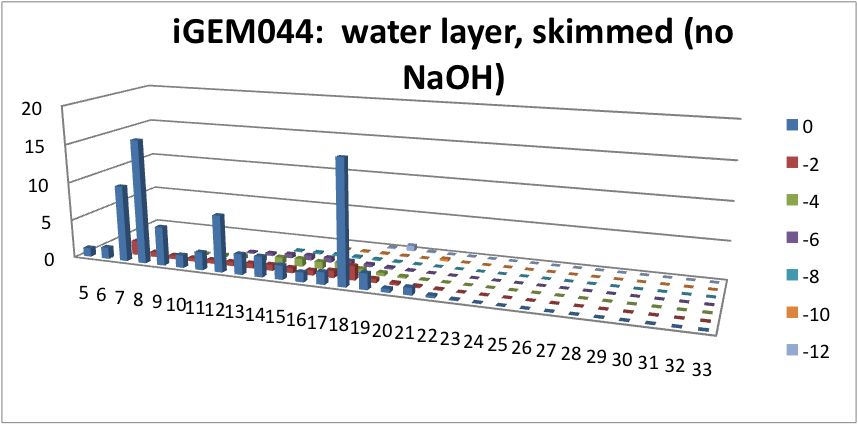

| - | </html>[[ | + | <p> Furthermore, we tested our belts' ability to pick up hydrocarbons in a solution of water and commercial naphthenic acid. We dipped our belt in a solution of hexadecane, water and naphthenic acid, then removed and scraped the picked up solution into a separate beaker. This sample was then run through GC-MS to analyze the concentration of naphthenic acid found in our skimmed solution. This is an important test since we do not want to be removing too many NAs before they have the chance to be converted to hydrocarbons. Our first tests were involved using the fur material belt. The results of the GC-MS were very promising. Since we used commercial NAs, many different types of NAs were represented in our original solution. To find the concentration of each NA, the number of carbons and rings for each type of NA are counted. As can be seen below, the figures show plots of the number of carbons and rings of each NA found in the water layer and hydrocarbon layer of our skimmed solution. Based on the size of the bars on the graph, our data shows that a higher abundance of NA were found to be associated with the water and not the hydrocarbon layer. This data suggests that minimal NAs were found in our skimmed hydrocarbon layer and that most were left in the water layer. |

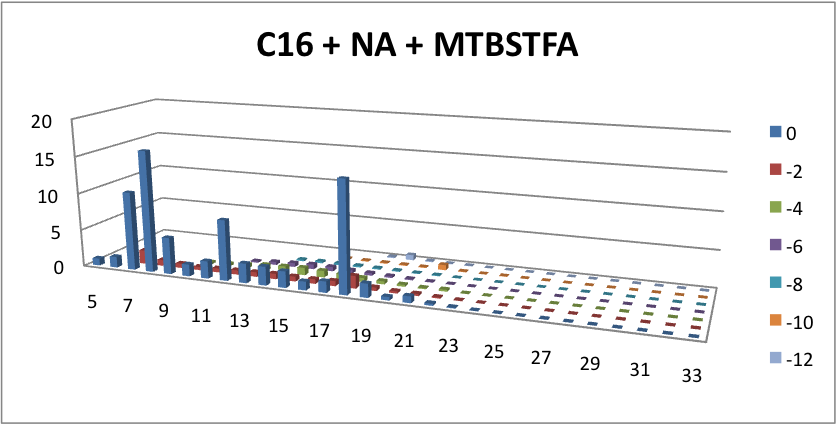

| + | </html>[[File:HC layer, skimmed (no NaOH)-ucalgary.png|thumb|600px|center|Figure 5: This graph shows the amount of NAs found in the skimmed hydrocarbon layer. The x-axis represents the carbon number, the y-axis is the % abundance of each compound, and the z-axis is the ring number of the NAs. Clearly, minimal NAs were skimmed into the hydrocarbon layer.]]<html> | ||

| + | </html>[[File:Water layer, skimmed-ucalgary.png|thumb|600px|centre|Figure 6: This graph shows how many NAs were left in the water layer of our skimmed solution. The x-axis represents the carbon number, the y-axis is the % abundance of each compound, and the z-axis is the ring number of the NAs. This data suggests that minimal amounts of NA were skimmed into our solution, and with most of those skimmed found in the water layer.]] <html> | ||

| + | <p> We also conducted these tests with our preferred belt made of metallic material. The results below show the amount of each type of naphthenic acid found in the hydrocarbon layer of our skimmed solution. As can be seen, the use of this belt also resulted in the removal of very few naphthenic acids. However, the amount of naphthenic acids removed using the metallic belt was almost the same if not greater than the amount of naphthenic acid removed by the fur material belt. Based on our previous experiments (shown in Figure 3), we expected the metallic belt to pick up far fewer naphthenic acids than the fur material belt. Although this data could potentially sway our preferred belt choice, the metallic belt still picked up much fewer bacteria which is very important when analyzing the safety of our design.</p> | ||

| + | </html>[[File:Metallic Belt NA-Hydrocarbon test-ucalgary.png|thumb|600px|center|Figure 7: This graph shows how many NAs were present in our skimmed solution using the metallic material belt. The x-axis represents the carbon number, the y-axis is the % abundance of each compound, and the z-axis is the ring number of the NAs.]]<html> | ||

| - | |||

<h2>The Final System</h2> | <h2>The Final System</h2> | ||

| + | <p>Along with physical considerations of the containment unit, we must also consider the composition and growth of the bacteria in the reactor. Each OSCAR bacterium would have the most suitable kill-switch circuit attached to its respective hydrocarbon conversion circuit. The bacterium would also have a deletion of a gene for the biosynthesis of glycine. Glycine would be supplemented in our defined production media, but cells would not survive outside of the bioreactor where glycine is absent. We envision OSCAR to be a co-culture of decarboxylation, decatecholization, denitrogenation, and desulfurization. Lastly, due to the energetically expensive nature of maintaining the circuits, we anticipate that if the circuits are constitutively produced cell growth rate may be very slow. Therefore in the final circuits we may want them to be activated by quorum sensing promoter systems. Essentially, when cells are at low density they focus energy on growth; when cells reach appropriate density for the reaction chamber, transcription of the circuit is enabled. Together we hope that the system will clean up recalcitrant petroleum waste and produce energy. | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

</html> | </html> | ||

}} | }} | ||

Latest revision as of 02:51, 27 October 2012

[http://www.example.com link title]

Hello! iGEM Calgary's wiki functions best with Javascript enabled, especially for mobile devices. We recommend that you enable Javascript on your device for the best wiki-viewing experience. Thanks!

Bioreactor: The House of OSCAR

Introduction

We want to use the genetically engineered bacteria of the OSCAR project to convert toxic organic compounds into recoverable hydrocarbons. To accomplish this goal our team has designed a contained bioreactor system to operate in the locations of oil sands tailings ponds and oil refineries. We used what is known of similarly sized bioreactors and hydrocarbon recovery techniques to decide what factors to consider in the design of OSCAR's home: culture conditions, method for hydrocarbon extraction, and containment of the genetically modified organisms.

Research

Before diving into making a bioreactor, we first had to research current solutions in the field. To help us with this phase, we read papers on bioreactors that exist with such diverse applications as wastewater treatment, tissue engineering and beer fermentation. To observe a large scale bioreactor, we toured a wastewater treatment plant (we would have preferred a brewery) where we interviewed plant managers and learned conditions that need to be considered in big systems: open or closed system (theirs was open), methods for oxygenation and preventing contents from settling. We also interviewed graduate students and professors doing research on bioreactors at the University of Calgary for their insight as well as meeting weekly with the supervisors and biologists on our team. Here is a picture from our trip to the wastewater plant!

Our Bioreactor Evolution

Throughout the summer we worked on creating a prototype of the bioreactor. The process that was deemed most suitable was a cross between a fed-batch system and a continuous stir method in a closed system, where the reactors would be continually fed with more bacterial nutrients and fresh tailings. To remove the hydrocarbons from the culture we decided to use a belt skimmer, similar to those used to help clean up oil spills. This method allows us to run the belt to pick up hydrocarbons without having to remove the entire solution of the batch. This way the bacterial culture already present in the tank can be maintained in active culture to continuously produce more hydrocarbons, which is favored for an industrial scale (1000+ L tanks). Tailings are pre-filtered to prevent environmental strains from joining the mix. Additionally, the process would have to occur within an enclosed system to ensure its containment.

To make sure that the belt does not transfer live bacteria into the hydrocarbon collection tank, we will have a UV light aimed at the most apical point in the belt path to ensure that any bacteria picked up by the skimmer receive a lethal dose of radiation just before the hydrocarbons are removed from the bioreactor chamber.

The Prototype Design

We determined the essential concepts that needed to be developed in the prototype. As with the scaled up design, we included the belt skimmer, powered by a small motor to move the belt into and out of the system. Since our bioreactor would necessarily have live cells, our prototype operated as a completely closed system to prevent cross contamination with microbes outside the chamber.

The Belt Skimmer in Action

This video showcase our belt skimmer. The model hydrocarbons stick to the belt shown in the video and are skimmed off into a Tim Horton's coffee cup (the only disposable cup we could find in the lab.

Current Prototype with both the Sparger and Turbine

The second video shows our bioreactor prototype in action with both the sparger and turbine running.

Belt Skimmer with a Collection Chamber

This video shows the collection chamber we added to the bioreactor. There is a hole at the bottom of the chamber so that during the bioreactors' showcase the model hydrocarbons don't accumulate in the chamber.

Once we had these designs in place, we were able to start building models and presentation material. One of our goals was to have a computer animation of our design in motion. We were able to meet this goal by using the Maya and RealFlow programs. Maya is a complex and extremely versatile computer animation program used in many animated movies, including James Cameron’s “Avatar”. RealFlow is a particle-generating program, used primarily for creating fluid flow and fluid effects. Combining both of these programs, we created a seventeen second long video showing the basic idea of how our bioreactor will work. Our model will be brought to the competition for demonstration purposes.

Particle Simulation Using RealFlow2012

Open System Showing Separation of Hydrocarbon Layer

Closed System Showing Emulsified Hydrocarbons

Testing and Results

Using the physical models that we made, we were able to conduct experiments to help determine what will make our design most efficient. We received five different belt samples from a belt skimming company (Abanaki), and conducted three different tests to determine which belt is most suitable for us. Our tests sought to find the belt that picked up the most oil, least tailing pond material, and least amount of bacteria.

Additionally, we ran three different twenty-four hour bacterial growth tests in our tank to determine the effectiveness of the agitator and sparger on bacterial growth. The turbine mixes the solution so as to prevent the settling of bacterial cells and other heavier materials and to ensure even nutrient and reactant distribution in the tank. The sparger aerates the solution, which is necessary for aerobic bacteria to thrive. When assembled together, the turbine is located above the sparger thus breaking each bubble from the sparger into smaller ones. The test was conducted with a turbine and a sparger, a turbine only, and a sparger only. At the end of each experiment we measured the optical density of the solution with a spectrophotometer to quantify the bacterial growth. Operating our bioreactor with both a turbine and sparger resulted in slightly greater bacterial growth than just the turbine, which coincides with our hypothesis. In order to use the air sparger, we decided to use a HEPA filter to screen air coming out of the system to maintain constant pressure in the tank. The results are displayed below:

Furthermore, we tested our belts' ability to pick up hydrocarbons in a solution of water and commercial naphthenic acid. We dipped our belt in a solution of hexadecane, water and naphthenic acid, then removed and scraped the picked up solution into a separate beaker. This sample was then run through GC-MS to analyze the concentration of naphthenic acid found in our skimmed solution. This is an important test since we do not want to be removing too many NAs before they have the chance to be converted to hydrocarbons. Our first tests were involved using the fur material belt. The results of the GC-MS were very promising. Since we used commercial NAs, many different types of NAs were represented in our original solution. To find the concentration of each NA, the number of carbons and rings for each type of NA are counted. As can be seen below, the figures show plots of the number of carbons and rings of each NA found in the water layer and hydrocarbon layer of our skimmed solution. Based on the size of the bars on the graph, our data shows that a higher abundance of NA were found to be associated with the water and not the hydrocarbon layer. This data suggests that minimal NAs were found in our skimmed hydrocarbon layer and that most were left in the water layer.

We also conducted these tests with our preferred belt made of metallic material. The results below show the amount of each type of naphthenic acid found in the hydrocarbon layer of our skimmed solution. As can be seen, the use of this belt also resulted in the removal of very few naphthenic acids. However, the amount of naphthenic acids removed using the metallic belt was almost the same if not greater than the amount of naphthenic acid removed by the fur material belt. Based on our previous experiments (shown in Figure 3), we expected the metallic belt to pick up far fewer naphthenic acids than the fur material belt. Although this data could potentially sway our preferred belt choice, the metallic belt still picked up much fewer bacteria which is very important when analyzing the safety of our design.

The Final System

Along with physical considerations of the containment unit, we must also consider the composition and growth of the bacteria in the reactor. Each OSCAR bacterium would have the most suitable kill-switch circuit attached to its respective hydrocarbon conversion circuit. The bacterium would also have a deletion of a gene for the biosynthesis of glycine. Glycine would be supplemented in our defined production media, but cells would not survive outside of the bioreactor where glycine is absent. We envision OSCAR to be a co-culture of decarboxylation, decatecholization, denitrogenation, and desulfurization. Lastly, due to the energetically expensive nature of maintaining the circuits, we anticipate that if the circuits are constitutively produced cell growth rate may be very slow. Therefore in the final circuits we may want them to be activated by quorum sensing promoter systems. Essentially, when cells are at low density they focus energy on growth; when cells reach appropriate density for the reaction chamber, transcription of the circuit is enabled. Together we hope that the system will clean up recalcitrant petroleum waste and produce energy.

"

"