Team:Calgary/Project/OSCAR/Denitrogenation

From 2012.igem.org

| (61 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

<h2>Why Focus On Nitrogen Bioremediation?</h2> | <h2>Why Focus On Nitrogen Bioremediation?</h2> | ||

| - | <p>The removal of nitrogen heterocycles from the | + | <p>The removal of nitrogen heterocycles from the oil sands tailings ponds is important for both of the main goals of the OSCAR project. Since nitrogen containing compounds lower the quality and stability of fuel, their presence would be detrimental to the quality of the product that OSCAR could create (Katzer & Sivasubramanian, 1979). The presence of nitrogen compounds in our products also hinders our environmental goals as they have been shown to undergo radical changes, yielding highly genotoxic byproducts (Xu et al., 2006). Additionally, combustion of these compounds creates toxic gasses (NO<sub>x</sub>) which are also detrimental for the environment.</p> |

| - | + | ||

| - | </ | + | |

<h2>Our Model Compounds</h2> | <h2>Our Model Compounds</h2> | ||

| - | <p>Carbazole was chosen as the model compound to study nitrogen containing heterocycles as it accounts for about 70% of nitrogen by mass in petroleum tailings ponds, | + | <p>Carbazole was chosen as the model compound to study the denitrogenation of nitrogen containing heterocycles, as it accounts for about 70% of nitrogen by mass in petroleum tailings ponds. In addition to this, the fact that it is considered one of the more difficult compounds to degrade makes it an ideal choice for a model compound (Morales & Le Borgne, 2010). We hope that a pathway that is capable of degrading carbazole could also have the ability to degrade many other types of nitrogen containing compounds found in the tailings ponds with similar structures.</p> |

| - | </html>[[File: | + | </html>[[File:Model compounds denitrogenation calgary12.jpg|thumb|500px|centre|Figure 1: Model compounds used to test the ability of our system to remove nitrogen containing compounds.]]<html> |

| - | |||

| - | < | + | <h2>How Are We Going To Accomplish This?</h2> |

| + | <p>Through literature review, we found a <i>Pseudomonas</i> genus that is capable of converting carbazole into catechol. This conversion is carried out through an enzymatic pathway consisting of carbazole-1,9-dioxygenase (CarA) and an enzyme called anthranilate 1,2-dioxygenase. CarA is a 4 part enzyme encoded by three genes: <i>carAa, carAc</i> and <i>carAd</i>. It selectively cleaves the first C-N bond in a nitrogen containing ring structure, converting carbazole into 2'-aminobiphenyl-2,3-diol (Xu et al, 2006,Morales & Le Borgne, 2010). After this step anthranilate 1,2-dioxygenase enzyme, encoded by the <i>ant</i> operon carries out the removal of nitrogen from the structure (Diaz & Garcia, 2010). We chose to proceed with this organism in the hope that it would also be able to act on similar nitrogen heterocycle compounds. </p>. | ||

| - | <h2> | + | </html>[[File:CarA pathway Calgary12.jpg|thumb|420px|center|Figure 2: Action of the CarA enzyme complex.]]<html> |

| + | |||

| + | <h2> Does It Work? </h2> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Upon obtaining our carbazole-degrading <i>Pseudomonas</i> strain, we wanted to validate our approach. We performed an initial carbazole degradation assay where a <i>Pseudomonas</i> culture was incubated with carbazole, and monitored degradation of the compound over time. Our detailed protocol can be found <a href="https://2012.igem.org/Team:Calgary/Notebook/Protocols/carbazole">here.</a></p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </html>[[File:LD2 degradation september data calgary12.jpg|thumb|420px|right|Figure 3: Carbazole loss demonstrated after culturing with <i>Pseudomonas sp. LD2</i>, the source of the <i>car</i> and <i>ant</i> genes.]]<html> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Our data suggests that over time carbazole levels decrease, which is shown by the difference seen between day 0 and day 13. However, these results also show some limitations in the native pathway that we hope our synthetic approach will be able to overcome. Firstly, we only see modest loss of carbazole after 13 days, which would not be quick enough for OSCAR's large-scale bioreactor. Secondly, the system must be glucose free for any significant carbazole loss to occur, as no significant decrease in carbazole levels was seen when glucose was also present in the media. An absence of glucose in our bioreactor system would not be feasible. The reason for this trend may be due to the P<sup>ant</sup> promoter, the native promoter upstream of the carbazole degrading genes becoming deactivated in the presence of a preferred fuel source such as glucose. As such, we wanted to introduce an alternative promoter. This promoter may also gave the potential to upregulate transcription levels, making the degradation process more efficient.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h2> An Alternative? </h2> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p> As we want our system to act on a variety of substrates, we were also concerned about the specificity of the anthranilate 1,2-dioxygenase enzyme. It is designed to act on the substrate anthranilate which is produced in the native pathway by the actions of the carB and carC enzymes, however since our synthetic pathway does not include these genes as they do not directly attack nitrogen there is a chance that this enzyme will not interact with our remaining nitrogen groups. To this end, we also wanted to explore a deaminase enzyme (AmdA) from <i>Rhodococcus erythropolis</i> that has been shown to selectively cleave the 2nd C-N bond from a variety of nitrogen heterocycles (Kilbane et al., 2002, Kayser & Kilbane, 2005). This allows an alternative pathway for the 2nd step of nitrogen removal, possibly making the system more efficient and should show less substrate specificity than the <i>ant</i> genes allowing us to degrade a wider range of nitrogen containing rings.</p> | ||

| - | + | </html>[[File:Carbazole degradation lower pathway calgary12.png|thumb|420px|centre|Figure 4: 2 options for the final step in the pathway.]]<html> | |

| - | < | + | <h2> Testing the Amidase Enzyme </h2> |

| - | </ | + | <p> In order to independently test the function of the AmdA enzyme, we needed to inoculate cells containing this biobrick with a model compound that contained a primary amide and/or amine group. From a list of compounds that were shown to be degraded by <i>Rhodococcus</i> cells containing this gene (Hirrlinger et al., 1996) we decided on benzamide as a model compound as it also contained both the ring and carbonyl groups that that are a focus of OSCAR. As Figure 5 shows, the group of cells that were cultured with <i>E. coli</i> containing the Amidase gene were able to reduce the amount of benzamide to trace levels that were not detectable by gas chromatography, while <i>E. coli</i> cells were not able to degrade the benzamide any more than a negative control with no bacteria. Furthermore, the smaller peak with a lower retention time indicates the formation of a new compound as a result of the enzyme's actions.</p> |

| - | < | + | </html>[[File:Calgary AmdA Chromatograph.png|thumb|420px|centre|Figure 5: GC chromatograph demonstrating the degradation of benzamide by <i>AmdA</i> compared to an <i>E. coli</i> control. Additionally, a smaller peak with an earlier retention time is produced solely in the sample run.]]<html> |

| - | </ | + | <p>Figure 6 shows the identity of these two peaks. On the left we confirm that the large peak in Figure 5 that disappears after 40 hours inoculation with AmdA containing <i>E. coli</i> is benzamide. The compound on the right shows that, as expected, the NH<sub>2</sub> group has been replaced by AmdA with an OH group creating benzoic acid. The peak is smaller because benzoic acid is a central metabolite in <i>E. coli</i> that is used as a part of many natural pathways and is degraded as it is produced (Kanehisa Laboratories, 2010). In the final OSCAR system, whatever <a href="https://2012.igem.org/Team:Calgary/Project/OSCAR/Decarboxylation">carboxylic acids</a> still left over as a result of this amide conversion could be degraded by the PetroBrick into hydrocarbons.</p> |

| - | < | + | </html>[[File:Calgary AmdA MSData.png|thumb|420px|centre|Figure 6: Mass Spectra for the peak at a retention time of 10.5 minutes from Figure 7 representing the substrate benzamine. Additionally, the peak at retention time of 9 minutes represents benzoic acid based on its mass suggesting that their is a small accumulation of product.]]<html> |

| - | <p> | + | <p>These results show that we have designed a biobrick capable of performing the 2nd half of nitrogen ring degradation as well as removing existing amines and amides from toxins. Expression of the <i>AmdA</i> gene in <i>E. coli</i> is also a novel finding as previous attempts to express similar amidase proteins from <i>Rhodococcus</i> in <i>E. coli</i> have not produced viable proteins (Mayaux et al, 1991). |

| - | </ | + | <a name="nitrogen"></a><h2> Putting It All Together- Where Are We At? </h2> |

| - | <p> | + | <p>Currently the <i>carA</i> genes have all been biobricked individually (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K902032">BBa_K902032</a>,<a href="http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K902033">BBa_K902033</a> and <a href="http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K902034">BBa_K902034</a>) and the <i>carAd</i> gene was given a silent mutation to eliminate an illegal NotI site in the native sequence via <a href="https://2012.igem.org/Team:Calgary/Notebook/Protocols/mutagenesis">site directed mutagenesis</a>. We are now in the process of adding promoter and ribosome binding site (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_J13002">BBa_J13002</a>). The <i>ant</i> genes were biobricked as a whole operon with native ribosome binding sites in between each gene and have been constructed downstream of a TetR repressible promoter and ribosome binding site (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_J13002">BBa_J13002</a>). The <a href="http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K902035"><i>AmdA</i></a> gene was also biobricked and constructed downstream of a TetR repressible promoter and ribosome binding site (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_J13002">BBa_J13002</a>) creating a constitutive generator (<a href="http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K902041">BBa_K902041</a>) . We are now almost done constructing these into lager test constructs allowing us to compare the <i>ant</i> pathway versus the <i>amdA</i> gene. Final constructs are illustrated below. </p> |

| - | </html>[[File:Carbazole Super constructs calgary12.jpg|thumb| | + | </html>[[File:Carbazole degradation constructs calgary12.png|thumb|320px|left|Figure 7: Genetic circuits for nitrogen removal. 2 operons and an additional gene have been biobricked together under 1 TetR promoter each.]]<html></html>[[File:Carbazole Super constructs calgary12.jpg|thumb|320px|right|Figure 8: Three "superconstructs" to be tested for their nitrogen removal ability.]]<html> |

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

</html> | </html> | ||

}} | }} | ||

Latest revision as of 01:23, 27 October 2012

Hello! iGEM Calgary's wiki functions best with Javascript enabled, especially for mobile devices. We recommend that you enable Javascript on your device for the best wiki-viewing experience. Thanks!

Denitrogenation

Why Focus On Nitrogen Bioremediation?

The removal of nitrogen heterocycles from the oil sands tailings ponds is important for both of the main goals of the OSCAR project. Since nitrogen containing compounds lower the quality and stability of fuel, their presence would be detrimental to the quality of the product that OSCAR could create (Katzer & Sivasubramanian, 1979). The presence of nitrogen compounds in our products also hinders our environmental goals as they have been shown to undergo radical changes, yielding highly genotoxic byproducts (Xu et al., 2006). Additionally, combustion of these compounds creates toxic gasses (NOx) which are also detrimental for the environment.

Our Model Compounds

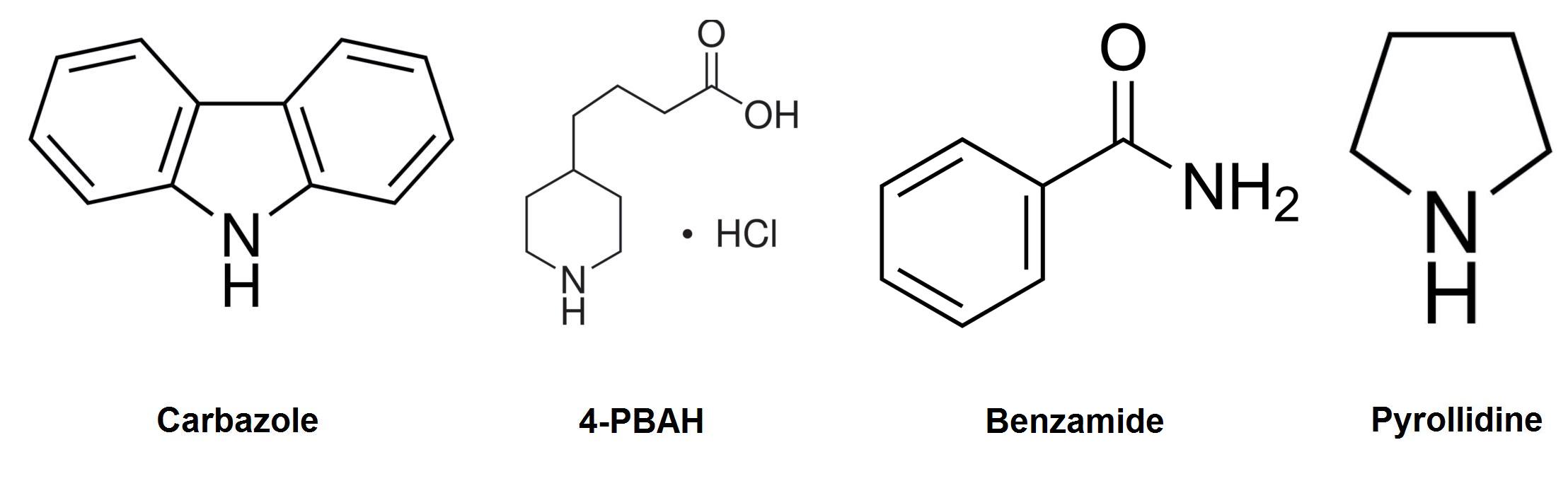

Carbazole was chosen as the model compound to study the denitrogenation of nitrogen containing heterocycles, as it accounts for about 70% of nitrogen by mass in petroleum tailings ponds. In addition to this, the fact that it is considered one of the more difficult compounds to degrade makes it an ideal choice for a model compound (Morales & Le Borgne, 2010). We hope that a pathway that is capable of degrading carbazole could also have the ability to degrade many other types of nitrogen containing compounds found in the tailings ponds with similar structures.

How Are We Going To Accomplish This?

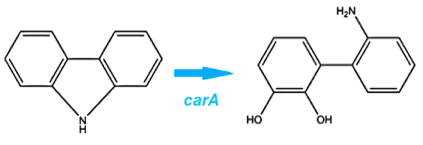

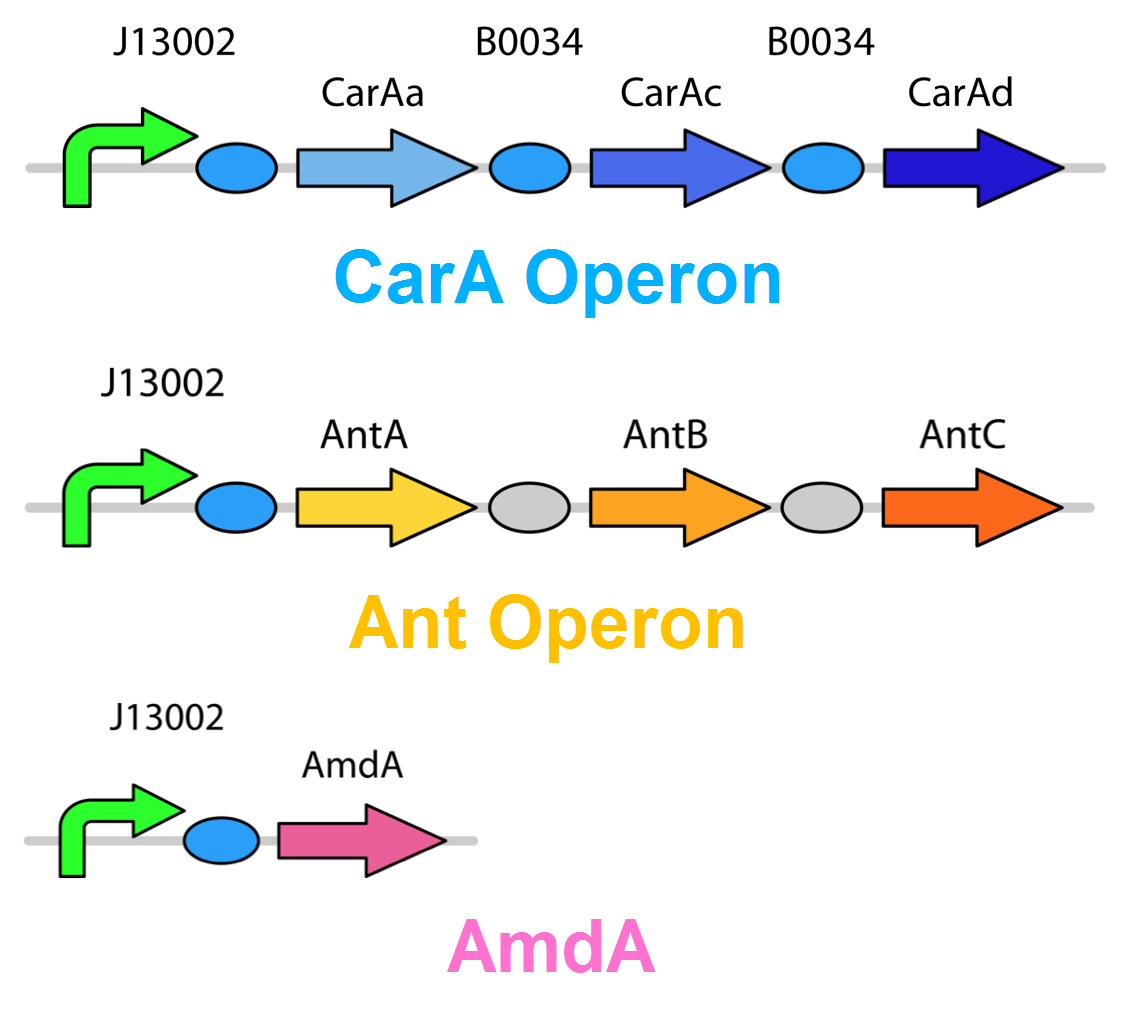

Through literature review, we found a Pseudomonas genus that is capable of converting carbazole into catechol. This conversion is carried out through an enzymatic pathway consisting of carbazole-1,9-dioxygenase (CarA) and an enzyme called anthranilate 1,2-dioxygenase. CarA is a 4 part enzyme encoded by three genes: carAa, carAc and carAd. It selectively cleaves the first C-N bond in a nitrogen containing ring structure, converting carbazole into 2'-aminobiphenyl-2,3-diol (Xu et al, 2006,Morales & Le Borgne, 2010). After this step anthranilate 1,2-dioxygenase enzyme, encoded by the ant operon carries out the removal of nitrogen from the structure (Diaz & Garcia, 2010). We chose to proceed with this organism in the hope that it would also be able to act on similar nitrogen heterocycle compounds.

.Does It Work?

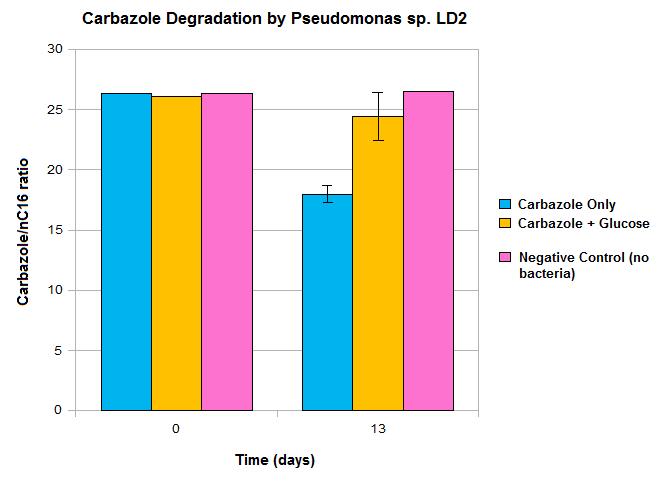

Upon obtaining our carbazole-degrading Pseudomonas strain, we wanted to validate our approach. We performed an initial carbazole degradation assay where a Pseudomonas culture was incubated with carbazole, and monitored degradation of the compound over time. Our detailed protocol can be found here.

Our data suggests that over time carbazole levels decrease, which is shown by the difference seen between day 0 and day 13. However, these results also show some limitations in the native pathway that we hope our synthetic approach will be able to overcome. Firstly, we only see modest loss of carbazole after 13 days, which would not be quick enough for OSCAR's large-scale bioreactor. Secondly, the system must be glucose free for any significant carbazole loss to occur, as no significant decrease in carbazole levels was seen when glucose was also present in the media. An absence of glucose in our bioreactor system would not be feasible. The reason for this trend may be due to the Pant promoter, the native promoter upstream of the carbazole degrading genes becoming deactivated in the presence of a preferred fuel source such as glucose. As such, we wanted to introduce an alternative promoter. This promoter may also gave the potential to upregulate transcription levels, making the degradation process more efficient.

An Alternative?

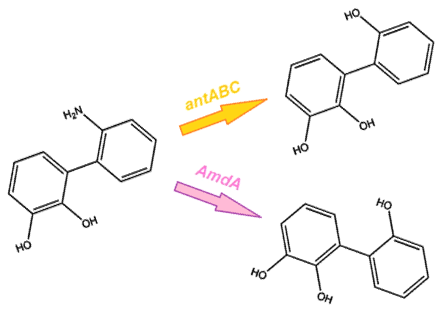

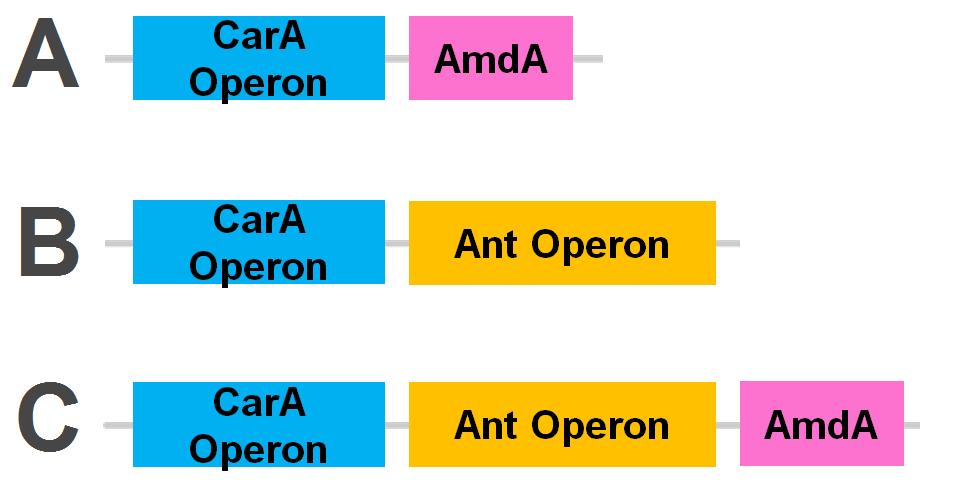

As we want our system to act on a variety of substrates, we were also concerned about the specificity of the anthranilate 1,2-dioxygenase enzyme. It is designed to act on the substrate anthranilate which is produced in the native pathway by the actions of the carB and carC enzymes, however since our synthetic pathway does not include these genes as they do not directly attack nitrogen there is a chance that this enzyme will not interact with our remaining nitrogen groups. To this end, we also wanted to explore a deaminase enzyme (AmdA) from Rhodococcus erythropolis that has been shown to selectively cleave the 2nd C-N bond from a variety of nitrogen heterocycles (Kilbane et al., 2002, Kayser & Kilbane, 2005). This allows an alternative pathway for the 2nd step of nitrogen removal, possibly making the system more efficient and should show less substrate specificity than the ant genes allowing us to degrade a wider range of nitrogen containing rings.

Testing the Amidase Enzyme

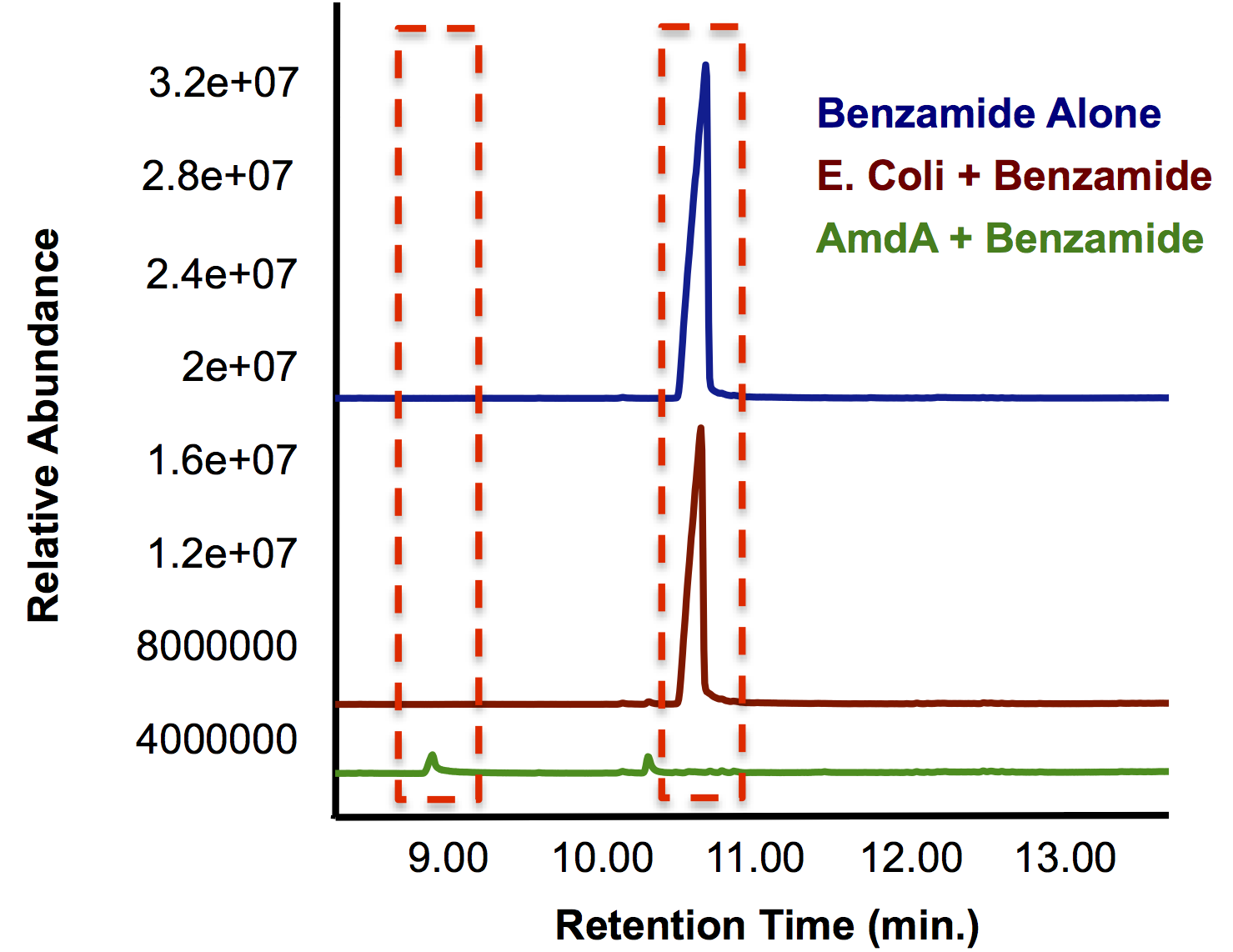

In order to independently test the function of the AmdA enzyme, we needed to inoculate cells containing this biobrick with a model compound that contained a primary amide and/or amine group. From a list of compounds that were shown to be degraded by Rhodococcus cells containing this gene (Hirrlinger et al., 1996) we decided on benzamide as a model compound as it also contained both the ring and carbonyl groups that that are a focus of OSCAR. As Figure 5 shows, the group of cells that were cultured with E. coli containing the Amidase gene were able to reduce the amount of benzamide to trace levels that were not detectable by gas chromatography, while E. coli cells were not able to degrade the benzamide any more than a negative control with no bacteria. Furthermore, the smaller peak with a lower retention time indicates the formation of a new compound as a result of the enzyme's actions.

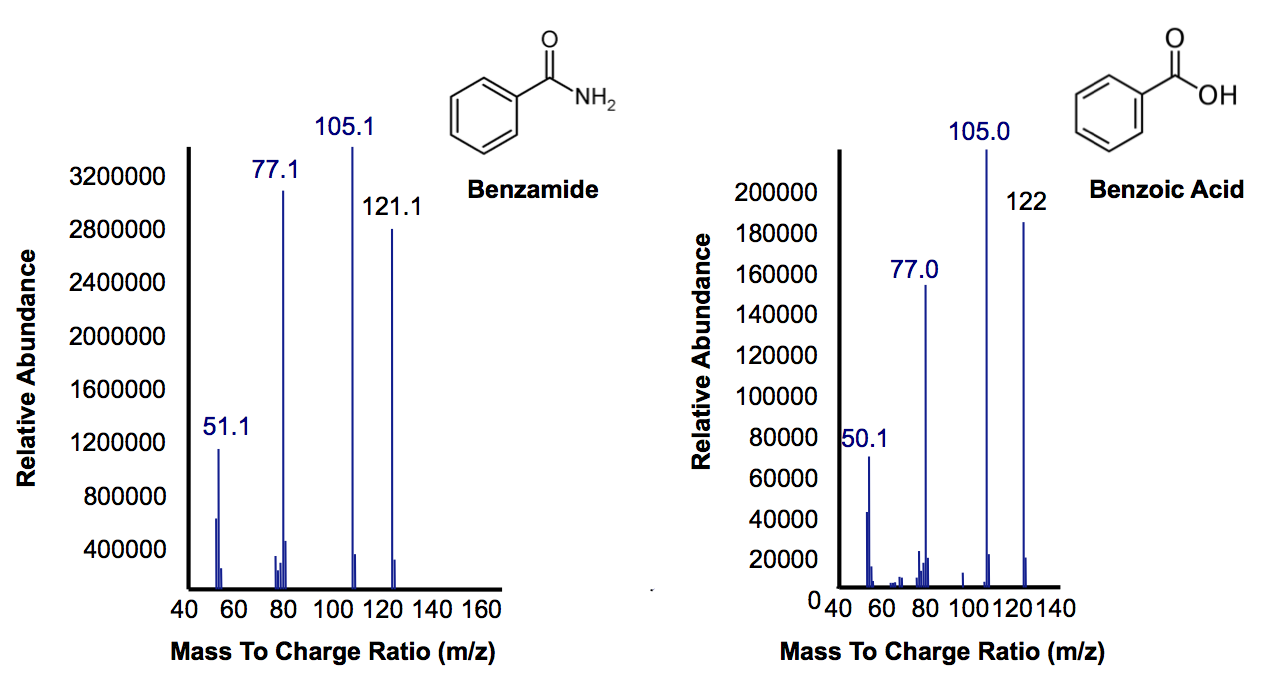

Figure 6 shows the identity of these two peaks. On the left we confirm that the large peak in Figure 5 that disappears after 40 hours inoculation with AmdA containing E. coli is benzamide. The compound on the right shows that, as expected, the NH2 group has been replaced by AmdA with an OH group creating benzoic acid. The peak is smaller because benzoic acid is a central metabolite in E. coli that is used as a part of many natural pathways and is degraded as it is produced (Kanehisa Laboratories, 2010). In the final OSCAR system, whatever carboxylic acids still left over as a result of this amide conversion could be degraded by the PetroBrick into hydrocarbons.

These results show that we have designed a biobrick capable of performing the 2nd half of nitrogen ring degradation as well as removing existing amines and amides from toxins. Expression of the AmdA gene in E. coli is also a novel finding as previous attempts to express similar amidase proteins from Rhodococcus in E. coli have not produced viable proteins (Mayaux et al, 1991).

Putting It All Together- Where Are We At?

Currently the carA genes have all been biobricked individually (BBa_K902032,BBa_K902033 and BBa_K902034) and the carAd gene was given a silent mutation to eliminate an illegal NotI site in the native sequence via site directed mutagenesis. We are now in the process of adding promoter and ribosome binding site (BBa_J13002). The ant genes were biobricked as a whole operon with native ribosome binding sites in between each gene and have been constructed downstream of a TetR repressible promoter and ribosome binding site (BBa_J13002). The AmdA gene was also biobricked and constructed downstream of a TetR repressible promoter and ribosome binding site (BBa_J13002) creating a constitutive generator (BBa_K902041) . We are now almost done constructing these into lager test constructs allowing us to compare the ant pathway versus the amdA gene. Final constructs are illustrated below.

"

"