Team:Peking/Project/Communication/Design

From 2012.igem.org

m |

|||

| (3 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

The first concern was what kind of light emitting cell we should choose. It has to meet several requirements: | The first concern was what kind of light emitting cell we should choose. It has to meet several requirements: | ||

<ul><li> | <ul><li> | ||

| - | 1) The emission spectrum of the light should have a maximum intensity at approximately 480nm, which is the maximum absorption wavelength of | + | 1) The emission spectrum of the light should have a maximum intensity at approximately 480nm, which is the maximum absorption wavelength of the <i>Luminesensor</i>. |

</li><li> | </li><li> | ||

2) The cell must require no excitation to emit light. | 2) The cell must require no excitation to emit light. | ||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

3) The cell must be able to emit light at 30<sup>o</sup>C, which is the functional temperature of our light sensitive repressor. | 3) The cell must be able to emit light at 30<sup>o</sup>C, which is the functional temperature of our light sensitive repressor. | ||

</li><li> | </li><li> | ||

| - | 4) The light needs to be strong enough to be detected by | + | 4) The light needs to be strong enough to be detected by <i>Luminesensor</i>. |

</li></ul></p><p> | </li></ul></p><p> | ||

After browsing through scientific literature, we chose the bacterial luciferase (lux system), which originated from <i>Vibrio fischeri</i>. It is expected to emit blue-green light with a maximum intensity at 490nm. The light emitting reaction only requires bacteria metabolic substrates like FMNH<sub>2</sub>, O<sub>2</sub> and fatty aldehyde, which means we would not have to add exogenous substrates into the system. Also, it was reported that the best temperature for <i>E. coli</i> transformed with lux genes to emit light is 30<sup>o</sup>C. | After browsing through scientific literature, we chose the bacterial luciferase (lux system), which originated from <i>Vibrio fischeri</i>. It is expected to emit blue-green light with a maximum intensity at 490nm. The light emitting reaction only requires bacteria metabolic substrates like FMNH<sub>2</sub>, O<sub>2</sub> and fatty aldehyde, which means we would not have to add exogenous substrates into the system. Also, it was reported that the best temperature for <i>E. coli</i> transformed with lux genes to emit light is 30<sup>o</sup>C. | ||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

<p class="description" style="text-align:center;width:350px;">Figure 2. Set-up for Light Communication</p> | <p class="description" style="text-align:center;width:350px;">Figure 2. Set-up for Light Communication</p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="PKU_context floatR"> | <div class="PKU_context floatR"> | ||

Latest revision as of 05:11, 26 October 2012

Light Emitting Cell

The first concern was what kind of light emitting cell we should choose. It has to meet several requirements:

- 1) The emission spectrum of the light should have a maximum intensity at approximately 480nm, which is the maximum absorption wavelength of the Luminesensor.

- 2) The cell must require no excitation to emit light.

- 3) The cell must be able to emit light at 30oC, which is the functional temperature of our light sensitive repressor.

- 4) The light needs to be strong enough to be detected by Luminesensor.

After browsing through scientific literature, we chose the bacterial luciferase (lux system), which originated from Vibrio fischeri. It is expected to emit blue-green light with a maximum intensity at 490nm. The light emitting reaction only requires bacteria metabolic substrates like FMNH2, O2 and fatty aldehyde, which means we would not have to add exogenous substrates into the system. Also, it was reported that the best temperature for E. coli transformed with lux genes to emit light is 30oC.

Fortunately, we found an already existing biobrick in the Parts Registry constructed by Cambridge 2010 iGEM team – luxbrick (BBa_K325909). They have successfully optimized the codon for expression and transformed the lux system into E. coli. In this biobirck, the light emitting related genes are placed under the pBAD promoter, and the cells are able to produce relatively strong blue-green light under the induction of L-arabinose. Therefore, we decided to use this part to construct light emitting cell for bio-luminescence communication.

Figure 1. TOP10 cells transformed with luxbrick which is a biobrick constructed by Cambridge 2010 iGEM team

Set-up

The next issue we placed our focus on is how to build a device to enable cells to talk through light in an easily observable way. To obtain this goal, we first had to solve some problems:

- 1) As the intensity of bacteria luminescence may not be high enough, we had to place light emitting cells and the sensing cells in close proximity. However, it has better not mix the cells together due to the need to observe the reaction of the sensor cells separately.

- 2) The light emitting reaction highly depended on the availability of O2 in the environment. Therefore, our means of maintaining the concentration of O2 was an important issue.

- 3) As our light sensing cell is very sensitive, which has been shown in the characterization of our Luminesensor, it’s important to exclude the influence of other sources light.

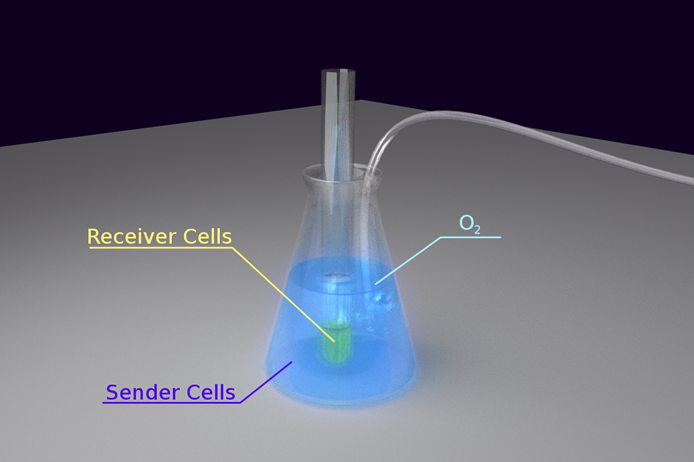

To solve the problem of O2 maintenance, we decided to put the light emitting cell in a conical flask and keep fresh air pumping into the culture. We put a test tube containing light sensing cell in the conical flask, immersing the sensor cell culture into the light emitting cell to keep them in close proximity. To exclude the influence of the other sources of light in the environment, the whole set-up was wrapped tightly with aluminum foil. Finally, the whole set-up was kept on a shaking incubator at 30oC.

The set-up is shown in the figure below:

Figure 2. Set-up for Light Communication

Reference

- 1. Slock, J.(1995) Transformation Experiments Using Bioluminescence Genes of Vibrio fischeri. Am.Biology.Teacher, 57:225:227

- 2. Meighen, E.A.(1994) Genetics of bacterial bioluminescence. Annu.Rev.Genet., 28:117:139

"

"