Team:Michigan/Results

From 2012.igem.org

(Difference between revisions)

| (31 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

Introduction | Introduction | ||

</h3> | </h3> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

In order to test the effectiveness of the recombinases used in our system, we developed two assays -- an “asymmetrical digest” reporter and a fluorescence reporter. The former is used to directly test the inversion of the target DNA region, while the latter is used to demonstrate inversion induced protein expression. | In order to test the effectiveness of the recombinases used in our system, we developed two assays -- an “asymmetrical digest” reporter and a fluorescence reporter. The former is used to directly test the inversion of the target DNA region, while the latter is used to demonstrate inversion induced protein expression. | ||

| Line 18: | Line 19: | ||

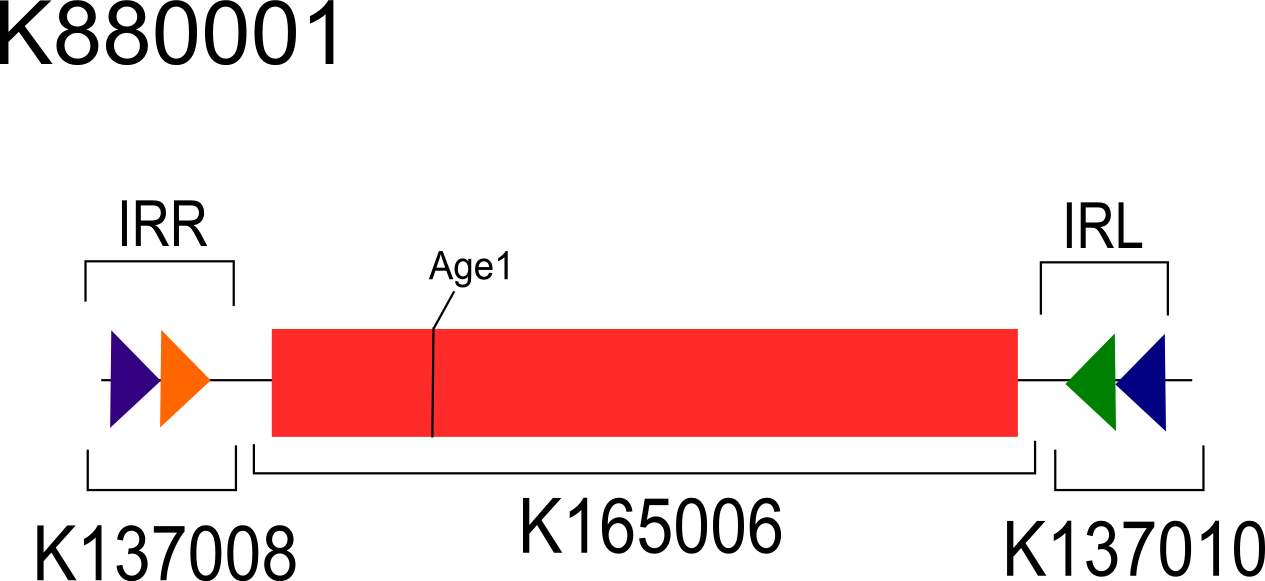

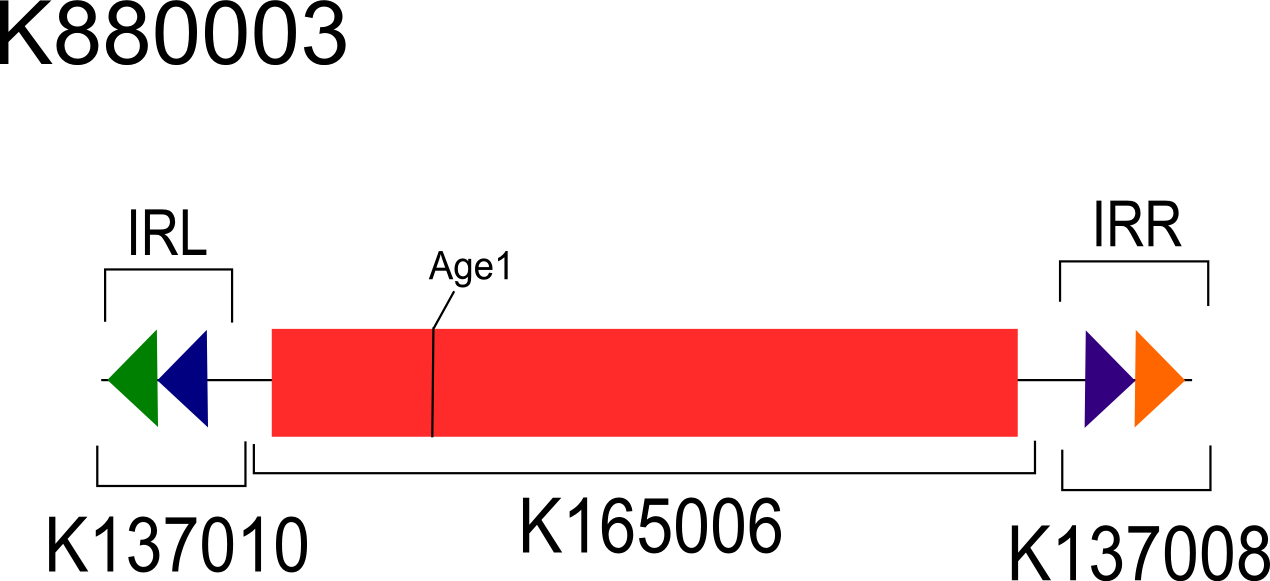

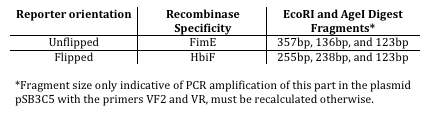

The two asymmetrical digest reporters in their unflipped state (invertible by FimE) are shown in figures 2 and 3. These reporters rely on an off-center AgeI restriction site which will yield fragments of varying size depending on the orientation of the inversion region. Table 1 shows the expected sizes of the fragments in each orientation. The differences between the reporters are discussed below. | The two asymmetrical digest reporters in their unflipped state (invertible by FimE) are shown in figures 2 and 3. These reporters rely on an off-center AgeI restriction site which will yield fragments of varying size depending on the orientation of the inversion region. Table 1 shows the expected sizes of the fragments in each orientation. The differences between the reporters are discussed below. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | [[File:MichDiagram1.png|350px|thumb|left| Figure 1. A diagram of the asymmetrical reporter K880001]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:MichDiagram2.png|350px|thumb|left| Figure 2. A diagram of the asymmetrical reporter K880003]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:MichTable1.png|300px|thumb|center| Table 1. Expected outcomes for the asymmetrical digest assay of the reporters K880001 and K880003. ]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

<h2> | <h2> | ||

| Line 24: | Line 38: | ||

The fluorescent reporters, show in in figures 3 and 4, have a constitutive tetR promoter within the inversion site, allowing for the expression of GFP in the flipped orientation. | The fluorescent reporters, show in in figures 3 and 4, have a constitutive tetR promoter within the inversion site, allowing for the expression of GFP in the flipped orientation. | ||

| - | <br> | + | <br> |

| - | + | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | + | [[File:MichFig3.png|350px|thumb|center| Fig 3. A diagram of the fluorescent reporter K137058]] | |

| - | + | [[File:MichFig4.png|350px|thumb|center | Fig 4. A diagram of the fluorescent reporter K137058]] | |

| - | |||

| - | |||

<html> | <html> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

<h3> | <h3> | ||

| Line 44: | Line 54: | ||

Negative Fluorescent Reporter (BBa_K137058) Data | Negative Fluorescent Reporter (BBa_K137058) Data | ||

</h2> | </h2> | ||

| + | |||

| + | To initially test the FimE recombinase, we utilized a reporter created by the CalTech ‘08 iGEM team (BBa_K137058) for the same purpose. The K137058 reporter in the vector pSB3C5 was co-transformed in 10-beta <i>E. coli</i> (NEB) with strong, constitutively expressed FimE (K880005-K137007) in the vector pSB1A2. Despite several co-transformation trials, no fluorescence was observed in contrast to CalTech ‘08’s results. | ||

| + | <br><br> | ||

<h2> | <h2> | ||

Negative Asymmetrically Digestible Reporter (BBa_K880003) Data | Negative Asymmetrically Digestible Reporter (BBa_K880003) Data | ||

</h2> | </h2> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | An asymmetrical digest reporter (K880003) in the vector pSB3C5 based on the inversion region found in K137058 was co-transformed in 10-beta <i>E. coli</i> (NEB) with strong, constitutively expressed FimE (K880005-K137007) in the vector pSB1A2. Colonies as well as broth subcultures of co-transformants were analyzed for inversion using the asymmetrical digest assay</html>[https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2012/a/aa/MichAsm.pdf]<html>. The asymmetrical digest reporter and <i>fimE</i> are present within the co-transformants; however, the asymmetrical digest reporter remains in the uninverted state (Fig 5, lane 3). | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:MichFig5.png|300px|thumb|none| Fig 5. A representative electrophoresis gel of the asymmetric digest assay of K880003 co-transformed with FimE. Lane 1 is a 100bp Ladder (NEB), lane 2 is K880003 transformed alone, lane 3 is K88003 co-transformed with FimE, and lane 4 is FimE transformed alone. Uninverted K880003 yields a 357bp band as seen in lane 2 and 3, while inversion induced by FimE is expected to result in a 255 and 238bp band. ]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

<h2> | <h2> | ||

Observation of IRR and IRL Orientation: | Observation of IRR and IRL Orientation: | ||

</h2> | </h2> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Scrutiny of the DNA sequence provided a possible explanation of the negative results. | ||

| + | As constructed, verified by sequencing, the orientations of IRL(K137010) and IRR (K137008) within the inversion region of K137058 were orientated 180º when compared to the natural <i>fimS</i> region (Gally et al., 1996) and a previously engineered recombinase systems (Ham et al., 2006). This resulted in the IRL and IRR being oriented such that the external half-sites are localized adjacent to the inversion region, while the internal half-sites are located externally (Fig 6). We hypothesize that this 180º orientation of the IRL and IRR is the determinative factor to the inversion negative results. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:MichFig6.png|300px|thumb|none| Fig 6. Comparison of the natural <i>fimS</i> IRR and IRL orientation to that of K137058. The orientation of IRL (Blue-Yellow-Orange) and IRR (Purple-Yellow-Green) are both exhibiting 180º orientations in K137058 (B) when compared to the natural <i>fimS</i> region (A). | ||

| + | ]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <html> | ||

<h2> | <h2> | ||

Modified Asymmetrically Digestible Reporter (BBa_K880001) Data: | Modified Asymmetrically Digestible Reporter (BBa_K880001) Data: | ||

</h2> | </h2> | ||

| + | |||

| + | To test the hypothesis that the IRL and IRR orientations were the determinative factor to the inversion negative results observed, we created a second asymmetrical reporter (K880001). K880001 was engineered such that the IRL is situated on the right of the inverted region and the IRR is situated on the left. This IRL/IRR orientation restores the orientation as found in the natural <i>fimS</i> region (Gally et al., 1996) and a previously engineered recombinase systems (Ham et al., 2006 ). | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The new asymmetrical digest reporter (K880001) in the vector pSB3C5 was co-transformed in 10-beta <i>E. coli</i> (NEB) with strong, constitutively expressed FimE (K880005-K137007) in the vector pSB1A2. Co-transformants colonies were analyzed for inversion using the asymmetrical digest assay</html>[https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2012/a/aa/MichAsm.pdf]<html>. The asymmetrical digest reporter and <i>fimE</i> (700bp band Fig7, Lanes 2-4) are both present within the co-transformants. The asymmetrical digest reporter was observed in a partially flipped state exhibiting both the 353bp band as well as the 255/238bp bands (Fig 7, Lane 2-4). It has been noted that fim inversions induced by FimE in a previously engineered recombinase systems exhibited low efficiency resulting in a mixed population of flipped and unflipped inversion regions (Ham et al., 2008). | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | To further characterize the new asymmetrical digest reporter (K880001) in the vector pSB3C5 was transformed into <i>E. coli</i> DH5α</i>, a strain with endogenous FimE. In accordance with the co-transformation experiment, the asymmetrical digest reporter was observed in a partially flipped state (Fig 8, Lane 2). | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:MichFig7.png|300px|thumb|left|10-beta <i>E. coli</i> with FimE. Lane 1 is a 100bp Ladder (NEB), lane 2-4 are K880001 co-transformed with FimE showing a mixed state indicated the presence the uninverted K880001 yields a 357bp band, while inversion induced by FimE is expected to result in a 255/238bp band. ]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:MichFig8.jpg|300px|thumb|none|Fig 8. An electrophoresis gel of the asymmetric digest assay of K880001 in <i>E. coli</i> DH5𝛼 with endogenous FimE. Lane 1 is a 100bp Ladder (NEB), lane 2 is K880001 showing a mixed state indicated by the presence the uninverted K880001 yielding the 357bp band, and the inverted K880001 resulting in a 255 and 238bp band. ]] | ||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | |||

<h2> | <h2> | ||

Negative Modified Fluorescent Reporter (BBa_K880002) Data: | Negative Modified Fluorescent Reporter (BBa_K880002) Data: | ||

</h2> | </h2> | ||

| + | |||

| + | To additionally test our hypothesis we made a fluorescent reporter with the IRR and IRL orientation, analogous to K880001. Unexpectedly, we did not observe fluorescence possibly attributable to partially flipped states observed in the K880001 co-transformation assays (Fig 7 and 8 above) | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br><br> | ||

<h2> | <h2> | ||

| - | Observation of HbiF induced fimbriation in | + | Observation of HbiF induced fimbriation in DH5α |

</h2> | </h2> | ||

| + | |||

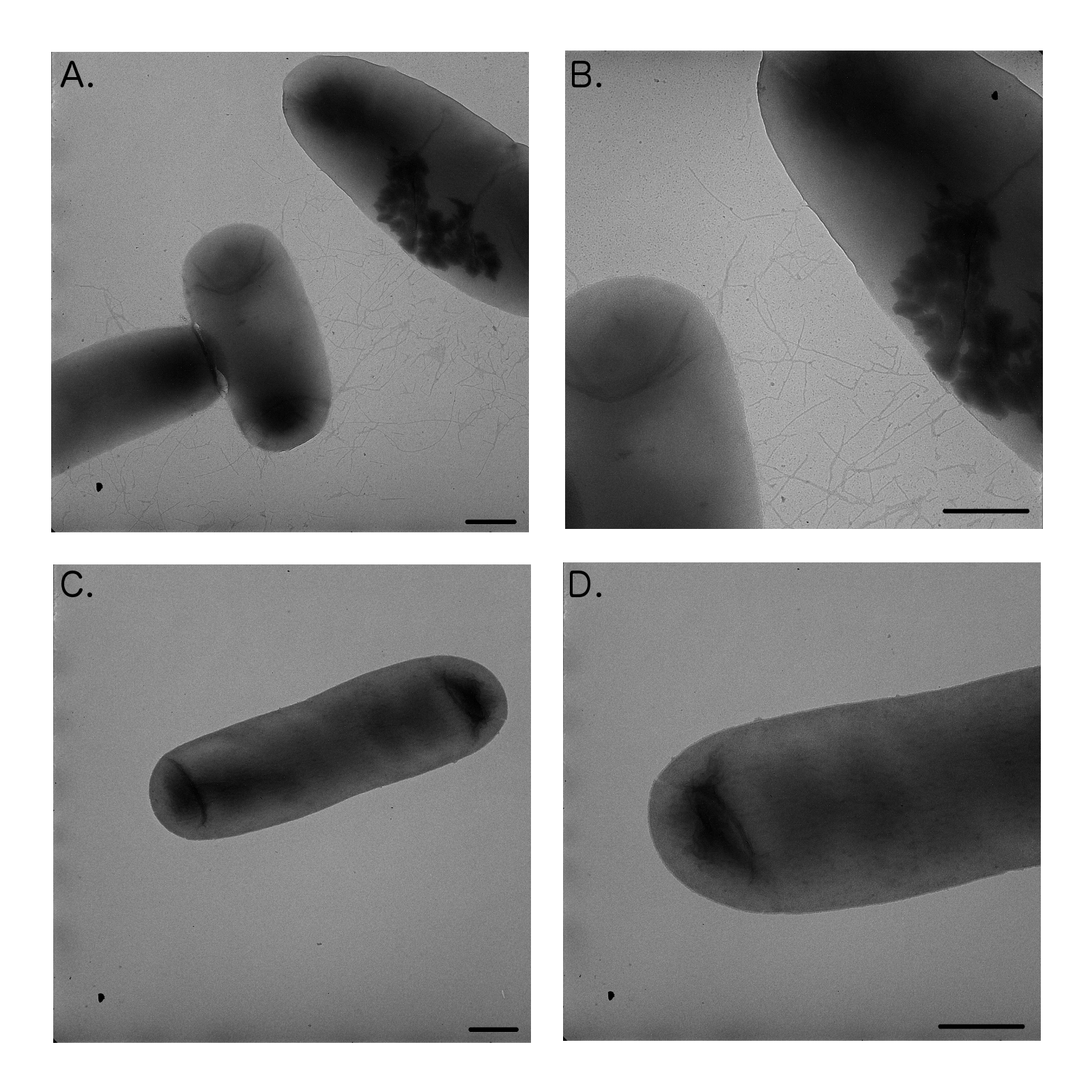

| + | We were hoping to test HbiF on the FimE-flipped reporters however due to only obtaining partially flipped states we were unable to isolate a flipped plasmid to test this. Upon transformation of <i>E. coli</i> DH5α with strong, constitutively expressed HbiF (K880005-K880000), we noticed cell aggregates in liquid cultures that were difficult to resuspend upon pelleting. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of the culture showed that HbiF expressing cells were fimbriated (Fig 9, A and B), suggesting that HbiF is expressed and actively working on the natural <i>fimS</i> region flipping from “OFF” to “ON” (Xie et al., 2006). | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:MichFig9.png|300px|thumb|none|TEM micrographs of <i>E. coli</i> DH5𝛼 cells transformed with HbiF in pSB1A2 (A, B) versus untransformed <i>E. coli</i> DH5𝛼 cells (C, D). Fimbriae are clearly visible in the cells expressing HbiF (A, B), while absent in the control cells (C, D). Bar length indicates 500 nm.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>Conclusion</h3> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | We have designed a protein expression system utilizing unidirectional recombinases HbiF and FimE, and have tested for the activities of both recombinases by creating two asymmetric digest assays. The effect of recombinase activity on the reporter was observed more consistently than what was shown by the FimE reporter (K137058) as submitted by Caltech 2008, which we did not observe to have an inversion. We created two asymmetrical digest reporters in order to obtain semi-quantitative data on recombinase activity at the DNA level. Using the digestible reporters, we determined that FimE has a low inversion activity. We demonstrated that <i>hbiF</i> as submitted to the Registry is functional. DH5α transformed with <i>hbiF</i> has a fimbriated phenotype, suggesting HbiF activity on the native <i>fimS</i>. | ||

| + | <br><br> | ||

| + | Native recombinase activity in <i>E. coli</i> is augmented by DNA-bending proteins. As inversion is accomplished through a Holliday junction intermediate, the invertible regions must at some point be in close proximity with each other. The simplicity of our system likely contributes to the lower efficiency of the recombinases. Co-expression of the recombinase system with DNA-bending proteins, such as leucine-responsive regulatory proteins and integration host factor protein, will increase the probability that the invertible regions are at a distance preferred for higher recombinase activity. | ||

| + | <br><br> | ||

| + | Production and degradation rates of each recombinase within the system can be further optimized by investigating combinations of promoters and RBSs, and the use of degradation tags. Imprecise regulation of recombinase expression can also be compensated by preventing the leaky gene expression from forming proteins, or counteracting the effects of leaky protein expression. Although the system is more complicated than what we envisioned, it continues to be a viable and interesting way of manipulating genetic information, and have the potential to become increasingly complex and robust with additional components. | ||

| + | <br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h2>References</h2> | ||

| + | Ham et al., Biotechnol. Bioeng. (2006), Vol. 94(1) | ||

| + | <br><br> | ||

| + | Ham et al., PLoS ONE (2008), 3(7) | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br><br> | ||

| + | Gally et al., Molecular Microbiology (1996) 21(4) | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br><br> | ||

| + | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

Latest revision as of 21:30, 14 October 2012

Introduction

In order to test the effectiveness of the recombinases used in our system, we developed two assays -- an “asymmetrical digest” reporter and a fluorescence reporter. The former is used to directly test the inversion of the target DNA region, while the latter is used to demonstrate inversion induced protein expression.

The Asymmetrical Digest Reporters

The two asymmetrical digest reporters in their unflipped state (invertible by FimE) are shown in figures 2 and 3. These reporters rely on an off-center AgeI restriction site which will yield fragments of varying size depending on the orientation of the inversion region. Table 1 shows the expected sizes of the fragments in each orientation. The differences between the reporters are discussed below.

The Fluorescent Reporters

The fluorescent reporters, show in in figures 3 and 4, have a constitutive tetR promoter within the inversion site, allowing for the expression of GFP in the flipped orientation.

Results

Negative Fluorescent Reporter (BBa_K137058) Data

To initially test the FimE recombinase, we utilized a reporter created by the CalTech ‘08 iGEM team (BBa_K137058) for the same purpose. The K137058 reporter in the vector pSB3C5 was co-transformed in 10-beta E. coli (NEB) with strong, constitutively expressed FimE (K880005-K137007) in the vector pSB1A2. Despite several co-transformation trials, no fluorescence was observed in contrast to CalTech ‘08’s results.Negative Asymmetrically Digestible Reporter (BBa_K880003) Data

An asymmetrical digest reporter (K880003) in the vector pSB3C5 based on the inversion region found in K137058 was co-transformed in 10-beta E. coli (NEB) with strong, constitutively expressed FimE (K880005-K137007) in the vector pSB1A2. Colonies as well as broth subcultures of co-transformants were analyzed for inversion using the asymmetrical digest assay[1]. The asymmetrical digest reporter and fimE are present within the co-transformants; however, the asymmetrical digest reporter remains in the uninverted state (Fig 5, lane 3).

Fig 5. A representative electrophoresis gel of the asymmetric digest assay of K880003 co-transformed with FimE. Lane 1 is a 100bp Ladder (NEB), lane 2 is K880003 transformed alone, lane 3 is K88003 co-transformed with FimE, and lane 4 is FimE transformed alone. Uninverted K880003 yields a 357bp band as seen in lane 2 and 3, while inversion induced by FimE is expected to result in a 255 and 238bp band.

Observation of IRR and IRL Orientation:

Scrutiny of the DNA sequence provided a possible explanation of the negative results. As constructed, verified by sequencing, the orientations of IRL(K137010) and IRR (K137008) within the inversion region of K137058 were orientated 180º when compared to the natural fimS region (Gally et al., 1996) and a previously engineered recombinase systems (Ham et al., 2006). This resulted in the IRL and IRR being oriented such that the external half-sites are localized adjacent to the inversion region, while the internal half-sites are located externally (Fig 6). We hypothesize that this 180º orientation of the IRL and IRR is the determinative factor to the inversion negative results.

Modified Asymmetrically Digestible Reporter (BBa_K880001) Data:

To test the hypothesis that the IRL and IRR orientations were the determinative factor to the inversion negative results observed, we created a second asymmetrical reporter (K880001). K880001 was engineered such that the IRL is situated on the right of the inverted region and the IRR is situated on the left. This IRL/IRR orientation restores the orientation as found in the natural fimS region (Gally et al., 1996) and a previously engineered recombinase systems (Ham et al., 2006 ).The new asymmetrical digest reporter (K880001) in the vector pSB3C5 was co-transformed in 10-beta E. coli (NEB) with strong, constitutively expressed FimE (K880005-K137007) in the vector pSB1A2. Co-transformants colonies were analyzed for inversion using the asymmetrical digest assay[2]. The asymmetrical digest reporter and fimE (700bp band Fig7, Lanes 2-4) are both present within the co-transformants. The asymmetrical digest reporter was observed in a partially flipped state exhibiting both the 353bp band as well as the 255/238bp bands (Fig 7, Lane 2-4). It has been noted that fim inversions induced by FimE in a previously engineered recombinase systems exhibited low efficiency resulting in a mixed population of flipped and unflipped inversion regions (Ham et al., 2008).

To further characterize the new asymmetrical digest reporter (K880001) in the vector pSB3C5 was transformed into E. coli DH5α, a strain with endogenous FimE. In accordance with the co-transformation experiment, the asymmetrical digest reporter was observed in a partially flipped state (Fig 8, Lane 2).

Fig 8. An electrophoresis gel of the asymmetric digest assay of K880001 in E. coli DH5𝛼 with endogenous FimE. Lane 1 is a 100bp Ladder (NEB), lane 2 is K880001 showing a mixed state indicated by the presence the uninverted K880001 yielding the 357bp band, and the inverted K880001 resulting in a 255 and 238bp band.

Negative Modified Fluorescent Reporter (BBa_K880002) Data:

To additionally test our hypothesis we made a fluorescent reporter with the IRR and IRL orientation, analogous to K880001. Unexpectedly, we did not observe fluorescence possibly attributable to partially flipped states observed in the K880001 co-transformation assays (Fig 7 and 8 above)Observation of HbiF induced fimbriation in DH5α

We were hoping to test HbiF on the FimE-flipped reporters however due to only obtaining partially flipped states we were unable to isolate a flipped plasmid to test this. Upon transformation of E. coli DH5α with strong, constitutively expressed HbiF (K880005-K880000), we noticed cell aggregates in liquid cultures that were difficult to resuspend upon pelleting. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of the culture showed that HbiF expressing cells were fimbriated (Fig 9, A and B), suggesting that HbiF is expressed and actively working on the natural fimS region flipping from “OFF” to “ON” (Xie et al., 2006).

Conclusion

We have designed a protein expression system utilizing unidirectional recombinases HbiF and FimE, and have tested for the activities of both recombinases by creating two asymmetric digest assays. The effect of recombinase activity on the reporter was observed more consistently than what was shown by the FimE reporter (K137058) as submitted by Caltech 2008, which we did not observe to have an inversion. We created two asymmetrical digest reporters in order to obtain semi-quantitative data on recombinase activity at the DNA level. Using the digestible reporters, we determined that FimE has a low inversion activity. We demonstrated that hbiF as submitted to the Registry is functional. DH5α transformed with hbiF has a fimbriated phenotype, suggesting HbiF activity on the native fimS.

Native recombinase activity in E. coli is augmented by DNA-bending proteins. As inversion is accomplished through a Holliday junction intermediate, the invertible regions must at some point be in close proximity with each other. The simplicity of our system likely contributes to the lower efficiency of the recombinases. Co-expression of the recombinase system with DNA-bending proteins, such as leucine-responsive regulatory proteins and integration host factor protein, will increase the probability that the invertible regions are at a distance preferred for higher recombinase activity.

Production and degradation rates of each recombinase within the system can be further optimized by investigating combinations of promoters and RBSs, and the use of degradation tags. Imprecise regulation of recombinase expression can also be compensated by preventing the leaky gene expression from forming proteins, or counteracting the effects of leaky protein expression. Although the system is more complicated than what we envisioned, it continues to be a viable and interesting way of manipulating genetic information, and have the potential to become increasingly complex and robust with additional components.

References

Ham et al., Biotechnol. Bioeng. (2006), Vol. 94(1)Ham et al., PLoS ONE (2008), 3(7)

Gally et al., Molecular Microbiology (1996) 21(4)

"

"