Team:Washington/Optogenetics

From 2012.igem.org

m |

|||

| (10 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

---- | ---- | ||

<h1 id='Methods'>Methods<html><a href="#Background"><font size="3">[Top]</font></a></html></h1> | <h1 id='Methods'>Methods<html><a href="#Background"><font size="3">[Top]</font></a></html></h1> | ||

| - | [[File:Picture1 wtf alex.png|thumb|right|400px| | + | [[File:Picture1 wtf alex.png|thumb|right|400px|The basic operation of our light system.]] |

===Characterization of a light inducible protein expression system for the tuning of biological pathways=== | ===Characterization of a light inducible protein expression system for the tuning of biological pathways=== | ||

| - | Chromatic tuning is based | + | Chromatic tuning is based on light-induced protein interactions. The most basic of these systems is a monochromatic system, in which a specific wavelength of light changes a protein's conformation temporarily, causing it to interact differently with its environment. Our system involves the use of a photoreceptor CcaS attached to a chromophore and CcaR, a response regulator. The chromophore, when illuminated with green light (λ=535nm) will undergo a conformational change leading to autophosphorylation of the photoreceptor CcaS. Increased autophosphorylation leads to activation of the response regulator via phosphorylation. The activated response regulator will then bind to the promoter P<sub>cpcG2</sub>, activating transcription and producing beta-galactosidase. Beta-galactosidase will cleave the S-gal, creating a black precipitate and allowing us to know visually that our light sensor is working. Red light (λ=672nm), on the other hand, changes the protein conformation such that it resists phosphorylation, thus not binding to the promoter and not allowing gene expression. Any gene placed after the promoter can be theoretically controlled by the exposure of λ=535nm and λ=637nm light to the system. |

| - | [[File:Picture 2.png|thumb|left|400px| | + | [[File:Picture 2.png|thumb|left|400px|By inserting the light system into ''E. coli'', we can test its functionality by measuring pigment density.]] |

A blue light sensor (Lov_Tap BBa_K191003) was found in the registry and transformed to be used as one of our main components to create a functioning blue light sensor, activated at 470 nm wavelengths of light. The part taken from the registry was joined with a TetR inverter, since originally the blue light sensor repressed gene expression. The newly added TetR inverter then suppressed the regulator that came with Lov_Tap, allowing transcription to occur under stimulation of blue light. We also included sfGFP which is our readout protein, allowing the used to know whether or not the light sensor was properly functioning. Near the end, once we had all the pieces we did a Gibson assembly to join our pieces. At that time we noticed that our blue light sensor had a point mutation that needed to be fixed. The point mutation was then fixed through several PCRs that retrieved two parts of the sensor without the mutation. Once those two parts were obtained, they were then fused together in the Gibson assembly along with being Gibson assembled together with the inverter and sfGFP. Future iGEM projects could be focused around detaching sfGFP as the output protein and attaching the light sensor to other parts of the e.coli gene, allowing light illuminated control of genetic pathways. | A blue light sensor (Lov_Tap BBa_K191003) was found in the registry and transformed to be used as one of our main components to create a functioning blue light sensor, activated at 470 nm wavelengths of light. The part taken from the registry was joined with a TetR inverter, since originally the blue light sensor repressed gene expression. The newly added TetR inverter then suppressed the regulator that came with Lov_Tap, allowing transcription to occur under stimulation of blue light. We also included sfGFP which is our readout protein, allowing the used to know whether or not the light sensor was properly functioning. Near the end, once we had all the pieces we did a Gibson assembly to join our pieces. At that time we noticed that our blue light sensor had a point mutation that needed to be fixed. The point mutation was then fixed through several PCRs that retrieved two parts of the sensor without the mutation. Once those two parts were obtained, they were then fused together in the Gibson assembly along with being Gibson assembled together with the inverter and sfGFP. Future iGEM projects could be focused around detaching sfGFP as the output protein and attaching the light sensor to other parts of the e.coli gene, allowing light illuminated control of genetic pathways. | ||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

Our solution was to design and build a software application for use on tablet devices that is able to shine light of different frequencies in different conformations (i.e. 96 well plate, petri dish) to enable controlled and reproducible characterization and testing of optogenetic pathways. The application that we designed can generate different wavelengths of light. To use the application we simply chose well or plates, and then chose wait time between flashes of colors in milliseconds of wait time and color intensities of each color from 0-100. The bacteria can then be grown overnight on top of the app. The app is currently available in the google play store for free and provides a convenient way for anyone interested in biological sciences to test their optogenetic systems. Because iGEM teams and labs will have a set budget, we hope that this tool becomes useful to all that want to pursue science. | Our solution was to design and build a software application for use on tablet devices that is able to shine light of different frequencies in different conformations (i.e. 96 well plate, petri dish) to enable controlled and reproducible characterization and testing of optogenetic pathways. The application that we designed can generate different wavelengths of light. To use the application we simply chose well or plates, and then chose wait time between flashes of colors in milliseconds of wait time and color intensities of each color from 0-100. The bacteria can then be grown overnight on top of the app. The app is currently available in the google play store for free and provides a convenient way for anyone interested in biological sciences to test their optogenetic systems. Because iGEM teams and labs will have a set budget, we hope that this tool becomes useful to all that want to pursue science. | ||

| - | |||

===Experimental Description=== | ===Experimental Description=== | ||

| Line 56: | Line 55: | ||

---- | ---- | ||

<h1 id='Results'>Results Summary <html><a href="#Background"><font size="3">[Top]</font></a></html></h1> | <h1 id='Results'>Results Summary <html><a href="#Background"><font size="3">[Top]</font></a></html></h1> | ||

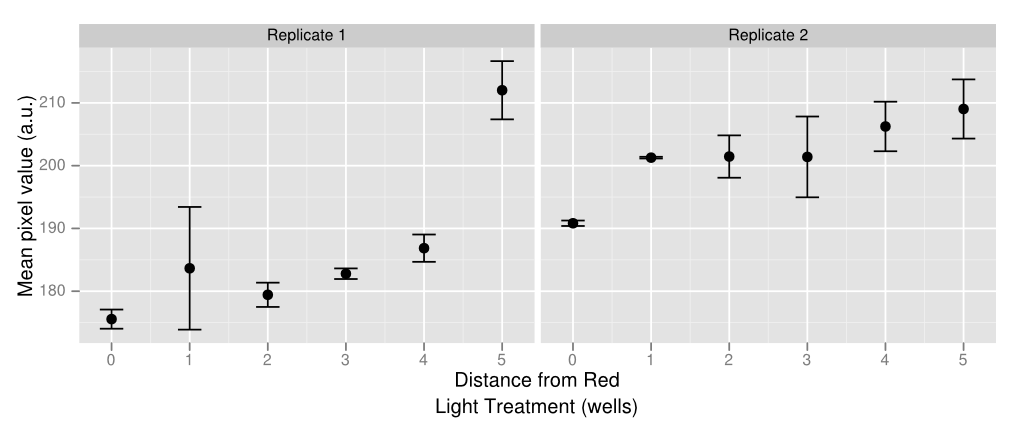

| - | When originally characterizing the light sensor, we found that bacteria left in darkness turned the controlled gene on equal to or more than the green light-illuminated plate. This is possibly because P<sub>cpcG2</sub> is leaky, or possibly because the natural conformation of the green light sensor is its upregulation form. Either way, our tests demonstrated that only the red light repressor was truly functional. When dealing with light leakage, we found that even decreasing the size of the light source didn't help as much as simply covering the light with the rubber stop.[[File:20120927 big dots cropped experimentwells | + | [[File:20120927 big dots cropped experimentwells resized.png|border|350px|left|thumb|Plate Experiment: Columns 1-5: constant exposure to green light. Columns 6-7: flashing red light. Columns 8-12: constant exposure to green light. Rows are replicates.]]When originally characterizing the light sensor, we found that bacteria left in darkness turned the controlled gene on equal to or more than the green light-illuminated plate. This is possibly because P<sub>cpcG2</sub> is leaky, or possibly because the natural conformation of the green light sensor is its upregulation form. Either way, our tests demonstrated that only the red light repressor was truly functional. When dealing with light leakage, we found that even decreasing the size of the light source didn't help as much as simply covering the light with the rubber stop.[[File:20120927 big dots cropped experimentwells firstroi ddply plot.png|border|350px|right|thumb|Image analysis of the plate experiment. The y axis is well darkness and the x axis is distance from the center of the plate. 0 is columns 6 and 7, 1 is 5 and 8, and so on. Wells closest to the center (red light, reduces lacZ expression) are lighter than wells that are farther away, indicating weaker gene expression.]] |

| - | |||

| - | + | As a proof of concept of both the light sensor and E. colight, we created a gradient of gene expression by making use of the light leakage. In two rows of a 96-well plate, we programmed all the well lights to display green constantly except for two lights in the middle, which periodically flashed red. The red light-induced downregulation of gene expression was demonstrated as the least amount of visible pigment was in the center of the gradient, and the greatest amount was at the ends. The well images were also put into ImageJ, which measured the average pixel value of each culture, as is shown in the graph on the right. The large uncertainty in the data is caused by uneven bacterial spreads in the agar, which can be solved by using soft agar. | |

| + | |||

---- | ---- | ||

<h1 id='Future'>Future Directions<html><a href="#Background"><font size="3">[Top]</font></a></html></h1> | <h1 id='Future'>Future Directions<html><a href="#Background"><font size="3">[Top]</font></a></html></h1> | ||

| - | |||

| - | + | We believe that light inducible gene expression represents a field that could be of great interest to synthetic biologists, and the iGEM community. The work we carried out this summer has laid a foundation on which we hope future teams can build, but there is much more than can be done. To that end, we are currently trying to standardize more the light sensors, and submit them to the registry so that they are readily available for all interested teams in the future. The light sensor used in this year's research appears to have a rather leaky promoter in our hands, leading to more transcription than we would normally expect in dark conditions. We think that the E.colight app developed over the summer could be used to address this problem. In 96 well plate experiments we noticed what appeared to be leakiness between wells. In order to carry out experiments using liquid cultures in the future, we may need to modify the assay plates. We are currently exploring a variety of options to accomplish this. For example, a suggestion was made to use a rubber adaptor with appropriately placed holes that would fit under a 96 well plate. Currently, the blue light sensor has not been characterized, and the only confirmation of a working sensor available right now are the sequencing files. We hope to continue to work with this sensor, testing and characterizing the sensor and seeking to fix any problems with the light sensor if problems are to be found. We hope to accomplish this kind of testing within the next couple of weeks. We would also like to work with the light sensors that we currently have in order to increase control of genetic pathways. The light sensors can also be attached to different genes in order to control production of certain substrates. Finally, Taking current light sensors available and applying them to e.coli is another aspiration of the Washington iGEM team. | |

| - | |||

| - | + | The main idea of creating a light activated system would be to control gene transcription, either producing a wanted substrate or breaking substrates down. One of the ways we would like to work with our light systems in the future is to optimize it to control metabolism or production of needed substrates in e.coli. Doing that will allow us to optimally control the growth of our bacteria, only allowing it to grow under a certain wavelength of light and metabolism being repressed in the absent of light and slowed down without the right wavelength of light illuminating the bacteria. That way, if someone becomes contaminated with the bacteria and goes out into the environment, the bacteria will ideally not be able to thrive there. Therefore, by preventing bacteria growth through optimized gene control we can prevent the spread of bacteria therefore protecting the environment from potential contamination with mutant strains. | |

| - | + | ||

| - | |||

| - | + | The app is readily available and can be downloaded onto any android OS system through the Google play store. Currently we have access to the tablet system with the app on it so we will want to use this app to further test our bacteria in the future to validate for functionality and to control genetic expression. | |

| - | |||

| - | [ | + | ---- |

| + | <h1 id='Parts'>Parts Submitted <html><a href="#Background"><font size="3">[Top]</font></a></html></h1> | ||

| - | + | [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K892800 BBa_K892800 '''LovTAP with reporter gene'''] | |

| + | LovTAP system, with inverter and sfGFP output. | ||

---- | ---- | ||

Latest revision as of 03:59, 4 October 2012

Optogenetics: A hands-free approach to protein regulation

Background

Bacterial metabolic pathways constitute a foundation on which to build biological processes that perform useful tasks such as the production of drugs, biofuels, or the degradation of harmful compounds. Often, to achieve an optimally tuned system, expression levels of each component must be varied over a wide range. The burgeoning field of optogenetics affords researchers the ability to control gene expression with light. In addition to being low cost, controlling of gene expression with light has a number of advantages over standard chemical methods of gene control. Among these are the ability to finely tune induction levels through changes in intensity, as well as the ability to quickly and completely remove the input. Further, many light-induced expression systems are reversible depending on the wavelength used for illumination. Thus one of the goals of the 2012 iGEM team is to implement a light inducible system which we hoped to apply to the tuning of multiple metabolic pathways. In addition, we wanted to make the tools to control optogenetic systems readily available and easier to access.

Our App: E. colight[Top]

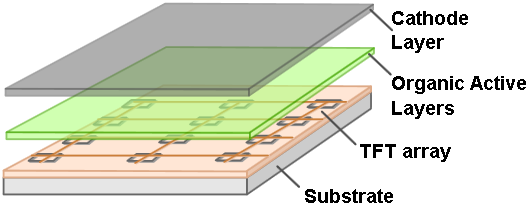

At the beginning of our project we wanted to make a system for high-specificity light control without the common problems such systems came with: High cost, difficult assembly, and very little reproducibility. With these goals in mind, we worked with Max Gelb to create E. colight.

E. colight was designed entirely from scratch in order to illuminate bacterial cultures with different types of light. The light source is on as either blue, green, or red. In the app, any given color of light can be shone between 0 and 60,000 milliseconds, which will illuminate the culture accordingly. Intensity of the light can be adjusted between 0 and 100%. All three colors are individually controllable, making high-specificity multichromatic tuning very easy.

The app has two settings which allow it to control bacterial cultures: One is its petri dish setting, which is a single light source made for a petri dish with an 8.5mm diameter. The other is a 96-well plate, which means it has 96 individually-controllable light sources, which lends the potential to run huge numbers of tests in tandem. The size of both the wells and the petri dish is flexible and can be adjusted between 0 and 100% of its original size.

Methods[Top]

Characterization of a light inducible protein expression system for the tuning of biological pathways

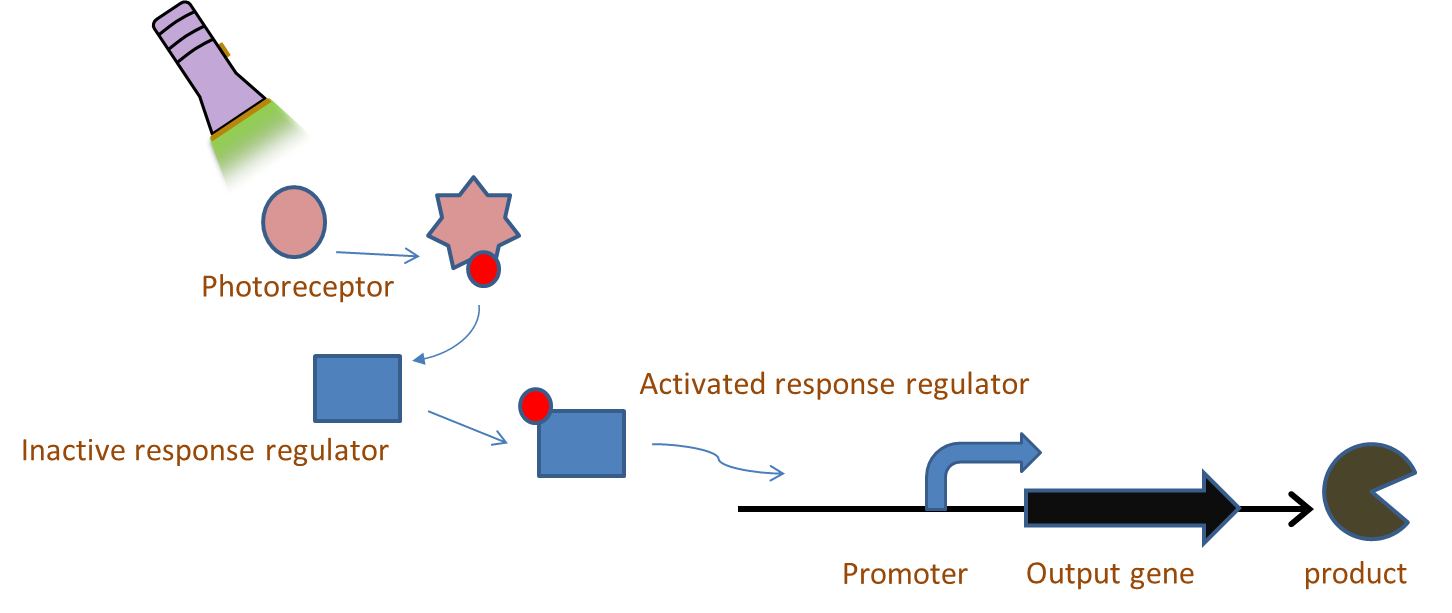

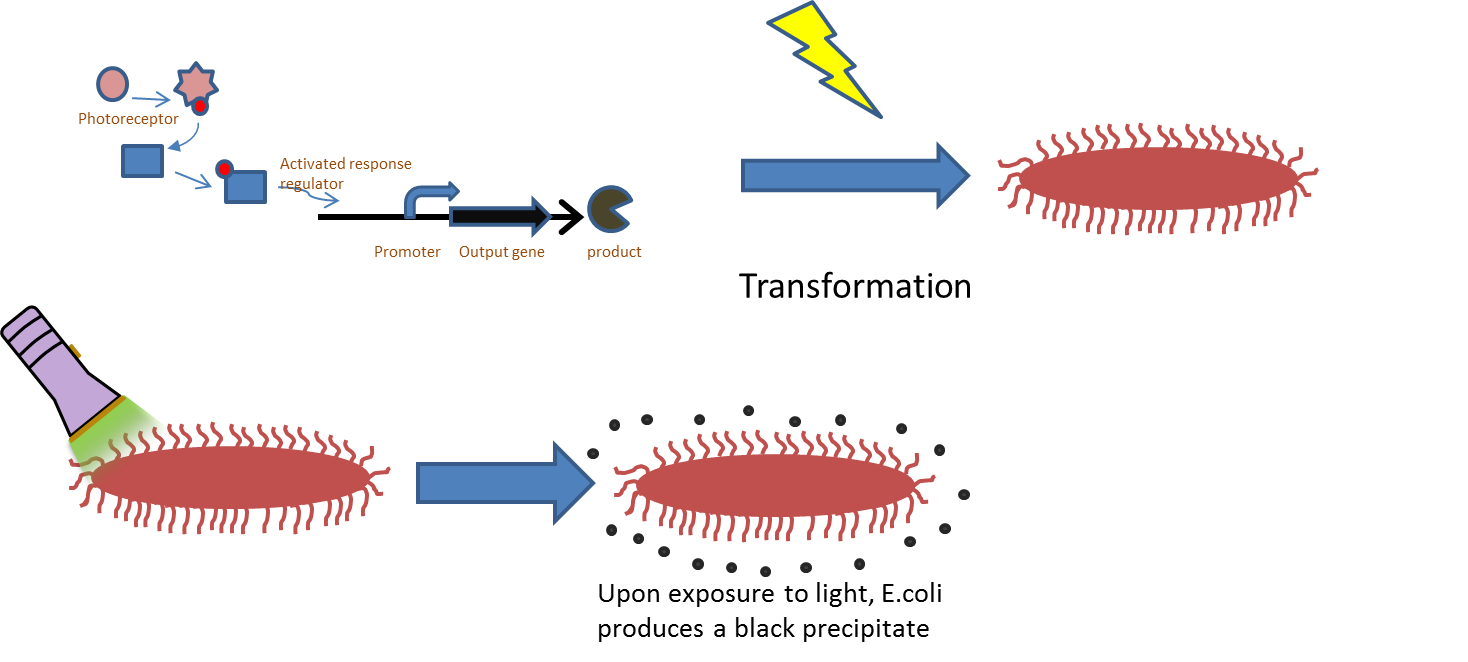

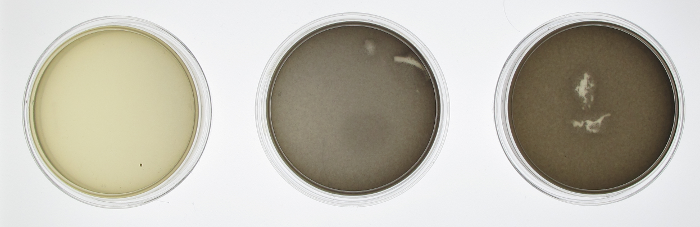

Chromatic tuning is based on light-induced protein interactions. The most basic of these systems is a monochromatic system, in which a specific wavelength of light changes a protein's conformation temporarily, causing it to interact differently with its environment. Our system involves the use of a photoreceptor CcaS attached to a chromophore and CcaR, a response regulator. The chromophore, when illuminated with green light (λ=535nm) will undergo a conformational change leading to autophosphorylation of the photoreceptor CcaS. Increased autophosphorylation leads to activation of the response regulator via phosphorylation. The activated response regulator will then bind to the promoter PcpcG2, activating transcription and producing beta-galactosidase. Beta-galactosidase will cleave the S-gal, creating a black precipitate and allowing us to know visually that our light sensor is working. Red light (λ=672nm), on the other hand, changes the protein conformation such that it resists phosphorylation, thus not binding to the promoter and not allowing gene expression. Any gene placed after the promoter can be theoretically controlled by the exposure of λ=535nm and λ=637nm light to the system.

A blue light sensor (Lov_Tap BBa_K191003) was found in the registry and transformed to be used as one of our main components to create a functioning blue light sensor, activated at 470 nm wavelengths of light. The part taken from the registry was joined with a TetR inverter, since originally the blue light sensor repressed gene expression. The newly added TetR inverter then suppressed the regulator that came with Lov_Tap, allowing transcription to occur under stimulation of blue light. We also included sfGFP which is our readout protein, allowing the used to know whether or not the light sensor was properly functioning. Near the end, once we had all the pieces we did a Gibson assembly to join our pieces. At that time we noticed that our blue light sensor had a point mutation that needed to be fixed. The point mutation was then fixed through several PCRs that retrieved two parts of the sensor without the mutation. Once those two parts were obtained, they were then fused together in the Gibson assembly along with being Gibson assembled together with the inverter and sfGFP. Future iGEM projects could be focused around detaching sfGFP as the output protein and attaching the light sensor to other parts of the e.coli gene, allowing light illuminated control of genetic pathways.

Building Optogenetic Tools

The current swath of tools available to illuminate bacterial cultures in a controlled manner often necessitate the purchase of specialized equipment or materials. Further, devices must often be both constructed, and fully characterized by the researcher prior to conducting any experiments to ensure reproducibility. To circumvent these problems, we sought to develop an application whose accessibility played off of modern technological conveniences. In recent years, mobile technology has become increasingly ubiquitous. Each year sees the release of many new tablets, phones, and small computers, including some that are relatively cheap. Tablets are excellently-sized, cost-effective tools for use with bacterial cultures.

Our solution was to design and build a software application for use on tablet devices that is able to shine light of different frequencies in different conformations (i.e. 96 well plate, petri dish) to enable controlled and reproducible characterization and testing of optogenetic pathways. The application that we designed can generate different wavelengths of light. To use the application we simply chose well or plates, and then chose wait time between flashes of colors in milliseconds of wait time and color intensities of each color from 0-100. The bacteria can then be grown overnight on top of the app. The app is currently available in the google play store for free and provides a convenient way for anyone interested in biological sciences to test their optogenetic systems. Because iGEM teams and labs will have a set budget, we hope that this tool becomes useful to all that want to pursue science.

Experimental Description

E. coli was transformed with pJT122 and pJT106b, which contained the lacZ gene, the green light sensor, and the system's chromophores.[3] In order to characterize the genes, we put them through three experiments: An assay of pigment concentration based on bacterial concentration, an assay of pigment concentration based on absorbed light, and a test of light leakage between wells.

In order to test the functionality of the green light activator and red light repressor, we plated the same cells onto three petri dishes. One petri dish was incubated in green light, one in red light, and one in total darkness for 15 hours. The dish exposed to red light demonstrated very strong downregulation, while the dish exposed to green light showed strong upregulation.

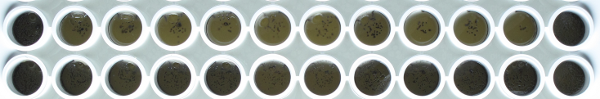

When performing characterization tests on 96-well plates, we found that bacteria over a predominantly-green well but near predominantly-red wells had drastically decreased gene expression compared to predominantly-green wells that weren't near red light. After repeating trials, we decided this was due to light leaking from one well to another. An LED spreads light in all directions, unlike a laser which focuses only in a single area. This leak was causing the green light sensors to switch conformation and repress gene output, which meant that our tuning could lead to imprecise results. In order to compensate for this, we added a feature to the app, and made use of a rubber gasket. Hoping to keep our tools all electronic, we added a well-size modulator to the app in order to increase the gap spaces between wells and hopefully decrease the amount of light that moved from its generative well to another well. The rubber gasket was our physical fix, and simply involved placing a 96-well rubber cover on top of the app so that only light moving upwards would pass though.

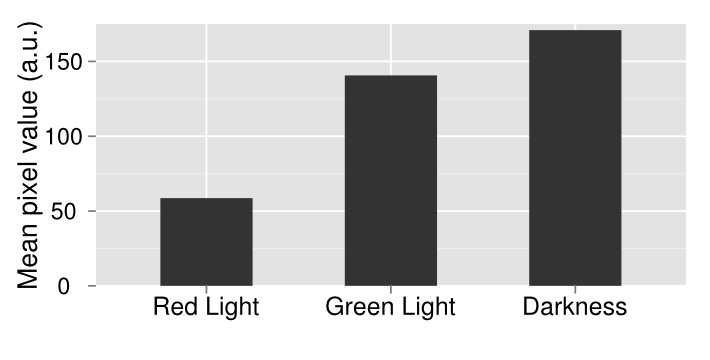

In order to make more precise comparisons between data, we used ImageJ to quantify lacZ expression. In ImageJ, the images were converted to grayscale, and the average black pixel density was calculated for each plate or well. The quantified data gives a more careful look at our results, and adds details to results that cannot be told apart by the naked eye.

Results Summary [Top]

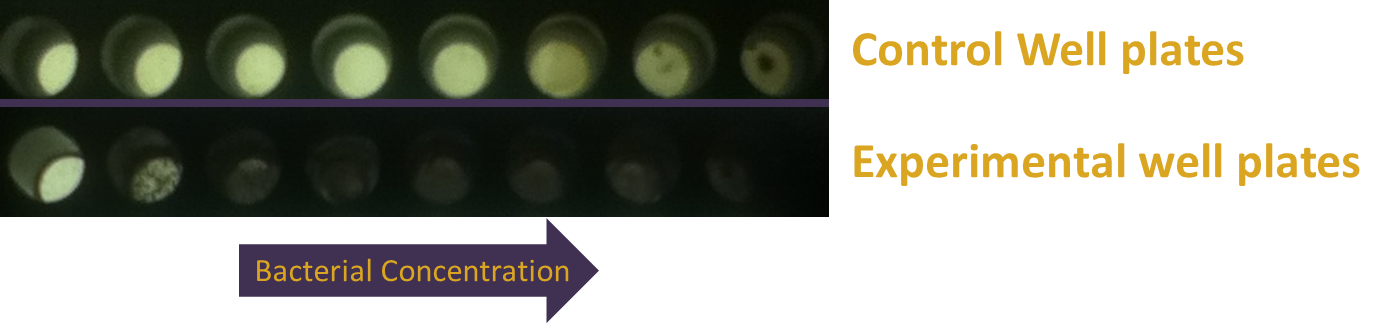

As a proof of concept of both the light sensor and E. colight, we created a gradient of gene expression by making use of the light leakage. In two rows of a 96-well plate, we programmed all the well lights to display green constantly except for two lights in the middle, which periodically flashed red. The red light-induced downregulation of gene expression was demonstrated as the least amount of visible pigment was in the center of the gradient, and the greatest amount was at the ends. The well images were also put into ImageJ, which measured the average pixel value of each culture, as is shown in the graph on the right. The large uncertainty in the data is caused by uneven bacterial spreads in the agar, which can be solved by using soft agar.

Future Directions[Top]

We believe that light inducible gene expression represents a field that could be of great interest to synthetic biologists, and the iGEM community. The work we carried out this summer has laid a foundation on which we hope future teams can build, but there is much more than can be done. To that end, we are currently trying to standardize more the light sensors, and submit them to the registry so that they are readily available for all interested teams in the future. The light sensor used in this year's research appears to have a rather leaky promoter in our hands, leading to more transcription than we would normally expect in dark conditions. We think that the E.colight app developed over the summer could be used to address this problem. In 96 well plate experiments we noticed what appeared to be leakiness between wells. In order to carry out experiments using liquid cultures in the future, we may need to modify the assay plates. We are currently exploring a variety of options to accomplish this. For example, a suggestion was made to use a rubber adaptor with appropriately placed holes that would fit under a 96 well plate. Currently, the blue light sensor has not been characterized, and the only confirmation of a working sensor available right now are the sequencing files. We hope to continue to work with this sensor, testing and characterizing the sensor and seeking to fix any problems with the light sensor if problems are to be found. We hope to accomplish this kind of testing within the next couple of weeks. We would also like to work with the light sensors that we currently have in order to increase control of genetic pathways. The light sensors can also be attached to different genes in order to control production of certain substrates. Finally, Taking current light sensors available and applying them to e.coli is another aspiration of the Washington iGEM team.

The main idea of creating a light activated system would be to control gene transcription, either producing a wanted substrate or breaking substrates down. One of the ways we would like to work with our light systems in the future is to optimize it to control metabolism or production of needed substrates in e.coli. Doing that will allow us to optimally control the growth of our bacteria, only allowing it to grow under a certain wavelength of light and metabolism being repressed in the absent of light and slowed down without the right wavelength of light illuminating the bacteria. That way, if someone becomes contaminated with the bacteria and goes out into the environment, the bacteria will ideally not be able to thrive there. Therefore, by preventing bacteria growth through optimized gene control we can prevent the spread of bacteria therefore protecting the environment from potential contamination with mutant strains.

The app is readily available and can be downloaded onto any android OS system through the Google play store. Currently we have access to the tablet system with the app on it so we will want to use this app to further test our bacteria in the future to validate for functionality and to control genetic expression.

Parts Submitted [Top]

[http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K892800 BBa_K892800 LovTAP with reporter gene]

LovTAP system, with inverter and sfGFP output.

Sources [Top]

[1]http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/96/AMOLED_en.svg

[2]Levskaya, A. et al. Synthetic biology: Engineering Escherichia coli to see light. Nature 438, 441–442 (2005).

[3]Tabor, J. J., Levskaya, A. & Voigt, C. a Multichromatic control of gene expression in Escherichia coli. Journal of molecular biology 405, 315–24 (2011).

"

"