Team:MIT/Results

From 2012.igem.org

(Adding Modeling to Sensing, yay!) |

|||

| Line 363: | Line 363: | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

Modeling of mRNA secondary structure was done using <a href="http://nupack.org">NUPACK</a>. Strand displacement reaction kinetics were simulated using <a href="http://lepton.research.microsoft.com/webgec/">Visual GEC</a>. | Modeling of mRNA secondary structure was done using <a href="http://nupack.org">NUPACK</a>. Strand displacement reaction kinetics were simulated using <a href="http://lepton.research.microsoft.com/webgec/">Visual GEC</a>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </p><p> | ||

| + | We used Visual GEC extensively to develop and test computational models of the strand displacement systems we designed, including the mRNA sensor, the NOT gate (see <a href = "https://2012.igem.org/Team:MIT/Results#Not_Gate_in_vitro">Processing</a>), and a hypothetical NOT sensor which combines the functionalities of both. This enabled us to optimize the properties of our systems, and examine their kinetics, before performing <i>in vitro</i> experiments with actual DNA. | ||

| + | </p><p> | ||

| + | The syntax of Visual GEC code is straightforward: indicate when to plot and what to plot, indicate kinetic rates, and indicate allowable reactions. The software then calculates how reactions will proceed. While <a href = "">Visual DSD</a>, a similar tool which is specialized for simulating DNA strands, would also have worked for our purposes, Visual GEC gave finer control of reaction rates. The kinetic constants were based on work published by Lulu Qian and Erik Winfree (<a href = "http://www.sciencemag.org/content/332/6034/1196/suppl/DC1">Science 2011</a>). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <h2>Simple mRNA Sensor</h2> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The first task is to create a simulation of an mRNA sensor. The strands involved in the design are the mRNA input itself, the ROX:quencher fluorescent reporter complex, the annealed gate:output complex, and the fuel strand which accelerates the reaction rate. The visual GEC code describing this system is below. | ||

| + | img1 | ||

| + | </p><p> | ||

| + | This compiles to a visual depiction of the reaction network, and simulating a kinetic run outputs a prediction of the level of each product. | ||

| + | img2 | ||

| + | </p><p> | ||

| + | We can then specifically compare the levels of the output molecule -- which is fluorescence of the unquenched ROX-bound RNA -- and observe the difference in output level for different concentrations of input. | ||

| + | img3 | ||

| + | </p><p> | ||

| + | <i>green curve: 9 nanomolar (i.e. 90%) input strand | ||

| + | red curve: 1 nM (10%) input strand | ||

| + | both run with 100nM fuel strand, 12 nM ROX:quencher reporter complex, 10 nM gate:output complex</i> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </p><p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h2>NOT mRNA Sensor</h2> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Next, we designed a NOT mRNA sensor, in the hope that creating an effective NOT sensor this could simplify potential circuits by removing the need to cascade a NOT gate with an mRNA sensor. | ||

| + | </p><p> | ||

| + | The NOT sensor includes the familiar mRNA strand, fluorescent reporter complex, gate:output complex, and fuel strands. In addition, it contains a new strand called the "sensor" strand, which displaces the gate:output but is competitively bound by mRNA. Thus, the presence of an mRNA strand inhibits the sensor, preventing output signal. The absence of an mRNA strand allows the sensor strand to displace the gate:output signal, creating a fluorescent signal. This creates NOT logic. These reactions are described in the Visual GEC code. | ||

| + | img4 | ||

| + | </p><p> | ||

| + | Running this code, we can compare the output that results from various concentrations of mRNA input. The shape of this transfer function reveals the NOT logic. The NOT sensor system was designed with a steep dropoff as opposed to a steady gradient, so that the circuit as a whole would behave more reliably. | ||

| + | img5 | ||

| + | </p><p> | ||

| + | <i>In vitro</i> tests of the functionality of the NOT sensor strands are in progress. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

</p> | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

Revision as of 03:15, 1 October 2012

RNA Strand Displacement In Vitro

Previously:

In 2011, Lulu Qian and Erik Winfree, researchers at Caltech, published a paper entitled "Scaling Up Digital Circuit Computation with DNA Strand Displacement Cascades." This paper demonstrated how scalable logic circuits based on DNA strand displacement are capable of processes as complicated as the square root function. See our motivation page for more details.

MIT iGEM 2012:

Before our team attempted to bring the mechanism of strand displacement into an in vivo context, we first decided to assay strand displacement in vitro using RNA. We used 2'-O-methylated RNA strands, which had not been shown to undergo strand displacement in vitro. Before creating our own constructs, we adapted sequences from the Qian/Winfree paper to RNA.

MIT iGEM Foundational Experiment:

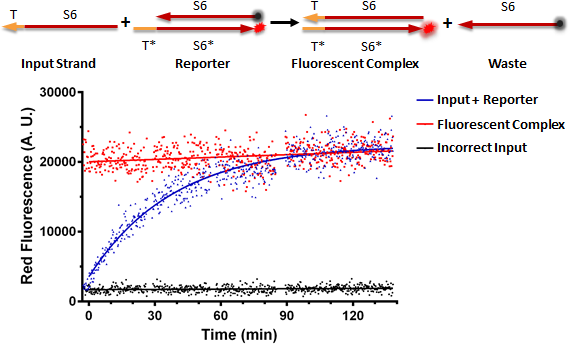

Figure A shows a foundational in vitro RNA strand displacement experiment that was performed on a plate reader. The negative control, in black, is a well that received only an annealed reporter complex. The bottom strand of this complex is the gate strand, T*-S6*, with the 3' end tagged with the ROX fluorophore. The top strand of the complex is the output strand, S6. This is complementary to the S6* domain of the gate strand. The 5' end is tagged with the Iowa Black RQ quencher, which absorbs the ROX fluorescence; thus, when the two strands of the reporter are annealed, no fluorescence should be observed. The positive control, in red, is the input strand, T-S6, annealed to the gate strand, T*-S6* tagged with ROX. This is what we would expect the product of a strand displacement reaction to look like. We can see that in the experimental well, when the input is present, it can bind to the exposed T* domain of the reporter and displace the output strand, yielding a fluorescent complex and a waste strand.

Figure A

Nucleic Acid Delivery

In order to implement RNA strand displacement cascades in vivo, we first demonstrated our ability to deliver nucleic acids to mammalian cells. We have achieved the delivery of plasmid DNA, single-stranded modified RNA and double-stranded modified RNA to mammalian cells through both lipofection and nucleofection.

(1) Delivery of Plasmid DNA to Mammalian Cells

Through the Gateway method, we have assembled many promoter-gene constructs as detailed on our Parts Page. After construction of the plasmid, we deliver the plasmid DNA to Mammalian Cells through the use of transient transfection, lipofection with Lipofectamine 2000 reage

Images of eYFp/mKate transfection from Confocal

(2) Delivery of 2'-O-Me RNA to Mammalian Cells

For the purpose of our experiments, RNA oligos with chemical modifications that confer significant overall stability and increase in Tm is necessary to prevent spontaneous dissociation and rapid degradation by nucleases under in vivo conditions. One form of chemically modified RNA, 2’O-Methyl RNA, is a naturally occurring and nontoxic RNA variant found in mammalian ribosomal RNAs and transfer RNAs. These modified oligos are in most respects similar to RNA, but the 2' O-Methyl modification increases overall stability as the -OH functional group at the 2' position is replaced with a -OMe group, which can't perform cleavage of the RNA backbone. In addition to significant nuclease stability, the modification seem to confer increases in Tm, which minimizes the chance of the RNA strands dissociating upon introduction to a cellular environment. (CITATION NEEDED!)

Therefore, we need the ability to deliver 2’-O-Methyl RNA to mammalian cells.

The movie below shows HEK293 cells expressing constitutive eYFP with a 2'-O-Methyl RNA strand labeled with ROX (5-carboxy-x-rhodamine) on the 3' end. As time passes, the complex/vesicles are uptaken by the cell, releasing their payload resulting in whole cell fluorescence. Each frame is 5 minutes, movie encompasses 200 minutes in 9 seconds.

Delivery of ROX-labeled 2'-O-Methyl RNA into HEK cells.

Time point images taken at t = 0, 2, 3, and 4 hours post-transfection. Images taken at 10X on Zeiss microscope.

Time point images taken at t = 0, 2, 3, and 4 hours post-transfection. Images taken at 10X on Zeiss microscope.

Once we demonstrated ability to deliver 2'-O-Me RNA to mammalian cells, we ran optimization experiments to optimize the ratio of 2'-O-Me RNA delivered to RNAiMAX (transfection reagent used).

Figure of transfection efficiency with dsALEXA

Caption

(3) Inducible Control of Protein Expression

The microscopy images above show a brightfield view, the blue filter and the red filter. TagBFP serves as our transfection marker, indicating that cells have taken in foreign DNA. In the red channel, we show that as you increase the concentration of DOX, more cells fluoresce red.

The figure above was generated by transfecting the inducible expression system and varying the concentration of DOX across 16 different data points, and then analyzing using flow cytometry. We demonstrate that as you increase the concentration of DOX, the mean fluorescence increases. At high concentrations of DOX, we eventually see saturation of signal.

Delivery of Plasmid DNA which transcribes short RNA Inputs

In Vivo RNA Strand Displacement

We believe in RNA strand displacement as the ultimate processing medium for mammalian cellular circuits. In order to achieve strand displacement in vivo, we went through five different experimental designs after confirming the ability to deliver and produce many different types of oligos in vivo.

Strategy 1: Lipofectamine 2000 Transfection of RNA version of Reporter from Winfree/QIan 2011 Paper

Our first strategy to implement RNA strand displacement in vivo was to adapt the DNA sequences of inputs, gates and reporters from the Qian/Winfree, "Scaling Up Digital Circuit Computation with DNA Strand Displacement Cascades," 2011 Science Paper to 2’-O-Methyl RNA strands to transfect into mammalian cells. See our Motivation page for more details.

In the first foundational experiment, HEK293 (Human Embryonic Kidney cells) were used that constitutively expressed a yellow fluorescent protein (eYFP) in order to be easily visible in microscopy images. 200,000 HEK293 cells were seeded into four wells of a 24 well plate in supplemented DMEM without phenol red pH indicator. The negative control well did not receive any RNA. As a transfection reagent, each well received 1 uL of Lipofectamine 2000. The positive control well received 5 pmol of a gate strand tagged with a ROX fluorophore annealed to an input strand, to act as a product of a strand displacement reaction. The scrambled input well received 5 pmol annealed double stranded reporter with quenched ROX along with a 5 pmol of an input strand containing the correct toehold domain but the incorrect binding domain. Therefore, when both constructs are inside the cell, a strand displacement reaction should not occur, and the fluorophore remains quenched. In the final well, correct input, the cells received 5 pmol of double stranded reporter as well as 5 pmol of an input strand with the correct toehold domain and hybridization domain. Accordingly, we should expect that the toehold of the input strand binds to the complementary exposed toehold on the double stranded reporter, and will branch migrate and effectively kick off the output strand of the reporter that is tagged with a quencher. Therefore, the fluorophore will no longer be quenched, yielding red fluorescence.

Refer to this diagram to identify labeled strands

Refer to this diagram to identify labeled strands

In the negative control well, 200,000 HEK293+eYFP cells are healthy and adherent. In the positive control well, we see localized red fluorescence in the form of vesicles as well as distributed, whole cell red fluorescence. In the scrambled input well, we see red vesicles as well as red whole cell fluorescence. In the correct input well, we see only whole cell red fluorescence.

Strategy 2: Switch Transfection reagent to RNAiMAX

From the first foundational experiment, we observed localized red fluorescence in vesicles as well as whole cell fluorescence. This indicates that our reporter complex is either melting, being degraded, being recognized by a specific enzyme etc as well as the reporter is coming apart inside of the lipofectamine vesicles. We researched better transfection reagents for double stranded RNA, and found that Lipofectamine RNAiMAX is designed specifically for the delivery of double stranded RNA, whereas Lipofectamine 200 is specifically designed for the delivery of plasmids.

Once we received the new transfection reagent, we set up experiments similar to the initial experiment but with an optimized protocol for RNAiMAX (See Materials and Methods).

Caption for images from 6/14 experiment with old reporter and RNAiMAX where we do not see fluorescent vesicles anymore however we do still see fluorescent cells in the control and experimental wells

Caption for images from 6/14 experiment with old reporter and RNAiMAX where we do not see fluorescent vesicles anymore however we do still see fluorescent cells in the control and experimental wells

Strategy 3: Tag RNA strand with an Alexa Fluorophore to act as a transfection marker

Strategy 4: Create DNA plasmids driving transcription of RNA inputs, while transfecting RNA Reporter

Strategy 4: Nucleofect RNA reporter, RNA inputs

[Strategy 5]: Redesign RNA Reporter

Sensing Overview

We designed, modeled and tested an mRNA sensor that interfaces with RNA-based strand displacement circuitry.

Sensing Design

We imposed the following criteria on our mRNA sensor design:

- orthogonality

- easy integration with strand displacement circuits

- ability to amplify a signal

- ease of sensor generation

The way we implemented this sensor is by considering the mRNA sequence and choosing within it two consecutive abstract domains: the toehold and the sensing domains. These domains mirror the toehold and recognition domains in strand displacement, so provide an interface to any strand displacement circuit. Specifically, the chosen toehold and sensing domain will then directly interface with an intermediate gate:output complex using toehold-mediated strand displacement, with signal amplification achieved using a fuel strand.

Illustration of an mRNA sensor. A toehold region in the mRNA can bind to the toehold on a gate:output complex. Branch migration can then occur, resulting in a free output signal. Using fuel, the mRNA can be released from the gate, enabling it to react with another gate:output complex.

However, this abstraction needs to take into account the secondary structure of mRNA: some regions are more accessible (less basepairing), while others are strongly basepaired and thus unavailable to be directly sensed by mechanisms that involve basepairing to the mRNA (Kertesz et al. 2007).

Software rendered secondary structure of eBFP2 (BBa_K779300) showing various secondary structure elements (e.g. stems and loops)

Much work has been done to generate these secondary structures computationally (see nupack.org), and to find accessible regions predicted to be miRNA binding sites within mRNAs (e.g. PITA). We leveraged these algorithms to identify potential toehold and sensing domains within mRNAs by looking for regions with different levels of accessibility.

Once suitable domains have been chosen using modeling of the secondary structure, we can rank them by their orthogonality to other transcribed RNAs. These sequences are available in online databases (e.g. mRNA data for HEK 293 cells). For strand displacement, the rate limiting step is the binding of a strand to a gate:output complex using the toehold. After this step, the process of strand displacement is sensitive to nucleotide mismatches, with early mismatches being more disruptive than later mismatches (Qian et al. 2011). Thus, we can use a weighted Hamming distance between a candidate domain and every subsequence in the transcriptome. This method is similar to identifying orthogonal sequences for protein-DNA interactions as previously published (Silver et al. 2012).

Care has to be taken to make sure that sensors in a circuit are orthogonal as well, but the same method can be applied to any sequences that are introduced into a cell.

Four highlighted domains of eBFP2 with various secondary structures we chose to sense. Blue-filled circles represent toehold nucleotides, green-filled nucleotides represent sensing domain nucleootides. The border of a nucleotide's circle represents the probability of the nucleotide being in the given state (red - very likely, blue - very unlikely). These are closeups of the mRNA structure above.

Sensing Modeling

Modeling of mRNA secondary structure was done using NUPACK. Strand displacement reaction kinetics were simulated using Visual GEC.

We used Visual GEC extensively to develop and test computational models of the strand displacement systems we designed, including the mRNA sensor, the NOT gate (see Processing), and a hypothetical NOT sensor which combines the functionalities of both. This enabled us to optimize the properties of our systems, and examine their kinetics, before performing in vitro experiments with actual DNA.

The syntax of Visual GEC code is straightforward: indicate when to plot and what to plot, indicate kinetic rates, and indicate allowable reactions. The software then calculates how reactions will proceed. While Visual DSD, a similar tool which is specialized for simulating DNA strands, would also have worked for our purposes, Visual GEC gave finer control of reaction rates. The kinetic constants were based on work published by Lulu Qian and Erik Winfree (Science 2011).

Simple mRNA Sensor

The first task is to create a simulation of an mRNA sensor. The strands involved in the design are the mRNA input itself, the ROX:quencher fluorescent reporter complex, the annealed gate:output complex, and the fuel strand which accelerates the reaction rate. The visual GEC code describing this system is below. img1This compiles to a visual depiction of the reaction network, and simulating a kinetic run outputs a prediction of the level of each product. img2

We can then specifically compare the levels of the output molecule -- which is fluorescence of the unquenched ROX-bound RNA -- and observe the difference in output level for different concentrations of input. img3

green curve: 9 nanomolar (i.e. 90%) input strand red curve: 1 nM (10%) input strand both run with 100nM fuel strand, 12 nM ROX:quencher reporter complex, 10 nM gate:output complex

NOT mRNA Sensor

Next, we designed a NOT mRNA sensor, in the hope that creating an effective NOT sensor this could simplify potential circuits by removing the need to cascade a NOT gate with an mRNA sensor.The NOT sensor includes the familiar mRNA strand, fluorescent reporter complex, gate:output complex, and fuel strands. In addition, it contains a new strand called the "sensor" strand, which displaces the gate:output but is competitively bound by mRNA. Thus, the presence of an mRNA strand inhibits the sensor, preventing output signal. The absence of an mRNA strand allows the sensor strand to displace the gate:output signal, creating a fluorescent signal. This creates NOT logic. These reactions are described in the Visual GEC code. img4

Running this code, we can compare the output that results from various concentrations of mRNA input. The shape of this transfer function reveals the NOT logic. The NOT sensor system was designed with a steep dropoff as opposed to a steady gradient, so that the circuit as a whole would behave more reliably. img5

In vitro tests of the functionality of the NOT sensor strands are in progress.

Sensing In vitro studies

We chose 4 domains in eBFP2 with various predicted secondary structure properties to test out in vitro. eBFP2 (BBa_K779300) mRNA was produced by PCRing on a T7 promoter and terminator (TODO: link to primers?). The resulting template was then used for in vitro transcription (see Protocols TODO: link). After purification and quantification on a NanoDrop 1000, the transcribed mRNA, corresponding gate:outputs and fuel strands along with a fluorescent reporter were added to wells in a 96-well plate and the fluorescence was measured on a plate reader (See TODO: link to protocol).

For proof-of-concept studies we chose DNA as nucleic acid for the gate:output, fuel, and reporter complexes, as these results will mirror results with RNA-based strands, as shown by foundational experiments. However, the thermodynamics, kinetics and steady states will be different between DNA and RNA strands. We expect mRNA to produce less output than a corresponding DNA input mimic (comprising of just the toehold and sensing domains) in the same amount.

Results indicate that there is a difference between the 4 domains we chose, and that the output signal from mRNA is less than the signal from DNA mimics.

In vitro results from a DNA-based mRNA sensor. Graphed here is the fold increase in RFU - comparing the pre-input fluorescence to the fluorescence after (TODO) hours. Baseline (light gray) reflects no input. DNA input mimic (dark gray) is a DNA oligonucleotide with the same sequence as the toehold and sensing domains in mRNA (black).

Comparing mRNA as an input to DNA as an input. Graphed here is the ratio of fold increase fluorescence comparing mRNA inputs to DNA inputs. This indicates the possible completion level due to mRNA inputs. As described above, we expect this to be <1.

Not Gate in vitro

Figure 1 - DNA molecules that constitute the NOT GATE

The original strand displacement paper demonstrated AND and OR gates, but did not include NOT gates. We successfully designed and built a strand displacement NOT gate in vitro, expanding the computational structures possible with strand displacement.

The design of our NOT gate is in Figure 1 above, where a letter with a '*' depicts a complementary domain to the one denoted by the letter alone. We arrived to this design after iterating through numerous other ideas, trying each time to reduce the number of molecules involved and their complexity.

To understand the behavior of this NOT gate, it can be useful to consider two extreme cases: no input and saturation-level input.

When the input is not present, molecule B can bind reversibly with A (by partially displacing a1) and reversibly with C (by partially displacing c2). When B binds with C, molecule D finishes the job and fully kicks c2 off of c. c2 then triggers the readout E by irreversibly displacing e2 from e1. Meanwhile, D also frees B from c1, making B catalytic and allowing it to react with more C molecules, amplifying the output. Therefore we will see high fluorescence.

When the input is present in high concentration, B binds to a2, partially displacing a2 from a1. The input then binds to a1, completing what B started by fully and irreversibly separating a2 and a1. This step was inspired by the mechanism of the cooperative hybridization (Cooperative Hybridization of Oligonucleotides,David Yu Zhang,JACS 2011). Since B is stuck with a2, it can no longer displace c2 from C, and the readout pathway described above cannot continue. Consequently e2 cannot be displaced from the readout. Therefore we will see no fluorescence.

Experimental result for the in vitro NOT GATE where the output fluorescence is normalized to the highest value of the NOT GATE transfer function and the total volume for each level of input was 100ul.

The relative concentration of A with respect of input and B is extremely important. Indeed if the concentration of A is too low the cooperative hybridization between A , B and a high concentration of input can be slow, consequently B can displace c2 from C, that is, we would have a high level of output although the input level is high. On the other hand if the concentration of A is too high, even without the presence of input, B will continuously reversibly bind with A. Consequently B will not displace c2 from C and therefore we would not see a high level of output when the level of input is low.

In addition to the relative concentration of the different components another important point is the absolute concentration of them. This is mainly due to how the cooperative hybridization works. Indeed the reactants are three and the products two, consequently at low concentration the reactants are more favorable in the reaction whereas at high concentration the products will be more favorable.

Our strategy consisted first in finding the right concentration to let the cooperative hybridization works and then we tuned the concentration of A to find the right trade of between the interaction of A, input and B when the input is high and the interaction of A and B when the input is low.

Not Gate modeling

Figure 2 - NOT GATE transfer function in vitro and by simulation using the software Visual DSD

The NOT GATE modeling was performed using Visual DSD, in Fig2 the overlay of the simulated transfer function and the in vitro one where the basal fluorescence this time was subtracted.

The simulation helped us to find the right trade off, as mentioned before, in the choice of the relative concentration of A with to respect of B and input.

For the rate constant we used the one from the article "Scaling Up Digital Circuit Computation with DNA Strand Displacement Cascades, Lulu Qian and Erik Winfree, Science, 2011".

Hammerhead Ribozymes

Red: mKate, Blue: mKate-Hammerhead, Cyan: Hammerhead-mKate. Overall, inserting a hammerhead ribozyme sequence into mRNA decreases the red fluorescent output.

Red: mKate, Blue: mKate-Hammerhead, Cyan: Hammerhead-mKate. Overall, inserting a hammerhead ribozyme sequence into mRNA decreases the red fluorescent output.

Decoys and Tough Decoys (TuDs)

We wanted something that would provide a tight double repression system with a very distinct change between on and off. The TuDs and Decoys design were originally inspired by the “Vectors expressing efficient RNA decoys achieve the long-term suppression of specific microRNA activity in mammalian cells,” paper. We copied their designs and wanted to reproduce the results in our lab. To do so, we ordered TuDs and decoys both with and without bulges. The bulges are designed to disrupt RISC complex activity; something which degrades short RNA like our decoys in the cell.

Sources: http://nar.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2009/02/17/nar.gkp040.abstract

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9695408

"

"