Contents[hide] |

The Problem

Producing complex therapeutic proteins often requires biosynthesis in mammalian cells. This protein expression method presents several issues. Our project focuses on one: getting a mammalian cell to express the desired protein when we want it to. Currently, bioreactors in industry rely heavily on small signaling molecules to get the cells to respond. The time it takes for these molecules to diffuse through the cell culture medium and their subsequent purification from the final product are the primary limitations. To allow for finer control over gene expression, our project studied the implementation of two different light-induced genetic (or optogenetic) switches. Both enable tight regulation of gene expression and eliminate the problem of removing signaling molecules during the final purification of the synthesized protein.

Many of the proteins synthesized for therapeutic purposes can also be toxic to the cells that produce them. Precise control of gene expression in these cases is crucial to the viability of the cells being cultivated. Small signaling molecules aren't ideal for these purposes but light is instantaneous and easy to modulate.

The Simple Switch

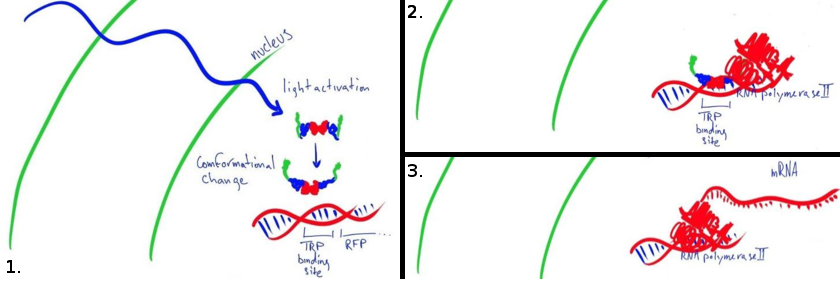

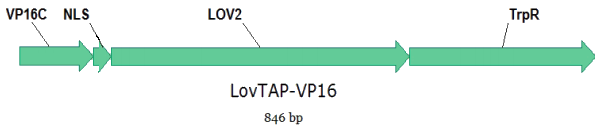

The first switch we studied is an untested fusion protein designed to act as a light-induced transcriptional activator in mamallian cells. The LovTAP-VP16 protein consists of a Lov2 domain (from Avena Sativa) a Trp repressor (from bacteria) and a VP16 transactional activating domain (from the Herpes simplex virus). A first version of this fusion protein was developed at the University of Chicago and later characterized and used as a bacterial repressor by the EPFL 2009 iGEM team. The protein binds to a Trp promoter after undergoing a conformational change when exposed to light. By fusing the LovTAP protein to a viral promoter, the idea was to turn the protein into a light activated DNA binding protein. When the Trp promoter is bound to the LovTAP-VP16 protein, the viral promoter on the C terminal recruits RNA polymerase II to the site and favors the transcription of the reporter gene next to the Trp promoter.

This pathway is simple and light activation of LovTAP-VP16 results in direct activation of transcription. However, there are some major obstacles in this approach. The protein needs to be localized in the nucleus, bind tightly to DNA and remain attached long enough to activate transcription.

For this system, we will be using a DsRed readout to characterize the speed and efficiency of transcription by quantifying fluorescence output.

The Complex Switch

In addition to LovTAP switch, we will be realizing another, more complex, melanopsin-based light switch developed by Fussenegger et al. In this switch, a light-sensitive membrane bound protein, melanopsin, is inserted to trigger a signalling cascade. The melanopsin opens calcium channels in the cell which activates the NFAT pathway. By inserting a readout gene next to an NFAT promoter, we can promote its expression by triggering the release of calcium with light. In our expriments we used eGFP as our readout protein for the same reasons DsRed was used in the LovTAP-VP16 experiments. This optogenetic switch takes advantage of an already existing mammalian pathway and limits the potential flaws related to promoting transcription once the pathway is activated. However, calcium is a broad effector and can have unintended consequences. Different cell types also react differently to calcium influx and this approach might not be generalizable. Fussenegger's team were successful in promoting expression in HEK (human embryo kidney) cells, and we will also try to get the pathway to work in CHO cells and compare the results to the work done in HEK cells.

Constructs

All of the following plasmids have a resistance to ampicillin to allow culture in bacteria. Please contact us for the exact sequence and annotation for each of the used plasmids.

- pHY42 : pHCMV-melanopsin-pASV40

This vector was provided to us by Prof. Martin Fussenegger. It contains human melanopsin with a human cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter followed by a bovine growth hormone (bGH) polyadenylation signal and an antibiotic resistance gene for neomycin.

- NFAT response vector: pGL4.30-eGFP

We cloned the enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) in to replace luciferase in the original vector. This vector contains an NFAT response element followed by eGFP, a poly-A signal and a gene of resistance to hygromycin.

[http://www.promega.com/resources/protocols/product-information-sheets/a/pgl430-vector-protocol/ pGL4.30]

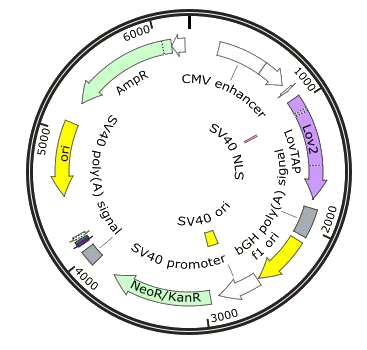

- LovTAP expression vector: pcDNA3.1(+)-LovTap-VP16

LovTAP-VP16 was inserted into the MCS in front of a CMV promoter and a Kozak sequence and is followed by a bGH polyadenylation signal. The vector also contains resistance for hygromycin which makes the creation of a stable cell line possible.

[http://products.invitrogen.com/ivgn/product/V79020 pcDNA3.1(+)]

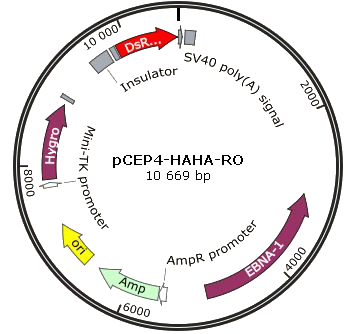

- LovTAP readout vector: pCEP4-Trp-dsRed

A Trp promoter and DsRed were cloned into the MCS. The constitutive promoter was also excised. The final plasmid contains an SNS insulator from a sea urchin, followed by the TetR binding domain for LovTAP-VP16 fixation, an SV40 poly-A signal and a gene for hygromycin resistance.

[http://products.invitrogen.com/ivgn/product/V04450 pCEP4]

Proteins

LovTAP-VP16

LovTAP-VP16 is the name of the protein our light switch is based on. But it has never been expresed before and, therefore, there is no literature telling us under what conditions it works or whether it works at all. It's a fusion protein between LovTAP, which is itself a fusion protein, and an activation domain from VP16, a viral transcription factor.

In this construct, we don't want any kind of steric interaction between LovTAP and VP16, since that might alter the functionality of one or both parts, whereas we just want VP16 to be transported by LovTAP. To allow this, a linker might be needed to physically separate the domains. Since LovTAP-VP16 has to be in the nucleus of the cell to work, the minimal linker would be a 7 residues long Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS) from the virus SV40, with the amino acid sequence PKKKRKV.

In order to check visually if a longer linker would be needed, we put together the existing crystal structures of the domains LovTAP-VP16 consists of: LOV2, TrpR, NLS and VP16.

LovTAP

In a paper published in 2008 [http://www.pnas.org/content/105/31/10709.abstract], Strickland et al. propose to modify the protein TrpR in order to make it controllable by light. This is done by fusing it to a light-sensitive protein, the plant phototropin LOV2 (Light-Oxygen-Voltage), whose sensitivity to blue light is conferred by the ligand chromophore flavin mononucleotide (FMN). The fusion is done in a way that ensures that both domains share a common α-helix, which would create a sort of lever that could transfer the conformational changes in light-activated LOV2 towards TrpR, triggering its activation.

How does it work?

Allosteric regulation

In a protein, generally an enzyme, an allosteric site is any part of the protein other than the active site.

Allosteric regulation of a protein consists in modifying its properties by interacting with an allosteric site. One example would be the regulation in the tryptophan (Trp) operon, a group of genes studied in E.Coli that are required for the synthesis of the amino acid tryptophan. The expression of these genes can be blocked by the homodimeric protein tryptophan repressor (TrpR), by binding the operator of the operon. The TrpR repressing function is only active when tryptophan is bound to its allosteric sites, i.e. it blocks the production of tryptophan when the concentration of tryptophan is high.

TrpR

Tryptophan Repressor protein, from E.Coli. Homodimer whose dimeric conformation changes when the amino acid tryptophan binds it, increasing the TrpR's affinity for the Trp operator palindromic sequence CGTACTAGTTAACTAGTACG.

LOV2

LOV2 photoreceptor domain, part of the phototropin 1 protein from Avena sativa (oat). Excited mainly at approximately 390, 450 and 470 nm, and emits around 500 nm (Kasahara et al, 2002). When photoexcited, the terminal Jα-helix tends to undock from the main body of the protein, this being the signaling step.

VP16C

VP16 is a transcriptional activator used by Herpex simplex. VP16C is an activation domain in VP16, corresponding to residues 456 to 490 (Hendrik et al, 2005). It has already been used in fusion transcription factors, such as GAL4-VP16 (Sadowski et al, 1988).

DsRed

This is a commercially available destabilized red fluorescent protein, available from [http://www.clontech.com/CH/Products/Fluorescent_Proteins_and_Reporters/Fluorescent_Proteins_by_Name/DsRed-Monomer_Fluorescent_Protein Clontech]. In comparison to the normal red fluorescence protein (RFP), it has a lower half-life, so is more suited for observation of dynamical processes, such as modification of protein expression after illumination.

Melanopsin

A standard mouse melanopsin receptor was supplied by Fussenegger et al (2011). Its sequence can be found [http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q9QXZ9 here].

eGFP

Enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP), standard read-out protein commonly used in the laboratory.

Future Work

Characterizing and troubleshooting the activating characteristics of the LovTAP-VP16 protein should be a priority in getting the simple switch system to work. It's still not clear whether or not it is localized in the nucleus and properly binds DNA with the additional VP16 promoter domain.

A nuclear extract with western blotting or immunofluorescence techniques could be used to localize the protein. If the localisation of the protein isn't correct, the nuclear localisation signal might need modification or extension.

A chromatin immunoprecipitation assay could be used to verify the binding characteristics of the LovTAP protein in the case where it is localised in the nucleus but still doesnt work.

If the protein can bind DNA and is localized in the nucleus, a different promoter/linker combination could be used ahead of VP16 to initiate transcription.

Other verions of LovTAP which respond better to light have also been characterized by Strickland et al.

[http://www.nature.com/nmeth/journal/v7/n8/full/nmeth.1473.html Improvement of Lov domain based photoswitches]

By using an improved version of the protein with a more dynamic response to light we could improve the DNA binding response to light and activation of transcription.

By using a positive feedback loop, the difference between the dark and the light state can be increased [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/%28SICI%291521-2254%28200003/04%292:2%3C107::AID-JGM91%3E3.0.CO%3B2-E/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Curr%20Opin%20Cell%20Biol&rft.atitle=Transcriptional%20repression%20in%20development&rft.volume=8&rft.spage=358&rft.epage=364&rft.date=1996&rft.aulast=Gray&rft.aufirst=S&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary] which would make detecting the signal easier.

Lastly, the creation of stable cell lines for either of our expression systems would make sense for a longer term project. The original experiment conducted by Fussenegger et al. used antibiotic resistance to select cells that had integrated the transfected DNA. With a homogenous population of cells, it would be easier to characterize the efficiency of the system in use.

With our transient expression experiment for both switches, we had heterogenous cell populations. The efficiency of our transfections was around 30% and each cell integrated our vectors at different places in the genome. The constitutive levels of LovTAP-VP16 or melanopsin proteins as well as the accesibility of the readout and promoter on the genome varied within the population of transfected cells.

It could be that our proteins behave the way we would like them to in a few cells among the many that were transfected, but that most of the time integration of the transfected DNA is weak and expression levels are too low.

"

"