Team:Cambridge/Project/Standardised Outputs

From 2012.igem.org

(→Standardised Outputs) |

(→Ratiometrica and use of bacterial luciferase - Standardised Outputs) |

||

| (13 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Template:Team:Cambridge/CAM_2012_TEMPLATE_HEAD_PROJECT}} | {{Template:Team:Cambridge/CAM_2012_TEMPLATE_HEAD_PROJECT}} | ||

| - | = | + | = Ratiometrica and use of bacterial luciferase - Standardised Outputs= |

[[File:principles1.png|right|400px|thumb|Nature's approach to analyzing different chemical parameters. Note the cross talk between the sensory cascades, which renders the system highly unpredictable.]] | [[File:principles1.png|right|400px|thumb|Nature's approach to analyzing different chemical parameters. Note the cross talk between the sensory cascades, which renders the system highly unpredictable.]] | ||

| - | The use of biosensors | + | ''To skip to a more detailed discussion of our construct design, please click <html><a href="https://2012.igem.org/Team:Cambridge/Project/DesignProcess#Ratiometric" style="color:#000066">here</a></html>'' |

| + | |||

| + | ''To skip to characterisation, please click <html><a href="https://2012.igem.org/Team:Cambridge/Project/Results#Ratiometric" style="color:#000066">here</a></html>.'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The use of biosensors has one main advantage over traditional, electronic sensors, which is the diversity of chemical signals to which these finely tuned nanomachines can respond to. The ability of the cells to integrate and process information sensed in this way is powerful, but presently the complexity of the metabolic pathways used by cells for this confounds attempts at synthetic in vivo information processing. Until we have a far more complete picture of the interactions between cellular components that allow information processing (something which may be provided in the future by the field of Systems biology), the use of electronic circuits will remain a far more powerful and simple means of processing such information. | ||

In order to transfer such information to a computer would require a biological - electronic interface. This implies that the bacteria would send a message of some sort, which will be detected by an electronic sensor. Many different cell types, each containing a complement of genes suitable for detecting a particular substance, would be used in different spatial locations. Separation of the different genes into different cellular compartments would prevent crosstalk between the different sensory cascades, improving the reliability and predictability of the constructs produced. | In order to transfer such information to a computer would require a biological - electronic interface. This implies that the bacteria would send a message of some sort, which will be detected by an electronic sensor. Many different cell types, each containing a complement of genes suitable for detecting a particular substance, would be used in different spatial locations. Separation of the different genes into different cellular compartments would prevent crosstalk between the different sensory cascades, improving the reliability and predictability of the constructs produced. | ||

| Line 11: | Line 16: | ||

[[File:principles2.png|left|750px|thumb|Our approach to analyzing different chemical parameters.]] | [[File:principles2.png|left|750px|thumb|Our approach to analyzing different chemical parameters.]] | ||

| - | In order to best implement these principles, we decided that every biosensor should be coupled to a standard output with its own response curves, to suit the customer's needs. Decoupling the culture/analyte solution from the detection system (e.g. an electronic one) would be a good idea as otherwise the behaviour of the electrode under different conditions might affect the results. Therefore we chose to use light as the signal transducer. This left us with a choice between biofluorescence and bioluminescence. | + | In order to best implement these principles, we decided that every biosensor should be coupled to a standard output with its own response curves, to suit the customer's needs. Decoupling the culture/analyte solution from the detection system (e.g. an electronic one) would be a good idea as otherwise the behaviour of the electrode under different conditions might affect the results. Therefore we chose to use light as the signal transducer. This left us with a choice between biofluorescence and bioluminescence. |

Whilst fluorescent proteins have been characterised in far greater detail than luciferases, part of the broader aim of the project is for our kit to be as affordable as possible. And given that the equipment to detect the emission spectra of luciferases is cheaper, we decided that a quantitative measurement of bioluminescence was a better option. | Whilst fluorescent proteins have been characterised in far greater detail than luciferases, part of the broader aim of the project is for our kit to be as affordable as possible. And given that the equipment to detect the emission spectra of luciferases is cheaper, we decided that a quantitative measurement of bioluminescence was a better option. | ||

| - | One of the greatest problems we seek to overcome in this project is that of consistent readouts. As is always the case with biology, predictability in our biosensing equipment was going to be an issue. To normalise for cell density productivity, it was decided that a ratiometric output would be absolutely necessary if the output from our biosensors was to be meaningful. Drawing on work done by James Brown and the Haseloff lab into reliable, predictable and quantitative ratiometric measurements using fluorescent proteins, we decided to use these principles as the basis of our work with luciferase. We also decided that, as a side experiment and proof of concept, we would attempt to achieve meaningful ratiometric outputs with fluorescent proteins that could be measured with an (all too expensive!) plate reader. | + | One of the greatest problems we seek to overcome in this project is that of consistent readouts. As is always the case with biology, predictability in our biosensing equipment was going to be an issue. To normalise for cell density productivity, it was decided that a ratiometric output would be absolutely necessary if the output from our biosensors was to be meaningful. Drawing on work done by James Brown and the Haseloff lab into reliable, predictable and quantitative ratiometric measurements using fluorescent proteins, we decided to use these principles as the basis of our work with luciferase. We also decided that, as a side experiment and proof of concept, we would attempt to achieve meaningful ratiometric outputs with fluorescent proteins that could be measured with an (all too expensive!) plate reader. |

| - | [[File:CFP+YFP ratiometric construct.png| | + | [[File:CFP+YFP ratiometric construct.png|700px|thumb|The construct made in the pJS 130 vector for the ratiometric measurement of IPTG concentrations with fluorescent proteins.]] |

On the luciferase side of things, after a fairly deep trawl through the literature, an OFP-luciferase fusion was found where the emission spectra appeared sufficiently distinguishable from that of the normal bacterial luciferase (a fairly distinctive blue) that it could be measured using simple photo-resistors and coloured filter gels. The emission spectra of the OFP/luciferase fusion is shown below: | On the luciferase side of things, after a fairly deep trawl through the literature, an OFP-luciferase fusion was found where the emission spectra appeared sufficiently distinguishable from that of the normal bacterial luciferase (a fairly distinctive blue) that it could be measured using simple photo-resistors and coloured filter gels. The emission spectra of the OFP/luciferase fusion is shown below: | ||

| Line 25: | Line 30: | ||

The construct that we designed is shown below: | The construct that we designed is shown below: | ||

| - | [[File:lux construct Cam.png| | + | [[File:lux construct Cam.png|700px|thumb|center|The construct made in the pJS130 vector and made by DNA 2.0 for the ratiometric measurement of IPTG concentrations with luciferase.]] |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | A more detailed description of the design process of these constructs can be found <html><a href="https://2012.igem.org/Team:Cambridge/Project/DesignProcess#Ratiometric" style="color:#000066">here</a></html>, and characterisation and other data for them can be found <html><a href="https://2012.igem.org/Team:Cambridge/Project/Results#Ratiometric" style="color:#000066">here</a></html>. | ||

<br style='clear: both;' /> | <br style='clear: both;' /> | ||

{{Template:Team:Cambridge/CAM_2012_TEMPLATE_FOOT}} | {{Template:Team:Cambridge/CAM_2012_TEMPLATE_FOOT}} | ||

Latest revision as of 20:28, 26 September 2012

Ratiometrica and use of bacterial luciferase - Standardised Outputs

To skip to a more detailed discussion of our construct design, please click here

To skip to characterisation, please click here.

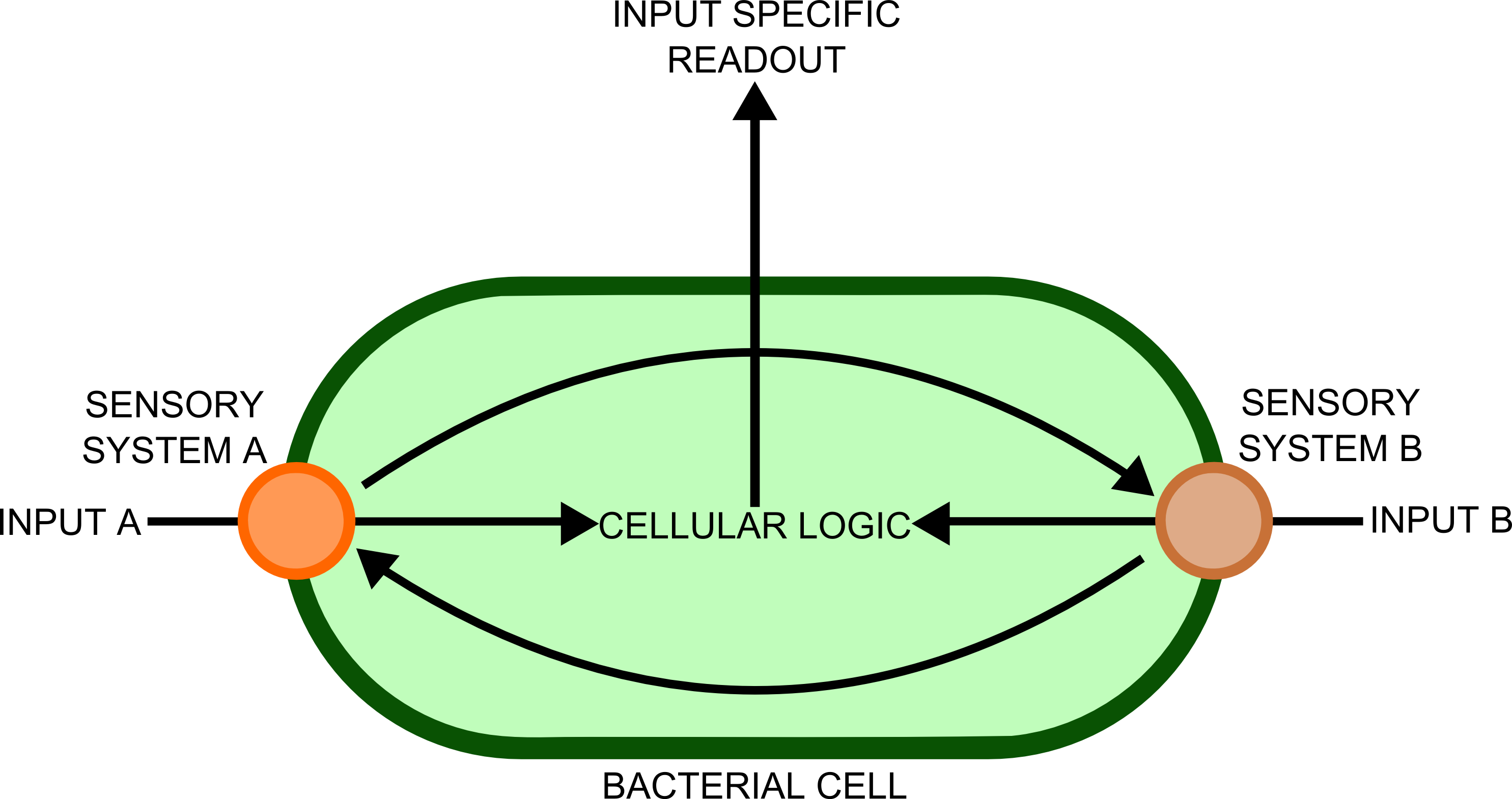

The use of biosensors has one main advantage over traditional, electronic sensors, which is the diversity of chemical signals to which these finely tuned nanomachines can respond to. The ability of the cells to integrate and process information sensed in this way is powerful, but presently the complexity of the metabolic pathways used by cells for this confounds attempts at synthetic in vivo information processing. Until we have a far more complete picture of the interactions between cellular components that allow information processing (something which may be provided in the future by the field of Systems biology), the use of electronic circuits will remain a far more powerful and simple means of processing such information.

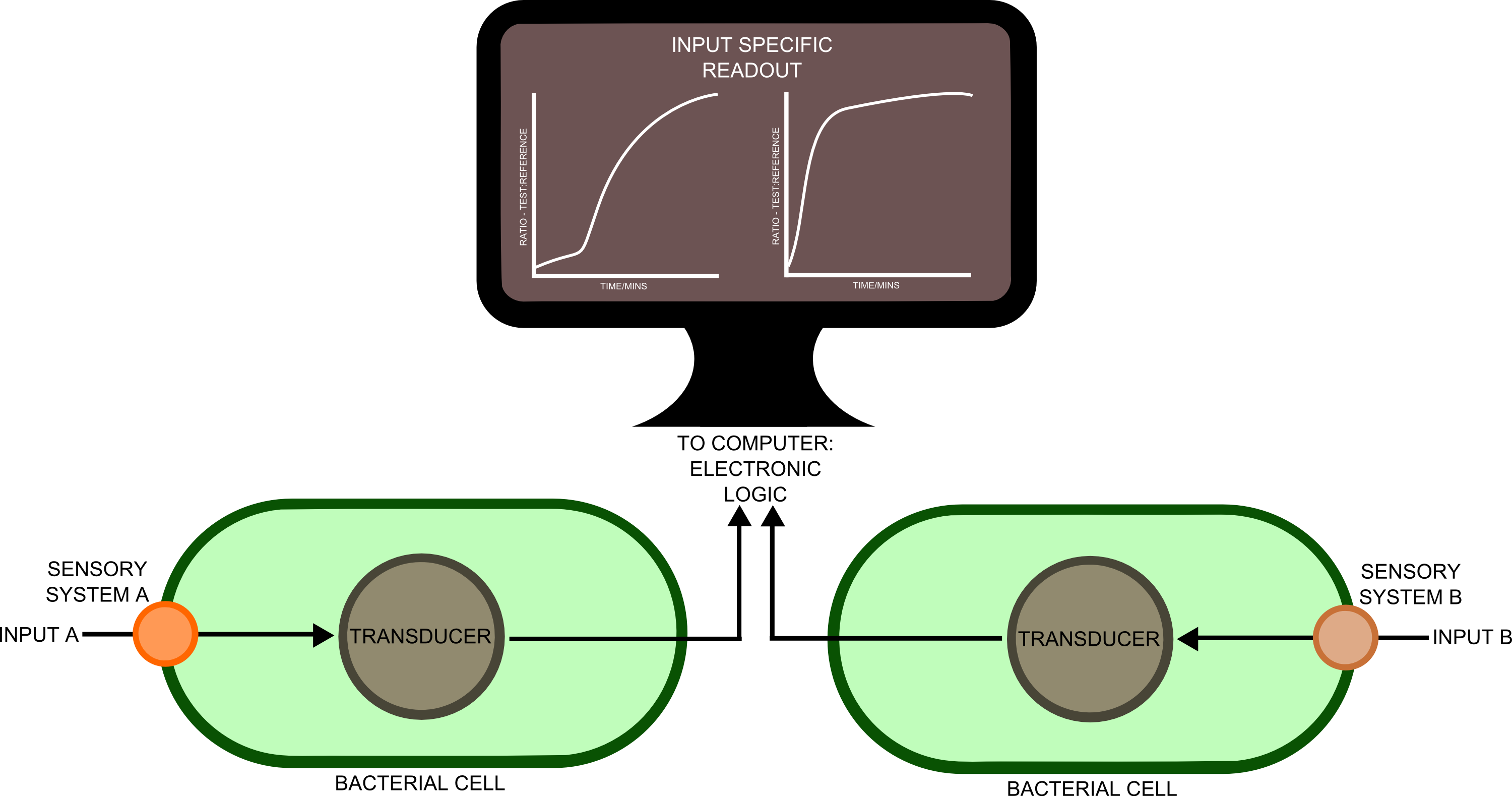

In order to transfer such information to a computer would require a biological - electronic interface. This implies that the bacteria would send a message of some sort, which will be detected by an electronic sensor. Many different cell types, each containing a complement of genes suitable for detecting a particular substance, would be used in different spatial locations. Separation of the different genes into different cellular compartments would prevent crosstalk between the different sensory cascades, improving the reliability and predictability of the constructs produced.

In order to best implement these principles, we decided that every biosensor should be coupled to a standard output with its own response curves, to suit the customer's needs. Decoupling the culture/analyte solution from the detection system (e.g. an electronic one) would be a good idea as otherwise the behaviour of the electrode under different conditions might affect the results. Therefore we chose to use light as the signal transducer. This left us with a choice between biofluorescence and bioluminescence.

Whilst fluorescent proteins have been characterised in far greater detail than luciferases, part of the broader aim of the project is for our kit to be as affordable as possible. And given that the equipment to detect the emission spectra of luciferases is cheaper, we decided that a quantitative measurement of bioluminescence was a better option.

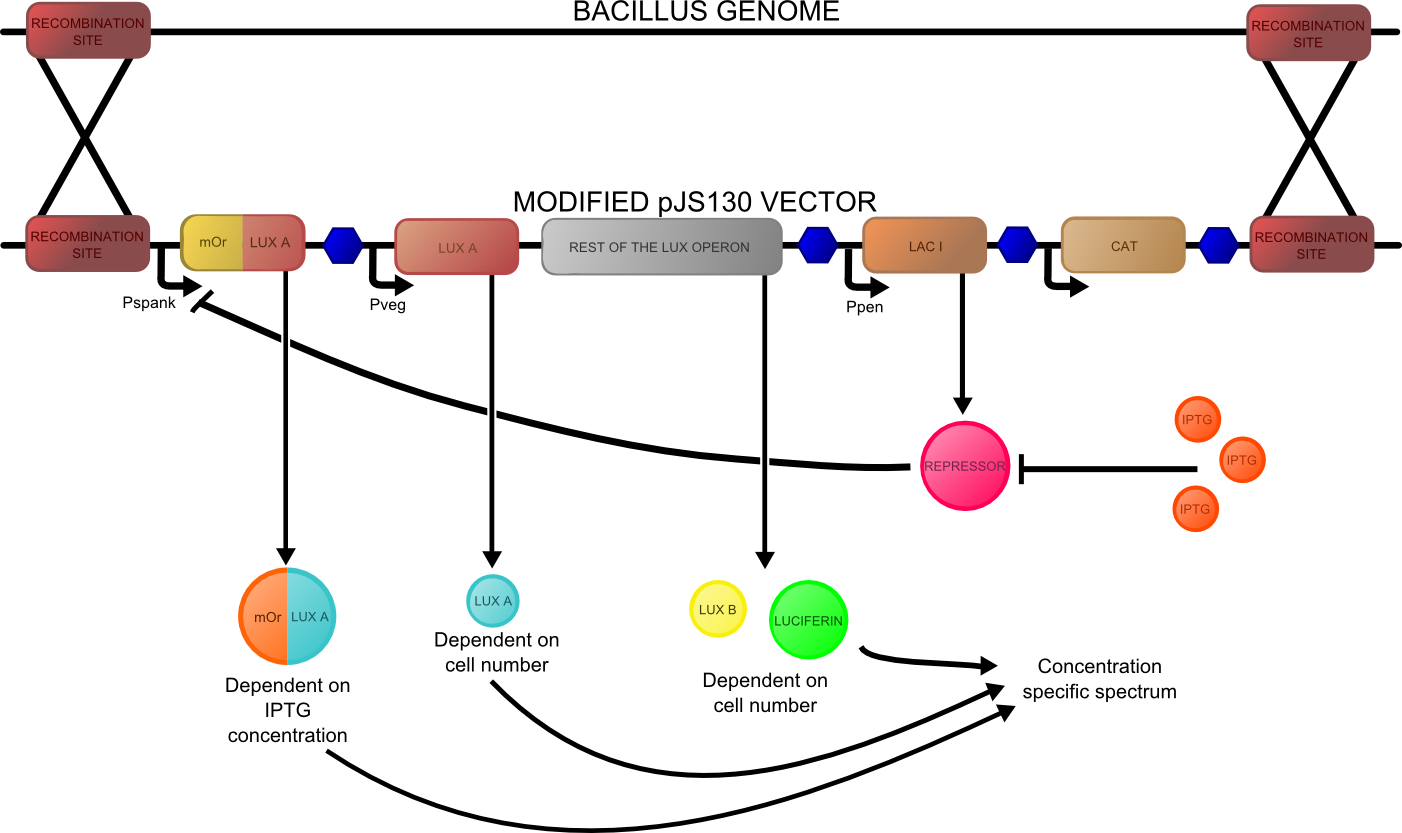

One of the greatest problems we seek to overcome in this project is that of consistent readouts. As is always the case with biology, predictability in our biosensing equipment was going to be an issue. To normalise for cell density productivity, it was decided that a ratiometric output would be absolutely necessary if the output from our biosensors was to be meaningful. Drawing on work done by James Brown and the Haseloff lab into reliable, predictable and quantitative ratiometric measurements using fluorescent proteins, we decided to use these principles as the basis of our work with luciferase. We also decided that, as a side experiment and proof of concept, we would attempt to achieve meaningful ratiometric outputs with fluorescent proteins that could be measured with an (all too expensive!) plate reader.

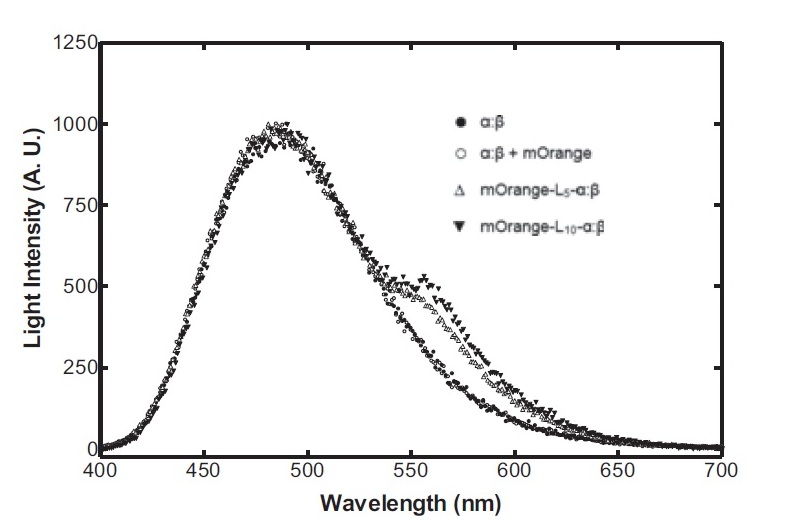

On the luciferase side of things, after a fairly deep trawl through the literature, an OFP-luciferase fusion was found where the emission spectra appeared sufficiently distinguishable from that of the normal bacterial luciferase (a fairly distinctive blue) that it could be measured using simple photo-resistors and coloured filter gels. The emission spectra of the OFP/luciferase fusion is shown below:

The construct that we designed is shown below:

A more detailed description of the design process of these constructs can be found here, and characterisation and other data for them can be found here.

"

"