Team:LMU-Munich/Germination Stop

From 2012.igem.org

| Line 138: | Line 138: | ||

| style="width: 70%;background-color: #EBFCE4;" | | | style="width: 70%;background-color: #EBFCE4;" | | ||

{| | {| | ||

| - | |[[File:LMU SuicideSwitch grafik.png| | + | |[[File:LMU SuicideSwitch grafik.png|624px|center]] |

|- | |- | ||

| style="width: 70%;background-color: #EBFCE4;" | | | style="width: 70%;background-color: #EBFCE4;" | | ||

Revision as of 21:37, 25 September 2012

The LMU-Munich team is exuberantly happy about the great success at the World Championship Jamboree in Boston. Our project Beadzillus finished 4th and won the prize for the "Best Wiki" (with Slovenia) and "Best New Application Project".

[ more news ]

GerminationSTOP

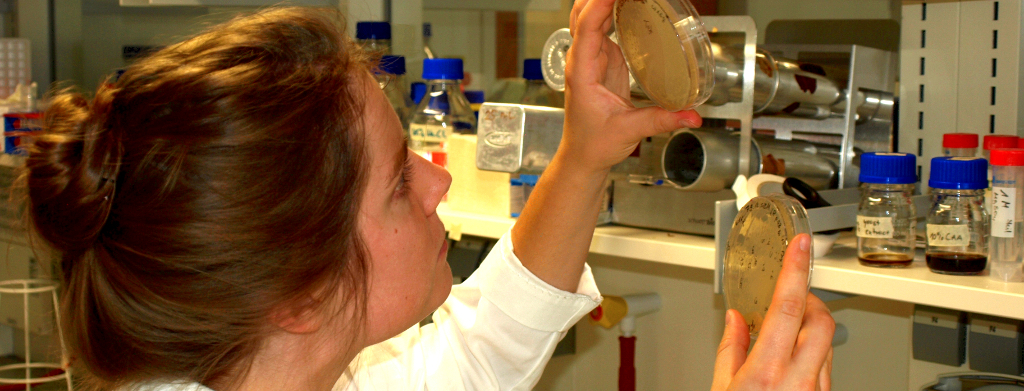

The goal of this subproject was to yield Sporobeads which are safe (unable to germinate) and consistently functional (maintain their spore shape and structure). To achieve this, we sought to remove the germination capability of our spores, while keeping their necessary structural functions intact.

Two approaches were used to achieve this:

- Knock out genes that are involved in germination.

- Suicide switch: Toxin production by vegetative cells if germination knockout fails and spores manage to germinate.

How does Germination Work?

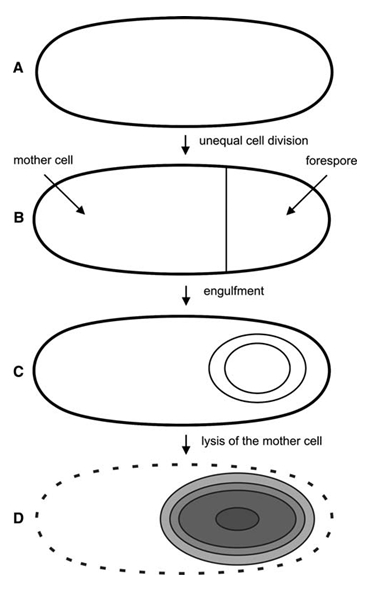

The Bacillus life cycle can include both classic division, and also reproduction by sporulation and spore germination. In response to starvation of nutrients (including carbon, nitrogen, or phosphorus) or in response to peptides secreted by other cells which signal too high of population densities to cells, Bacillus cells form spores in a process called sporulation. The “mother” cell forms the endospore within its own cell membrane. The endospore contains its DNA in the spore core, which is protected by several layers of coats. The outermost layer is the spore crust. The spore is very dry, and contains a substance called dipicolinic acid (DPA), which is replaced with water when the spore germinates. Until the spore hydrates and swells out of its protective coats, it is resistant to a wide variety of environmental stressors, including UV radiation, toxic chemicals, freezing, high heat, dessication, and pH extremes. This resistance to stressors allows the spore to survive until conditions are good for growth.

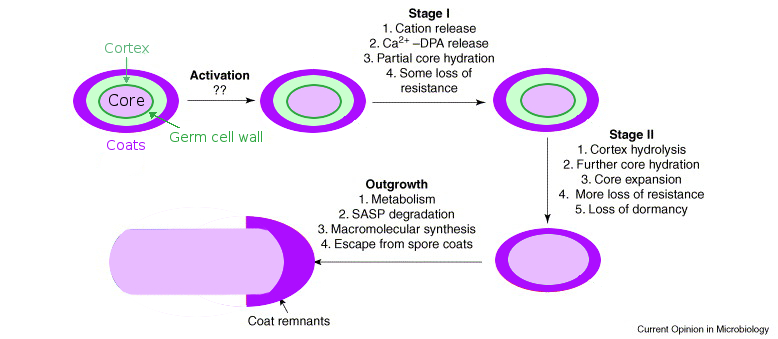

On its inner spore membrane, the spore has germinant receptors. The spore coats are believed to be semipermeable or porous, in order to permit the passage of germinants to the receptors. When germinants such as amino acids and sugars reach germinant receptors, the spore begins a biochemical process of germination. It takes up water, shifts its pH, and swells. It breaks out of its coat and begins the outgrowth process (see Fig. 2). We wish to prevent the germination process.

|

How do Germination Gene Knockouts Work?

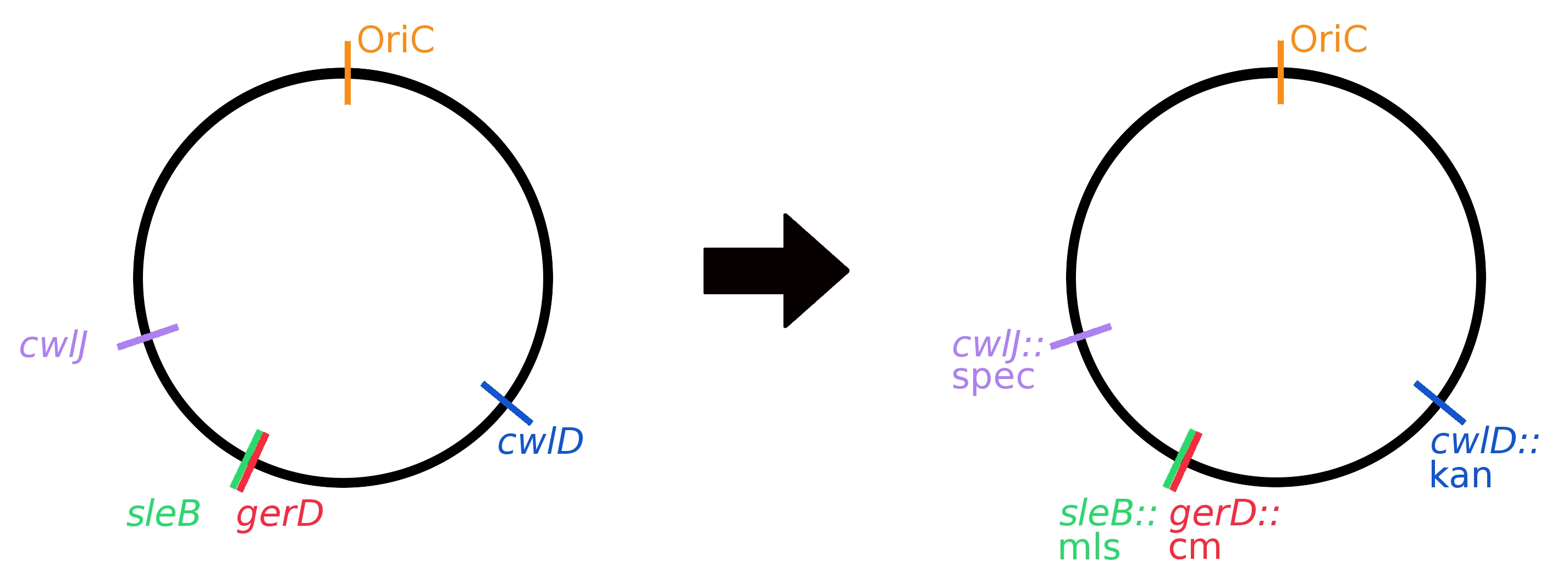

Based on the work of others, we chose to knock out genes cwlJ, sleB, cwlB, gerD, and cwlD. Past works showed:

- cwlJ and sleB: both genes code for lytic enzymes which are active in the process of germination. When knocked out together, germination frequency was reduced by 5 orders of magnitude.

- gerD and cwlB: the gerD product plays unknown role in nutrient germination; cwlB's product plays role in cell wall turnover & cell lysis. When knocked out together, germination frequency was reduced by 5 orders of magnitude.

- cwlD: this gene codes for recognition components for cleavage by the germination-specific cortex lytic enzymes. When knocked out, germination occurred at a rate of 0.003 to 0.05%.

By knocking out all five of these genes, our goal was to yield a B. subtilis strain which produces spores completely incapable of germination. The stop to germination comes during the process of spore coat breakdown. Without the lytic enzymes to break down the coat, the spores should be unable to outgrow into the vegetative stage. After several attempts to knock out cwlB, and producing extremely slow-growing mutants, cwlB was removed from our list of genes to knock out.

| Germination Genes | Gene Function | Mutant Germination Rate |

|---|---|---|

| gerD | Unknown role in nutrition germination | Reduction by 5 orders of magnitude |

| cwlJ | Germination-specific lytic enzymes | 0.003 – 0.05%

No ATP detected |

| sleB | Germination-specific lytic enzymes | 0.003 – 0.05%

No ATP detected |

| cwlD | Recognition component for lytic enzymes | 0.003 – 0-005% |

What Methods Did We Use to Knockout Germination Genes?

Two methods were employed to knock out germination: resistance cassette knockouts and clean deletions. Resistance cassette (RC) knockouts were performed using long-flanking-homology PCR (see Fig. 3 and Protocols). Single RC knockouts were created first; then they were combined to create multiple knockouts. The genome with all RC knockouts can be seen in Fig 4.

|

|

The germination rate of our mutants were checked with a germination assay. The assay was developed based on the protocols of other researchers. In the event that some small percentage of spores retained the ability to germinate, the Suicide switch subproject (below) prevents outgrowth into viable vegetative cells.

Suicide switch

|

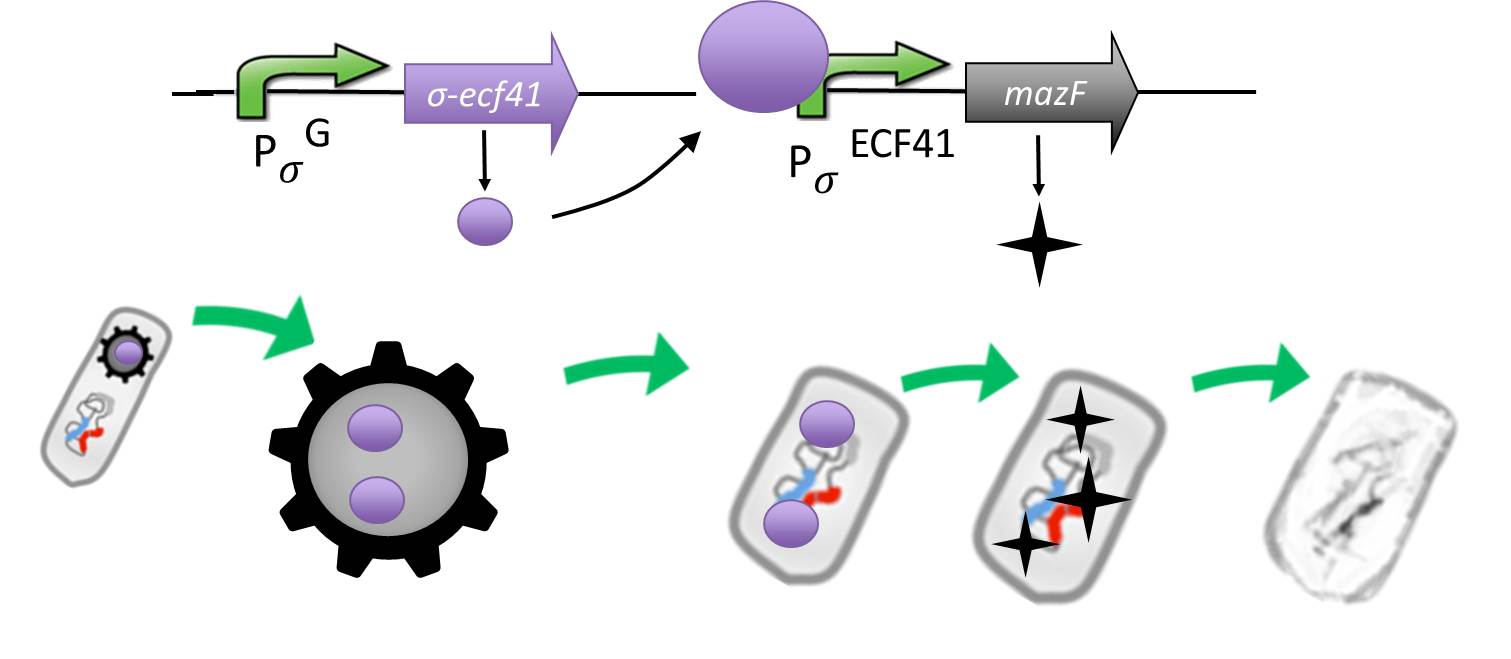

As a backup plan to make our Sporobeads even safer, we developed the Suicideswitch. In case the spores do germinate, due to degradation or destruction of their outer coats, e.g. by high pressure, the Suicideswitch will be turned on.

It is composed by an alternative sigma factor [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K823043 ECF41] ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3426412/ Wecke T., Mascher T. 2012]), which derives from B. lincheniformes and we chose to work with the short version constitutively on. It is synthetically linked to a sigma G regulated promotor responding quite late to sigma G ([http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K823048 PspoIVB] ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15699190 Steil L., Völker U. et al. 2005]) responding strongly or [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K823042 PsspK] ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15699190 Steil L., Völker U. et al. 2005]) responding weakly) which is the last sigma factor activated in the forespore. Through this ecf41 is produced quite late in the forespore. Ecf41 then activates the [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K823041 PydfG] ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3426412/ Wecke T., Mascher T. 2012]) promotor, which is the naturally responding promoter to ECF41, which then activates the transcription of [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K823044 MazF] ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15699190 Engelberg-Kulka H.,Amitai S. 2005]), a bacterial toxin from E.coli degrading mRNA.

The idea behind this is to pack the Sporobeads full with ECF41 when they sporulate, which will in turn kill them upon germination due to the MazF.

Through the system with the alternative sigma factor the forespore gains hopefully enough time to fully mature before MazF starts to be produced.

We chose MazF, as we think it will not be able to harm our Sporobead even if it is made too early, as the spore does not rely on translation to be preserved.

See what Data we get when measuring a module with luxABCDE instead of MazF.

We are planning to model this system, but still need some Data for it, including such which are first possible to get after cloning PsspK and MazF.

|

|

|

|

| Bacillus Intro | Bacillus BioBrickBox | Sporobeads | Germination STOP |

"

"