Team:Potsdam Bioware/Project/Part AID

From 2012.igem.org

(→Discussion) |

(→Intracellular localization of the modified AID) |

||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

===== ''Intracellular localization of the modified AID'' ===== | ===== ''Intracellular localization of the modified AID'' ===== | ||

| - | With fluorescence microscopy we detected the eGFP fluorescence of the modified AID-eGFP fusion protein. In the following pictures we can see that the modified AID is actively transported into the nucleus where we see a great eGFP fluorescence. That means the NLS is functional and able to recruit the factors necessary for import into the nucleus. | + | With fluorescence microscopy we detected the eGFP fluorescence of the modified AID-eGFP fusion protein. In the following pictures we can see that the modified AID is actively transported into the nucleus where we see a great eGFP fluorescence. That means the NLS is functional and able to recruit the factors necessary for import into the nucleus.<br> |

| + | <br> | ||

| + | [[file:UP_12_intracellulare_location.png|center|300px|thumb|Fig. 3: Intracellulare location of modified AID with eGFP]] | ||

===== ''Comparison of mutation rates of modified and wildtype AID'' ===== | ===== ''Comparison of mutation rates of modified and wildtype AID'' ===== | ||

Revision as of 10:21, 26 September 2012

Mutation Module

Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID)

Contents |

Introduction

The activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) is one of the key enzymes of mammalian immune system and a central controlling point for the somatic hypermutation (SHM)(Muramatsu et al. (2000), Revy et al. (2000)), class switch recombination (Muramatsu et al. (2000)) and gene conversion (Arakawa et al. (2002), Harris et al. (2002)) (fig. 1). The AID is expressed in B-lymphocytes and active during B-lymphocyte activation. Because of sequence similarities to APOBEC (apolipoprotein B messenger RNA-editing enzyme catalytic polypetide) enzymes many functional and structural aspects of the AID were postulated (Prochnow et al. 2007). Today we know that the AID catalysis the deamination of cytidine to uracil on the DNA level. A deficiency of AID or mutations within the coding sequence causes a defect of antibody maturation, class switch recombination and gene conversion.

Structure of the AID

The AID is a 28 kDa small protein with a highly conserved structure. The three-dimensional structure was not clear up until today. But because of structural homologies to the APOBEC enzymes some structural aspects were suggested (Prochnow et al. (2007)) (fig. 2). However, it is known that the AID has a non-functional N-terminal nuclear location sequence (NLS) and a C-terminal nuclear export sequence (NES). In the middle of the primary sequence the cytidine motif and the APOBEC-like motif is localized (fig. 3). Because of simulations it was suggested that the AID is a dimer and every subunit binds to the DNA.

Substrate specificity of the AID

It was shown that the AID mutates DNA instead of RNA in case of APOBEC enzymes. The substrate of the AID is the singlestranded DNA. Therefore a correlation between the mutation rate and the transcription rate existed which means that the greater the transcription activity the higher the mutation rate. That’s the reason why the AID has to be localized in the nucleus of eukaryotic cells to mutate the DNA sequence. Because of the NES the enzyme is actively exported. Nevertheless the small size of the AID allows it to diffuse through the nuclear pore complexes into the nucleus. The SHM should take place on the variable regions (V-regions) of the antibodies; the binding sites to the antigen. Therefore the AID should bind specific to the V-regions and catalysis the mutation. However, the SHM was also observed in the genes bcl-6 and FasL albeit with a much lower mutation rate (Pasqualucci et al. (1998, 2001), Shen et al. (1998), Muschen et al. (2000)). Consequnetly, it was suggested that the AID has no direct substrate specificity and maybe interact with some cis acting factors to ensure a significantly greater mutation rate in the V-regions than in other genes. After sequence analysis of the mutated target sequences is was found out that the AID mutates predominantly small sequence motifs; so called hotspots.

AID as a key component of the Antibody generating system

In a prior publication it was shown that the AID can be used to maturate antibody sequences to produce high affine binding molecules in CHO cells. In our project we also use the AID to mutate the antibody sequences in CHO cells. Therefore we cloned the AID biobrick (BBa_K103001) with the CMV promoter and the hGH-polyA tail together to transfect transiently the CHO cells. We expected that the mutation rate is depending on the predominantly location of this enzyme in the cell. Therefore we concluded that the mutation rate increase with the increasing resting time of the AID in the nucleus. Therefore we knocked out the C-terminal NES and add a functional NLS to the N-terminus to ensure a greater resting time in the nucleus. To investigate whether the modifications are functional we fused the modified AID with the eGFP.

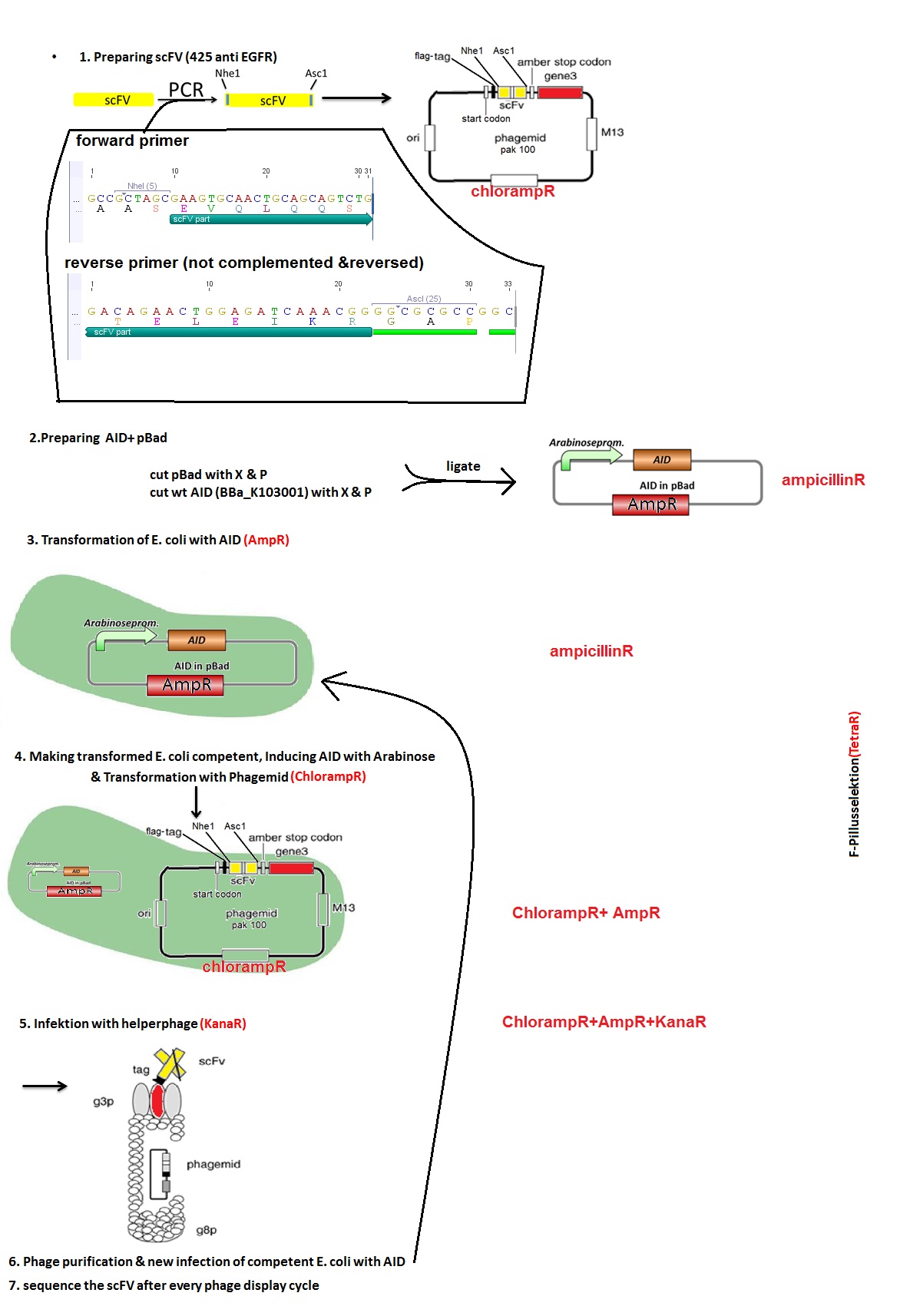

Testing AID mutation rate in E.coli with phage display

In order to characterize the AID and its potential to mutate antibody fragments, phage display is used. This powerful selection tool tests for proteins or peptides from a large recombinant library with specific binding abilities for a defined target. A gene of interest is introduced into the bacteriophage genome and is presented on the surface of the phage allowing the selection for the phenotype closely coupled to the genotype.

We transformed simultaneously E.coli cells (strain ER2738) with an arabinose inducible AID enzyme and a single chain antibody fragment EGFR-C on the phagemid vector pAK100. By allowing the enzyme to mutate the antibody fragment over a certain time we are generating a diverse library of antibody sequences. After the infection of E.coli cells with the helper phage, bacteriophages are produced and the mutated antibody sequence is randomly incorporated into their genome. Subsequently, E.coli cells were infected with the phages containing mutated antibody fragments. To observe the mutation rate of the antibody fragment, after three cycles of infection and phage production in presence of AID, multiple phagemids were sequenced.

Results

Cloning of the wildtype, modified AID and modified AID fused with eGFP

For cloning the composite part wildtype AID (wt AID) we used the biobrick BBa_K103001. To ensure the expression in eukaryotic cells we cloned the wt AID together with the CMV promoter and the polyA tail from the hGH gene.

The modified AID was amplified with primers which contains the Kozak sequence and the NLS, and which relieve the present NES in the sequence. The Kozak sequence ensures a greater expression combined with the CMV promoter than the CMV promoter alone. The NLS cater for the import into the nucleus supported by the knock out of the NES. For detecting the expression of the modified AID we fused this protein with eGFP.

To detect the expression we measured the fluorescence time depending after transfection in CHO cells for computing the expression rates.

Intracellular localization of the modified AID

With fluorescence microscopy we detected the eGFP fluorescence of the modified AID-eGFP fusion protein. In the following pictures we can see that the modified AID is actively transported into the nucleus where we see a great eGFP fluorescence. That means the NLS is functional and able to recruit the factors necessary for import into the nucleus.

Comparison of mutation rates of modified and wildtype AID

For detecting the mutation sites and rates of the wt AID and the modified AID, we developed two approaches to detect mutation in a certain query sequence. First of all, we transfected the CHO cells with the single chain construct and the AID variant. After certain expression time we purified the cotransfected plasmids for the single chain construct for the first approach and transformed them into E.coli to enrich the mutations. After overnight culture and purification of the transformed plasmids we send the samples for sequencing. For the second approach, we sorted the cells transfected with the modified AID-eGFP construct and the single chain YFP construct by FACS. These cells were lysed and the plasmids with the single chain purified. After that, the purified single chain constructs were transformed into E. coli to enrich the mutations.

In fig. 4, we can see that there is a significant higher mutation rate with the wildtype AID, modified AID and modified AID-eGFP in comparison without AID. Surprisingly, the mutation rate of wt AID is two times higher than the mutation rate of the modified AID or modified AID-eGFP. This observation is contrary to our expectation. One possible explanation is that the modified AID has a very high mutation rate and therefore the transfected cells die or inactivate the plasmid like it was observed for the wildtype AID (Martin and Scharff (2002)).

Mutation rate in E.coli measured via Phage display

The expected mutations did not occur, so we started wondering what could be the reason for that. We decided to check if the expression of AID occurs after addition of arabinose. We took samples after 3 and 5 hours. There were no bands on the gel so we had no AID expression even though theoretically AID is placed behind the arabinose inducible promoter. We think the reason could be the 11bp long distance between RBS and start codon instead of the regular 7bp in the designed pBAD vector with AID. The experiments should therefore be repeated, starting from vector design.

How did we do that?

Figure 5 describes the subsequent steps: we first created two vectors: pAK100 with scFV - phagemid via PCR (Point 1) and pBAD with AID (Point 2). Then, we transformed the E.coli ER2738 strain with both of them (Point 3 and 4). Afterwards, we added the helper phages (VSCM13) and let them infect the cells. The culture was then streaked on an agar plate with proper antibiotica and the positive clones were sent for sequencing. Simultaneously, the phages were purified. For the subsequent rounds of phage display we collected all of the colonies grown on the plate and used them for overnight culture landing again in point 3. Also instead of helper phages, the purified phages from previous round were used for infection.

Discussion

Cloning of wt AID, modified AID and modified AID with eGFP

The sequencing results showed that the cloning of wt AID, modified AID and modified AID with eGFP was successful without any mutation in the coding sequence.

Comparison of the mutation rates of wt AID and modified AID in connection with the intracellular localization

Like it was mentioned in the result part of the mutation module, there is a difference between the mutation rates of wt AID and modified AID. The wt AID has a two times higher mutation rate than the modified AID. We expected that this observation is vice versa. There are three possible explanations for this behavior which are based on the observation that there is a very high among of modified AID in the nucleus because of the NLS and the knocked out NES, as we can see in the fluorescence picture. This means a high concentration of a mutagenic enzyme which mutates unspecifically single stranded DNA. In contrast, the wt AID is actively transported out of the nucleus because of the NES.

One possible explanation is that these cells which contain a functional modified AID died and cannot be observed anymore.

The second possibility is that because of the high mutation rate the modified AID is inactivated by transfected cells like it was observed for wt AID transfected CHO cells.

And the last explanation can be that these cells which lost the DNA for the modified AID have a selection advantage and therefore grow predominantly.

We did not expect that the modified AID is disfunctional because of mutation or any folding interfering sequences like the NLS or NES because, firstly, the sequencing results show no mutation in the coding, promoter or terminator region of the modified AID. And secondly, we even observed a two times higher mutation rate in comparison to the control cells which are not transfected with AID or modified AID even after one day incubation. In prior publications, the incubation of the AID with selection marker for eukaryotic cells takes much longer to see any mutations.

Materials and Methods

References

- Muramatsu M, Kinoshita K, Fagarasan S, Yamada S, Shinkai Y, Honjo T. Class switch recombination and hypermutation require activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a potential RNA editing enzyme. Cell. 2000 Sep 1;102(5):553-63. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=Muramatsu%2C%20M.%2C%20Kinoshita%2C%20K.%2C%20Fagarasan%2C%20S.%2C%20Yamada%2C%20S.%2C%20Shinkai%2C%20Y.%26Honjo%2C PubMed PMID: 11007474.]

- Revy P, Muto T, Levy Y, Geissmann F, Plebani A, Sanal O, Catalan N, Forveille M, Dufourcq-Labelouse R, Gennery A, Tezcan I, Ersoy F, Kayserili H, Ugazio AG, Brousse N, Muramatsu M, Notarangelo LD, Kinoshita K, Honjo T, Fischer A, Durandy A. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) deficiency causes the autosomal recessive form of the Hyper-IgM syndrome (HIGM2). Cell. 2000 Sep 1;102(5):565-75. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=Revy%2C%20P.%2C%20Muto%2C%20T.%2C%20Levy%2C%20Y.%2C%20Geissmann%2C%20F.%2C%20Plebani%2C%20A.%2C%20Sanal%2C%20O.%2C%20Catalan%2C PubMed PMID: 11007475.]

- Arakawa H, Hauschild J, Buerstedde JM. Requirement of the activation-induced deaminase (AID) gene for immunoglobulin gene conversion. Science. 2002 Feb 15;295(5558):1301-6. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=Arakawa%2C%20H.%2C%20Hauschild%2C%20J.%20%26%20Buerstedde%2C%20J.%20M.%20(2002)%20Science%20295%2C%201301%E2%80%931306. PubMed PMID: 11847344.]

- Harris RS, Sale JE, Petersen-Mahrt SK, Neuberger MS. AID is essential for immunoglobulin V gene conversion in a cultured B cell line. Curr Biol. 2002 Mar 5;12(5):435-8. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=Harris%2C%20R.%20S.%2C%20Sale%2C%20J.%20E.%2C%20Petersen-Mahrt%2C%20S.%20K.%20%26%20Neuberger%2C%20M.%20S.%20(2002)%20Curr. PubMed PMID: 11882297.]

- Prochnow C, Bransteitter R, Klein MG, Goodman MF, Chen XS. The APOBEC-2 crystal structure and functional implications for the deaminase AID. Nature. 2007 Jan 25;445(7126):447-51. Epub 2006 Dec 24. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17187054 PubMed PMID: 17187054.]

- Vallur AC, Yabuki M, Larson ED, Maizels N. AID in antibody perfection. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007 Mar;64(5):555-65. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17262167 Pubmed PMID: 17262167]

- Pasqualucci L, Migliazza A, Fracchiolla N, William C, Neri A, Baldini L, Chaganti RS, Klein U, Küppers R, Rajewsky K, Dalla-Favera R. BCL-6 mutations in normal germinal center B cells: evidence of somatic hypermutation acting outside Ig loci. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998 Sep 29;95(20):11816-21. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=Pasqualucci%2C%20L.%2C%20Migliazza%2C%20A.%2C%20Fracchiolla%2C%20N.%2C%20William%2C%20C.%2C%20Neri%2C%20A.%2C%20Baldini%2C PubMed PMID: 9751748;]

- Pasqualucci L, Neumeister P, Goossens T, Nanjangud G, Chaganti RS, Küppers R, Dalla-Favera R. Hypermutation of multiple proto-oncogenes in B-cell diffuse large-cell lymphomas. Nature. 2001 Jul 19;412(6844):341-6 [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=Pasqualucci%2C%20L.%2C%20Neumeister%2C%20P.%2C%20Goossens%2C%20T.%2C%20Nanjangud%2C%20G.%2C%20Chaganti%2C%20R.%20S.%2C PubMed PMID: 11460166.]

- Shen HM, Peters A, Baron B, Zhu X, Storb U. Mutation of BCL-6 gene in normal B cells by the process of somatic hypermutation of Ig genes. Science. 1998 Jun 12;280(5370):1750-2. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=Shen%2C%20H.%20M.%2C%20Peters%2C%20A.%2C%20Baron%2C%20B.%2C%20Zhu%2C%20X.%20%26%20Storb%2C%20U.%20(1998)%20Science%20280%2C PubMed PMID: 9624052.]

- Müschen M, Re D, Jungnickel B, Diehl V, Rajewsky K, Küppers R. Somatic mutation of the CD95 gene in human B cells as a side-effect of the germinal center reaction. J Exp Med. 2000 Dec 18;192(12):1833-40. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11120779 PubMed PMID: 11120779.]

- Martin A, Scharff MD. Somatic hypermutation of the AID transgene in B and non-B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002 Sep 17;99(19):12304-8. Epub 2002 Aug 29. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=Somatic%20hypermutation%20of%20the%20AID%20transgene%20in%20B%20and PubMed PMID: 12202747.]

"

"