Team:UNITN-Trento/Project/Terminators

From 2012.igem.org

Terminator 5

INTRODUCTION

Transcriptional termination is an essential process in biology, but its characterization and investigation have always been underestimated, if compared with other mechanisms as transcriptional promotion. This underestimation is further sharpened by the difficulties in efficiently characterize terminators. Also in the Registry of Standard Parts many terminators are not fully characterized and don’t present reliable data because of the big standard deviations affecting the results.

This work concerns various aspects of the transcriptional termination process and the characterization of transcriptional terminators:

we improved a very common strategy to characterize terminators, that is the usage of a bicistronic message of fluorescent proteins in which terminators can be inserted. This allows the evaluation of terminators effect on protein expression as ratiometric and fluorimetric measurements.

we tested this system on two terminators commonly used in synthetic biology: the T7 transcriptional terminator from the vector pET21a and the E. coli strong transcriptional terminator (T1 rrnB). The results obtained represent a new characterization of these terminators (that were also confirmed by sequencing and submitted in the Registry under the names BBa_K731721 and BBa_K731722, respectively).

we investigated the effect of different polymerases on the termination efficiencies of the two terminators tested. The investigation of this possible relation is a quite new approach; we decided to begin with the characterization of terminators using the standard tacI promoter, which is well recognized by sigma–70 E. coli RNA polymerase (RNAP) and the the most common T7 promoter recognized by the T7 RNAP.

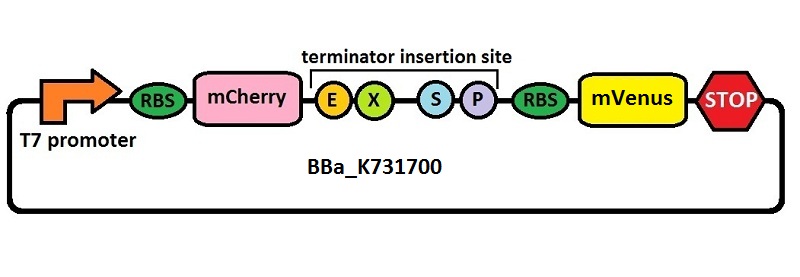

These BioBrick compatible plasmid backbones used as platforms were deposited under the names BBa_K731700 and BBa_K731710.

Ideally, transcriptional termination efficiencies would be measured by directly quantifying truncated and full length transcripts. In practice, due to the difficulties in accurately determining in vivo RNA levels, fluorescence deriving from messages encoding fluorescent proteins are used as a proxy for RNA levels. We are aware that protein levels are not the same as transcript concentrations. Nevertheless, protein concentrations typically are related to RNA concentrations, and fluorescent protein measurements are much more amenable to high-throughput technologies. Additionally, as the final goal is often times the control of protein ratios, such fluorescent protein based assays directly evaluates the influence of RNA elements on protein expression levels.

We hope this work will be helpful for the future characterization of terminators and to increase the available possibilities in synthetic biology. Moreover, we hope that it will be a good starting point to further investigate transcriptional termination and the factors that could affect it.

OUR METHOD

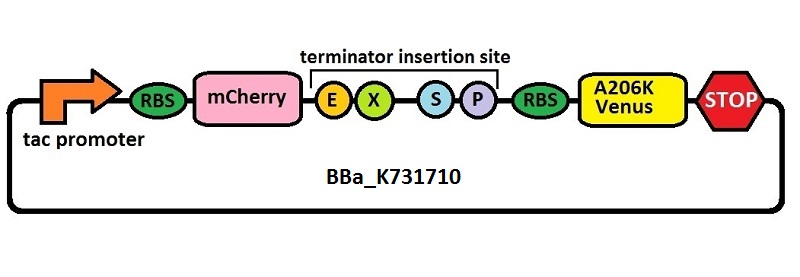

The first thing we did was to build a platform from which we could measure transcriptional termination efficiencies through fluorescence. We started with a previously constructed plasmid backbone (RL024A) from the Mansy lab that was built by Roberta Lentini. RL024A is essentially pET21b with the genes encoding the fluorescent proteins mCherry and A206K Venus (mVenus) separated by a 20 bp linker inserted into the polyclonal region. pET21b contains a T7 transcriptional promoter. RL024A and the parent plasmid pET21b also contain three illegal sites, which had to be removed. Finally, the prefix-suffix sequence was inserted between the mCherry and mVenus genes in order to give rise to our first construct, BBa_K731700. In summary, BBa_K731700 is a plasmid backbone with a T7 transcriptional promoter in which transcriptional terminators can be inserted in between genes coding for mCherry and mVenus through standard BioBrick assembly.

The first thing we did was to build a platform from which we could measure transcriptional termination efficiencies through fluorescence. We started with a previously constructed plasmid backbone (RL024A) from the Mansy lab that was built by Roberta Lentini. RL024A is essentially pET21b with the genes encoding the fluorescent proteins mCherry and A206K Venus (mVenus) separated by a 20 bp linker inserted into the polyclonal region. pET21b contains a T7 transcriptional promoter. RL024A and the parent plasmid pET21b also contain three illegal sites, which had to be removed. Finally, the prefix-suffix sequence was inserted between the mCherry and mVenus genes in order to give rise to our first construct, BBa_K731700. In summary, BBa_K731700 is a plasmid backbone with a T7 transcriptional promoter in which transcriptional terminators can be inserted in between genes coding for mCherry and mVenus through standard BioBrick assembly.

Subsequently, an analogous system with an E. coli transcriptional promoter in place of the T7 promoter was constructed. More specifically, a type of insertion-deletion PCR was used to insert an E. coli tacI transcriptional promoter and remove the T7 promoter (BBa_J64997). This plasmid backbone is hereafter referred to as BBa_K731710.

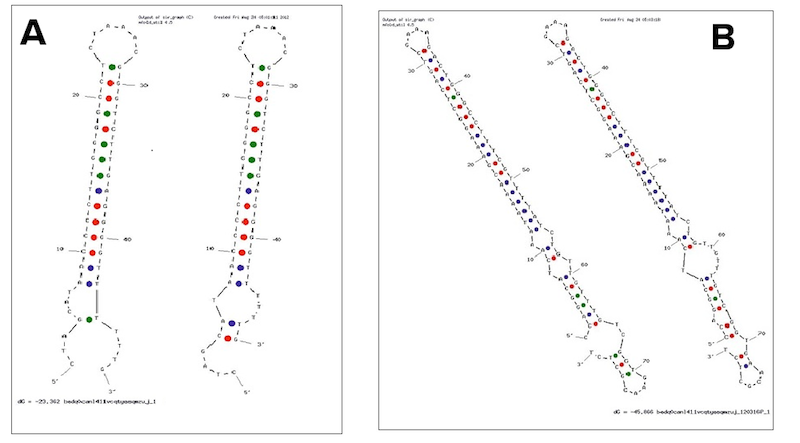

Examples of secondary structures assumed by the T7 terminator (A) and the E. coli (B) terminator tested.

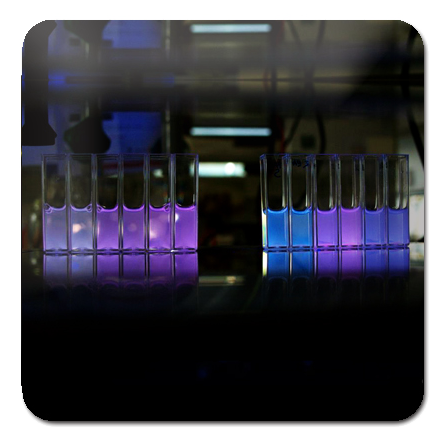

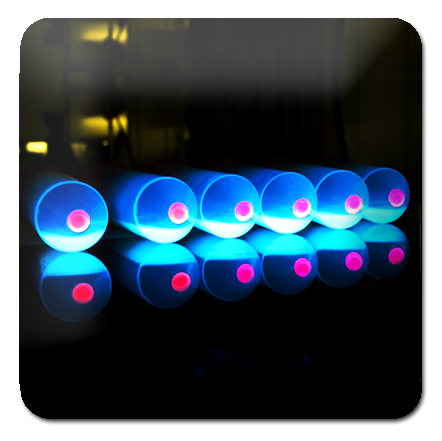

We firstly measured the empty platforms to define the best usage protocol that allows precise results. We exploited a Varian Cary Eclipse Fluorescence Spectrophotometer and an E. coli lysogen strain carrying T7 RNA polymerase and lacIq. Additionally, the cells, i.e. E. coli BL21(DE3) pLysS, also contained a plasmid encoding T7 lysozyme and chloramphenicol resistance. T7 lysozyme is a natural inhibitor of T7 RNA polymerase activity, thus reducing background expression of the target genes. The T7 RNA polymerase is a behind a lacUV5 promoter.

We made several experiments to asses the best conditions to take measurements, more specifically we tested the excitation wavelengths, the inducing agent concentration, two different treatments of the colonies and the incubation time. To determine if our results were reliable we also measured colonies from different transformation plates and in a wide time-range.

We used the protocol as defined above to characterize the two terminators.

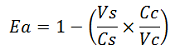

The apparent termination efficiency (Ea) was calculated using the following equation:

Where Vs is the intensity of mVenus when behind the terminator of interest, Vc is the intensity of mVenus in the absence of a preceding terminator (that is, the control), Cs is the intensity of mCherry when followed by the terminator of interest intensity, and Cc is the intensity of mCherry in the absence of the terminator of interest, i.e. the control.

RESULTS

The first step toward a good characterization in terms of statistics, reliability, repeatability and feasibility was to develop a protocol that fulfills each one of these points. Exploring a large window of different parameters and validating the data collected through statistic analysis we obtained a good and easy protocol for transcriptional terminators characterization in vivo, that gave ratiometric results affected by an acceptable standard deviation (as shown in the terminators characterization charts below). Theoretically, this protocol should work for any platform that exploits a bicistronic message encoding two fluorescent proteins (of course it would have to be tested on them and some minor changes could be necessary). Its fundamental points are probably the maintaining of the same optical density between the samples during induction, the sonication of the samples and the incubation over-night that allows fluorescence stabilization. The protocol and further details can be found here.

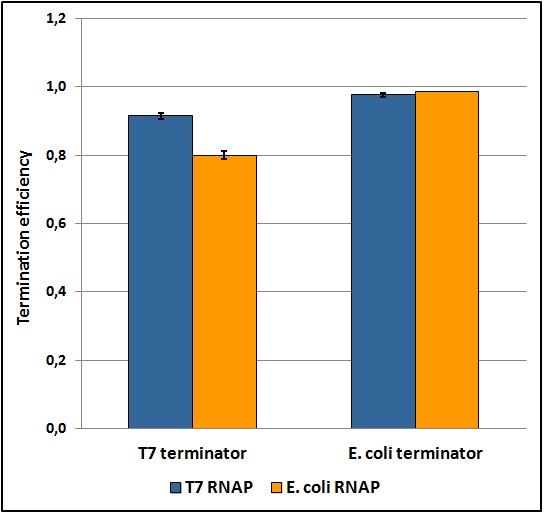

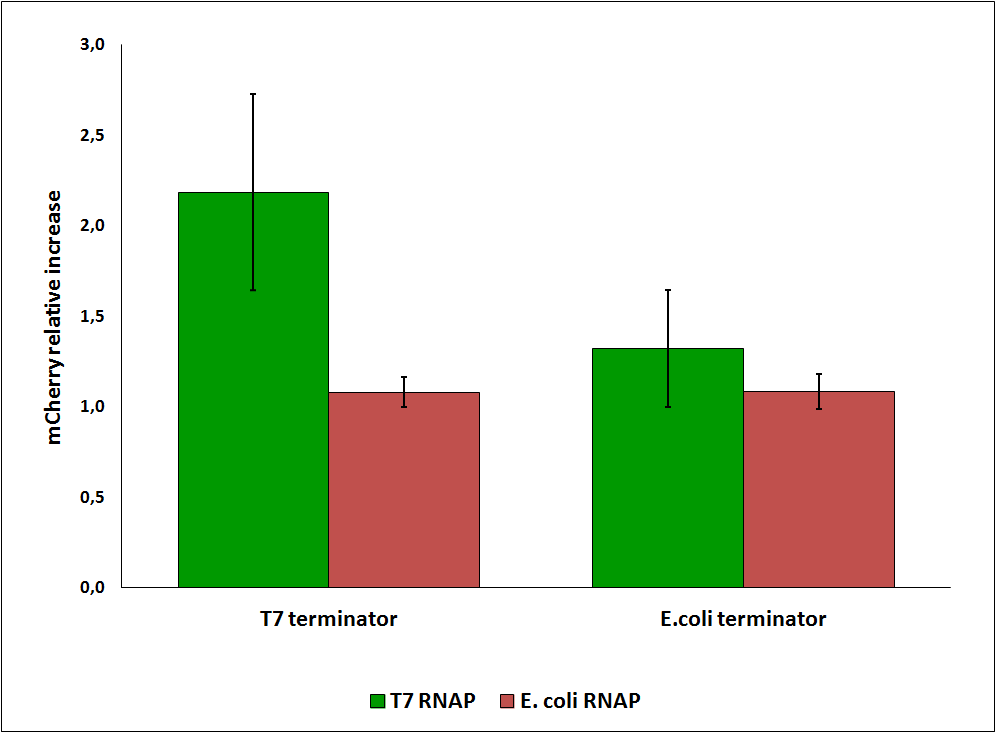

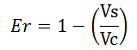

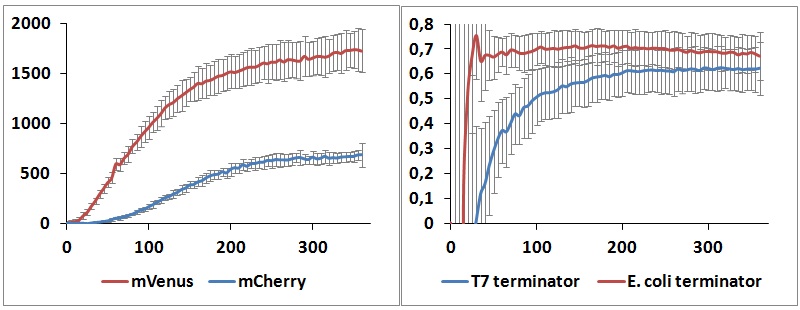

Figure 5: Transcriptional termination efficiencies of T7 and E. coli terminators with T7 and E. coli RNA polymerases (RNAP).

While collecting the above data, we noticed that the raw fluorescence intensities for mCherry seemed to increase in the presence of the T7 transcriptional terminator when using the T7 RNA polymerase. This effect was previously described for some terminators by H. Abe and H. Aiba [1]. To further explore this potential influence, we had to compare different cultures, with and without intervening terminator in the transformed plasmid. Thus, we repeated the experiment ensuring that all measurements were taken from cultures that were induced at the same optical density (O.D.), more information can be found here. The mCherry fluorescence was then analyzed with the following equation, that represent the Relative Increase in the upstream gene expression, where Cs is the intensity of mCherry when followed by the terminator of interest, and Cc is the intensity of mCherry of the control construct that did not contain the terminator.

Figure 6: Relative increase in upstream gene expression of constructs with T7 and E. coli terminators, T7 and E. coli RNA polymerases (RNAP).

Since the apparent transcriptional termination efficiencies were calculated as a ratio of mVenus over mCherry levels, an increase in mCherry fluorescence would result in an over estimation of the termination efficiency. To investigate whether our values were, indeed, over estimated, we calculated raw termination efficiencies from the same samples used for the mCherry measurements. The fluorescence intensities of mVenus were evaluated without considering mCherry emissions with the following equation:

When the contribution of mCherry was removed, the data suggested that the RNA polymerase did not influence the transcriptional termination efficiency (Figure 7).

Figure 7: The raw and apparent termination efficiencies of T7 and E. coli terminators with T7 and E. coli RNA polymerases.

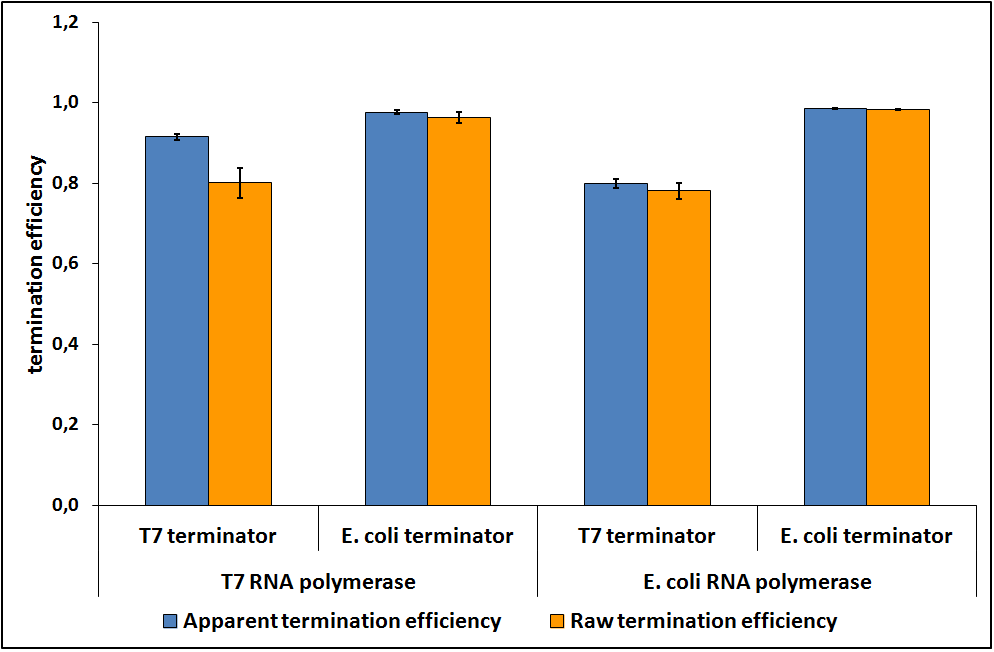

One potential reason for the increased mCherry levels could be that the terminator protects the transcript from the activity of cellular RNases. Although RNases would not explain why the effect was only observed for the T7 promoter - T7 terminator combination, we decided to test some of the constructs in a purified system that lacked the presence of nucleases. Therefore, we exploited the PURExpress kit from New England BioLabs, which consists of purified transcription - translation machinery, including T7 RNA polymerase and E. coli ribosomes. First, the data showed that the transcriptional termination efficiencies, both apparent and raw, were significantly lower in the purified, in vitro system for both T7 and E. coli terminators than the data obtained from the in vivo experiments (Figure 8). This is consistent with the fact that T7 lysozyme, which was not present in our in vitro experiments but was present in vivo, aids in transcriptional termination [2]. Second, the stabilization effect was significantly diminished in vitro, suggesting that RNases or other unidentified cellular factors were involved. Some kinetic profiles of the reaction can be found below (Figure 9).

Figure 8: The activity of T7 and E. coli terminators in vitro with purified T7 RNA polymerase and E. coli translation machinery. Left, right and bottom panels show apparent termination efficiencies, raw termination efficiencies, and normalized mCherry expression.

Figure 9: in vitro kinetics measurements. Left panel shows the raw emission peaks intensities obtained with T7 RNA polymerase and T7 terminator. Right panel shows the raw termination efficiencies of both terminators with the same platform.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

In the future, some experiments are necessary to further explore the influences that various factors could have on termination efficiencies. Firstly, the investigation of the effect of T7 lysozyme would be informative and perhaps could provide for an additional platform to control protein ratios. For example, the suppression of one protein could be achieved by simply inducing the expression of T7 lysozyme.

Additionally, the apparent stabilization effect resulting in increased mCherry levels in the presence of the T7 terminator should be explored. If the result proves to be real, then such influences would need to be accounted for when exploiting transcriptional terminators to modulate protein levels arising from polycistronic messages.

The main aims of this project were to develop an easy protocol for the characterization of transcriptional terminators and to propose a new line of study in this field (the interchangeability of the parts between organisms). Therefore, we hope that this protocol will improve the amount of the available fully-characterized and ready-to-use terminators and that this new investigation approach will be carried on by others in the future.

We believe that a deeper knowledge of transcriptional terminators and a precise analysis of their efficiencies can introduce the development of polycistronic expression vectors with predetermined ratio between proteins (for example a single bicistronic construct coding for both CysE and CysDes). This would greatly increase the available possibilities in synthetic biology and could maybe replace other methods to obtain and control proteins production.

REFERENCES:

- Abe H and Aiba H. Differential contributions of two elements of rho-independent terminator to transcription termination and mRNA stabilization. Biochimie 1996; 78(11-12) 1035-42.

- Lyakhov DL, He B, Zhang X, Studier FW, Dunn JJ, McAllister WT, Pausing and termination by bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. J. Mol. Biol. 1998; 280(2): 201–13.

"

"